French winemaker Jean-Marc Brignot relocated to a former penal colony in the Sea of Japan for a simple reason: he wanted to be free.

So there we are, in the kura—interior storeroom—of the partially renovated space that will soon become Sado Island’s first wine bar, Barque de Dionysus.

The bar is just one of Jean-Marc Brignot’s many ambitious projects on this outpost some 20 miles off of Japan’s west coast. He is a vintner, a raconteur, an exile of sorts, and the meal with Brignot tonight has a unusual rhythm to it: we take frequent breaks from eating and drinking to wander outside and stare at the ocean. A storm is rolling in. You can’t avoid nature on Sado, it is always in your face—sea, forest, and mountain all merge together. After a moment’s reflection, we turn our back to the storm, go back inside, and eat more of the huge wheel of Comte he has just brought back from France.

Wine was what brought me to Sado in the first place. The Swedish magazine Fool had written about Brignot, turning the profile of the winemaker from Jura, France into a Manga comic. It was a suitably exotic treatment for a very rare vintner. In the natural wine world, and in France in particular, Brignot had acquired a certain unconventional reputation.

Brignot’s wines are lately so impossibly hard to find they are a kind of unicorn amongst collectors

His wines are highly acclaimed, rigorously natural, and lately so impossibly hard to find they are a kind of unicorn amongst collectors. His style of winemaking in France eschewed modern techniques in every part of the production process—from utilizing biodynamically farmed fruit to employing a hand-cranked press to crush grapes. It’s what sets him and other acolytes of ancient winemaking techniques apart from their counterparts who embrace modern technology as a way to hone and improve on generations of winemaking tradition. “Natural winemaking”, for those who practice it, is a way of life and takes on the significance of a higher calling. It also tends to piss off those who do not fit into this tiny subset of producers, who feel themselves no less in touch with the land than their more outspoken counterparts, and bristle at being somehow “unnatural” by comparison.

So why did this traditionalist abandon his home to come to a country with virtually no winemaking tradition? It’s an apparent insanity: a year and a half ago, he walked away from France, his business, and his colleagues just as his acclaim was peaking in order to plant grapes and—eventually—make wine on this remote island in the Sea of Japan. His wife is Japanese, yes, but she is not from Sado. Brignot, with his wild moplet of hair and dancing eyes, seems like the kind of person who would know something about making wine here that the rest of us don’t. Maybe this is a place where something truly magical can happen between the grapes and the soil and the sea?

It would be a surprise if so. Commercial domestic wine production in Japan is young, only around 50 years old, and most of what was produced would not meet international export standards. Before arriving in Sado, I visited a very high-end winery in the Kyoto prefecture (a passion project by a wealthy collector) and sampled wines from regions around Japan. The best way to describe most of it is inconsistent–some is good, most sits firmly in the realm of decent, and a few were borderline unpalatable. At least in what I tasted, there was nothing on par with consistent low-cost producers from Chile and Argentina, and most price points in Japan were much higher. Moreover, for all the recent popularity of imported wine in Japan, it is still very much a beer country, with commercial and craft brews making up roughly half its alcohol market, according the USDA. Japanese have a long way to go before they even come close to the type of consumption levels one might find in the West.

It should be said, however, that Sado is no ordinary island. Mention Sado to most people on mainland Japan and while its existence registers, only one person I met in my travels had ever been. And even that was only during the summer for an annual music festival put on by the Kodo drummers, a famous Taiko drumming troupe based on the island. Visitors rarely come during the colder months. The Sea of Japan can go from welcoming to unforgiving quickly. When the passes close due to snow, the Japanese Defense Forces that are housed on the island literally barricade themselves on the mountain like dwarves in a Tolkien novel.

Sado became a place synonymous with dissent and free thinking

Historically, Sado was known primarily for two things: its massive gold mine and a penal colony. The latter seems to have shaped the population of modern Sado in the most profound way.

