As global temperatures rise, the one winter path into the Himalayan Buddhist kingdom of Zanskar slowly vanishes

The first thing you feel when you fall through a frozen river is frustration. Next panic, when the water soaks through your parka and your fleece layers begin to freeze. Finally, you reach acceptance when you can’t lift yourself up onto the ice, the throbbing in your fingers fades, and your hands no longer seem as if they’re your own. In that moment, you might have a chance for reflection, to consider what villain or foul luck brought you here. For me, the villain was climate change.

We’re all witnessing climate change. The records and charts tell us so. And while for most of us it can seem abstract, an elusive factor in an individual storm or drought, for the people of Zanskar in the Indian Himalayas, climate change is all too tangible. Nowhere more so than on this long ribbon of melting ice, the only winter road out of their remote enclave.

For most of the year the former Buddhist kingdom is cut off from the rest of India by a ring of Himalayan peaks. The isolation reaches back a thousand years when Zanskar broke away from the Tibetan Empire. Ever since, outside rulers have overtaken the broad region that includes Zanskar, but Zanskar and its kingdoms (there are actually two royal lines) have remained relatively cloistered. Only in January and February, the coldest months, the Zanskar River freezes and the people use the ice as a winter road to the rest India.

They call the route the Chadar, which in Hindi means “the blanket,” but in the local dialect translates to the “frozen one.” Five years ago, I joined the annual migration that has taken place unchanged for centuries. The 40-mile hike takes around five days, but it depends on the conditions. Unlike a road on land, the Chadar, made up of sheets of ice, shifts like a moving jigsaw puzzle. A misstep can plunge a traveler beneath a layer so thick that rescuers would have to wait for the summer thaw to fetch the body.

Climate change threatens the whole mythology that exists around the Chadar

Over the last four decades, the average winter temperatures have steadily climbed in the region, making the Chadar ice less and less stable. The year before I arrived, temperatures spiked to 40 degrees and the path melted. One man died and 50 trekkers were left stranded in Zanskar before the Indian army sent helicopters to rescue them. Despite the danger, every year people continue to make the trek. (In the five years since my Zanskar trek, the ice has grown increasingly unstable. A study published more recently by a group of Harvard and University of Massachusetts researchers found that the average Himalayan winter has warmed by 1.75˚ Celsius over the past 25 years, and as a result, “the Himalayas are among the regions most vulnerable to climate change.”)

The escalating physical risks and the practical consequences of a failing link to the outside world comes with an added cultural loss. Climate change threatens the whole mythology that exists around the Chadar. Legend says the deity Sharshok introduced pathfinders to the route at a time when it was solely used by spirits and fairies. Zanskaris believe Sharshok protects travelers on their journeys over the ice. One day when the path completely vanishes, Sharshok and the demons and protectors, the myths and the legends, will vanish too.

Surprisingly, while these losses seem unfortunate to the outsider, Zanskaris seem unfazed by their predicament. Before heading onto the Chadar, I spoke to a monk about how climate change is upturning a number of Zanskar’s cultural fixtures—including the architecture. Summer rain, a new phenomenon to the high desert, is literally melting the mud brick walls of homes and temples.

The newly shaved monk shrugged. “Samsara,” he said. He was talking about the Buddhist attempt to escape the cyclicality of life. The world’s problems are temporary and therefore not his business. On the other hand, local farmers have more immediate concerns rather than fussing about the coming decades. In Ladakh, Zanskar’s closest neighbor, torrential storms tore down the bridges and washed away barley fields the summer before I arrived.

Take a walk on the Chadar. The ice skirts the Zanskar River mostly uninterrupted for the 40-mile length of the Himalayan gorge. The water feeds the Indus, which itself becomes Pakistan’s breadbasket before draining into the Arabian Sea.

From afar the ice looks Windex-blue, but up close it can be so clear that walking feels like levitating over the brown river rocks. The tiny cracks and air bubbles suspended within the ice are the only sign that it’s there at all.

At the same time, there’s something claustrophobic about the Chadar, and the Himalayas in general. There’s no horizon. Like a kid who thinks the moon follows him, here, the mountains are always in front of you, and the height of the granite and sandstone canyon walls make it so you can only go forward or back.

