A photographer explores Lithuania’s village discos

Andrew Miksys was 25 when he visited Lithuania the first time. He wasn’t expecting much, having stopped in Prague and Budapest—”the cool places of Europe”—on the way. But in Vilnius, he had a deeper experience. Specifically, he met the remaining part of his family, the part that had decided to stay in the Baltics when his grandparents left for the United States after World War II. Nearly two decades after Miksys’ first visit, the photographer has made Lithuania his home. The genius of his work there is to take viewers inside intimate spaces and culture in the country, most notably inside the village discos that serve as social hubs for the new generation of Lithuanian kids. Miksys joined us from Vilnius on a warm Friday night to talk dancing, hookups, and history.

Roads & Kingdoms: What were your first impressions of the country?

Andrew Miksys: My first impressions of Lithuania were kind of mixed. On one side it looked like a place frozen in time. In the villages, some people were living the way they had lived hundreds of years ago: very simple farming and horse buggies. In cities, people looked like they were just waking up from 50 years of Soviet occupation. Not a lot had changed, but you could also feel that big changes were coming and with that there was a lot of uncertainty but also a lot of potential. I stayed for 2 weeks and took a lot of photographs.

R&K: What made you want to go back?

AM: Well there were a lot of emotions with meeting my relatives for the first time. We just connected… A lot of laughing, crying and vodka. Lithuania just seemed like a fascinating place to study and meditate on. It has a very complicated and tragic history—war, occupation, genocide, independence. And I was fascinated with the multi-ethnicity of population. It was just the right combination of things to make me want to come back. In 1998 I received a Fulbright grant, which gave me the opportunity to live here.

Somehow the people just seemed heroic to me.

R&K:: Tell me about your first encounter with the discos.

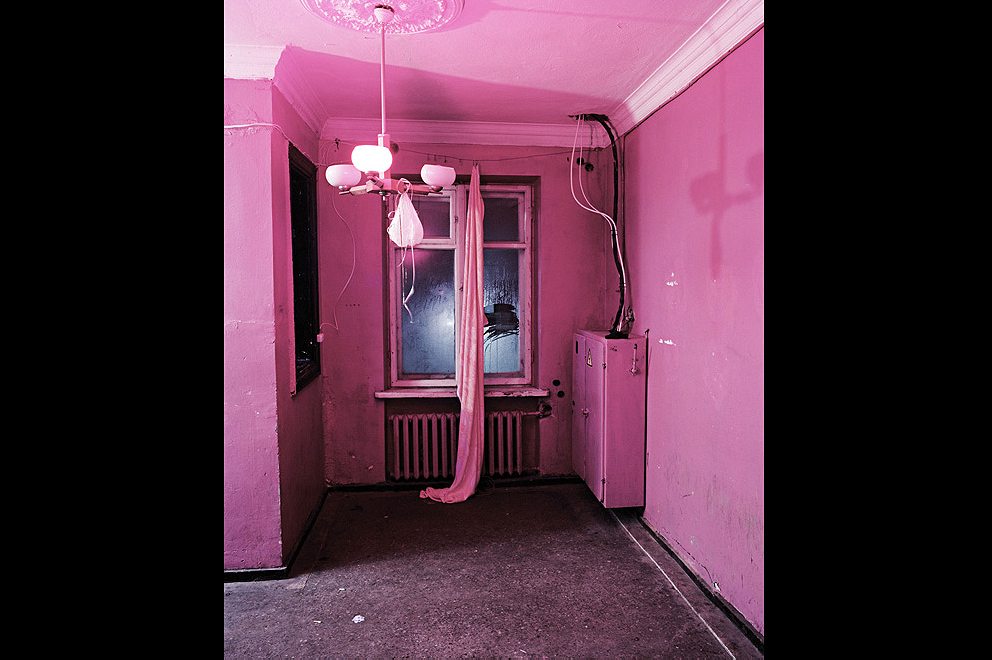

AM: In 2000, a writer friend of mine was working on a project about the last Holocaust survivors in Lithuania and asked me to photography a woman who was the last Jewish person in this village. After the shoot, I went into the center of town to look around. That’s when I saw some teenagers entering a building with loud music playing inside. I followed and found my first disco. It was just a simple room with a disco ball and a Lenin head on the wall. Somehow the people just seemed heroic to me. The discos were places with promise and potential. Maybe you’ll get to dance with a cute girl or boy, meet your friends, get drunk if you want… It’s what I did at school dances when I was a kid. Of course not everything works out. There are fights. You don’t get to dance with the person you wanted to dance with… But there’s always next weekend and the next disco to look forward to.

R&K: What bigger story do you think the discos tell?

AM: I think the best projects leave the door open and don’t necessarily resolve everything for the viewer. I’m not a journalist and I’m not quite sure what documentary photography is. Even though I do projects about specific things—bingo, discos, gypsies—I wouldn’t say my photographs are really about those specific subjects. I’m driven to photograph by strong but rather vague feelings or emotions.

R&K: Tell me about some of the people you met during these parties…

AM: There was a guy in one village who went by the name DJ Playboy. The first night I showed up at his disco, he welcomed me like an old friend, introduced me to people and helped me photograph. He would invite me over for dinner and to the sauna… After a while I felt like a local there, especially in the summer—the nature in rural Lithuania is amazing. People have great gardens with fresh vegetables and there are all kinds of berries in the forest.

There seems to be this strange mix of nationalism and pockets of progressive hip culture for young people

R&K: And you’re making a book about this project…

AM: Yes, there will be 46 photographs. It took me about 10 years from 2000-2010 to complete the project with some breaks in there when I was in the US. I’m a picky editor, so I just kept going until I felt it was complete. I’ve shown the photographs in Lithuania and Berlin, but I’m hoping there will be opportunities to show them elsewhere when the book is finished.

R&K: In the ten that years you roamed the country, did the situation for young people in Lithuania change much?

AM: Joining the European Union in 2004 has helped some, but also caused a lot of displacement as young people left for other countries to find work or to try something different. Many haven’t returned and the population is going down. Today, there seems to be this strange mix of nationalism and pockets of progressive hip culture for young people. It’s difficult to say which side will win.

R&K: Do you divide your time between the US and Lithuania these days? What do you get in one place that the other doesn’t provide?

AM: I spend most of my time in Lithuania. It’s still the most interesting place for me to photograph and there are many unanswered questions to investigate. It’s good for my creativity even though it’s not always the easiest place to live in. I’ve been thinking a lot about living in the US again soon and start a project there. Maybe next year. And I miss Trader Joe’s.

R&K: Do you see yourself in some of these young people?

AM: All portraits are self-portraits, right? In all my projects I seem to focus on individuals and how they deal with their surroundings. Shit ain’t easy for anyone. But I think there is something heroic about the struggle. I like to think that I’m on the side of the people I photograph. In recent weeks I’ve received a lot of criticism in Lithuanian newspapers for showing what some think is a bad side of Lithuania. But I don’t see it that way. I feel like I’m celebrating the people I photograph.

R&K: What are your upcoming projects?

AM: I’ve been photographing in Belarus for the past four years. Fascinating place, amazing, really… The political situation there is quite complicated and it took me a while to figure everything out. I haven’t shown much of this work but I’ve stared a “making of” website for this project: thetulipsproject.com. There are just a few things up there right now, but I’ll be adding more soon (see a preview here).

Help Andrew reach his Kickstarter goal for his book “DISKO: Photographs of Lithuanian village discos” here. Or find more of his work here.