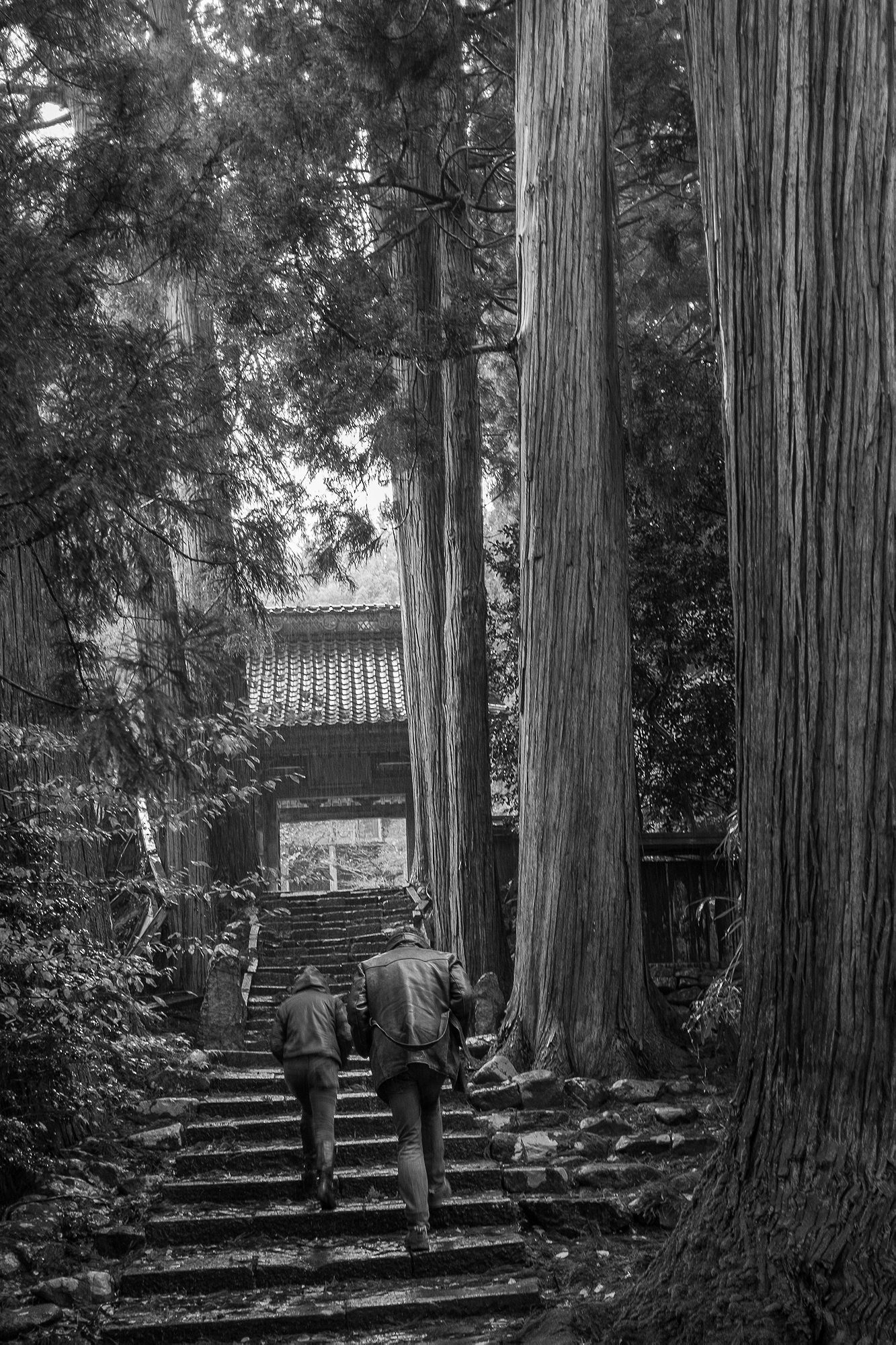

Over the course of centuries, Sado became a place synonymous with dissent and free thinking—it was, first and foremost, an isolated rock upon which those who disagreed with whomever happened to be in power were exiled. Given Sado’s status as a penal colony for nearly 1000 years, from the 8th century through the 18th, it’s fair to say not all of its early inhabitants were kicked off the mainland purely for political dissent. However, the ones that seem to have most contributed to the abundance of open-mindedness, non-conformity, and creative culture on Sado were poets, Buddhist monks, and Noh theater masters. Their influence can be seen in the ancient temples that dot the island, some mimicking more famous cousins in Kyoto, as well as the fact Sado has a higher percentage of Noh theaters than anywhere else in Japan (roughly one third of the country’s Noh stages are here).

