Roads and Kingdoms’ Alexa van Sickle braves sea urchins, jagged rocks, and myopic U.S. foreign policy to surf Havana’s Calle 70 break.

I had my fears about landing in Havana with a surfboard. The things aren’t illegal, per se, but the Cuban government—until its recent moves to make traveling out of the country simpler for Cubans—had been sensitive about any flotation devices that could aid would-be defectors. And there was that 2011 report in state-run media that the CIA tried to bring in surveillance equipment disguised as surfboards in a fake surfing contest.

In any event, the surfboard, which I bought in South Padre Island, Texas, is released later from a special bulk items area and raises no interest from officials or their bored-looking sniffer dogs. Other passengers are similarly unmolested as they cart away crates of shampoo, TVs, office chairs, and a half dozen Firestone tires destined either for families or, more likely, the black market.

The final destination for my cargo is a three-room apartment in Buena Vista (of the Social Club) in western Havana, where Eduardo Nunez Valdes, 33, lives on the top floor of a narrow, pink building. Valdes is the founder of the Cuban Surfrider’s Association—although it’s a more informal group than the title suggests; in Cuba, independent associations are neither recognized nor supported.

The board is my small contribution to an unusual network of donations that Valdes and Australian-based Blair Cording have set up to help Cubans get in the water: boards and other equipment such as wax, resin, tape, or even computer equipment.

“The whole operation is just two guys, collecting things from miles away and trying to get them to Cuba… Imagine what we could do if we had more resources,” says Valdes.

