In South African townships, an ostentatious youth subculture is about much more than expensive clothing.

SOWETO, South Africa—

Tolouse is wearing three pairs of trousers. The bottom pair is solid black, the second a violet floral pattern, and on top is a copper coin print that matches his turtleneck shirt. It’s April 26, the eve of Freedom Day in South Africa, marking 20 years since the former apartheid nation first held open and democratic elections.

The autumn evening temperature at Thokoza Park, located near Moroka Dam in the township of Soweto, doesn’t warrant Tolouse’s sartorial overload. But his reasoning is simple: “If someone comes up to me and says, ‘Those look cheap or dirty,’ I can show them I have two more pairs on.” Each pair, he proudly notes, cost “one point eight,” or 1,800 rand—about $170.

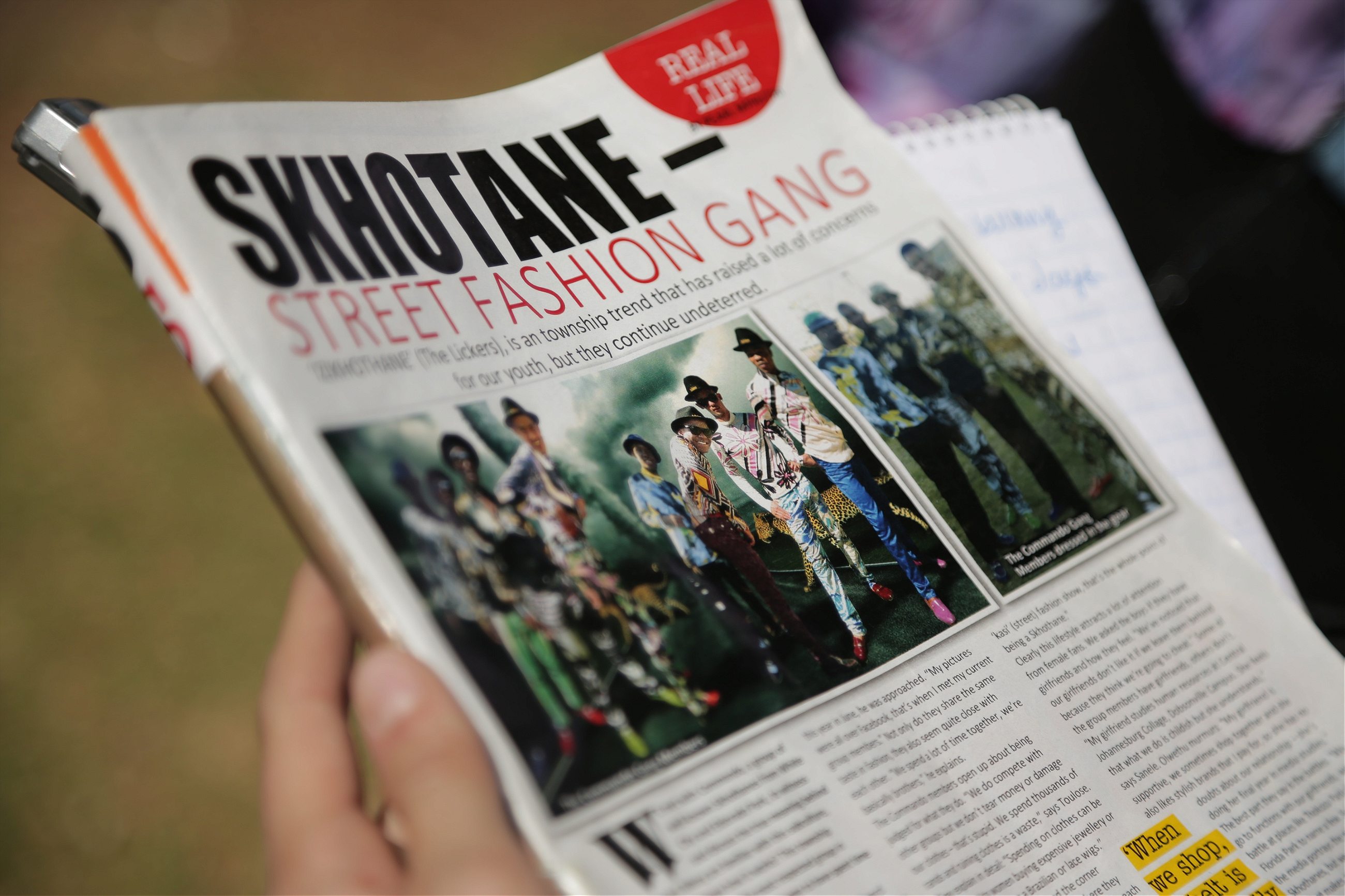

Tolouse and his similarly dressed crew, who call themselves the Commandos, are wearing outfits that, “kop to tail” (head to toe), cost up to $1,120 each. In South Africa, groups like this are called skhothanes, an adaptation of a Zulu word meaning “to lick” or “to boast.” The day’s occasion is similar to a dance-off, but the broader subculture it is a part of, known as izikhothane, is specific to the “born free” generation—those born at the end of apartheid—living in the townships of South Africa. Born-frees like Tolouse have no direct memory of a time when nonwhites lived in townships like Soweto by force instead of economic stagnation.

Many subcultures in different times and places have used ostentatious dress and exorbitant spending as a way to assert status, from 1980s hip-hop culture in the Bronx to post-communist Moscow’s uber-rich oligarchs in the 1990s. To some extent, the skhothanes are no different.

As they skhot (boast) about the names of the high-end Italian brands they’re sporting—Arbiter, Rossi Moda, Sfarzo—they never fail to mention the price tag, too. For young men living in a country where economic development hasn’t translated into what’s needed most—jobs for young people—skhothaneculture is not just a way to stand out, but a way for young South Africans to move up in a society that offers them few options. While this social mobility may be more perceived than actual, one township local summed up their motivation nicely: “When they do what they do, absolutely no one can do it better. They feel like kings.”

Late afternoon, the vibe at the leafy Thokoza Park resembles a boozy tailgate party—or, in township parlance, vula boot (“open trunk”). The Commandos’ most famous member, King Mosha—a rail-thin 19-year-old who is widely regarded as one of the best dancers in Soweto—is doing an improbable dance move that resembles planking and twerking. He effortlessly contorts his body to the deep house beat with an expression on his face that suggests, “I’m so good at this, it’s disgusting.” The crowd is loving it.

