A European paean to an American idea, passed from generation to generation, lives on in Spain half a century after the filming of a classic spaghetti western trilogy.

The show began, as the movies it mimics often do, when a stranger rode into town.

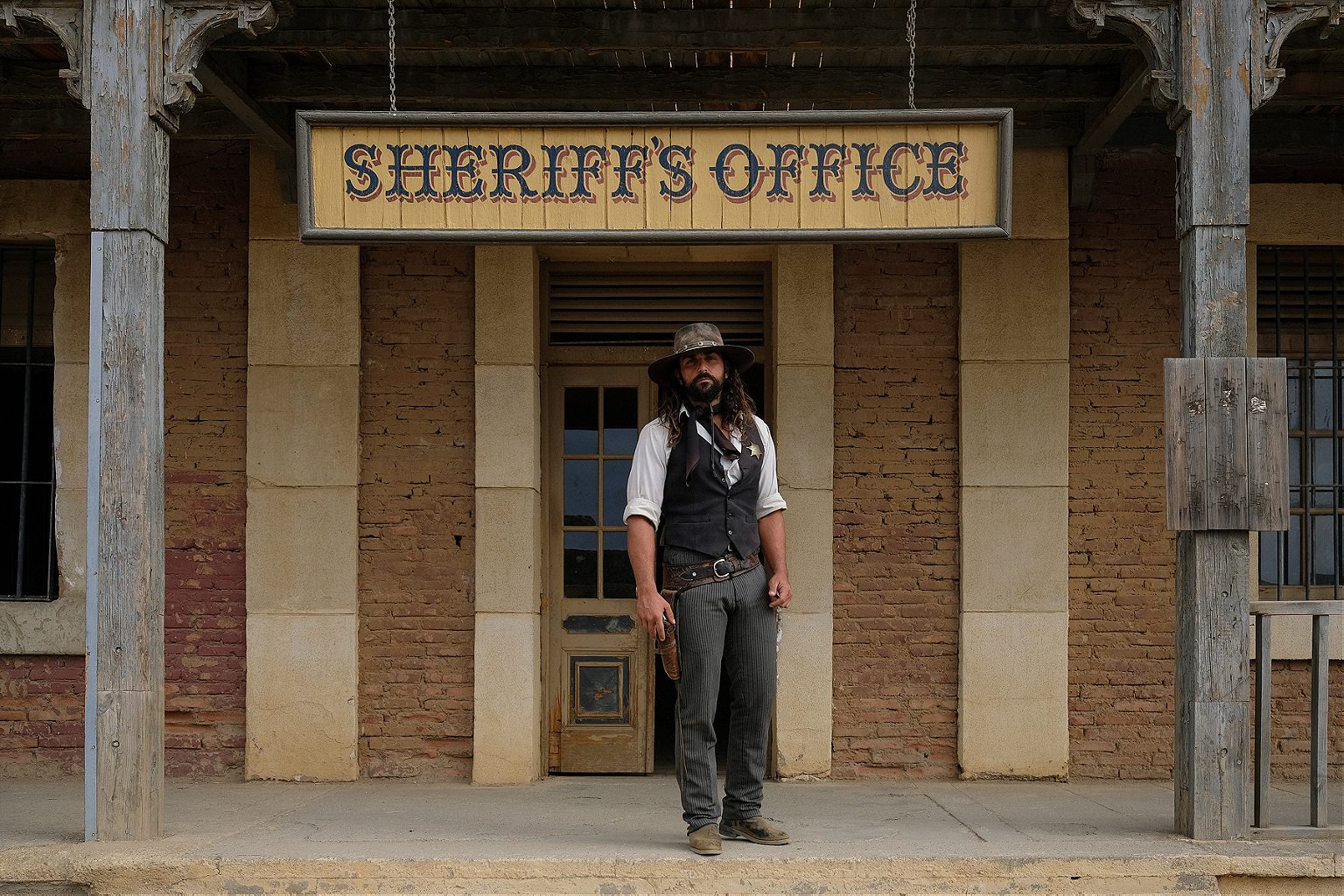

The horses reared, kicking up dust. Punches were thrown, shots fired, insults slung. Three sheriffs stood against three outlaws: dark waistcoats versus khaki duster jackets. A sheriff heaved himself off a balcony onto a bale of hay on the ground. An outlaw swung off his saddle and clung sideways to his galloping horse. Another flailed from the hangman’s noose, and, before going limp, waved goodbye to the tourists who had clustered to watch the shootout from the porches and balconies of the bank, the sheriff’s office, the saloon, and the hotel surrounding the square. Coyote howls and soul-shaking leitmotifs blared from loudspeakers while kids in cowboy costumes shook toy guns at each other. As the gunfire continued, some of the kids laughed, others cried. “Oye! Estamos jugando!” a sheriff yelled. Hey, we’re just playing!

