India, long an importer of sports, finally has one to send out to the rest of the world: roll ball, the bastard child of rollerskating and basketball.

On my book shelf is a trophy for a sport I never played from a country I never lived in. My name is on it, right below the word “Memento”, as if I needed a reminder that playing roll ball in India would be worth remembering.

It was 2012. I was headed to Mumbai for another assignment and wanted to find something unusual to write about. I read a few stories about a hybridized form of basketball on roller skates developed in nearby Pune and fell in love with the idea of a truly homegrown sport. Most of the major sports in India come from elsewhere. Rugby, cricket and even what many consider the national sport, field hockey, all originated in England. But roll ball, which is, in its own way, being exported to almost two dozen developed countries, came from India. Besides, hardly anyone had written about roll ball. It seemed a perfect assignment, until everything went wrong in Pune.

My first emails to the International Roll Ball Federation met with sparse replies. They didn’t seem to believe that an American journalist was really planning to come to Pune to write about their sport, or especially understand why that might be a good thing for roll ball.

Siddharth Mehta got it. He was helping to promote the sport through Let’s Play Sports Management Company. It was Mehta who showed me around Pune, a software hub about 100 miles southeast of Mumbai. It’s a place where many of the customer service workers you talk to on the phone are based. A bustling city continually under construction, Pune and its young residents are on the move. The older people tend to get left behind and the middle-aged, like roll ball founder Raju Dabhade, struggle to keep up. A former national speed skating champion, Dabhade zooms around the city on a motorbike, but life for him and his cohort can be a stagnant and lacking opportunity, even for someone who invented his own sport.

I met him at a dinner that included half a dozen other roll ball players and promoters. Dabhade was the easiest to overlook, a diminutive and quiet man. It was a big, raucous event, and that first night he and I barely got a word.

DABHADE USED TO DELIVER NEWSPAPERS ON ROLLER SKATES

His story, and that of roll ball, came to me in snippets over the next week: from his students, his children, his friends and, occasionally, from Dabhade himself. In the third floor apartment he shares with his wife and two children that doubles as the federation’s headquarters, stacks of papers tied with rope document the sport’s brief history. Dabhade’s 20-something daughter, Rucha, told me about how her father used to deliver newspapers on roller skates. He rose through the ranks in roller speed skating and later, after retiring from competitive skating, became a physical education teacher. But the competitive edge never left him. He set his sights on creating an all new sport, he said with usual bombast, something that would “make a name for India… a game born in India that will be the pride of India’s sports identity”.