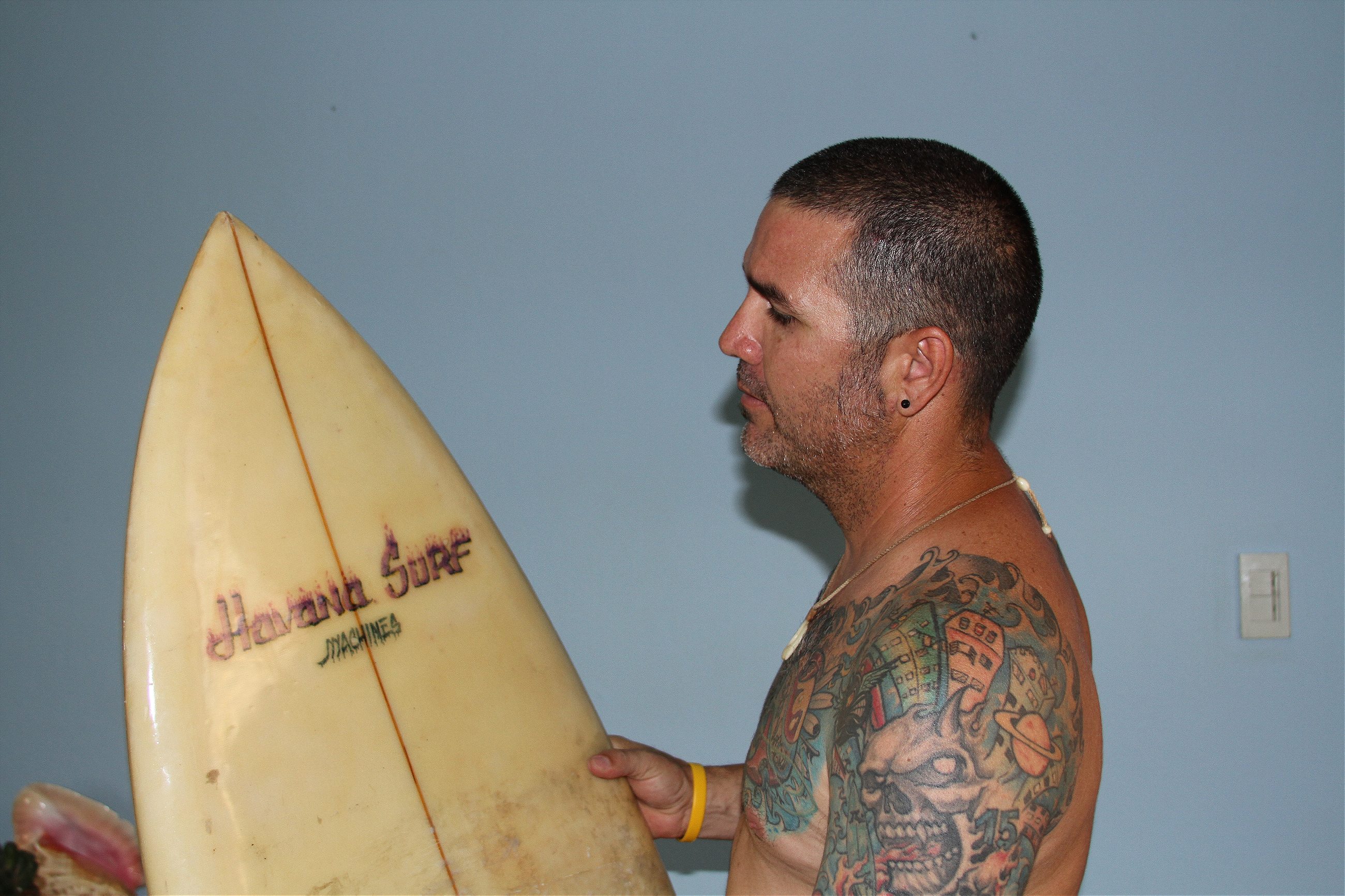

Valdes has close-cropped dark hair. A third of his body is an intricate canvas of colorful tattoos; his chest and shoulders, up both arms, and down one leg. His left arm promises to “Never Stop Surfing”. Sometimes, he says, people call him ‘the Farmer’ because his mother is from Pinar del Rio—Cuba’s agricultural western province that is the butt of many jokes in urbane Havana. He studied Chemistry in Havana but mostly works in construction these days. His refrigerator is covered with surf brand stickers, magnets, and quotes, from New Zealand, Mexico, Hawaii, and also Devon, England.

Cording connected with Valdes by email in 2009, when he was writing a story for ‘Surfing World’.

“I became attached to the Cubans’ passion for surfing—when they had nothing—and decided to do everything I could to help them, and get more kids on the island in the water,” said Cording in an email.

Trying to navigate the embargo, though, has been what Cording calls “an utter shitfight… one of the hardest things I have done in my life.” An example of the perils of grassroots sports diplomacy: Last year Cording worked with a local sports club in Sydney who wanted to go to Cuba and donate money they had raised to a local Havana rugby team. Cording gave the club some of his own cash to get to Valdes for surf resin, tools, and computer parts.

The Sydney club—against Cording’s advice—transferred the cash through a bank account that passed through the U.S. and Spain.

“The Americans confiscated the money, and sent the sports club a case number telling them to take the US Government to court if they want the money back.”

Small wonder that it has taken almost 20 years to build what they have. Another Australian surfer set the ball rolling. Bob Samin, a former oil-rig worker living in Cuba, helped Cuban surfers in Havana set up the Havanasurf website back in 1999—almost medieval in Internet terms. (Cuba—although by no means its general population—has been online since 1996, with the help of satellite technology.) Samin, who now lives in the surf town of Puerto Escondido, Mexico, traveled nearly all over Cuba to find the island’s best surf breaks and list them on the site, along with details of how to donate equipment, and a Spanish-language manual teaching beginners how to read wind, waves, and breaks. Others have added to it over the years, and the site has become a crucial link between the Cuba’s surf community and the outside world.

After the website went up, people began to arrive, leaving boards behind, and awareness grew in increments. In 2008, looking for surf while studying in Havana, Cuban-American filmmaker Rod Diaz McVeigh discovered the website, and eventually made the documentary ‘Havana Surf’;. Then came the 2011 film ‘Surfing with the Enemy’—by Venice Beach-based film-makers—an account of traveling around the island with six Cuban surfers, including Valdes, to find a surf spot in Guantanamo, just a couple of miles from U.S. territory.