Soon another crew, known as the 18 Boys, arrives at the park, appearing to be a bit self-conscious. Their group was once so prolific that it spawned an impostor Facebook group that has nearly 39,000 likes. But for this particular occasion, they haven’t dressed up.

“Where are the 18 Boys now?” a Commando named Cheslin taunts loudly, alluding to the fact that in this crowd, an outfit costing only 300 rand renders them invisible. “I don’t see them.”

Spoko, an original member of the 18 Boys, is physically restrained by one of his fellow members. “I feel like doing it, but I’m not in the right mood,” Spoko says, referring to prospect of retaliation by way of dancing. “I’m not dressed for it.”

Skhothane culture first sprung up in the Johannesburg-adjacent townships of Soweto and East Rand in the mid to late aughts, but like many manifestations of street culture, the exact origin story depends on whom you ask.

Skhothanes were not the first to use clothes as a way to transcend township life. The swenkas of Johannesburg regarded dressing in custom three-pieced suits for elaborate fashion shows as a form of moral code. The pantsula style of dress and dance, which reappropriated the gardening uniforms black South Africans were forced to wear during apartheid, gained enough prominence that it was featured in Beyoncé’s music video for “Run the World (Girls).”

SKHOTHANE YOUTH WOULD BURN CLOTHES, MONEY, AND OTHER PRICEY ITEMS AS PART OF THEIR DANCE-OFFS

The Soweto-born fashion and photography trio known as I See a Different You are the township’s de facto ambassadors of style. With the goal of portraying Soweto “as we see it,” founders Innocent Mukheli, Justice Mukheli, and Vuyolwethu Mpantsha are acutely aware that clothing in Soweto goes way beyond aesthetics.

“Dress and swagger and what you wear in Soweto is extremely important because it defines not just your income, but your character,” Mpantsha said. “If you present yourself as a clean guy who dresses smart and pays attention to what he’s wearing, a lot of people will respect you. But if you dress in another way, people will be afraid of you or think you’re guilty of something.”

A few years ago, the skhothanes went from being famous locally to infamous nationally after crews began burning the expensive things they coveted. The habit of skhothane youth burning clothes, money, and other pricey items as part of their dance-offs and wild parties was even immortalized in an advertisement for Nando’s, a popular South African fast-food restaurant. As one skhothane explained, “If I can burn this two point three shirt, who are you? You are no one.”

In 2012, the popular South African news program Third Degree exposed the burning era of skhothane culture, causing the police to clamp down on gatherings where money was being burned, which is a crime in South Africa. While skhothanes speak of this so-called golden era with a kind of wistful nostalgia, it’s also clear that their culture is maturing as they do.

