In the highlands around Mumbai, practitioners of Mallakhamb perform curious acrobatic feats using poles, ropes… and castor oil.

MUMBAI—

In 1936, a troupe of 35 acrobats from a small town in Central India traveled to the Berlin Olympic Games to demonstrate the ancient sport of Mallakhamb. At a formal gala convened by the International Olympic Committee, athletics officials and eager media from around the world gathered to witness the 900-year-old exotic sport’s global unveiling. The team’s intricate feats of contortion, strength, and death-defying gymnastics atop a skinny, eight-and-a-half foot pole thrilled Adolf Hitler; the Führer personally bestowed each acrobat with an honorary Olympic medal before the group returned to India.

The world’s first real glimpse of this curious athletic form was also its last. But today, in the lush highlands that hug sprawling Mumbai, this peculiar sport with apparatuses that look uncannily like medieval torture devises is still practiced. It is in these few ramshackle gymnasiums scattered throughout India’s Maharashtra—the same region where Mallakhamb’s origins are traced back to 12th century Sanskrit texts—where a strange tradition that features swinging clubs, rope burn between toes, and copious amounts of castor oil—is kept alive.

Athletes perform 90-second routines packed with intricate skill combinations as a panel of three judges assesses each competitor’s speed, grace, and difficulty on one of the sport’s three apparatuses: Pole Mallakhamb, Hanging Mallakhamb, or Rope Mallakhamb. It is an insular sport that exists nowhere else in the world. And although its sole governing body—the Mallakhamb Federation of India—organizes a handful of national competitions each year, the sport is mainly a Marathi Hindi practice. In a country where cricket is thought of as the unifier of over one billion people, Mallakhamb is a blip on the radar—an eccentric regional phenomenon largely tucked away in Maharashtra.

“Mallakhamb is history’s hardest sport that no one knows,” says coach Uday Deshpande before he catapults into a forward flip, landing four feet up a wooden pole by catching it between his thighs. With roots in Hindu monkey god mythology, bellicose ancient fighting traditions, and an unexpected brush with British colonialism, Mallakhamb may be history’s oddest sport, too.

Deshpande, a legendary guru and one of the sport’s foremost authorities, knows Mallakhamb better than perhaps anyone.

Though he carries a deceptive slouch in his slight frame, the sprightly 60-year-old still rises before dawn each morning to head the training facility in central Mumbai. For four decades, Deshpande has ushered over 50,000 students into this cramped, derelict building of corrugated metal and crumbing cement. Although the gymnasium now sits in the shadow of encroaching skyscrapers, his institution is one of the few physical education facilities left where traditional Indian sports like Mallakhamb are cultivated amid the crush of modern Mumbai.