Welcome to Oasys MiniHollywood—a movie set-turned-Wild West theme park in Southern Spain, on the fringe of Europe’s only desert. The Tabernas could be mistaken for New Mexico, Texas or Arizona. For years it was, most famously as the solitary expanse at the heart of the Italian director Sergio Leone’s classic Dollars trilogy: A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For A Few Dollars More (1965), and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966). With their ironic humor, moral ambivalence, and operatic scope, the films not only made Clint Eastwood a poncho-wearing, gun-slinging icon but also came to define the genre known as the spaghetti western. Leone’s Dollars movies were an audacious ode to an America that he had first known through the Hollywood films of his Roman childhood.

The three western-theme amusement parks in the Tabernas desert—Oasys MiniHollywood, Fort Bravo, and Western Leone—are all a short drive from the town of the same name in the province of Almería. In the white-washed village of 4,000 people, a silhouette cut-out of Clint Eastwood hangs on a building in the central plaza. Rumors swirl about the parentage of one resident who bears an uncanny resemblance to the late Henry Fonda, the villain in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Even death here is said to echo the movies.

“You know, there’s a saying that when someone wants to commit suicide in Tabernas, they hang themselves like in the westerns,” said Diego Garcia Sr., one of the originators of the show at Oasys almost two decades ago (he has since retired into a managerial role). He laughed heartily, but his son Diego Jr., 34, said his father was only half joking.

Oasys, which is managed by a hotel group, was originally built as the town of El Paso for the second film in Leone’s Dollars trilogy, For a Few Dollars More. The sets from the movie remain remarkably recognizable. The Saloon Hotel, where Clint Eastwood’s Manco watches Lee Van Cleef’s Colonel Mortimer light a match against the neck stubble of a sputtering bit villain, is now the Yellow Rose Saloon. The El Paso Bank, which was robbed by El Indio’s bandits, is now the First City Bank. In The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, Oasys was both Valverde, where Eli Wallach’s Tuco waits impatiently for Clint Eastwood’s Blondie to shoot him free from the noose after turning him in for bounty, and Sante Fe, where Tuco confronts Blondie for terminating their contract and leaving him stranded in the desert.

For most of the day, the actors at Oasys remain in character for the tourists, posing for photographs, taking families on cart rides, offering western-style makeovers. Alicia Ruiz brings a stoic grace to her role as the high-kicking lead dancer at the saloon, watching protectively over her troupe of university students. In her early forties, Ruiz looks every inch the worldly barmaid who’s outlived any number of foolhardy cowboys. “When we were children, there were only two television networks here in Spain, and every Saturday at noon they would broadcast westerns,” she said. “The culture has a way of creeping into your everyday life.”

Diego Jr.’s childhood was even more closely tied to the cinematic world. “When I was a boy, after my father and the men finished the show, we would have a fiesta at night, and then ride the horses out into the desert,” he recalled. Now, when he can steal some time away on quiet days, he’ll swap his cowboy boots for his trainers and run out into the desert he knows so well, spread out like a frozen ochre sea, techno thumping in his ears.

Surrounded by the Filabres and Alhamilla mountains, the Tabernas Desert receives about 300 days of sunshine and 15 days of rain a year. The desert’s compact 280 kilometers are cut through with choppy waves of badlands and dry riverbeds called Ramblas, a whole world of surreal landscapes all within easy reach of the A-92 highway, connecting Almería to Granada and on to Seville. Cristina Segui, a guide with Malcaminos who runs jeep tours in the area, said that 12 million years ago this was the Mediterranean seafloor. If you squint intensely enough, you can still see the curves of fossilized waves on rock.

Film production began in Almería in 1951, but it was the box-office success of films like Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Cleopatra (1963), and Sergio Leone’s westerns that fueled a movie boom during the 60s and 70s. By 1968, Almería went from being one of Spain ’s least developed regions to having an airport, hotels, and infrastructure that could meet the demands of Hollywood. The Tabernas Desert would continue to serve as a dramatic backdrop for films like Conan the Barbarian (1982) and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) but already by the late 1970s, waning interest in westerns and cheaper competition from countries like Morocco and Turkey had brought Almería’s golden age as the “Hollywood of Europe” to an end.