But still, in a country of 11 million people on an island with over 3,500 miles of coastline, Valdes estimates that there are fewer than 150 surfers—including just two women (one of whom is a boogie boarder). Some might see that as a pitifully low number; Valdes sees it as a sign that sport has plenty of room to grow.

Despite the embargo, about 80% of the people who come to donate boards are from the US

Cuba is not known for big swells because it is blocked from most Atlantic Ocean wave action by the edge of the Bahamas, but there is a consistent winter swell around Calle 70 in Havana, and in the summer, in the eastern Guantanamo province, near Baracoa. Cuban surfers also take advantage of swells from hurricanes.

Once equipment gets to Valdes, he oversees the distribution of surfboards to the surfers or kids, depending on the type and size of board.

“The best or most advanced boards go to the best surfers,” he explains. “This makes people want to get better.” Boards then get handed down the line to somebody else. He also makes sure surfers in other provinces get boards too.

“Despite the embargo, I would say about 80% of the people who come to donate boards are from the United States,” says Valdes. They tend to be young, mainly from California, who find Valdes through the site or documentaries and travel via Mexico. He also learned his fluent English mainly as a result of this surfing venture; he had to decipher the first emails from foreign surfers planning to visit.

The American travelers and surfers who contact Valdes often visit in violation of the U.S. embargo. The main legal way to make it to the island is through “people-to-people” cultural exchanges, where visitor activities are confined, by an odd collusion between U.S. and Cuban agencies who approve the detailed itineraries, to jam-packed schedules.

I meet many of these groups in larger hotels—where I loiter for Internet access—puffing contentedly on the cigars and missing out on the best of Cuba. U.S. enforcement of the embargo on tourism in Cuba has waxed and waned over the years—a dreaded violation letter from the U.S. Treasury Department sometimes resulted in massive fines, but are, anecdotally, rarer these days. And true people-to-people connections, often through shared passions like surfing, or art, are stronger than ever between the U.S. and Cuba.

Valdes describes himself as a “second generation” Cuban surfer. “We learned how to surf on these,” he says, handing me a piece of plywood no larger than a cafeteria tray.

The first generation of Cuban surfers, starting around the 1980s, created their own boards by stripping the foam from refrigerators, sticking the parts together to form a blank, and then shaping them with cheese graters. They used glass and resin sourced from boat builders, on the black market. And somehow they managed to wrestle all this into something resembling the actual surfboards left behind by foreign surfers.

The 1950s cars in Cuba are often called ‘Frankensteins’ because they are held together—barely—with so many different parts. The same could be said of Cuba’s surfboards. Valdes is also one of Cuba’s only board shapers, and is often called upon for repair jobs. He once used metal splints to patch a board together. In a corner of his front room is one of 22 boards he has shaped himself: a shortboard he conjured out of a former longboard. “Maybe one day it will go in a museum,” he says.

Among my offerings for Valdes was a bottle of duty-free whisky, the arrival of which precipitates an impromptu gathering at his house. Cubans share everything, he says; waves, food, drink. Friends gradually fill the apartment. All have cell phones, but this party, like most of the country, is entirely offline. No one checks their Facebook or shows anyone YouTube videos. It is not yet possible to access the Internet through smart phones.

Cubans can now purchase access to the Internet to use in offices or ‘telepuntos’ run by ETECSA, the state-run telecom monopoly, but Wi-Fi networks are rare and mainly reserved for tourists, and never free. Online access in Cuba is slow, some sites are censored, but most of all, it is expensive. An hour at a ‘telepunto’ computer costs about $6—one-fourth of an official monthly salary—and still the lines to use them snake around the block in central Havana.

The most recent official Cuban statistics claim that 23.2% of the island has access to the Internet, but this refers mainly to email and the national ‘intranet’. Freedom House estimated in 2012 that only 5 percent of the population had access to the Internet proper.

“I think the biggest issue for Valdes is the expense of the Internet in Cuba,” says Cording.