Mallakhamb looks like no other sport on the planet

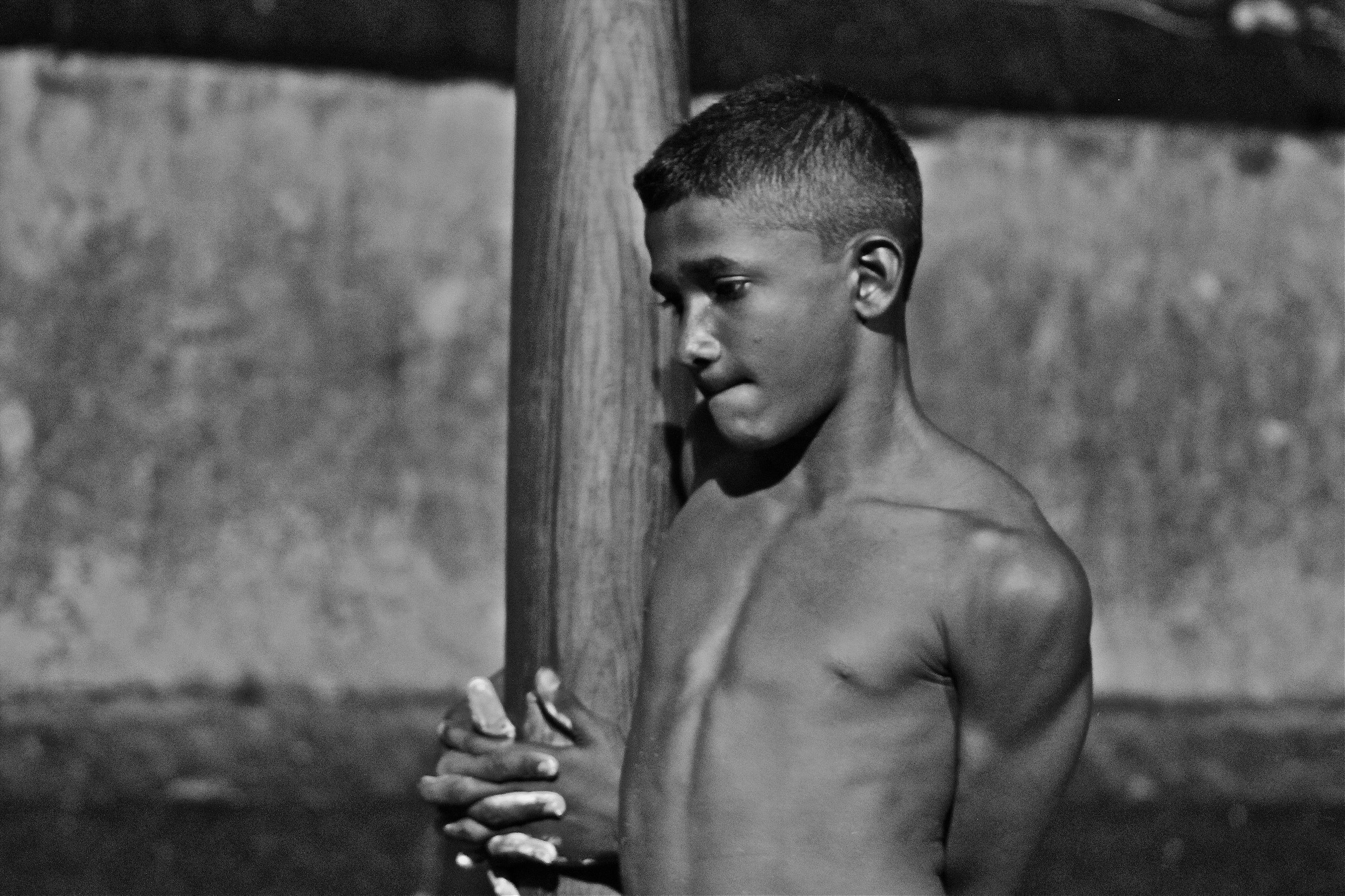

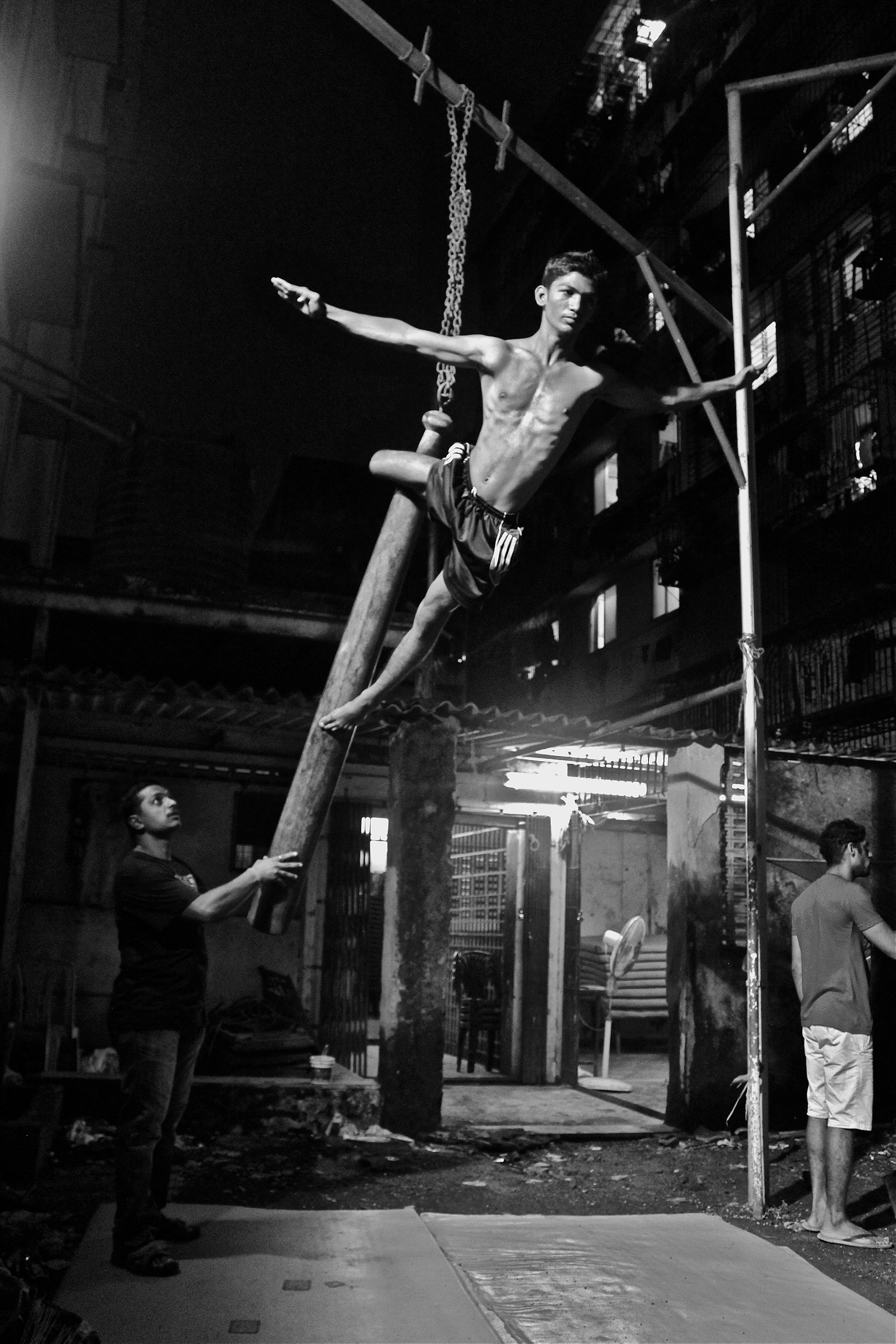

Upon first entering his dusty gym and witnessing the training regimen, the most remarkable thing is that Mallakhamb looks like no other sport on the planet. Even its three apparatus—the Pole Mallakhamb, the Hanging Mallakhamb, and the Rope Mallakhamb—appear bizarre, almost cartoonish. In one corner, boys practice Pole—greased up in castor oil, they shimmy along a tall wooden rod, tapered to a mere inch diameter, while executing Herculean skill sequences under threadbare mats: sideways hangs with one arm; upside-down slides using one leg; straddles, splits, and superhuman balancing acts utilizing an endless variety of hand, foot, knee, and elbow grips. A few feet away, the Hanging Mallakhamb seems even more formidable as plucky five year-olds navigate the same risky skills on a shorter, squatter pole that twists and twirls with each body movement, swinging through the air like an immense wind chime.

In another corner, girls practice Rope near an old file cabinet covered in cobwebs and trophies. Clutching the braided cord between their toes, they climb upwards, performing intricate shifts of their weight to form lassos around a leg or an arm that catch the body as it cascades downwards into dumbfounding yogic positions—a Sisyphean act of scaling, falling, then re-scaling the rope like a Jacob’s Ladder toy.

“Mallakhamb is a sport of discipline. It is an Indian sport,” Deshpande says without making eye contact, stroking his close-cropped beard as he closely observes an eight year-old girl summersaulting down a rope. A loop of it cuts sharply into her ankle to stop her trajectory and prevent a fall to the floor. She barely flinches. Suspended four feet in the air upside down, the young acrobat effortlessly grabs her leg behind her head as Deshpande makes slight adjustments to her positioning like a Soviet ballet master. Her muscles twitch and—in an instant—she’s climbing back up the rope under her coach’s steely gaze.

“We strive for perfection in our sport,” says Rajesh Amrale, a renowned former national competitor whose Mallakhamb demonstrations led him to the finals of India’s Got Talent in 2009. “Even in India, people haven’t seen Mallakhamb and don’t believe it when we perform,” he adds, grinning.

