Where anyone can go out in style.

ACCRA, Ghana—

I almost miss the workshop on a busy coastal road in the Ghanaian capital. The faded sign reading Kane Kwei Coffins in block letters sits prominently outside a small structure set between a three-story supermarket and a few ramshackle buildings. Children run around coffins of all shapes and colors: a chili pepper, a cat, a scorpion.

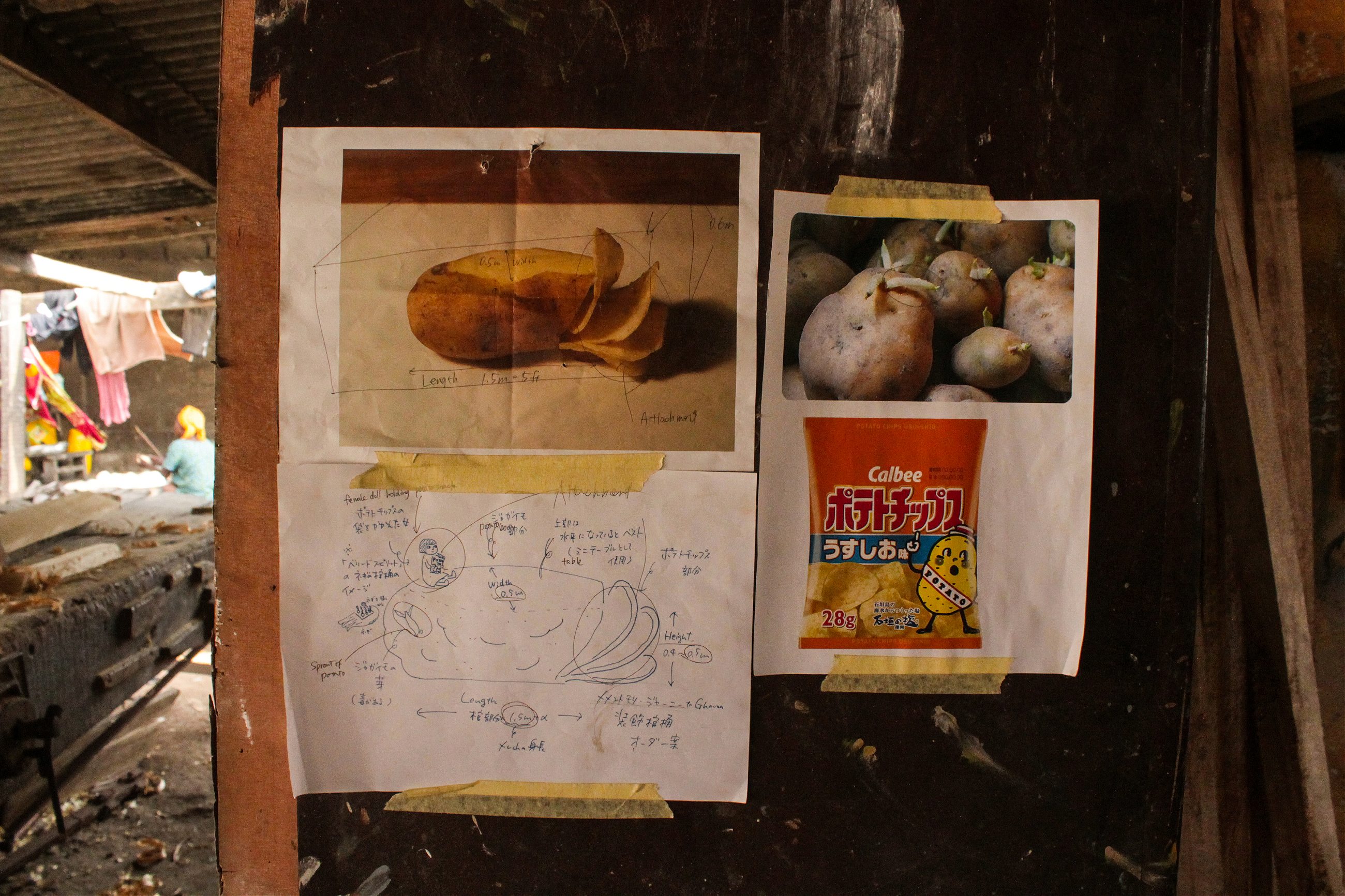

The finished coffins are smooth to the touch, painted in vibrant shades that shine despite the seasonal Harmattan dust coating every surface. Inside the workshop, a group of young apprentices saw grooves into a block of wood that will become a coffin in the shape of a cocoa pod. Founded in the 1950s by Seth Kane Kwei, this is thought to be the oldest coffin shop specializing in abebuu adekai: proverb boxes.