There is a palpable sense of distinction from the mainlanders–a fierce pride in being non-conformist. This is certainly true of Brignot’s fellow expats. There was Marcus, the dreadlocked baker originally from the Bronx with more than 20 years on this remote rock, or Alberto, an Italian actor and classically trained mime who originally came to Sado with the dream of becoming a Kodo drummer. But it’s also true of the Japanese there. Sado is the first place I visited in Japan where people talk openly about personal happiness. This seems like a simple concept, but it is rare to hear Japanese on the mainland talk directly about such things. However, I heard the refrain over and over again from Brignot and others, “happiness is big on Sado.”

While visiting Henjinmokko (which incidentally means “diehard” in Japanese) a butcher shop specializing in, of all things, German sausages, Brignot repeats something I’ve heard from nearly everyone I’ve met here: that the exile experience has shape the Sado sub-culture into something that is, in many ways, quite un-Japanese. The more Brignot talks, the clearer it becomes that whatever led him to Sado had less to do with wine and more with life itself.

Part of it could be just how uncompromising Brignot is. Try talking to him about terroir, for example, and he will insist that there is no correct way to describe the concept. “Shall we fight?” he asks, “because we don’t have a definition of terroir?” The conversation suddenly morphs into one about the orthodoxy and politics of French winemaking. In France, Brignot’s rigorously natural approach (coupled with an outspoken nature) brought him into direct conflict with neighboring winemakers and set the stage for his decision to move to Japan. “If I had been stronger, I would have stayed in France,” he says. “Here, I have an opportunity to make it in a peaceful atmosphere. That has no price.” He feels free to seek on Sado what he describes as “the purity nature can give you.”

It is a gamble on soil, weather, and patience

And, for the first time, he has the opportunity to be a pioneer in a place with no real winemaking history, baggage or orthodoxy. However, that freedom also comes with tremendous uncertainty. He has only just planted grapes, meaning it will be at least five years before there is even anything to taste, let alone age. It is a gamble on soil, weather, and patience; but to Brignot it has become something much larger than just the physical act of agricultural husbandry or fermenting grape juice. On Sado, Brignot tells me, he finally feels like he belongs, something he never truly felt even in his homeland.

It’s my last night on Sado and it’s still raining. We are winding our way up into the mountains on a tiny, single lane road, and I’m wondering if the dime-sized tires on Brignot’s micro-compact will have any traction at all in the mud. I’m also hoping the weather breaks enough that I’m able to catch the 5am ferry back to Niigata and continue my journey further north to Hokkaido. Brignot and his wife Satomi have arranged a unique dinner as a farewell—we are heading to Restaurant Seisuki, which boasts only one table. It’s run by Osaki Kuniaki, who trained at Michelin-starred restaurants in Europe and before going on to become a successful restaurateur with three establishments in Australia. Ten years on, burnt out and ending a relationship, he decided to return to Japan. But like so many others I have met here, happiness and acceptance seem elusive on the mainland. He didn’t return to his native Osaka. He came here.

Inside his home, the storm feels far away. Kuniaki and his wife work in the small kitchen preparing a mix of western and Japanese dishes—seared buri with yuzu chili paste along with fresh baked bread. Brignot has brought a selection of natural wines from a number of his favorite European producers. The talk gravitates once more to why and how people ended up here—freedom and happiness again dominate more than they would in conversations in mainland Japan. Regardless of how Brignot’s wines progress, this talk of freedom, it seems, is the true cultural terroir of Sado. This is the irony of Sado—a former penal colony that now seems to liberate rather than imprison.