A century ago, a hero rose up from the Ukrainian heartland who fought for neither east nor west.

Like its present, Ukraine’s past is often seen in terms of split identity, torn between Europe and Russia, sitting along the fracture of different civilizations. For hundreds of years and for much of the 20th century, the country saw its fortunes determined by powerful outsiders. Russia claimed its birthplace in Kyiv. Those in the western portions, including the great nationalist hero Stepan Bandera—incidentally also a World War II-era Nazi collaborator—kept Ukraine pulled toward Europe.

But a less well-remembered historical figure offered a different vision, one opposed to both sides. Nestor Makhno wanted a radically independent, anarchist future in Ukraine, free from the pull of both east and west. For three years in the wake of World War I, he succeeded in constructing a free state along the banks of the Dnieper River, bridging the divide between Russian-speaking and Ukrainian-speaking peoples. It was an audacious, improbable republic, and though it crested a century ago, Makhno’s country is worth remembering because it was perhaps the last time Ukraine was truly free.

Makhno’s ideas remain marginal and his legacy localized. When the town of Huliapole in southeastern Ukraine—Makhno’s birthplace—celebrated his 125th birthday in October, it was a relatively muted affair. There was no nationwide remembrance. There was no hero-worship. Makhno’s anarchist dream seemed the relic of a time long past. Scowling under a papakha in the center of town, his statue stood alone.

In the pantheon of Ukrainian freedom fighters, Makhno lies in the shadow of the ur-nationalist Bandera, the default anti-Moscow figure. It is Bandera’s orange-and-black flag that denotes the bloodlands of the Ukrainian west. It is Bandera’s name Russia now invokes when it denounces the supposedly fascist leanings of Kyiv’s new pro-western rulers.

Bandera was a fairly straightforward national hero, and villain. His was an arch-nationalist with a state-first thirst for independence, no matter the means, no matter the allies he took on. Makhno remains a much foggier character. His legacy is less amenable to jingoistic cooption. His political platform was one of fleeting, fiery mayhem—not just against the land-owning class or any imposition of domineering foreign control, but also against the very idea of a state itself.

So instead of just wanting to liberate Ukraine, he wanted to fundamentally re-order the shape of Ukrainian society along anarchist lines, to turn the country’s vast, exploited peasantry into a vibrant network of self-governing communes. In a sense, he wanted true independence for Ukrainians: independence from the Soviet Bolsheviks, from German and Austrian aggressors, and even from the Ukrainian state itself. As such, the people who truly look up to him are not necessarily Ukrainians, but instead the free people of Christiania, or the squatters of Brixton, or the fighters of Revolutionary Catalonia.

Makhno was born into a peasant family in southeastern Ukraine in 1888. His poor upbringing promised a life of livestock and languish—and the early death of his father seemed to seal his fate.

But as Russia blundered into the 20th century, faltering against the Japanese and creating a Potemkin parliament, Makhno’s world began to shift and open. In his teens, he joined an anarchist group called “The Union of Poor Bread Growers.” They robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Robin Hoods of the Dnieper. The authorities clamped down, and only a forged birth certificate that made him seem younger than he was spared Makhno from being hanged with his comrades.

His continued political agitation eventually landed Makhno in Moscow’s Butyrskaya prison in 1911. In jail, Makhno received the education he had foregone, soaking up political treatises and theories in the company of Pyotr Arshinov, a Russian anarchist who was serving a 20-year sentence. When Makhno was released following the February Revolution in 1917, he returned emboldened to a homeland in total upheaval.

The turmoil of World War I encouraged a ferment of political organizations and ideologies in Ukraine. “The notion of complete self-determination, up to and including a complete break with the Russian State, thus emerged naturally among [Ukrainians],” Makhno later wrote. “Groups of every persuasion sprang up among the Ukrainian population by the dozen.” These included a panoply of factions: separatists, monarchists, Mensheviks, revanchists, German sympathizers—and anarchists, with Makhno at the center.