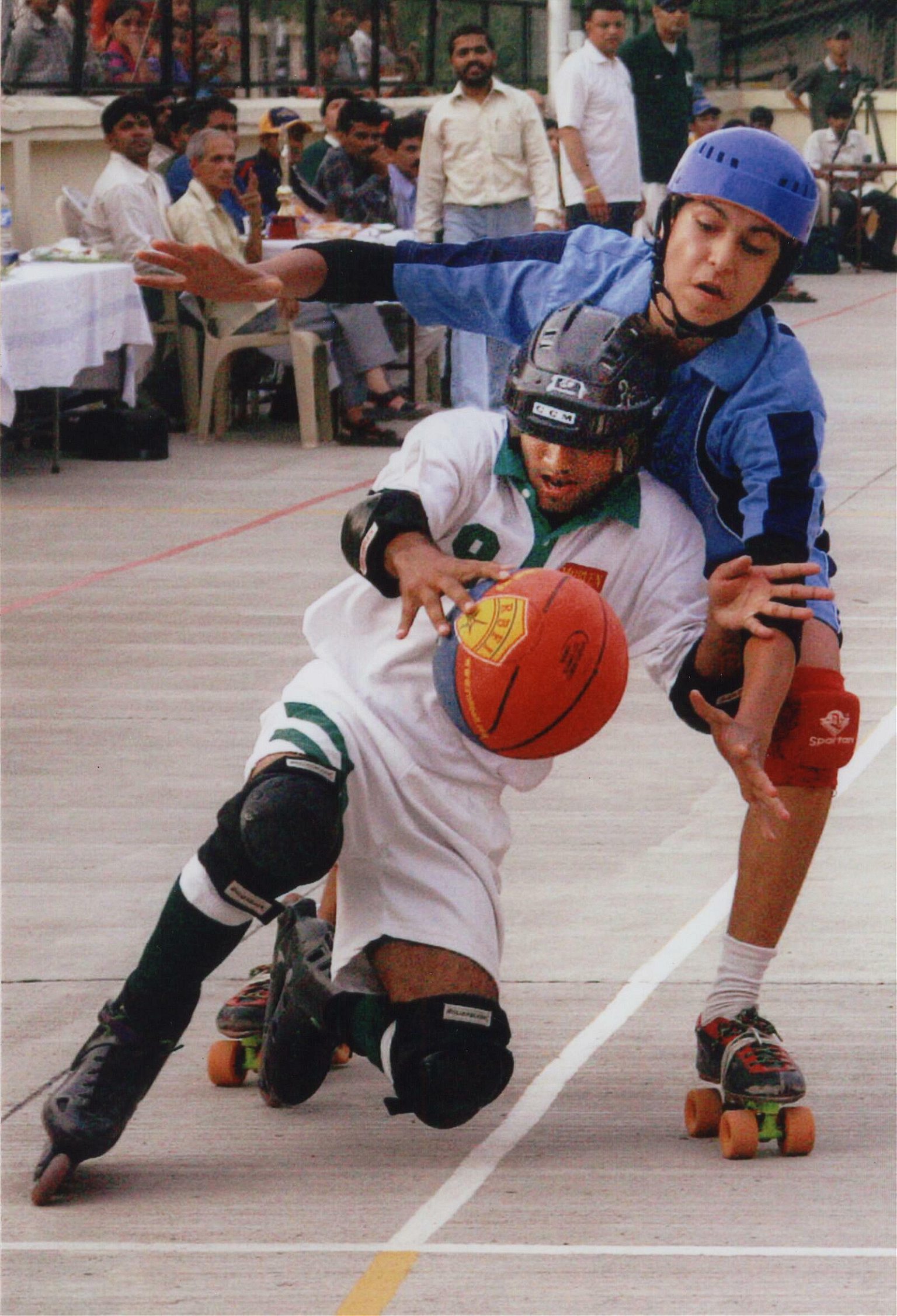

The idea for roll ball came to him one afternoon in 2003 when an errant basketball interrupted his skating instruction. Roller skating on old school quads is still popular in India and ball sports are always well liked. So he decided to combine the two. The result is hard to visualize for the un-initiated. Two teams of six players each whiz around an outdoor basketball court on roller skates, slowing only to dribble, pass and launch a basketball-like ball into a hockey-like goal.

At first Dabhade’s roller skating students thought it was just another training exercise. Almost a decade later many of them competed in the first Roll Ball World Cup held in Pune in 2011, an event with its own mascot and teams from 17 countries. College students now, almost all in engineering, his original students remain fiercely loyal to the sport and their former teacher.

Two of them, Kashyap Raibagi and Nikhil Oswal, showed me around when Mehta was busy. While they were more interested in taking me to tea shops and restaurants, I managed to talk them into doing the roll ball court tour one afternoon. Our first stop was an outdoor basketball court surrounded by apartment buildings. We sat on a set of bleachers and waited. Slowly, middle school aged girls began to trickle onto the court, strapping on helmets, knee pads and skates. They dribbled the ball and passed and sped up and down the court, spinning to change directions and sometimes even before launching the ball into one of the goals. A man who appeared to be their coach called out instructions.

After a while a group of smaller children took the court, skating this time without a ball. It was informal and hard to follow and I had trouble understanding if the children belonged to a school, a club or some other sort of organization.

NOTHING ABOUT THE SPORT HAD BEEN LEFT TO CHANCE

Everything about roll ball seemed random until I heard from Dabhade himself. Nothing about the sport had been left to chance. Before establishing roll ball he studied the history of major sports like basketball and football. In the beginning he worked on promoting the sport on the school level through his fellow educators. Smita Kshirsagar was an early adapter. The principal of a local grade school, Kshirsagar said roll ball “caught like wildfire” with the students.