“We have two blockades,” Valdes says. “One from the U.S., and one from our own government.” Cording sends cash so that Valdes can buy access to the Wi-Fi in the hotels in Miramar or Playa, which have a better connection. But even then, he often has problems getting online.

With no access to the U.S. communications cables in the Caribbean, Cuba relied on satellite technology until Venezuela helped it build its first fiber-optic cable in 2013. Officials say that it will be long time until there is widespread access; upgrading the infrastructure will require a huge investment.

Meanwhile, in true Cuban style, they’re inventing ways around the problem. As the sun sets, Valdes points out of his back window at a rooftop a few hundred yards away where, against the twilight, I can just make out a small antennae, with a small square box on top. It is one of the illicit Wi-Fi networks proliferating across the country. They are smuggled in pieces and, once assembled, have a range of about 5km. Cubans can buy access to these networks on the black market, such as on Revolico.com, a sort of illicit Cuban Craigslist.

Even with increased access, Cubans have had little online access to information about their own country; Valdes shows me some magazine articles—ranging from the New York Times Magazine to obscure surf-fashion journals—containing articles about Cuba that people have brought him over the years. He points at a full-color photograph of a table-shaped mountain near Baracoa called El Yunque, now a popular hiking destination. “Before I saw this this article, I had never seen what it looked like,” he says.

When a cold front comes in to Havana, waves crash over the edge of the famous promenade, the Malecon, making cars swerve to avoid the spray. A cold front is what Valdes and his surfer friends wait for.

Without the luxury of web-based surf reports and swell forecasts surfers rely on elsewhere, Valdes is a human surf report. From his balcony in Buena Vista, looking towards Playa, he can see a sliver of the ocean.

“You learn how to tell if the cold front will be strong enough for waves,” says Valdes. “Then I look from my balcony, and then everyone calls me to check if it’s worth coming down.”

The water’s edge at Playa, west of Miramar, lies well beyond the end of the Malecon, which has been restored in some segments, but is still blackened and crumbling in others. In this part of the city, the water’s edge is lined with sharp, jagged volcanic rock that Cubans call ‘dog’s teeth.’

I meet Valdes and Yaya Guerrero, 31, in the parking lot of the Panorama Hotel on an overcast Sunday with a menacing sky, to take the short walk to the Calle 70 surf spot. Nearby is the imposing Russian Embassy, and along the water’s edge are empty-looking Soviet-style towers. Guerrero works at the National Aquarium, a mile or so from Calle 70, where she is head sea-lion trainer.

Valdes admits that surfing is hard for women here, but not because of any machismo on the part of surfers.

“We like having women surfing,” he says. “It’s more fun than if it’s just guys all day long. We support Yaya; we give her the best waves.” (The “best waves” are also reserved for the handful of foreigners that make it to Calle 70, because they are such rare visitors.)

“But where we surf, the conditions are hard, with rocks, sea urchins, and a strong current; a reef break is not like a point break. There is no real access point. It’s a fight to get in there.”

The surf spot’s only access point is a slippery slab of concrete jutting out of the ocean, which Valdes says has been there since his grandmother took him to the beach when he was a child.

“This part of the coast used to have fishing stores,” Valdes says. “The walls of the stores were made of a foamy, hard substance.” During the Special Period—the decade of economic hardship following the collapse of the Soviet Union—the stores collapsed and were abandoned. “We took the walls of the stores and used it to make boards; but we had to be sneaky about it because it was a crime.”

Javier Robert, a tall man whom Valdes introduces as a surfer from ‘between the first and second generation’ joins us. “Yes, I’m old,” Robert agrees. (He’s all of 35). He shows me how they used to use the plywood with his right arm, and paddle with his left to catch a wave. He also used the foam-refrigerator boards. He unpacks a green and yellow board—another foreign donation—as it begins to rain.

The walk to the water—today a dull, foil-like gray rather than the blue waters of a sunny day—is an unforgiving gauntlet of the sharp “dog tooth”, broken rum bottles and other detritus. A surfer must then negotiate the slippery concrete jetty and wait for a calm period before jumping away and paddling out with all their might, before the next set of waves can wash them back against the shore.