My party, a group of farmers and porters and our guide, Tashi Thundup, a 32-year-old tracker, headed toward Karsha village, the geographic heart of Zanskar and home to an 11th-century Buddhist monastery. The route was smooth enough for them to glide their packs on makeshift sleds.

But on the third day, a blizzard interrupted the journey. It folded us in a blinding, white curtain, and buried the path. It transformed the forlorn beauty into something malicious. The heavy snow weighed on already unstable ice. And the canyon walls became avalanche risks.

We ducked into a cave in the canyon to wait out the storm. Like all the caves in this valley, it had a name–Tip Bao. Travelers have slept here for centuries. Its insides were velvety with soot. We watched the snowfall from behind a low stone berm. Tashi passed around a bottle of Old Monk rum. He dipped his finger in his cup and flicked some rum to the sky.

“For Sharshok,” he said ironically, and downed his shot.

Sharshok had not abandoned us though. Rather, he found us dinner companions. As night turned the canyon blue, a line of travelers approached us from the direction of Karsha. The leader, wearing an army surplus coat, arrived at the cave’s mouth and began to speak to Tashi in Zanskari.

“We need to make room,” he said. “The queen is coming.”

Porters, pilgrims, traders, the ill heading for the hospital, one-by-one, shuffled into the cave. Thirty-people perched around three campfires in the cave. I scanned the flickering shadows for the queen. Traditional Zanskari women wear headdresses stitched with columns of turquoise stones. The queen’s only material signs of royalty were a turquoise and a ruby ring, both set in silver.

She introduced herself as Padma Lamo, the second queen of one of two kings of Zanskar. Her husband’s dynasty had ruled since the time of William the Conqueror. Padma, like many travelers, trekked the Chadar to reach family in Leh. “I’m on my way to visit my 16- and 14-year-old daughters at boarding school,” she told me through Tashi.

The saying goes that if the Woma pass isn’t frozen, the only way to get across ‘is with wings’

Like most people in Zanskar, Padma aligned climate change with the spirits and karma. Before I left, I consulted a local holy woman, and she said the warming temperatures were a result of the people’s spiritual failings. “People have become too materialistic. They go to the monastery to compete with their neighbors. They make extravagant donations so their neighbors will see how much money they have,” she had said. Padma Lamo didn’t have the same worry about materialism, but she too dismissed talk about greenhouse gasses. She was more concerned with bringing schools and clinics to Zanskar.

I asked Padma how the path looked ahead, and she told me that her team had come to a narrow bend in the river, known as Woma, a day-and-a-half’s journey upstream. The saying goes that if the Woma pass isn’t frozen, the only way to get across “is with wings.” The queen’s crew had found Woma but it was four feet underwater, so she waded across. She leveled her hand to her chest: “I’m still damp.”

The others gathered around. They began to speak about the 26-year-old porter named Joldin who had died on the Chadar the previous year. He had been pulling a sled with a rope wrapped around his hand when the sled fell through the ice and dragged him under. It had been the first death since a party of 30 drowned a century ago. He was a friend of a young man named Tanzim Nimbum, also at the fire, who had trekked the Chadar only twice before. Nimbum watched the fire silently as the others speculated about the death.

“They say he went off alone when it happened,” said Tsering Chosjore, the head porter. “And I hear he was running on the ice.”

“A real tragedy,” Tashi said. “He had children too.”

“When I first started trekking the Chadar 12 years ago, the ice was nine or 10 layers deep,” Paljore Khangchang, the cook, chimed in. “You’d fall through one or two layers and there’d still be ice underneath, and the bottom layer was unbreakable. These days, two, three layers maximum.”

The following morning we could not see the ice for the snow, but we heard the rush of the river, a ubiquitous white noise. Only a day earlier, I had barely raised my feet so as not to slip. Now, I was doing a high march to get my heels out of the four-foot snow. We marched single file. At the front, Tashi broke a fresh path. The long line of us matched his gait, landing where his steps had packed the snow. For the followers it took total concentration, like a mimicking game. For the leader, it was a high-stakes game of trial and error, testing the integrity of the ice with each step.