When I visited her school she showed off a new roll ball court—basically a new slab of concrete. I had come to watch her students play roll ball in a physical education class, but instead was treated to a well-rehearsed cultural performance. It was even more elaborate at the school where Dabhade taught, which put on dances and songs for me while teachers presented me with handmade paintings. They certainly took pride in their hospitality, even if it made it a bit of a challenge to get actual time with the sport of roll ball itself.

Although most Indian players use quads, the sport’s logo shows a player wearing inline skates, more prevalent in western countries. An ice skating version was also in the works and Dabhade was enlarging the goal posts of his sport to accommodate taller European players. It made sense it would happen this way. India is all about adapting and speed. As local business owner and roll ball supporter Vasant Rathi explained, in India “everything is going fast”.

He added: “Through these wheels we can approach all the world now”.

The sport was recognized by the Indian Olympic Association in 2006 and Dabhade met with members of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 2011. By then Dabhade had spread it not only around India, but internationally as well. He used his own money from the sale of his ancestral land to finance trips abroad to introduce the sport and establish teams in places as distant and diverse as Kenya and Belarus. It worked so well that it was a Danish team, and not an Indian team, that won the initial world cup. Anders Reimer, the Dane’s head coach, said it was the combination of several known sports that made roll ball so special.

I hoped I would finally catch a glimpse of this during a state tournament being held just before I left town. I arrived early that morning to find groups of children camped out on the court huddled around sports bags. Like at youth sports tournaments in America, the youth came with snacks and games and waiting mothers. The mothers were sari-clad, sitting in the shade of mango and subabul trees. The athletes had roller skates that looked like they would have been popular in the 1970s. Still this is exactly what I wanted to see, the sport and its athletes in their natural element.

I WAS ASKED TO SMASH THE COCONUT IN THE OPENING CEREMONY

Then I saw the banner: “International Roll Ball Federation Welcomes Ms Katya Cengel, Journalist USA” with a large headshot of me lifted from my website. There were no signs for the tournament, just a banner recognizing my presence. In the beginning I had trouble making contact with anyone in the sport. Now somehow my visit was the main attraction. Fathers stood their children next to me in front of the banner and snapped photos. When the tournament began I was asked to smash the coconut in the opening ceremony. No one informed me it had been pre-cut and I struck it against the ground with all my force.

During the tournament I was seated at a place of honor next to those who had sponsored the event. In front of me was my “Memento” trophy. I smiled and tried to hide behind my notebook. Then the games began and I was enthralled by the speed of the athletes. A player dribbling the ball on the local Pune team crossed one skate over the other to change direction, giving new meaning to the term “crossover dribble”. In front of the goal he passed the ball to a teammate while he tried to find an opening in a wall of defenders. With the ball back in his hands, he made his move, spinning in a tight circle gathering speed before launching the ball into the defenders, only to have it boomerang back. His second, shot-put style heave made it in.

As the Pune team skated backwards on defense, skate-less referees, coaches and newspaper photographers sprinted alongside. At one point a thin boy with knee socks managed to bounce a ball past the renowned Pune defenders to score. As he skated back on defense, he bent his head and placed his hands together in prayerful thanks.

I was finally seeing what it was all about: the speed, the finesse, the fun. More dignified than roller derby, roll ball players earn their bruises from spills, not brawls. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t contact. In the girl’s final a little spitfire on the Pune team was hugged immobile by an opponent after she pushed the ball down court in a fast dribble, squeezed around her opponents and scored six times.

I left not long after the tournament, my bag stuffed with more mementos. My favorite was the roll ball, a kickball-sized red and blue sphere that was deflated to fit in my backpack. They had hoped I prepared to proselytize back in the U.S. I managed to tell a few friends about it, but no one was much interested and the ball was never inflated. It just didn’t seem to translate. The sport has had more luck in other places. In 2013, the second Roll Ball World Cup was held in Kenya. The winners of that tournament? India.