Morocco’s Gnawa Music Festival is a melee of dreadlocks and drumbeats. Lots of hash and condoms, too.

It’s late afternoon on the Atlantic Coast and a lazy wind is rolling in, weaving between surfboards and mint tea. I’m with a group of new friends in a café in Essaouira, Morocco. We’re all here for a unique world music festival, and I’m trying to figure out if this heady beach party is by Moroccans for Moroccans, or if it’s a watered-down experience Westernized enough for foreigners with deep pockets.

“It’s definitely for foreigners,” Walid, a twenty year-old student, tells me. It’s his second time attending the Gnawa Music Festival, this time with a group of dreaded friends in tow, all from the capital city of Rabat.

“Really?” I ask, slightly incredulous.

“Definitely,” they repeat.

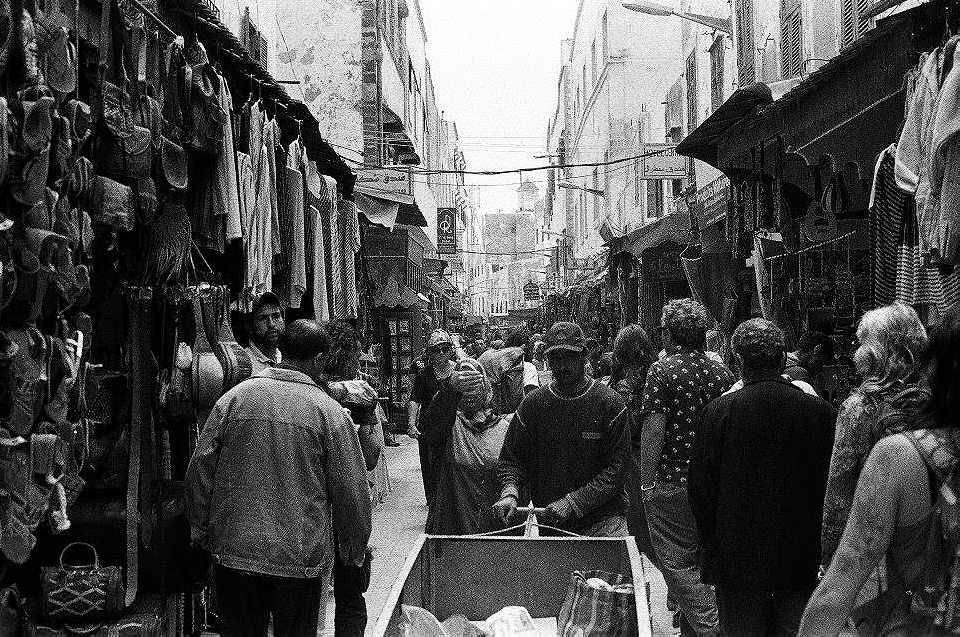

Held annually since 1997 in this sun-bleached coastal town, Gnawa hosts international acts in jazz, hip-hop, blues, and soul, but it is intended primarily as a meditation on preserving traditional Gnawan music based on African and Islamic traditions. The festival has grown from a small-scale series of concerts for Moroccans (particularly Essaouirians) and some incredibly in-the-know music fans. In recent years, it has attracted an increasingly diverse and international crowd: young backpackers looking for hash and a free show, older European couples excited for an immersive cultural experience, politicos in suits, and what seems like Morocco’s entire Rastafarian population.

Historically, the festival has been an expression of Moroccan and West African music and dance. The focus is on African performers, and there’s a strong sense of African unity that would clearly exclude most white Europeans. “Si vous êtes d’accord, dit Afrique, c’est un,”—“If you agree, say Africa is one”—belts the Nigerian-German singer Ayo one night. But in Essaouira, a town where both Mick Jagger and Jimi Hendrix have put up their feet and pulled out their guitars, instances of cultural exchange and subsequent appropriation run deep in ways that aren’t altogether clear.