Gradually, as days passed, the gorge walls lost what little slope they had until they stood bluish gray and black, wet from the snow collecting in their grooves.

“Is this Woma?” I asked Tashi.

“This is the start,” he said. The ice slowly retracted to a foot-wide plank frozen along the shear rock above the river. We walked leaning against the rock wall, our gloves slick with its moisture.

And then, suddenly, I was swimming. I don’t remember the sensation of the ice cracking from the wall. I didn’t feel pain—not yet. Water rushed into my boots and under my coat. I watched my fleece gloves soak, then freeze into stiff gauntlets. My hands burned. I was neck deep with no bottom, the current pulling at me.

I looked up at everyone above—at their enormous feet and gaping faces. They had to free up a rope. Buoyed by a pocket of air trapped in my coat, kicking against the current, I started to accept that I would lose fingers. I clapped my hands together and felt nothing. I tried to bite them, even as I was still in the water, to bring them back to life.

Finally, the men dropped a climbing rope and I methodically wrapped it around my wrist. Such a simple task, but so laborious in the freezing water. The crew pulled me and my enormous coat and boots out like a fish on a line. But I still had to climb back up on the ice shelf in frozen clothes and cross the narrow pass.

I tore off the frozen clothes, stood naked in the snow

A porter led me to safety. His name was Lobzang Tsering. He must have been 20 years old. At his own risk of falling in, he guided my feet, which I could no longer feel. It an extreme act of selflessness that I could hardly repay. And when I arrived on the other side of Woma, I tore off the frozen clothes, stood naked in the snow, and with numb hands I pulled on dry clothes from my rucksack. I was lucky not to get frostbite, but the danger no longer seemed abstract.

There was no ceremony when Lobzang left the next day. To thank him I gave him an envelope with most of the money I had on me—about $100. It was the only thing I thought I could offer. I told him to save it for his newborn’s education. Later, I tried to send him checks from the U.S. They were never cashed.

***

We reached a cluster of homes after another three days. They were two-story boxes the color and texture of bread crust. They had small windows with red lintels and bales of hay on their roofs. Between the homes, children played on makeshift skis made from PVC pipes.

“Candy?” one child asked as we passed by.

“Pen?” another asked.

“Chadar?” They said the word for the ice road with reverence. The children were still too young for the journey, but it clearly held meaning to them, as it did for everyone in Zanskar. In the room we rented, the family had tacked photos of themselves grinning madly on the ice.

As we sat in the room, Paljore the cook nursed a cup of tea and told me, “When I was a child, I’d take my father’s goats into the pasture. There were songs I’d sing, a specific one for each activity—milking, feeding, morning, noon and evening. We don’t do that anymore.” He squinted his eyes and remained silent. “I worry about my kids,” he said about his two- and three-year old girls. “They’ll have to leave here to get a good education. And when they come back, what will we have in common?”

I tried to lift his spirits—I told him they’d have all the experiences he’d already been giving them—but soon gave up. Thirty-five years old and one of the oldest members of the team, age had shaken Paljore’s ideas about the world. All the changes and threats that define the 21st century, from globalization to climate change, weighed on him.

While the Chadar melts, another force besides climate change is affecting Zanskar. Development. For almost a decade the Indian army has been laying an artery from the plains in the shadows of the Himalayas to the Chinese border. One of the last sections to be built leads along the gorge walls above the Chadar. The promises are plenty: a year-round road to Zanskar would end the people’s isolation. It would bring new access, and clinch the immediate threat to the Chadar. However, progress has been slow—and deadly. The year before I arrived crews only laid half a mile. Six crewmembers died from rock falls and deadly gales of wind. The army projects that the road will be complete within another three-to-five years and replace the multi-day journey with a five-hour drive. In its way, an inadvertent race is taking place between the failing route of the Chadar and a modern road that is inching through the mountains.

How do you hold onto what you need, let go of what you don’t, and accept what’s coming?

Zankaris, really all of us, find ourselves facing changing weather patterns, rising sea levels, unpredictable storms. In New York, where I live, Hurricane Sandy proved how a confluence of meteorological events can ravage even the most modern city within the course of a single day. The difference, however, is that in the developed world we have the resources to recover and rebuild. Many in the developing world aren’t as lucky. At essence, the question here is over how to face change? How do you hold onto what you need, let go of what you don’t, and accept what’s coming? It’s a question Zanskaris are attempting to answer on a culture-wide scale. And we’ll all be joining them very soon.

