Balaklava, a small town by the sea in the Crimean Peninsula, was closed to the outside world for more than 30 years because of its top-secret submarine base.

As pro-Western crowds battle police in Kiev to protest President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an EU trade deal, Ukraine’s decades-old struggle with neighboring Russia is spilling onto the streets. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia has resorted to many techniques to keep a firm grip on Ukraine, dividing its population and undermining the Orange Revolution. But the real question is what Ukrainians want for their own future: Russia or the West? One set of answers might be found in the work of photographer Oksana Yushko. She traveled to Balaklava, a small town on the Crimean Peninsula that was closed to the outside world for more than 30 years because of its top-secret submarine base. She spoke with us from her home in Moscow about Ukrainian nostalgia, hollow mountains, and finding a boyfriend on assignment.

Roads & Kingdoms: What were your first impressions of Balaklava?

Oksana Yushko: It’s a very unusual place at first sight. I went there for an assignment for Russian Reporter magazine and then I decided to do a project there. My first impression was that it was depressing, because I couldn’t see the open sea. It’s a closed bay, I didn’t feel free there. People around were open but I felt something in the air. I thought about their past and about their memories and all those feelings made me want to investigate my own childhood during the Soviet era. I decided to do a project about their memories and how they live now, in a place that used to be closed from the whole world.

R&K: What do you mean by closed?

Yushko: During the Soviet era, it was a city that didn’t exist to the outside world. You couldn’t find it on a map. The town was behind the scenes, hidden from the public for more than 30 years because of the submarine base that was there. Lots of them were repaired inside a mountain in the Balaklava bay. Almost the entire population of Balaklava worked at the base. Even family members needed a good reason or proper identification to visit the town. Now it’s open and there’s a museum instead of military factory inside the mountain.

R&K: You got to speak to people who lived there at that time. How did they describe life?

Yushko: People told me that the town was better back then. They were in a privileged zone. It was very prestigious to be in the military during the USSR. They were assured a future.

R&K: How many of them worked in the military?

Yushko: Everyone was connected to the military factory. Some of them served on submarines, some worked at the factory, some of them did something else, but all of them were inside the club.

R&K: Why was this town chosen in particular?

Yushko: It’s a long, long bay that you can’t see from the sea. It’s a very convenient location. The mountain is hollow, so submarines went inside. It was prepared even for nuclear attack.

R&K: What happened when the town opened up to the rest of the world?

Yushko: It opened after the end of the Cold War, but to be honest, I didn’t directly ask people about that because I felt they wouldn’t answer. When I asked about the past, they preferred to change the topic of discussion. Sure, it was a shock to them. The USSR collapsed and that was a difficult time for Crimea. After 1992, the Soviet army was automatically transferred to Russia’s control. It was only in 1997 that the ships and equipment of the Black Sea Fleet were officially divided between the two countries—Russia and Ukraine. And that moment was the most painful for people. They became unwanted. Those who were old enough simply lived off their pensions, but of course it was much less than what they used to earn.

R&K: What does Balaklava mean to you personally?

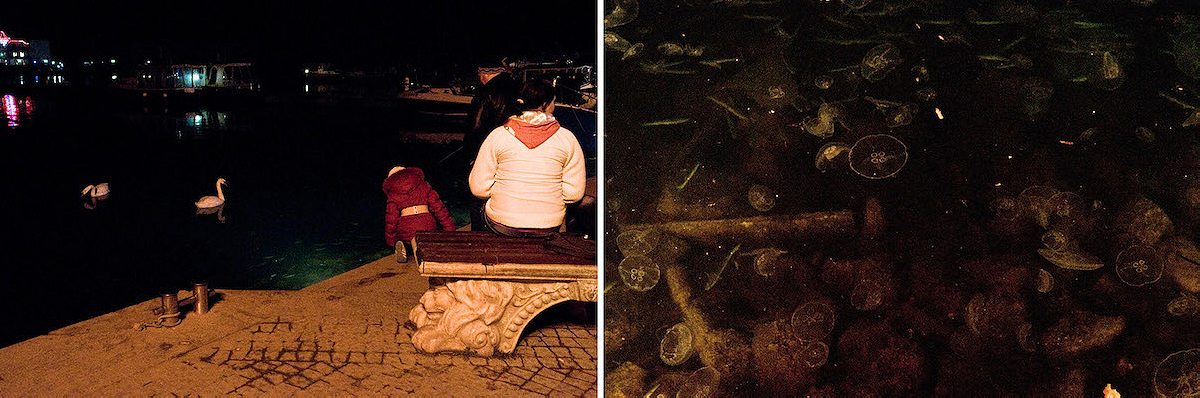

Yushko: I first went in 2010. I was quite successful in shooting, but when I came back to Moscow I lost my pictures. I opened the folder where I had copied them and there was nothing… So that’s where the name of the project comes from—Balaklava: The Lost History. It was like a sign. After that I came back two or three times during two years. My last trip there, in April 2012, changed my personal life. My good friend, who is also a photographer, was shooting near the Black sea at the same time. He came to see me for three days. Now we live together. So Balaklava means a lot to me. Still, I never felt secure there. There is a place near the exit of the bay, a little higher on a mountain where I always tried to go because I could see the open sea from there and I could feel free. In the town, you feel like you’re in a concrete cage. There are remains of barbed wire and you can feel the presence of military guards, as if they’re watching you from the mountains… But maybe it was just my imagination.

R&K: Did it have anything to do with how people welcomed you?

Yushko: People were very welcoming, but I felt like they had limits to what they could tell strangers. I tried talking with fishermen about submarines, but they kept talking about how they lived instead. One thing that was very interesting to me is they weren’t allowed to take photographs in the town. So just imagine, they lived by the sea but didn’t have any pictures of it from their childhood. They liked telling me about the cleanness and the calmness of the town. But if I tried to speak about the military, they would change the topic. I met the ex-captain of a submarine. He talked a lot, but it was more like fairy tales from his military life. People like legends a lot.

R&K: Was it just as hard to take their pictures?

Yushko: Some refused, some agreed only after they trusted me. It was easier with young people. But veterans agreed because they were accustomed to be in the public eye.

In the town, you feel like you’re in a concrete cage

R&K: The town has been open for two decades now. Do they get any outside visitors?

Yushko: That’s changing. They are trying to make it a touristic place. A lot of my friends just come for several hours, enjoy the delicious fish, go sightseeing and leave. There are a few hotels but to me, it’s never felt like a place I wanted to stay.

R&K: How do you think that this strange history changed the people in the town? Do you think it made them paranoid? Nostalgic?

Yushko: Nostalgic, yes. Paranoid – most of them. It’s very sad. I really feel for them, because as I said they became unwanted. I am pacifist and don’t usually like the military, but my feelings about these veterans were different. My grandfather was in the military and the situation in Balaklava makes me sad. In the Soviet Union, everyone was assured about their future because they knew the government would take care of them. Now, people should put trust in themselves more than in the government. Otherwise they will lose.

R&K: You said this project made you investigate your own personal history, can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Yushko: I was born in the USSR in a loving family. My parents gave me everything. I am very grateful for that. But as I was growing up, I was a part of that system. I was very proper. It’s only many years later that I feel I actually became free. In this project, my personal history mixes with these people’s memories. I broke many rules inside me since my childhood and I suppose it is exactly what I wish for people who live in Balaklava. You can change your job if you don’t like it, you can change the city you live in, you can change your life… In the USSR everything was very predictable. And many people just got used to following the flow.