As students grab their shoes from a rack and head out the door to school, Deshpande saunters to his musty office. He retreats to the yellowing books and papers on Ayurveda and Indian sporting traditions that line the cupboards along his walls, pulling out Mallakhamb’s limited literature for consultation.

Originally developed as a training methodology for wrestlers, Mallakhamb’s own name entwines Sanskirt and Hindi to literally means “pole wrestling.” The ritual of greasing both the equipment and athlete in castor oil mirrors the Indian kushti wrestling tradition of dousing both ring and wrestler in ghee.

The pole represents the Hindu monkey god’s

phallus, which is why Pole has no female practitioners

The climbing, joyfulness, and irreverence of Mallakhamb are said to be informed by the spirit of Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god, and its strange apparatus reflect his anatomy: the pole is his phallus (which is why Pole has no female practitioners) and the rope is his tail (which is why the rope is exclusively climbed with toes, as using the soles of feet would be disrespectful).

After the sport’s initial introduction in the 11th century, Mallakhamb resurged in a fantastical merging of history and myth. Hanuman is said to have appeared to the famed physical trainer of the Marathi kingdom’s royal prime minister, Balambhatta Dada Deodhar, in the late 18th century, after he was challenged to a wrestling match by sinister outsiders. The trainer watches Hanuman climb a tree and acquires the monkey-god’s skills, learning to mimic Hanuman’s strength and agility.

“It has a colorful heritage and strong regional roots, so India should be proud,” Deshpande says, rifling through more cabinets.

Carefully flipping through fragile pages listing the detailed history of his top students and their accomplishments—he’s coached national champions each year since the competition’s inception more than 30 years ago—Deshpande sighs as a cricket ball sails onto the gymnasium porch. He smiles and waves over a sheepish young boy to come retrieve his ball.

“Why don’t you come try Mallakhamb instead?” Deshpande says as he sends the boy off, cricket ball in hand. The kid rejoins one of five simultaneous cricket games bleeding into one another in the nearby dirty lot, his uniform blending with the sea of other players. “It’s a sport of colonialism,” he sighs again, before turning back to his aging books. And though it would be easy to dismiss Mallakhamb’s peculiarity as the product of endemic isolation, even it didn’t escape a run-in with Western imperialism.

Though British colonialists did their best to outlaw traditional Indian athletic practices, such as kalaripayattu martial arts, Mallakhamb largely flew under the radar until the 1920s, when Indian nationalism reached a fever pitch and the sport became a symbol of Indian heritage for some. But the formation of a unifying governing body—the Mallakhamb Federation of India—to officially define the odd training form as its own sport emancipated from wrestling led to standardizations that drew upon the traditions of western gymnastics—like the inclusion of certain established moves, prescribed routines, and time limits.

Deshpande reaches for a small, tattered book next to a photograph of his grizzled father, an Indian freedom fighter, the man who encouraged him to attend Mallakhamb practice each day as a boy. Inside the book, neatly drawn diagrams of men standing atop poles outline the rules and regulations of the sport. Though some of the skill names look unfamiliar, stitching together Hindi and Sanskrit, other later era terms lift directly from British gymnastics. As students pour in through the front door, he rifles quickly through the manual, a melding of the languages and images of Mallakhamb dancing on the page like a flip book turning backwards through time.

“Pole dancing is famous in the whole world but our sport with one thousand years of history is forgotten,” laments Ravi Gaikwad, a former competitor who now coaches in Mumbai in the hopes of keeping Mallakhamb alive for the next generation.

Later that evening, his students from both the morning and afternoon sessions gather outside in the wide lot, kicking up red sand in plumes as they walk. While they strain to carry the bulky equipment out into the open air for a rare public performance, Deshpande lowers his voice. “Actually, I do wish Mallakhamb could be back in the Olympics,” he says.

As the full team of students marches out together in lockstep before a gathering crowd, Deshpande recalls fondly Mallakhamb’s one big moment on the international stage. The time when 35 Mallakhamb acrobats, marching two steps behind the official Indian contingent waving the Union Jack, solemnly carried India’s independent saffron flag. “Their incredible feats of athleticism awed the world,” Deshpande says. “And the world should know about Mallakhamb once more.”