Anywhere else, this would not be a popular surfing spot. But Valdes said Guerrerro is known among the male surfers to have cojones; I want a pair too. I also feel I should show some female surfing solidarity, now that she has gone to her shift at the Aquarium, I will be the only female surfer here, or probably in the whole country.

What follows is almost an hour of relentless salt and punishment, endless sets of waves coming in without a break. The strong current threatens constantly to push me back to the rock; there are no-go areas full of sea urchins. I’m soon out of breath. When I drift too far to the shallow end, eventually a bearded, longhaired man paddles towards me and pulls me and by board back to the ‘safe’ zone. This is Lester Pena, 25, who works as a lifeguard for this stretch of coast—although today he is only here to surf. (Needing help from a lifeguard, off-duty or not, was definitely not part of my plan.)

As I paddle back, Valdes comes over to pull me back to the concrete and take the board; another surfer—Humberto Salinas, a small-framed, lean man with long black hair—helps me back to solid ground. According to Valdes, Salinas is known to be the best surfer in Cuba, but he has never surfed anywhere else. He rides a distinctive, brightly decorated board, left here by a female Irish surfer a couple of years ago.

Traversing back over the rock pools on my way back to the rock where surfers have gathered, I notice several chicken carcasses. Valdes explains they are from Santeria priests who bring animals and fruit to this site for sacrifices. How exactly does one sacrifice fruit, I ask. The answer: they rub the fruit on themselves during their rituals.

“Sometimes we find the leftover fruit—pineapples, whatever, and eat it,” says Valdes. “When I was trying to rescue you, I saw an orange peel.” (I think to myself that ‘rescue’ might have been overstating it a little, but I don’t argue.)

The sea gets rougher through the afternoon, and it rains off and on. In all, about a dozen surfers come and go throughout the day—with Valdes’s cell phone ringing continually for updates and instructions. Most live close enough to take a bus or walk. Because it is so hard to keep up the pastime there, the Cuban surfers that remain are truly committed. Many, like Valdes, have surf-themed tattoos. You get the sense that they would travel far for the right break on their island if they could. But the lack of transportation limits Havana surfers to Calle 70, for all its faults.

“Having a car is the dream,” says Valdes. “Then we could just strap the boards on and follow the waves.”

One particular spot in the east of Cuba would be impossible to access, even with a car. According to Magisseaweed.com, “the best known south coast spot… is a ledgy and unpredictable righthand reefbreak called Windmills… found inside the forbidden Guantanamo Bay military base.”

Valdes tells a story, maybe true, maybe not, about some U.S. Marines blowing up a small reef off the Guantanamo shore in order to create their own break.

Less disputed is the fact that Quiksilver sometimes runs surf camps for members and family of serving military there.

Surfers once needed government permission to go to other parts of the country, and in the east, the coast guard prevented surfers from getting in the water altogether, thinking they were going to leave the island. The authorities are now more aware of the sport, but police will still move the surfers on if they are in the “wrong place”, says Valdes.

On my last evening in Havana, as we sit on the Malecon’s Vedado section, Valdes talks about what’s next for Cuban surfing, and for him.

He has never left Cuba, but he has applied for a family reunification visa so that he can join his father in Miami. His interview is later this summer. He has twice been denied a refugee visa. His father, once employed by Cuban security services, tried to raft to the U.S. in the 1980s – unsuccessfully. Then five years ago he was granted entry to the U.S. as a political refugee. Valdes has not seen him since.

Valdes says he doesn’t really want to leave, but there will be more opportunities in the U.S., which would put him a better position, he thinks, to support the Cuban surfing network. He would leave Yuniel Valderrama Martinez—his “right arm”—in charge on the island. Valdes’ father is an electrician in Miami, so he would start working with him. Salinas, whose parents live in Florida, has also applied for a family reunification visa. He and Valdes both plan to settle in California. What they really want to do, they say, is surf.