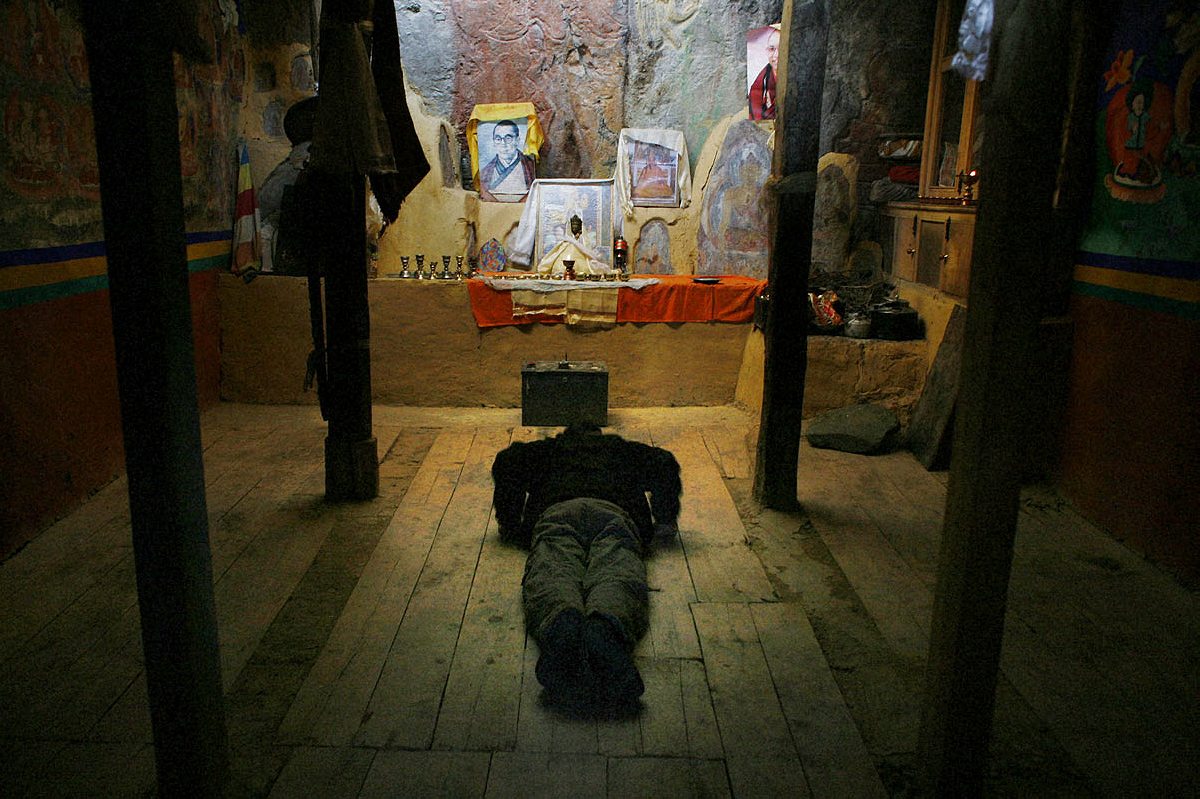

Four days later I passed the garden of boulders at the entrance of Karsha, maneuvered around yaks and donkeys in the dirt streets. I climbed the steps to the multi-tiered Karsha Monastery, with its 80 buildings that grew out of the mountain. I heard the voice of a philosopher monk who piped his teachings into the village using a megaphone, telling people the karmic virtues of living a moral life.

Finally, I stepped into a chamber with a 60-foot Buddha etched into the mountain rock. The etching was at least a thousand years old, and likely a holy site long before the building existed. The outline of the Buddha’s body had once been shaded, but the paint had long dimmed. The rock where his mouth and nose were had crumbled. Instead of peering down at his audience, he looked to the side, almost at what was on its way. He was the Maitreya Buddha, the Buddha of the future.