Despite this evolution, headlines such as “Why Are Poor South African Teens Buying Expensive Clothes and Destroying Them?” still persist. Such stories follow a simple logic: Removed from the struggle of apartheid, these morally bankrupt and entitled youths ostensibly see no problem wasting the money that not long ago their parents would have barely been able to earn. These headlines imply a more loaded question: Why would anyone in Soweto spend their money on anything but getting out of Soweto?

To understand why unemployed 20-year-olds walk around Soweto in $1,120 outfits, you first have to understand what it means to grow up there.

Soweto is South Africa’s largest township, with an official population of 1.3 million. More than 40% of the population is under the age of 25, and nearly 50% of young people are unemployed. Most afternoons, young and idle Sowetans pass the time loitering on street corners.

In some ways, Soweto in 2014 is a paradox: While the last decade’s proliferation of shopping malls, big supermarket chains, and car dealerships signal improved purchasing power overall, it belies the grim career prospects for the young born-free who grow up here.

At the Shoprite U-SAVE in the Mofolo area of Soweto, two liters of Fanta and a large bag of Lays potato chips costs about $2.60. A minibus taxi ride to Johannesburg’s Central Business District, 9 miles away, costs $2.80 round trip. Fifty megabytes of Internet to charge a smartphone cost just under $1.

You might expect these to be relatively small expenditures for someone like Tshepo, who is wearing trousers that cost $170. But they are not. The economic gains throughout South Africa in the last two decades haven’t helped him find so much as a job.

With fire-engine-red hair, 22-year-old Tshepo is a lead member of the Commandos. What he lacks in employment he more than makes up for in his ingenuity. On his Facebook profile, his current job exists in aspirational terms only: a senior animator at Marvel Studios. He has a low-fi production company that he calls Don Dada, which consists of him shooting and uploading videos of King Mosha’s marathon dance sessions to YouTube. He uses Internet cafes to create posters publicizing upcoming Commandos gatherings and spreads them via WhatsApp.

Despite the township’s woes, Tshepo is upbeat about living in Soweto. “I came here from the Free State province, and I live with my grandma,” he says. “I’m so glad I came here. I will live here forever. If I hadn’t come here, I wouldn’t have Internet, and I wouldn’t be in magazines.”

Greg Potterton, managing director of Instant Grass, a Johannesburg-based agency that specializes in studying pockets of youth culture in Africa, says that in a place like Soweto—which is bordered by freeways and was designed during apartheid to be isolated—Tshepo’s local pride is often a product of circumstance. “When a lot of these kids are growing up, they really don’t have much option or aspirations to go anywhere else because they didn’t know about anything else,” Potterton says. “Then, you get reverse innovation happening: In the absence of luxury, creativity is born. Over time, it’s become a cooler place to be.”

In absence of money or much chance of upward social mobility, skhot-ing gives Tshepo social currency, which has a certain value in itself. All told, the return on investment on a $1,120 outfit is pretty impressive. First there are the girlfriends, which the Commandos all claim to have in droves. There’s the sense of community (members with money help buy clothes for those who don’t). There are the paid appearances at local weddings, parties, and funerals. And lastly, there’s the recognition they receive in their neighborhoods and across Soweto. In the case of the Commandos, which has both black African and Cape Malay (referred to in South Africa as “colored”) members, this sense of respect even manages to transcend racial divides.

The general attitude toward skhothane culture has softened since the clothes- and money-burning days. Shainida Neigshaan-Smith’s son, Tolouse, is a Commando member. At 21 years old, he is unemployed and lives at home. Contrary to the common assumption that all skhothanes steal money from their parents, Neigshaan-Smith is proud of her hard-earned middle-class status that allows her to fund Tolouse’s lifestyle.

“It started with his matric [graduation]: We bought him his first two pairs of Arbiters and a custom Sfarzo suit and had a big party,” Neigshaan-Smith says. “He’s an adult already, so whatever he decides to do is up to him. But it’s nice to be able to provide for him.”

The Commandos are clearly familiar with the concept of self-branding. The career that they describe for themselves—being brand ambassadors as well as stylists, models, and tastemakers for their favorite labels—sounds similar to that of I See a Different You. With international appearances and a sizeable social media following, I See a Different You is using fashion to promote something that can otherwise be hard to find: a positive image of black South African youth from the townships.

The crew believes Soweto style can spread beyond the township. “If the skhothanes package themselves as fashionable youngsters from Africa with something different—which they are—and put themselves out there more, there’s definitely room for them to be great in the fashion industry,” says Mukheli. “We see what they do as an art form.”