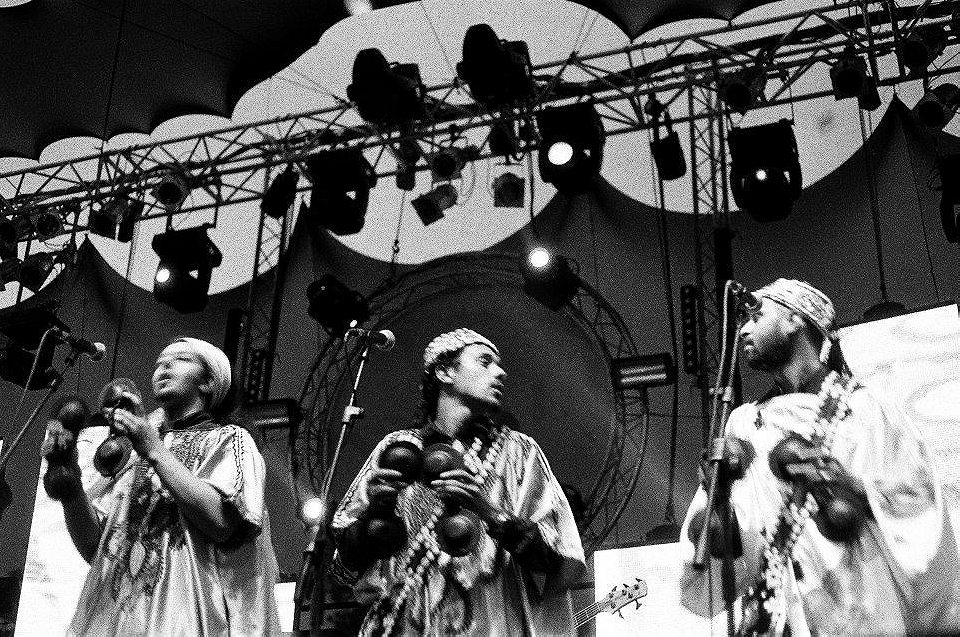

Traditionally, Gnawa music was performed in enclosed spaces to select groups of people. But the main stage, Place Moulay Hassan, is decidedly public, lending to the modernization of the music. “People aren’t necessarily going to understand the traditional,” fusion band Kif Samba’s drummer Yassin tells me before his headlining concert. “So to commercialize it, the sound has to be more international but at it’s core, it’s African music.” Indeed, most of the free, headlining acts are more fast-paced than traditional Gnawan music, and musicians are open to collaborations with foreign musicians. To see the “intimate” Gnawan performances, you can pay the several hundred dirham fee to attend a private, indoor concert.

The first night I head to Place Moulay Hassan for the opening concert. The square is jammed with people in every conceivable position; children have climbed up onto the metal barriers and are shaking their arms and torsos, legs tightly clamped down to secure their seating arrangement. The first show is a so-called fusion performance by Maâlem Hassan Boussou (respected Gnawan musicians are called maâlems) and fifty-eight year-old French jazz violinist Didier Lockwood, who boasts a seriously impressive full head of hair that shakes in time to the music.

Gnawa is a Berber word that refers to black slaves brought from Western Africa into Northern Africa from the 11th to the 13th century. It has historically been used as a color distinction to designate between and divide Moroccan ‘Africans’ and ‘Arabs.’ Over time, gnawa has evolved to refer to the musical fusion between West and North African music. The songs themselves are a blend of African tradition and Islamic spirituality. Chants are religious (the word Allah is a vocal bulwark of much of the repertoire) and the songs are rhythmic and upbeat.

The music is heavily instrumental, using qraqabs, heavy iron castanets the length of a man’s hand, and gimbri, three-stringed lutes. Maâlem Boussou’s band appeared on stage in a drum line procession, wearing cerulean blue tunics and fez-like hats. The drumbeats, which are solid and sit in the middle of my ribcage, drown out Mr. Lockwood’s enthusiastic violin playing. The music is joyful and trance-like: throughout the festival I see many people head-banging, their hair whipping wildly around their face.

The dancing incorporated into the music, a series of flying jumps and squats sustained for the entire performance, is equally impressive. It looks like a cross between Sufi-style whirling and a high-intensity aerobics class. My thighs hurt as I watch the performers, which include a graying grandfather holding onto a cane and swaying to the music, and a six year-old boy performing leaping splits (which elicits delighted screams from the crowd).

The concert lasts past midnight, before people head off to eat cheap kebabs and drink tea. Those with logistical common sense have booked hotels well in advance (the festival’s popularity has allowed enterprising hoteliers to jack up their prices astronomically); the rest sleep on the beach or stay up for their own private reverie. In the same vein as jazz festivals, the music only happens at night. “The first few years of the festival were better,” Brahim, 35, a shopkeeper tells me. “There was music everywhere, all the time. Now there isn’t.”