Rafa Lopez, 52, plays an outlaw in Oasys’ Wild West show and has lived all his life in the Tabernas Desert. As a child, when his father was on the team of construction workers that built Oasys, Lopez lived on site. Now, Rafa is the most veteran of the theme parks’ working showmen. Growing up in that golden age, Lopez had big dreams, but the realities of the film industry eventually got the better of him. Twice in his career, Lopez quit Oasys to pursue acting. When that didn’t work out, he waited tables, worked in construction, and tried a stint at Fort Bravo. Then, ten years back, Spain’s economic crisis forced him back home. “When you’re young, you think you’ll always be young and life is beautiful and you don’t worry about the future,” he said, a living echo of a melancholy Sergio Leone anti-hero. “When you’re my age, every part of your body hurts when you get roughed up. I enjoy my job, but I’ve started to worry.”

The combination of Spain’s debt crisis, which brought down prices, giving generous tax incentives for foreign film producers, and political volatility and conflict in the Middle East and North Africa has once again made Almería’s film industry viable for international producers. Particularly since the filming of Ridley Scott’s Exodus in 2013, the industry has picked up again, with television series like Penny Dreadful and Game of Thrones and films like Assassin’s Creed shooting in the region. Even the giant swaths of greenhouses—Almería’s most important industry—have turned up in the cinema, in the industrial-gothic opening sequences of last year’s Blade Runner 2049. Diego Sr., who worked as a stuntman and horse handler in the movies before joining Oasys, said. “It’s a good time again for cinema in Almería.”

Diego Jr. seems similarly optimistic about the future, an unusual stance for a young person in a country where the unemployment rate hovers around 17 percent. “At Oasys, there’s continuity, and there’s security. In Exodus, I appeared as an extra on a horse next to Christian Bale. Whenever there’s an opportunity to be in the movies, I’ll take it but I’m not waiting for it. I like my job, and I’ll keep doing it for as long as my body lets me.”

As 27-year-old Cristian Navarro, the youngest of Oasys’ showmen, said, he would rather be playing a romantic hero at Oasys than work as a ranch hand or compete at equestrian competitions. “Me siento más realizado aquí,” he said. I feel more realized here.

Though the presence of the American West in Spain is most palpable around Tabernas, Leone’s influence spread well beyond in a scattering of abandoned farmhouses, churches, forts, and battlegrounds that dot the Spanish countryside. One site among them has been resurrected in recent years through pure strength of feeling by a group of diehard Leone fans who dreamed of making their childhood fantasies a reality.

In 1966, in the Mirandilla Valley in the province of Burgos, about 400 miles north of Almería, Sergio Leone loaned several hundred Spanish soldiers from the Franco dictatorship to build a cemetery for the final scene of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. Named Sad Hill Cemetery, it was made to measure for the director’s plaintive vision. The soldiers planted some 5,000 crosses on fake graves, arranged in concentric circles around a paved stone arena where Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, and Eli Wallach faced off in a three-way duel. The same soldiers also built the set of the Batterville prison camp and Langstone Bridge, which they had the honor of blowing up in the movie, set during the American Civil War. They also doubled as extras, swapping their actual uniforms for the blues and grays of the Union and the Confederacy.

When the filming was over, Sad Hill Cemetery was left intact and abandoned. Neighboring townsfolk looted wooden crosses and put those to more practical uses. Over time, the cemetery was reclaimed by nature, buried under seven inches of soil. It was all but forgotten, until 2014, when a group of fans from around Burgos—mostly men who had been turned on to Sergio Leone’s movies by their fathers and grandfathers—formed the Sad Hill Cultural Association with the intention of unearthing the cemetery. They went online to crowdfund the effort; a donation of 15 euros got you, rather macabrely, a grave-marker with your name on it. Fans from all over Europe traveled on weekends with hoes and shovels to assist in the excavation (their efforts were documented in Sad Hill Unearthed by Guillermo de Oliveira, a filmmaker from Madrid). On the 50th anniversary of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, in 2016, about 4,000 people showed up at the cemetery to celebrate. Today, Sad Hill has more than 2,000 crosses, and Sergio Garcia, one of the cultural association’s volunteers, said they’re working on planting more.

On a crisp, sunny afternoon last October, Sergio led a group of primary school students on a hike through some of the sites from The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. He had brought along two friends, Miguel Robles and Sergio Moneo, who would play the bad and the ugly. They had put on costumes and posed obstacles to Sergio (who played Clint Eastwood) and the kids along the trail. Occasionally, the kids were prompted to yell the film’s name in unison, translated into Spanish, of course: “El bueno, el feo y el malo!” One of their teachers—a Sergio Leone fan—had shown them selected scenes from the movie in class; they seemed more interested in lunch.

Hours later, when Sergio and the kids finally reached the cemetery, the three men reenacted the three-way duel—one of the most famous showdowns in cinema—while the film’s soundtrack blared tinnily from a teacher’s phone. The kids were finally roused. They took turns throwing themselves into an open grave, and hanging themselves from the noose dangling from a bare tree above a grave marked “UNKNOWN.”