Journalist Annabelle Chapman, serving as election observer, watches as the country continues its westward course after months of turmoil.

On the eve of the elections, rows of ballot boxes are lined up, waiting to be filled. They are made of clear plastic, decorated with only the blue and yellow Ukrainian Trident symbol, as transparent as democracy itself. That seems to be the idea, anyway. As Ukraine prepares to elect a post-revolutionary parliament on October 28, I have returned to Kiev—where I was once based as a reporter—as one of several hundred international observers.

The result is out, the parliamentary elections are being hailed, and a new government is being discussed in Kiev. But as the final votes are cast on Sunday evening, a large part of the story is, in some sense, just beginning. In May, Ukrainians elected Petro Poroshenko as president, replacing Viktor Yanukovych, who fled Kiev in February following mass protests in Independence Square. These early parliamentary elections are a chance to vote out Yanukovych’s political allies and usher in new faces who will push for reform and bring Ukraine closer to the West. In this sense, they are a continuation, if not the culmination, of the protests that rocked the Ukrainian capital last winter.

Observation forms in hand, we’re an enthusiastic group that includes current and retired diplomats, Ukraine-watchers, and members of the diaspora. Many have several missions under their belts, others are completely new. From Kiev, we will be deployed in pairs to election districts and polling stations across the country. It’s a lottery. “Not Crimea again,” two veteran observers moaned during my first mission, for the parliamentary elections in 2012. They would have preferred Donetsk, the stronghold of then-president Viktor Yanukovych. As a result of the Kremlin’s mischief, both are out of bounds this time.

Two days before the vote, the others head off to destinations such as Zaporizhia, Zhytomyr, and Zakarpattia. I get deployed across the river to Kiev’s Left Bank, which has little to do the one in Paris. We whizz across the sparkling Dnipro in our driver’s sports car to take in the terrain. Several times we drive past the Khrushchovka apartment building (named after Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev), where I rented a place back in 2012.

