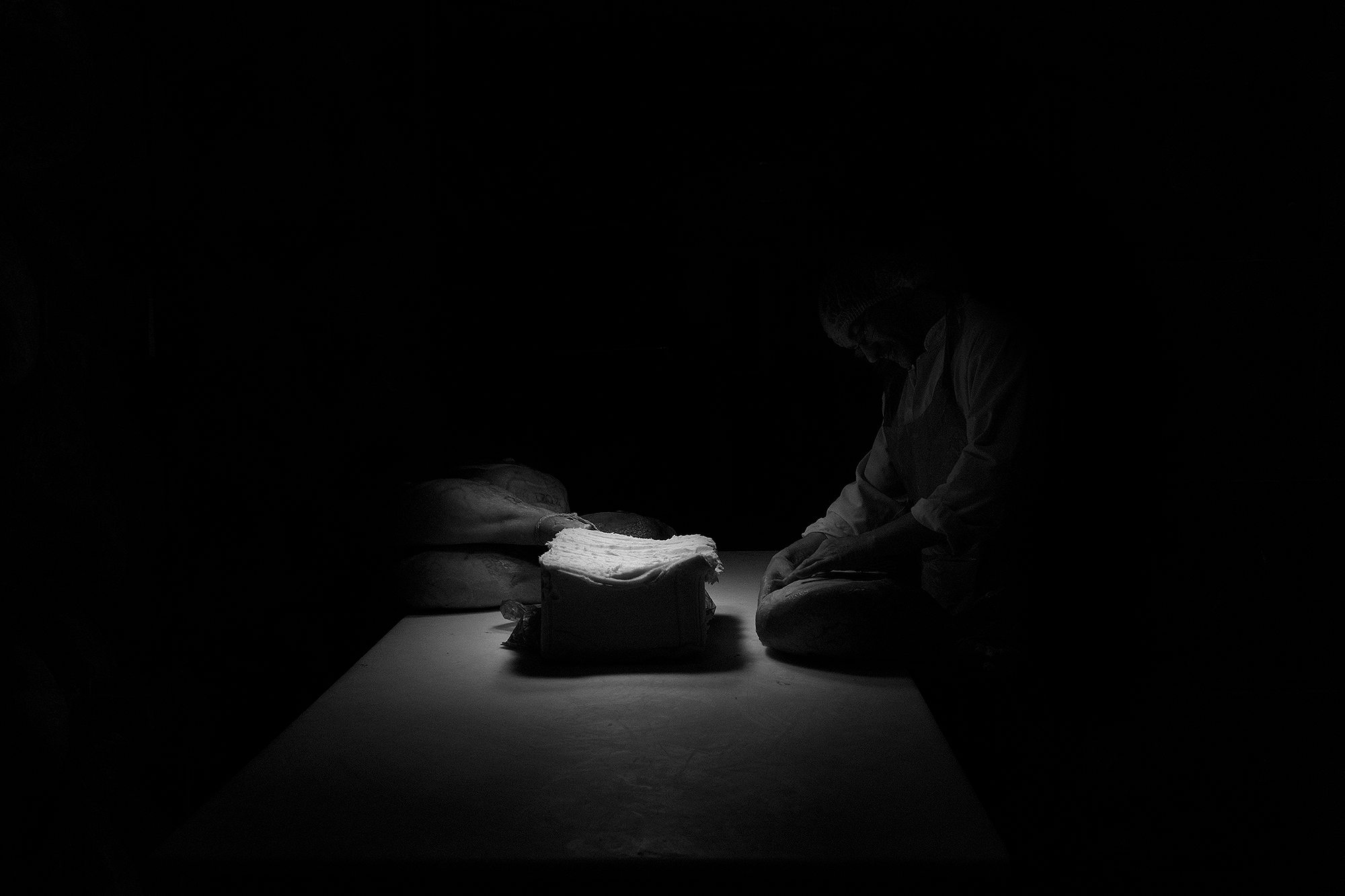

Making Parma ham the right way requires an assembly line of skilled craftsmen. Photographer Alessandro Iovino visits Il Gazzolo Di Alberto Galloni e Figli, a producer in Langhirano located 15-minutes from his hometown of Parma.

In the winter of 2008, police officials in northern Italy seized 1,000 suspicious hams from supermarkets, warehouses and family-run shops, pegged as Prosciutto di Parma imposters. The counterfeit ring was foiled when a special task force of food detectives recognized an irregularity in the famous five-pointed Parma crown that comes stamped onto every leg of authentic prosciutto.

“Procedures weren’t respected, and so the prosciutto didn’t have the same quality, the same aroma and the same sweetness,” Umberto Santone, head of the Carabinieri anti-fraud unit, told the AP. Others hinted darkly that the counterfeit ring was part of an even larger and more sinister operation to cash in on inferior pig.

Prosciutto di Parma is the world’s most famous ham, one found in polished restaurants, discerning pizzerias and high-end delis the planet over. It may not be the world’s greatest ham (that distinction belongs to the Spaniards and their acorn-fed, black-footed pigs), but it’s a product whose quality is regulated with a clinical intensity.

The Consorzio del Prosciutto di Parma, the “official body in charge for safeguarding, protecting and promoting” Parma ham, runs a tight ship, with a website translated into five languages and a staggering 156 producers under their umbrella. Beyond promoting prosciutto to a global market, their primary job is to ensure that the recipe remains unchanged from the days of the Roman empire: pig and salt, brought together for no fewer than 12 months in massive curing rooms where temperature, humidity and sunlight are carefully monitored—a meticulous process enforced by a team of inspectors that look like country doctors making house calls.

Making Parma ham the right way requires an assembly line of skilled craftsmen, each who handles one small part of the killing, cleaning, butchering, salting, hanging, and curing that goes into every prosciutto. To document the craft, photographer Alessandro Iovino visited Il Gazzolo di Alberto Galloni e Figli, a Consorzio-approved producer founded in May 2014 in Langhirano, a 15-minute drive from his hometown of Parma.