Centuries of squalor and imperialism have given gin a bad name. But now, liquor stores are stocked with brands featuring fancy bottles, funky names, and one-of-a-kind botanical blends.

LONDON—

I travel a lot, often slipping off the edge of the map to places barely connected to the outside world. Sometimes, when I come home, I feel that the world I’ve returned to isn’t quite the same one I left. I go away, and Bill Cosby’s the revered elder statesman of family-friendly entertainment. I return and he’s embroiled in a drug and rape scandal. I leave, and Russell Brand’s a prancing prat. I return, and he’s a revolutionary.

It’s not exactly Planet of the Apes, I admit, but cumulatively it’s disquieting, particularly since I never quite know what’ll change next. Take a recent trip to my local off-license—what Brits call a shop that sells booze. This one is popular with hipsters and thus stocked with draft wine and craft ales. As I waited for my payment to clear, I noticed the shop counter was adorned with half a dozen bottles of “London dry gin”—brands I’d never even heard of before; brands with hand-designed labels, funky bottles, unusual names; brands that bore the unmistakeable signs of being hip. Hip? Gin? The world had slipped again.

If you’d asked me to word associate for gin, I’d have started with the Queen Mother, moved through retired colonels in the days of the Raj, and ended with Mother’s Ruin, a common British term for gin dating back to the 18th century, when it occupied the cultural niche later filled by crack cocaine. If pressed, I might remember Winston Smith at the end of George Orwell’s 1984: “Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose.” None of these things are hip. The only person under 30 I could remember drinking gin was someone I met at university who’d take a bottle with her into a hot bath as a form of birth control.

In the Britain I thought I knew, gin came in three forms: Gordon’s was solidly middle-class, Beefeater was squarely proletarian, and Bombay Sapphire was offputtingly posh. All of them were drunk with Schweppes tonic water, some ice, and a slice of lemon. The television personality and bon viveur Clarissa Dickson Wright drank so much gin and tonic over so many years that the quinine built up to toxic levels and damaged her adrenal glands. Fabulous she was; hip she was not. My acquaintances drank Scotch whisky for pleasure and vodka to get wrecked. No one drank gin.

Yet here were Sacred Gin, Little Bird Gin, SW4 Gin, and several others, all glistening in elegantly shaped bottles, their labels bearing cocktail recipes and beautiful logos. Someone was going to have to figure out what was going on here, and I felt I could not shirk that duty.

By 2008, London gin had no more connection to the banks of the Thames than frankfurters have to Germany’s financial center

I scientifically assembled a tasting panel of friends who were free that evening. There was Kate, who works in politics; Rosie, who’s a doctor; Tom, who makes chocolate; and Matt, who works for a cancer charity. The procedure went as follows: Take five glasses, fill each with a measure of gin and a measure of tonic; add ice; drink; rinse; and repeat. It wasn’t very well thought through, as procedures go, in that we all got very fuzzy very quickly. Nonetheless, for as long as I remembered to do so, I manfully recorded everyone’s impressions in a notebook.

Matt, after drinking Sacred: “It sort of hits your mouth sideways.”

Rosie, after drinking SW4: “This is quite addictive, this one.”

Kate, after drinking Little Bird: “I don’t know. They all just taste of gin.”

Gin tastes of gin because of juniper berries, which are the little spherical resin-y fruits of one of Britain’s three native conifer species. In fact—for manufacturers in the European Union anyway—it is the juniper that makes it gin.

In 2008, the EU—which you might have thought had more important things to regulate at the time—went to some trouble to make this point, detailing three categories of the spirit. There’s your bog standard “gin,” which is basically water, mixed with 37.5 percent alcohol, flavored with juniper, and put in a glass. Then there’s “distilled gin,” in which the juniper is distilled together with the alcohol, rather than added as a flavoring at the end. The final category is “London gin,” which can also be known as “London dry gin.” That’s the same as distilled gin, but has less than 0.1 grams of sugar per liter and no colorants.