In the last 50 years, these fantasy coffins have become one of Ghana’s most unique cultural exports. The curious tradition of burying people in coffins shaped like everything from lobsters to busty women is primarily practiced in Accra and has spawned over 10 workshops in the capital city. Almost all of these are owned by former apprentices of Kane Kwei, who died in 1992.

Today, six apprentices work at the original workshop alongside Kane Kwei’s son Cedi Anang and grandson Eric Adjetey Anang. The shop produces up to 20 coffins each month. Each year, Kane Kwei ships up to 100 coffins to Ghanaians living abroad, as well as art lovers everywhere from Denmark to Russia.

The coffins intended for burial are made from a soft wood and cost about $700. The ones considered works of art and bound for homes and galleries, are made from mahogany. Those can sell for as much as $3,000. In 2014, a coffin in the shape of a Porsche made by Kane Kwei’s nephew and former assistant Paa Joe set a record for abebuu adekai at London auction house Bonhams when it sold for $9,200.

“When I started working, people used to call me a coffin maker or a carpenter,” says Anang. “Over the years, I’ve become more actively engaged in the design process from start to finish. I think that’s what really helped me transcend just being a carpenter to being a true artist with a vision.”

Despite recent success, the original workshop is under threat. With land prices in the city going up the property is suddenly very valuable, and some of the family want to cash in. Anang is determined to keep it open.

The men who work at the shop are fiercely proud of its legacy. Legend has it that in the 1950s, a traditional leader died shortly after having a litter in the shape of a cocoa pod made. Because the leader died so suddenly, the litter he would be carried in during ceremonies was converted into a coffin to bury him. Seth Kane Kwei, a young carpenter at the time, admired the unique take on a casket.

Shortly afterwards, Kane Kwei’s grandmother died. During her life, she’d had an enduring fascination with airplanes. Recalling how the crowd at the traditional ruler’s funeral had been fascinated by his unique coffin, Kane Kwei built his grandmother a coffin in the shape of an airplane. A few weeks later, a fisherman who’d just lost his father ordered a coffin in the shape of a boat.

In Ghana, a funeral is a celebration as well as a time of sadness. With prestige riding on the size and extravagance of the funeral, family members collect, borrow, and donate money to send their loved ones off to the afterlife in style. Funerals can cost up to a year’s salary.

In one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, the funeral industry is booming, benefitting entrepreneurs including photographers, bartenders, DJs, and professional mourners who will come weep for your loved ones for a fee. While the vast majority of funerals use traditional coffins, abebuu adekai have become a fashionable way to celebrate a death.

Each coffin symbolizes some aspect of the deceased: what they did for a living, their hopes, their vices. Some convey high degrees of respect and honor toward the deceased. A fantasy coffin in the shape of an antelope commemorates a wise person; the eagle is reserved for people of prominence. Fish are very popular designs–the fishing industry is big here–as are Bibles, the only fantasy coffins allowed in churches in this deeply religious country.

London gallerist Jack Bell has argued that abebuu adekai recall the work of celebrated contemporary American artist Jeff Koons. The fantasy coffins play with the idea of scale by spectacularly reimagining objects of the everyday and awarding them near iconic status. As the market for fantasy coffins grows, novelty carpentry is steadily being transformed into contemporary art.

Anang is leading that charge. In 2014, while in Philadelphia, he built a coffin in the shape of a fish and filled it with plastic to address the problem of waste. During a recent trip to the United States, where he was artist-in-residence at the University of Madison–Wisconsin, Anang built a coffin in the shape of a gun to draw attention to the global epidemic of gun violence. The strangest commission the coffin shop has gotten, Anang says, was a coffin shaped like a seahorse for a man from Florida.

Anang has been helping to make the coffins since he was 8 years old. He saw what his grandfather had created and became committed to honoring that legacy, he says: “I chose to work to maintain my grandfather’s story.”

In 2009, Anang’s work was featured in a TV commercial for Coca-Cola–owned sports drink Aquarius. He’s represented Ghana at the Black World Festival in Dakar, Senegal; been invited to Milan Design Week; and his work has appeared in the Royal Ontario Museum.

In Anang’s eyes, the demand for abebuu adekai is on the upswing: “I’m gaining a greater audience, and the demand for the coffins is growing,” he says. Anang has just returned from Kumasi, where he recently signed the lease for a workshop, so that he can expand to Ghana’s second city.

Anang calls me a few days after we first speak to share the good news that he’s just received a grant to go to Saskatchewan, Canada, to collaborate with 20 artists from around the world. This is reason enough to fight the rest of his family to keep the shop open, he says. “It’s a family business—a family legacy. I’m hoping that they can see that.”