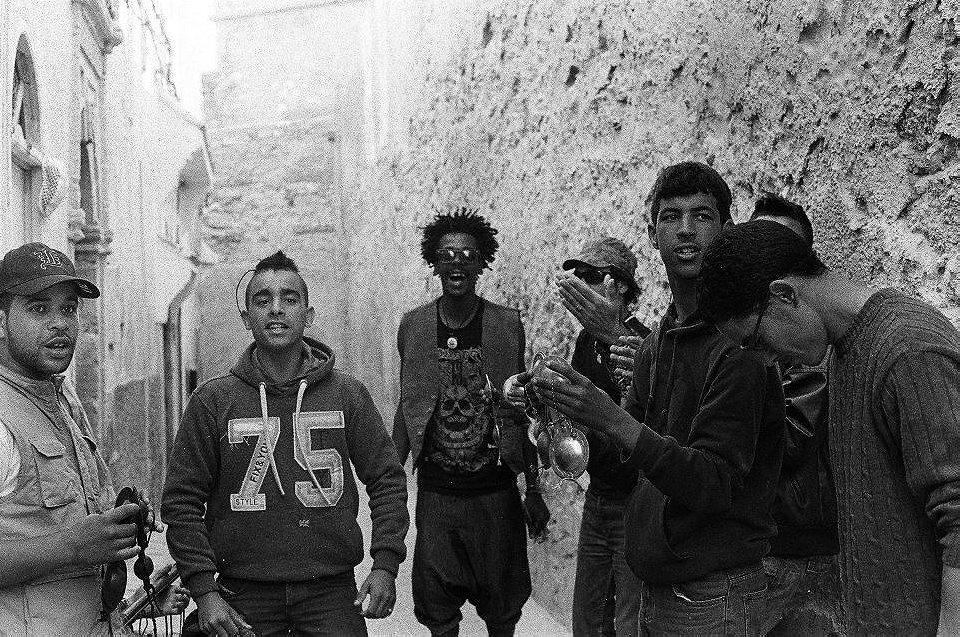

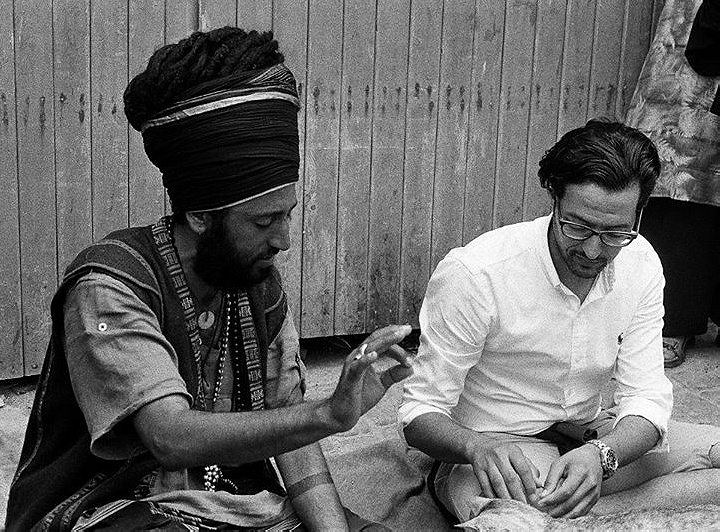

During four days spent walking around the small city, I stumble upon three impromptu musical performances. The most arresting is a five-minute Sufi chant, sung by two men, one dressed in a button-down oxford and tortoise shell glasses, the other with a towering crown of woven hair. The audience is silently pressed against each other, sweating under the sun and collective weight of the crowd, dutifully recording on their iPhones. The singers get up as nonchalantly as they had sat down, and walk away.

In recent years, the festival has attracted nearly half a million attendees. I hear similar sentiments echoed repeatedly from festivalgoers: Essaouira is unique; there is nothing like this festival.

“It’s a focus on Africa,” Sarah, a 21-year-old from Lille, France, says when I ask her why she chose Essaouira over the summer festivals in Europe. Indeed, the festival’s promotion and preservation of North and West African music on an international platform is unique. Essaouira’s long-standing allure to musicians, the relaxed beachside location, and the passionate and exuberant performances all add to the energetic vibe that engulfs the festival.

But at the same time the Gnawa Festival, which descends upon Essaouira choking the city’s narrow streets with thousands of foreigners is a source of cultural contention. For one, the promotion of fusion and cultural exchange is largely contained to the stage.