“They said, ‘This is insane.’ There is nobody in London, the home of London dry gin, who is making this stuff the way it used to be made”

The EU, unperturbed by the continent’s looming financial apocalypse, wasn’t done there. It also decreed that only gin made in the English city of Plymouth could be called Plymouth gin, while gin de Mahon and Vilnius gin must likewise come from their respective bits of Spain and Lithuania. London gin, however, can be from anywhere.

In gin’s 18th-century Mother’s Ruin heyday, about a quarter of London was given over to making bathtub moonshine. But by the time the EU’s regulations were published, London gin was moribund, produced in vast factories with all the character of an oil refinery, almost entirely elsewhere. By 2008, London gin had no more connection to the banks of the Thames than frankfurters have to Germany’s financial center.

But all that was about to change. While the Eurocrats were drawing up their new rules, two friends in West London were trying to break some very old ones.

In one of its many spasmodic bids to clamp down on 18th-and 19th-century illicit distilling (gin inspired rowdiness in the government’s social inferiors, which was clearly unacceptable, plus there were rogue Scotch whisky producers to worry about), the British Parliament in 1823 set a size threshold for spirit stills, below which licenses could be denied, at 400 gallons.

This was not designed to be a prohibition on craft distilling but had become one by long usage. Would-be gin-trepreneurs Fairfax Hall and Sam Galsworthy had worked in the United States, seen what microdistilleries could do, and wanted a bit of that at home. It took them a year to convince the licensing authorities that they wouldn’t ignite a fresh bout of gin-fueled anarchy. But by December 2008, they had permission and started to produce a drink they called Sipsmith out of London’s first new copper still in 189 years. It had a capacity one-sixth of the supposed legal minimum.

“They said, ‘This is insane.’ There is nobody in London, the home of London dry gin, who is making this stuff the way it used to be made, the way it should be made,” explained Zoe Zambakides, who was Sipsmith’s ninth employee when she joined last year. There are now 20.

It is traditional to name stills after women

Like I said, though, the world had slipped while I wasn’t looking. Gin was an idea whose time had come, and Sipsmith acted like a seed in a saturated solution, precipitating crystals of wild juniper-y excitement. Unlike Scotch, gin does not need to be matured, so it can be produced, bottled, and sold with minimal time delay, Within six months, their product was being boosted in national newspapers as the perfect ingredient for a gin and tonic.

Their first still, custom-made in Germany, is called Prudence. It is traditional to name stills after women, and this one was a nod to the term used by the then-Labour government—which famously claimed to have abolished “boom and bust” before presiding over the biggest bust in living memory—to describe its financial policy. Two others (Patience and Constance) have joined her, and the company has moved to larger premises, although still in West London. One evening in early November, Zambakides was showing the new home off to me and 20-odd other enthusiasts, all of us having paid 15 pounds for the privilege.

“The whole point of Sipsmith is about educating people, getting them excited about how great truly excellent gin can be,” she said, by way of an introduction. “But what we make in a year someone like Gordon’s, one of the big brands, makes between 9 and 11 in the morning.”

The London dry contains the extracts of 10 botanicals, including juniper, coriander, orris root, lemon peel, liquorice, and various others, and it tastes warm and round. The stills were warm and round too, copper spheres dimpled all over like golf balls. Their strategic portholes afforded views of the macerating juniper berries, interspersed with rafts of coriander seeds, all floating on an ocean of alcohol. Pipes led up through a bulging neck into a swan-necked tube, which brings the spirit down to points where it can be tapped off.

“If a distiller of the 18th century came to Sipsmith and saw what we do every day, he would not be surprised,” said Zambakides. “This is the old school way of doing it. This is London dry gin.”

To the left of the stills was an alcove where the company’s alchemists create new products. Judging by the blackboard, on Nov. 5, they were working on something called “Damson Chiswick Gin.” To the right was a bar, with bottles on the walls full of experimental concoctions, and shelves full of rivals’ spirits. Britain now has more than 250 craft gins, many like Sipsmith made in London, all of them inspired by this free-spirited spirit, or almost all of them anyway.