MAKHNO WAS AS PROTEAN AS NATURE HERSELF

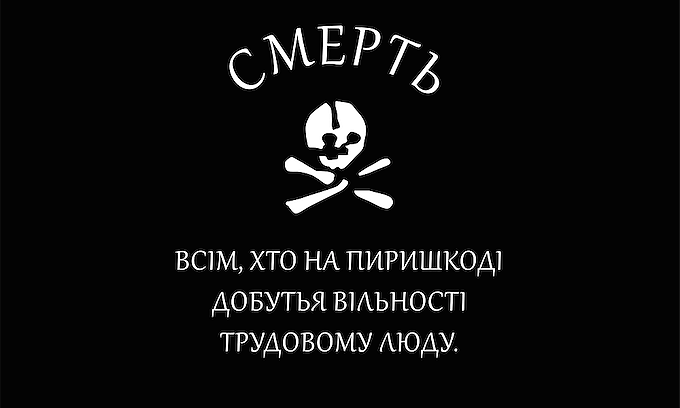

Makhno’s anarchists, gathered under black banner, played a large role in the Red-White wars that followed the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and uprooted much of Ukraine. His first targets were the garrisons of the occupying Austrian army in the region. His forces launched stealthy guerilla raids and returned captured goods to the peasants, keeping weapons for themselves. Local populations offered their support with food and horses. The charismatic Makhno gained a following and the anarchist revolutionaries soon swelled across much of southeastern Ukraine. Their inventive disguises–as Austrians, as nobility–inspired their supporters. Where authorities saw a mob, those who joined—or who were attacked—saw a wraith, dissolving as quickly as it had appeared.

“Makhno was as protean as nature herself,” an observer from the Red Army noted. “Hay-carts deployed in battle array take towns, a wedding procession approaching the headquarters of a district executive committee suddenly opens a concentrated fire, [and] a little priest, waving above him the black flag of anarchy, orders the authorities to serve up the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, wine, and music.”

Thousands soon lined up behind Makhno. His famous horse-drawn machine guns, called tachanka, grabbed many victories, and his flags soon bore the slogan Svoboda ili smert’, “Liberty or death.” A black wave unfurled through the heart of Ukraine, smothering the Austrians and Germans and their puppet installations, pushing them out as the anarchists expanded.

TROTSKY PROMISED TO CLEAR OUT THE MAKHNOVSCHINA ‘WITH AN IRON BROOM’

The Reds rapidly took notice. In early 1919, the Bolsheviks allied with Makhno and his “Black Army” against the remaining Whites, who were gathered at the time under General Anton Denikin. Makhno cut Denikin’s supply lines and forced the Whites into the Black Sea. Victorious, the Black Army sought to consolidate its gains and secure a “Free State” in southern Ukraine where the principles of anarchist organization would be practiced among the peasantry.

But the Russian Bolsheviks wanted none of this anarchy on their southern flank, and promptly turned on Makhno’s forces. Leon Trotsky was dismissive of the anarchist cause. “[Makhno] was a mixture of fanatic and adventurer… [who led] well-fed peasants who were afraid of losing what they had.” Trotsky promised to clear out the Makhnovschina “with an iron broom.” He outlawed the anarchists, and declared Makhno an enemy of the nascent Bolshevik state.

Makhno survived an assassination attempt by the Cheka–the precursor of the KGB. Heavy fighting and guerilla warfare ensued. Tens of thousands rallied around their bat’ko, or “father” as Makhno was known. The brutal struggle between Bolsheviks and anarchists raged over swaths of Ukraine until 1921, interrupted only briefly when both sides united again to defeat a resurgent White Army. Eventually, however, the Reds came too strong, and too numerous. The inherent contradiction of organized anarchy set in, and the Makhnovschina were scattered. Makhno fled to Romania, then to Paris. He died of tuberculosis in 1935, never seeing the realization of his goal of anarchism in the plains of Ukraine.

The bat’ko’s legacy limps on, still waiting to ossify. Governments are still, and will remain, averse to the anarchy he advocated. But only a month after Huliapole—which has nicknamed itself Makhnograd—honored the memory of Makhno, the EuroMaidan movement began, shaking the country, toppling its pro-Russian president Victor Yanukovych. Russia has invaded Crimea, and is threatening more. The West blusters and threatens in response. A standstill hangs. Makhnograd stands restive. And that anarchy—that black flag under which Makhno fought, and for which his thousands died—looms just beyond.