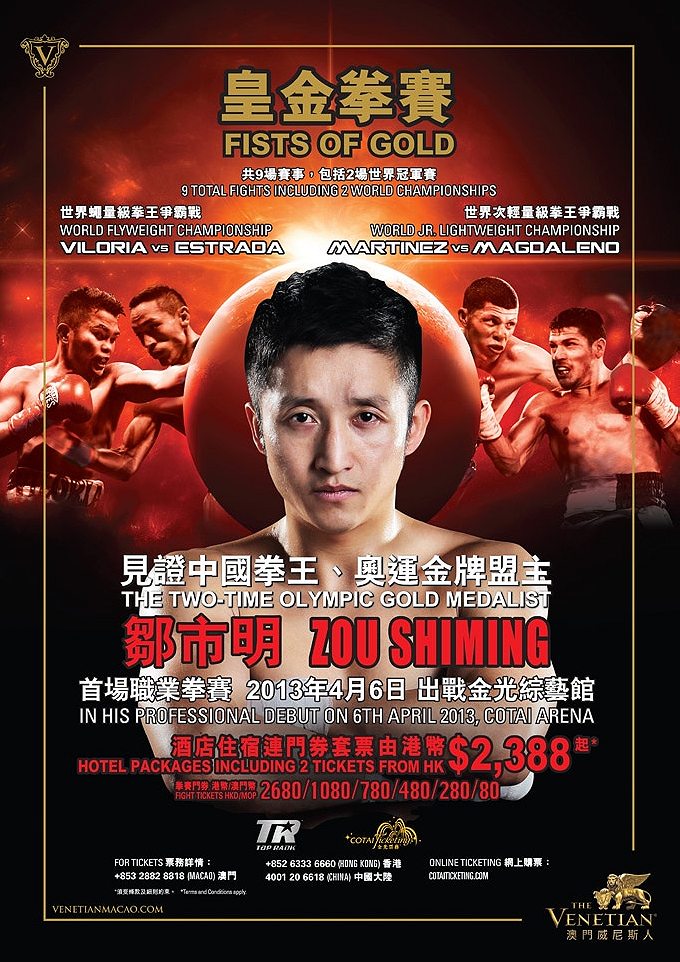

Zou Shiming boxing in Macau: Can China’s premier fighter and a former Portuguese outpost save the sport?

At the podium after April’s multibout boxing extravaganza “Fists of Gold” at Macau’s Venetian, it’s hard to tell who just won the fight. Chinese boxing phenom Zou Shiming easily triumphed in his first professional match, beating a skinny 19-year-old from Mexico on points. But the biggest grin belonged to 81-year-old fight promoter Bob Arum—huge in Vegas but new to Asia—who had just taken a big swing at a far greater target: China and its 1.3 billion people.

An estimated 300 million of those Chinese watched “Fists of Gold” on free broadcasts across China—in addition to American viewers who watched on HBO. That made professional boxing’s first big push into China a resounding success. But as Zou prepares for his second professional fight in “Fists of Gold 2” against another Mexican contender, Jesus Ortega, on Saturday, July 27, the pressure is on. Zou, and the gambling enclave that is hosting him, may be professional boxing’s last best hope. Because no matter the hype, the plight of boxing in the United States is well-known: Fans are fewer, scandals bigger, and paydays smaller. And everywhere is the sense that boxing can neither survive its reputation for brutality nor, ironically, compete with the no-holds-barred Mixed Martial Arts craze.

But the outlook for boxing looks far different in China, in large part because of one man and one island.

First, the man. That Zou Shiming rose to the top of this particular sport seems unlikely. His rise came, as with many Chinese sporting successes, from a combination of talent, determination, and central government planning. Boxing was actually banned under Mao Zedong—it was allowed again in 1986—and the sport only seriously became part of the country’s sporting landscape when its leaders set their sights on hosting the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

They found their champion in the five-foot-five, 110-pound fighter from southwest China. Zou grew up the son of an engineer and kindergarten teacher who taught at the defense industry factory where his father worked in Junyi, famous as the place where Mao first entered politics. Like most of his friends, Zou turned to martial arts at a young age. But he disliked the amount of study involved. “I was impatient and when I found out about boxing I knew it was the sport suited to me because I can just get in the ring and go,” says Zou, as he shifts in his seat, speaking so fast the translator asks him to slow down.