As is often the way with ideas whose time has come—the theory of evolution, punk rock, atomic weapons—the idea of reinventing London dry gin in London occurred to two people simultaneously, but there the similarity between their products ends. Ian Hart makes a juniper spirit, Sacred Gin, but if distillers from the 18th century could see him, they would be very surprised indeed.

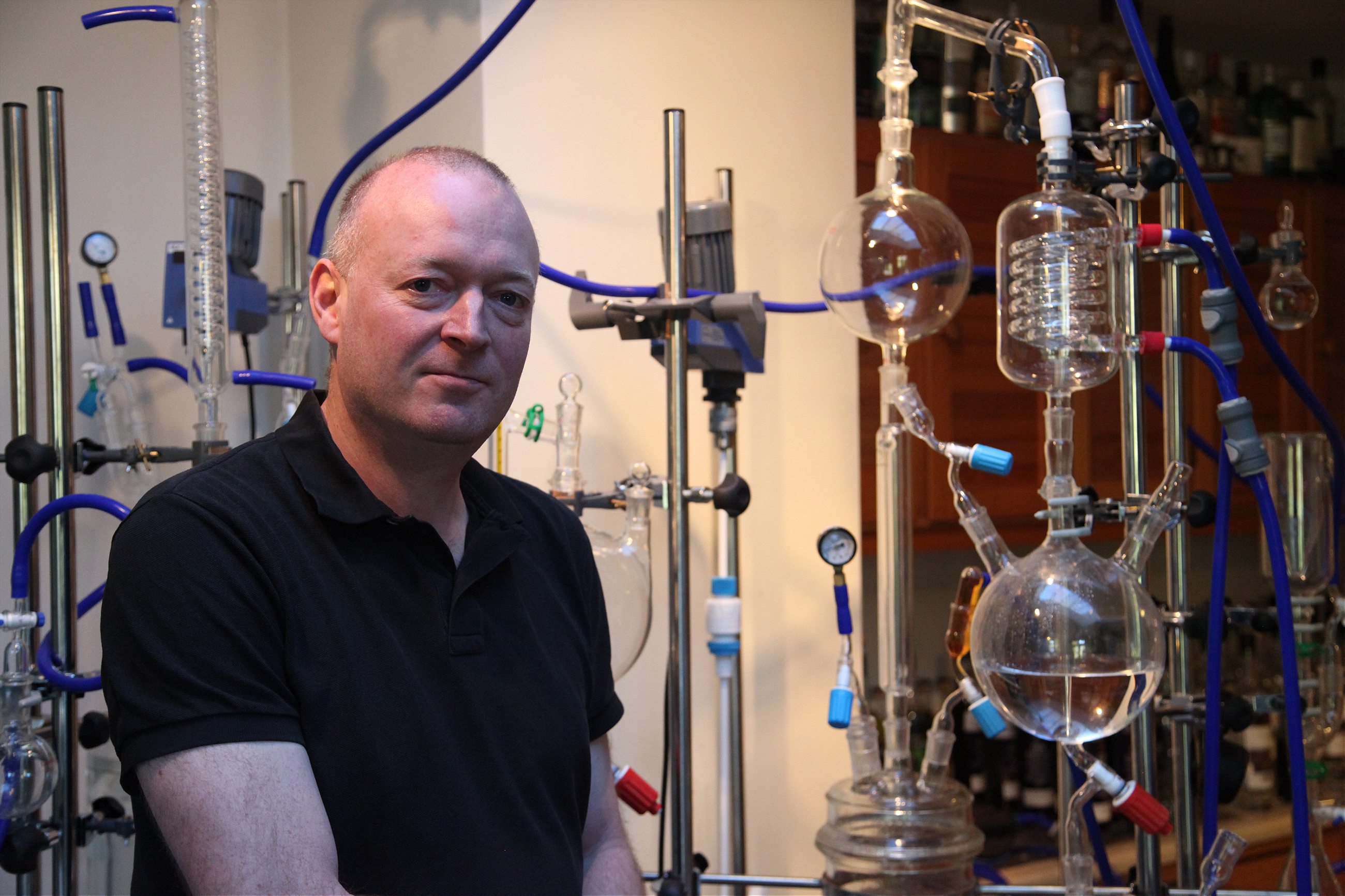

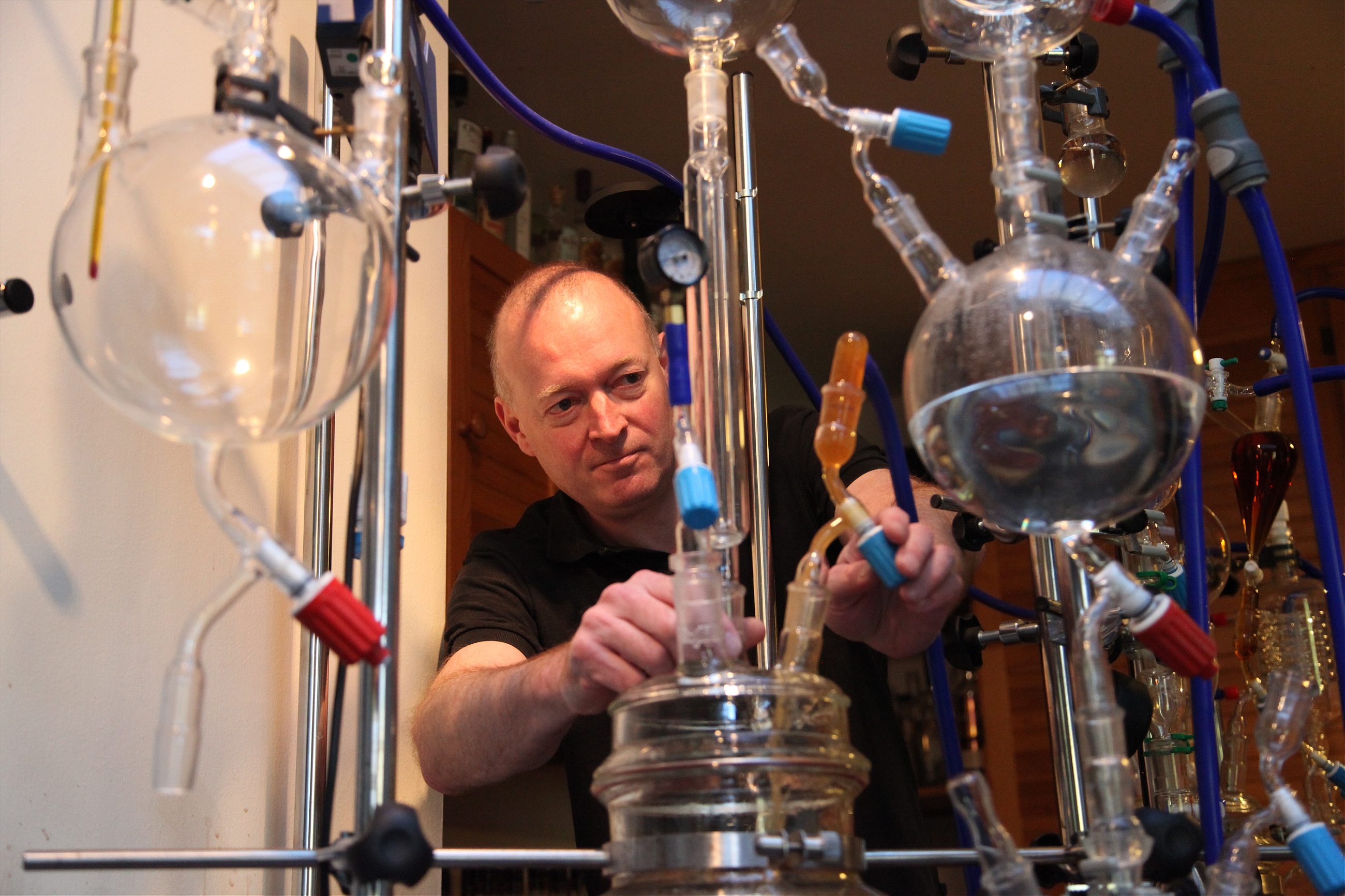

First of all, his premises look nothing like a distillery. It is in an ordinary detached brick house in Highgate, a wealthy district atop a hill overlooking north London. Second, there are no vast copper pots, just an extraordinary contraption of glass and rubber stretching across half his living room. On March 12, 2009, Hart and his business partner, Hilary Witney, gained their own license to make gin, which was the culmination of a long and peculiar process.

Hart had worked as a financial trader and then as a headhunter, but the work dried up in 2006, when the first tremors of crisis started to shake the world’s banks. At a loose end, with a passion for both fine wine and tinkering around with things, he decided to see if he couldn’t improve low-quality Bordeaux.

With the help of a vacuum distillation kit, Hart successfully disassembled wine into four constituent parts: water; alcohol; “a dark red liquor, which doesn’t smell of anything”; and the bouquet, a white frost on a vessel filled with liquid nitrogen. He proved that it was possible to re-engineer wine this way, but it was impossible to make money out of it. What he needed was something of his own, where he could use the same techniques but create a sellable product. That could be gin.

