How the Russian LGBT Sports Federation is trying to hold an event for people who aren’t supposed to exist.

On February 26th, I’ll be at an opening ceremonies event somewhere in Moscow. I don’t know where and I don’t know who else will be there, but I trust my contacts to let me know as soon as I’ve been checked out. Like all participants of the Russian Open Games, I’m to be investigated before I’m given any information. Not for the usual reasons people are investigated in Russia, but in order to keep the games safe from potential saboteurs.

When the so-called “gay propaganda” law came into effect in Russia in the summer of 2013, a time when the marriage equality agenda was gaining traction globally, and particularly in the U.S., Europe, and Australia (same-sex marriage has been legal for more than a decade in Canada, another key part of “the west,” in a cold war context), the international community took notice. The law is nebulous and general, and it was seen by many as evidence of Putin’s—and by extension, Russia’s—refusal to cooperate with the human rights trends taking shape in these countries. This was a problem. The world, after all, was waiting on the Olympic Games.

These Olympics are controversial enough by themselves (Cossack paramilitary beating Pussy Riot with whips, anyone?). And yet, impervious, the law proceeded.

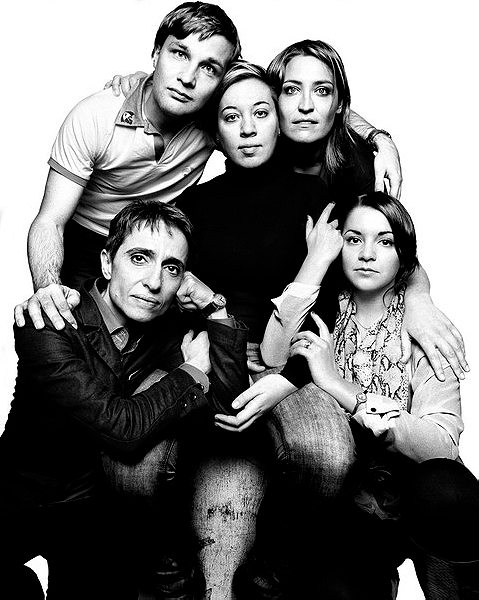

“Life was not so easy before this law,” says Elvina Yuvakaeva when asked about the legislation’s impact, “but the Russian LGBT Sports Federation was a bright example that we could exist at that moment.” Yuvakaeva is a Moscow-based human rights activist and the Federation’s co-President. “We registered in St. Petersburg and in the charter that we must show to be an NGO, you can see that L means lesbian, G means gay, and so on. It says the focus of our work is the LGBT community, so we were recognized as a part of society. We were visible to our government.”

After the Russian State Duma passed the bill banning “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations” among minors, things changed. The law linked homosexuality and pedophilia, and legitimized homophobia as part of the Russian identity. President Putin’s wildly incendiary pre-Olympics message for LGBT people—that they will be safe in Russia as long as they leave children alone—ignited hostilities in an already-violent environment. Incidences of anti-LGBT crimes increased. But so did LGBT visibility. “The law has pushed our agenda,” Yuvakaeva says. “In Russia, society will come to understand.” The LGBT Sports Federation continued, though the Open Games group was forced to add disclaimers to its website, for example, saying that the (completely G-rated) material was only for readers 18 years or older.

One lawmaker suggested that LGBT athletes must be treated as disabled, and have medical support on hand.

Understanding will not come easily, though, and for some Russians, the current situation is all too familiar. “The most terrifying thing about this is, of course, the way they [the State] are going to learn about one’s sexuality. It sounds very Stalin-like, because it might encourage people to get back at those they dislike for some reason.” Yuvakaeva pauses. “Even straight single parents might suffer.” She’s alluding to a second bill brought forth in late 2013 and then tabled, which would open the door to removing the children of people suspected of having “non-traditional” relationships. The common fear is that once the Olympics move out of Russia, and the world’s interest has moved on, the bill—and perhaps others—will move forward again.

But before the Games leave Russia, there will be the Russian Open Games. Scheduled to take advantage of the days between the end of the Olympics and the beginning of the Paralympics—scheduled for March 7-16 in Sochi—when the media are still in the country and Russia is still in the news, the Open Games will welcome LGBT and allied amateur athletes to Moscow. There will be tournaments in eight sports, including futsal (an indoor version of soccer, my sport), and a culture component. But unlike similar events in countries around the world, there will be no public, political demonstration.

At a recent LGBT sports conference in my hometown of Toronto, Canada, Russian LGBT Sport Federation co-President Konstantin Yablotskiy explained why the games are an opportunity for education as much as anything. “When people come together for sport, it shows that the LGBT community is not just bars and sex. It is healthy, and people can accept that.” The Federation’s sensitivity to Russia’s conservative values is entirely intentional. “Our goal or aim was and still is to improve the image of LGBT community,” Yuvakaeva echoes. “Most people have such stereotypes as ‘Oh, gays, they are going to nightclubs and they wear pink pants.’ These Games will be a place to have comfortable tournaments, comfortable surroundings.” Keeping things comfortable is also a strategy to avoid breaking the law.

It remains to be seen whether in practice these distinctions will really matter to ordinary Russians. They make no difference to lawmaker and author of the gay propaganda bill Vitaly Milonov, who recently called on Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin to ban the Open Games, saying that they discriminate against “normal” athletes and that if they go on they must take place behind closed doors. Additionally, he suggested that if only LGBT athletes are included, they must be treated as disabled, and have medical support on hand.

With only a few weeks until the Open Games, registration—particularly by Russians—is lower than hoped. “People are afraid to come to the Open Games because of the situation in Russia,” Yuvakaeva says. “They are afraid to be interviewed by journalists. They are afraid of provocation from homophobic groups, from religious groups. They don’t want to recognize themselves as gays.”

Registrations from Germany, England, France, the U.S., Holland, Canada, and Kazakhstan hint at international support for the Games and the Federation, but Yuvakaeva insists that local participation is far more important. “Our idea was to bring as many people [as we could] from all over the country. In St. Petersburg and Moscow the situation is okay, but if we are paying attention to everyone we have to look at the small cities. The homophobia is very bad. If you live in a small city it is almost impossible to hide.”

It might be easier to hide in the capital city of Moscow than in Mendeleyevsk, but it’s still Russia. In 2012, the Federation organized a Winter Games event in Moscow Region, but after the local mayor received an anonymous letter threatening violence, the organizers lost their venues. “They didn’t want problems,” Yuvakaeva says. “It was easier to cancel the event than to protect us from homophobic people.” Ultimately, the Games went on in an alternate location, but the organizers learned from the incident. Threats to security can come from without, but also from within.

For the 2014 Open Games, there will be bodyguards. Volunteers will patrol with walkie-talkies, and every participant will be vetted before they are registered and given their access passes. “So, it is not really the Open Games,” Yuvakaeva says. “We would like it [to be], but it’s not.”