Speed is Zou’s hallmark in the ring, too. His lightning-fast combinations and dazzling foot-speed were what first caught the attention of junior coaches in China. He won bronze at the 2004 Olympics, followed that with two world light-flyweight titles in 2005 and 2007 (adding a third in 2011), and then, in front of the home crowd, won gold in Beijing in 2008. Last year’s Olympics in London saw him win yet another gold medal to cap his amateur career.

He is, in many ways, the Olympic ideal of a Chinese athlete: successful, bankable, and unfailingly polite. He shows up to an interview before his April fight dressed in denim jeans and a leather varsity jacket zipped up to the neck, with only the flash of his golden trainers from under the table hinting at any sense of flair. He was every bit the celebrity in the week before the fight, appearing all over Macau—and across the Pearl River Delta in Hong Kong—through a series of promotional events and workouts with junior boxers, all held to the sound of the tinny techno beats of the “Fists of Gold” tribute song. But when he talks, it’s mostly about how much hard work he has put in since the Olympics, and how much hard work he has ahead of him.

“I am learning every day,” says Zou. “I have to learn how to avoid getting hit. Amateur fights don’t go as long, so you don’t have to worry about that as much. But this fight is a new beginning for me. I have been world champion, Olympic champion, and now I want to be a professional world champion. Ever since I was a child, I wanted to be the best in the world.”

Yet, even in this most individual of sports, Zou puts in a good word for the motherland. “I want to thank China as the country that has supported me, and supported my success in the Olympics. It doesn’t matter where I go, I will always be Chinese.”

His future success may be, in many ways, a joint Sino-American project. Besides being promoted by Arum’s Top Rank Boxing, Zou is being trained by Boxing Hall of Fame trainer Freddie Roach, who has worked with everyone from Julio César Chávez, Jr. to Manny Pacquiao.

Roach is confident about Zou’s viability as a professional—“champion within one year,” he says—but he’s equally voluble about the venue and what it might mean for boxing.

“There used to be Vegas,” he says. “[but] every single casino you go into over here seems to be Vegas on its own… We’ve never seen anything like it and you can see why the sport wants to come here. It needs to come here—there’s just not enough money in the States.”

It took just five years for Macau to take Las Vegas as the world’s gaming capital.

Macau is awash in cash. Not everyone was convinced when the city first opened up its gaming industry to international investment in 2002, but it took just five years for Macau to take Las Vegas’s crown as the gaming capital of the world.

Home to just over 600,000 people, last year Macau welcomed an estimated 28 million visitors while collecting annual takings of more than $38 billion, a year-over-year growth of 13.5 percent and around five times Vegas’ earnings. The growth in its popularity as a destination among mainland Chinese—who come to escape the mainland’s ban on gaming—has begun to worry Beijing. Though travel curbs are rarely officially announced, media have reported numerous instances of the central government placing tighter restrictions on how many times people can visit and how much money they can bring when they do.

Loathe to be seen purely as Asia’s gambling capital, the Macau government—and the owners of Macau’s massive “integrated resort” developments who are at pains to please their overlords—are quick to emphasize everything else the city has to offer. Hence the stream of Asian pop stars and the hosting of such sporting events as its annual Formula One Grand Prix weekend and now, Fists of Gold.

Like Vegas before it, however, Macau has had a tough time distancing itself from its shady past. Administered by the Portuguese for more than 400 years, the city reverted to Chinese control in 1999, a move that was preceded by a fierce turf war between the triad gangs that had long plundered the city and run lucrative gambling operations and prostitution rings. And while Macau’s leaders claim those wild days are long gone, all it took was the December release of Wan Kuok-koi after 13 years in prison (for multiple offenses, including loan-sharking and attempted murder) to bring the bad memories flooding back. “Broken Tooth”, as Wan is more commonly known, had been the very public face of Macau’s seedy side in the run-up to the 1999 handover, brazenly defying the police and his rival triad leaders.

It’s just another reminder that the path to boxing success in the Middle Kingdom is far from assured. Plenty of sports are trying to win over the Chinese market—even hockey is trying to establish a foothold there. But it’s one thing for millions of Chinese to tune in and cheer for Zou because he’s Chinese. It would be another if they simply rooted for him because they are boxing fans and he is a superb fighter. A truer test of the appeal of international boxing in China will come in November, when Arum’s company will stage a Macau fight between Manny Pacquiao and American Brandon Rios. Success will hinge both on good marketing and good behavior—no scandals, staying clear of the triads. And yet, the potential rewards are clear.

“If it is done right,” Arum says on the podium, still aglow, “this will be the premier audience for the sport of boxing in the world.”