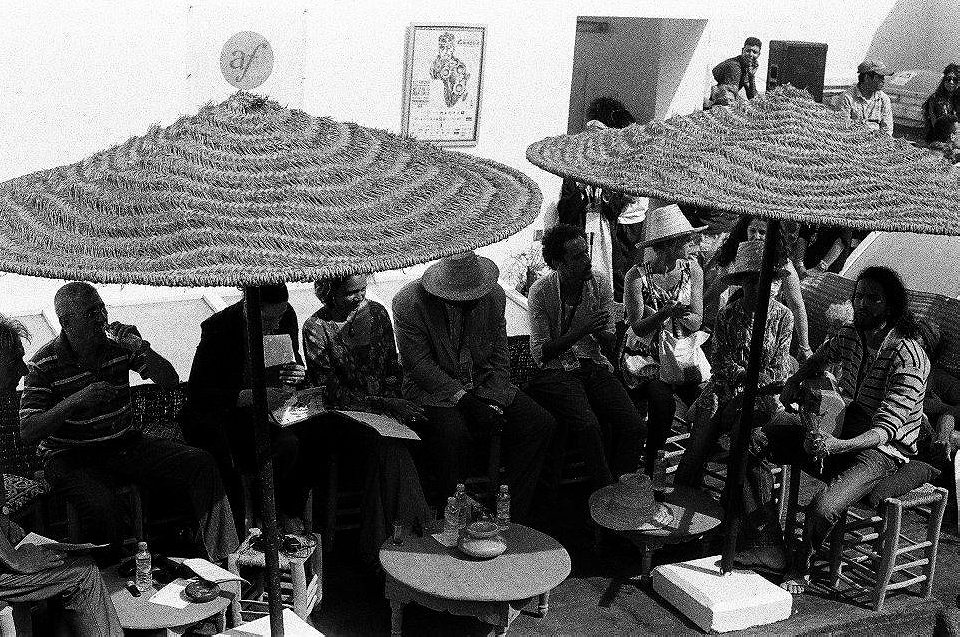

“Obviously it’s an enjoyable experience for them [Gnawa musicians] but they don’t benefit from the concerts,” a musical anthropologist tells a crowd of cerebral festivalgoers at L’arbe à Palabres, a discussion organized by the Gnawa Festival. “Their music doesn’t get sold internationally… [they] are still poor, and they’re still looking for ways to fix their economic situation.”

He points out that there are no conservatories or educational centers in Essaouira for the musicians, and they receive little financial compensation for their music. Western musicians that come to Morocco are in a position of economic privilege and power, creating a one-sided exchange. The fact that many of these richer, more established musicians are from France, a country that colonized Morocco for forty-nine years adds another layer of separation.

It’s not fusion when another musician comes to Gnawa for two days.

There must be something about Gnawa that promotes a cultural exchange in a meaningful way- after all, as the moderator Emmanuelle Honorin points out, the maâlems don’t necessarily change their sound for visiting Western musicians. “Yes, but it’s not fusion when another musician comes to Gnawa for two days [to play music and leave],” says Kif Samba’s Yassin. “Real fusion demands a lot of work.” Emmanuelle agrees, telling us, “I don’t believe in fusion-fusion, confusion, profusion, infusion… we’re here to interrogate this word.”

I speak with Mouad, 30, in his spice shop, under the shadow of an abandoned Portuguese church that is now home to several dozen stray cats. He scoffs at the notion of cultural exchange. “The musicians aren’t even that good. They’re taking Gnawan music and mixing it with Brazilian music. What is that? You wouldn’t mix couscous with tagine!”

I think of my lunch, where I had done just that, but keep quiet. “The festival is bad,” Mouad continues bluntly. “This isn’t for us [Essaouirians] anymore, it’s not for families. Now it’s shebab [young people] that come, and they are causing problems, they are fighting. What does it do for us? There are lots of girls and boys that come here…” he lowers his voice and crosses his arms. “They are sleeping together, and they are not married. There are preservatifs [condoms] everywhere. So what does the festival bring us? AIDS.”

Though condom usage would technically negate the spread of venereal diseases, others echo Mouad’s thoughts. “We used to have a traditional culture here,” Brahim tells me. “The festival has changed this a lot. In some ways it’s good, because we see new things, but in other ways, it’s not.” Mounim, 33, also a shopkeeper, agrees. “The last good festival was in 2004,” he said from his perch amongst rows of pirated CDs in the music store he works in. “It’s better if there’s no festival.”

Despite the animosity some Essaouirans feel towards the festival, it is firmly staying put. “With all these divisions in the world, all this racism and hatred, music brings us all together,” a middle-aged Frenchwoman says during a L’arbe à Palabres discussion. “What else is there besides music?” She pauses for a moment. “And love. Music and love.”