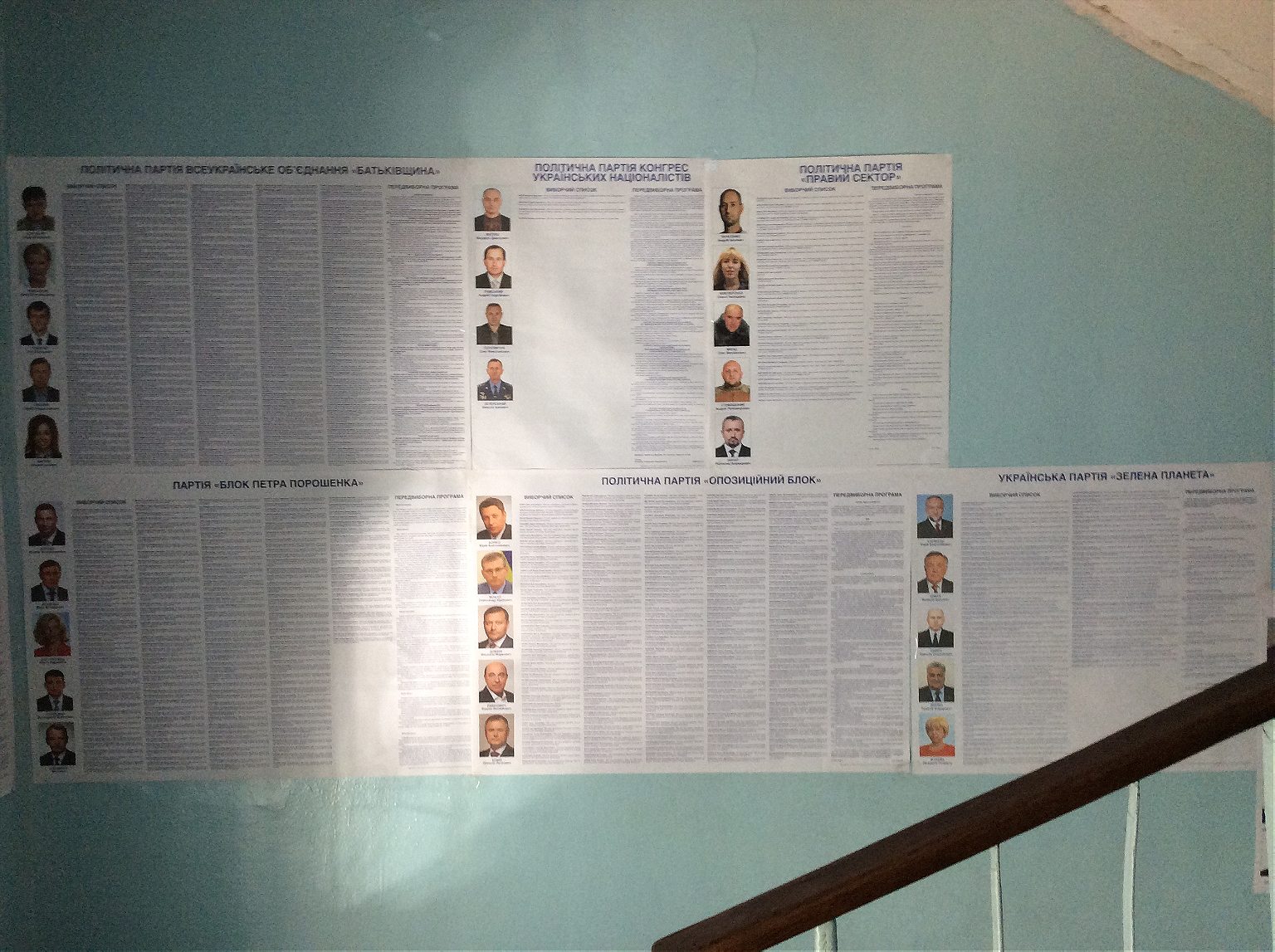

Our tour of the polling stations, many of which are located inside schools, takes us down narrow corridors and through vast shivery hallways illuminated by October sunbeams. Posters with photos and bios of what seems like an endless lists of candidates line the pastel walls. Some candidates look like they really want to be elected, others as if they’re not trying at all. Among them is “Darth Vader,” one of the sixteen candidates with the same name registered to run in these elections, in what has become a standard part of the political landscape here. In one classroom we visit, portraits of the Hetmen, the historic chiefs of the Ukrainian Cossacks, line the top of the wall. “Are these the candidates for the single-member districts?” my observation partner jokes.

Eventually we reach the local election HQ, where the results from the area will be processed after polls close and the votes are counted.

“This is the last day I’m smiling,” a jovial committee member with a pair of vintage sunglasses tucked into his collar tells us in English. He’s referring to the exhausting hours and paperwork that await him and his colleagues after the vote. Wearing gardening gloves, he carries heavy stacks of ballot-papers from one room to another.

Election day is cold and sunny. Voters in padded coats file into the polling stations, where the committee members sit huddled in their outdoor clothes. In each one we visit, we fill out a form asking about the make-up of the electoral committee, how many ballots have been provided, how many people have voted so far, as well as simple “yes” or “no” questions about the way the elections are taking place. Have we, for instance, seen cases of someone being given a ballot paper without the necessary ID, voting more than once or being intimidated? Taken together, these will contribute to the international assessment of the election. Meanwhile, we have been warned not to give comments to the media. I imagine a gentleman from the BBC popping out from one of the blue-and-yellow voting booths, his accent carrying from a mile away.

We’ve got the night shift. After the polls close at eight, the seals on the ballot boxes are broken and the ballots strewn onto a table to be sorted and counted. It’s a lengthy process and we need to be back at HQ by midnight. The committee member with the vintage sunglasses is already there, this time smoking a pipe. In his long coat, worker’s cap, and pointed shoes, he looks like he stepped out of a Bulgakov novel.

The vanilla fumes mingle with the frosty air outside the building and the stars appear. Over the next three hours, the conversation meanders from e-voting (and why it might or might not work here) to the superiority of Ukrainian agricultural produce. Only then do the first results arrive, delivered from the polling stations in person. The first exit polls were released several hours ago, with a clear pro-Western victory, but in election commissions across the country, the work is just beginning.

With its rows of folding chairs made of aged leather, the meeting room resembles a small theatre.

Every time someone in the audience stands up, the seat snaps shut with a clank that makes us all jump. We keep our coats on. “Darth Vader: seventeen,” the chair announces, reading out the first list of results from one of over 70 polling stations. The ballot boxes continue to arrive all night, each accompanied by a policeman. By 6 a.m., the sky outside is turning pink and the line of cardboard boxes and bloodshot eyes stretches all the way down the narrow corridor. An hour later it is light.

Exit polls have given way to preliminary results; a quarter of all the votes have been processed. The winners are already scheduling coalition talks. But for us and the others in this room, the world has shrunk to the size of our electoral district, vaguely delimited by low Soviet-era apartment blocks. Around 8 a.m. my eyes close, but almost immediately the alarm clock on my phone rings and I scramble to turn it off. Another pair of observers takes over and we drive back across the river, watching Kyev enveloped in dazzling autumn light.

Darth Vader earns a handful of votes from each polling station

Evening comes and we are back at our electoral commission. The boxes of ballots continue to pile up against the wall. Darth Vader earns a handful of votes from each polling station, but it no longer strikes me as odd. Out in the hallway, representatives from the polling stations doze against the wall or on their boxes. I’m not sure whether the heating has been turned on or if the corridor is warm from the bodies crowded into a narrow space.

The commission chairman pushes on. Long stretches of intense work give way to objections, deliberation, and “technical breaks,” when people head out into the cold for cigarettes and take longer than expected to return. The sky darkens again. We share jokes and chocolate and fill in another form. Twenty-four hours in, the commission decides to take a break to wash and eat and sleep. When we return that evening, the stack of boxes has almost obscured the Ukrainian Trident high up on the wall.

By now all the polling stations have been processed and the corridor is empty except for a handful of dozing policemen, one of whom has a massive gun on his lap. One committee member has his head buried in a copy of Ukraine’s electoral law. His pipe-smoking, sunglasses-wearing colleague launches into another fishing story. A ringtone starts playing a song by Okean Elzy, the best-know Ukrainian band, and a member of the audience starts singing along. It’s our third midnight here.

Soon the commission members are almost finished and are about ready to fill out the final protocols. That doesn’t sound like much, but it will be another long night, another frosty sunrise before this is over. “Democracy” is a lofty word but it would not be possible—here in Kiev or anywhere else—without the army of women and men who continue working around the clock long after the winners have opened their bottles of champagne.

By bringing in a bunch of new faces (no Darth Vaders among them) and further affirming Ukraine’s westward course, these elections echoed at least some of the spirit of Maidan protests that brought hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians out onto Kiev’s Independence Square last winter. Whether what follows will be enough to avert a Maidan 3.0, and how long for, is another matter.