By distilling in a vacuum, he can boil off alcohol and aromatics at room temperature, without cooking them and thus changing their chemical properties (or risking an explosion, which is why he can do it in his living room). After a few unsuccessful experiments the traditional way—adding all the botanicals to the alcohol and distilling them simultaneously—he realized it was easier to distill them separately. That way, he produced a different spirit for each botanical, which he could mix together precisely with a pipette. When he hit on a blend he liked, he took it down to his local to see if anyone else approved.

“I was taking up the latest blend in a stainless steel hip flask and letting staff and friends of the landlord try it,” Hart remembers. “Then one Sunday, the landlord said that it was a great gin. He said if we bottled it, he would buy it.” That was all the encouragement Hart needed.

Watching Hart turn on his distillery was deeply satisfying. If Willy Wonka made gin, it would surely look like this. The vacuum pump was in an old playhouse in the garden, and made a gentle hum. (Another shed in the garden was full of white tubs full of macerating wormwood and various other compounds. A burrowing animal appeared to have been trying to get in.) A tube led from the pump, through the wall, behind the sofa, and plugged into the vast bulbous flasks, which hissed as he turned the taps, sending the pressure down to something akin to that found on the surface of Mars. Water swooshed through blue plastic pipes in to cool or warm the various mixtures, and distillate dripped into side chutes, amid towering glass columns and coils of tubes. Hart had an infectious grin as he manipulated his apparatus.

He produced the first batch of 2,500 bottles of his London dry gin in May 2009, giving out 100 samples to bars he hoped might stock it. One of them ended up in the hands of Alessandro Palazzi, manager at Dukes Bar in London’s West End, and a legend among the city’s cocktail lovers. Palazzi tried it on some regulars, who liked it, and asked for six more bottles. From that day forth, Hart was, in his own unassuming kind of way, made. Palazzi’s martini recipe is printed on the back of the bottle.

“If I wanted to make 300 bottles a day I would probably have to lose the sofa. But that’s 100,000 a year; there’s plenty of capacity. This year we will probably sell 30,000 bottles. Last year we sold 24,000; the year before 18,000,” he said. He smiled, realizing he was describing a neat progression. “The year before that it was probably 12,000.”

Because his gins are a blend, he can vary the flavor as and how he wishes. He sells gins with the cardamom, coriander, and pink grapefruit to the fore, as well as vermouth, rosehip cup, a seasonal Christmas pudding gin (flavored with puddings made to his Auntie Nellie’s recipe), and the classic London dry. My friend Matt was right: Sacred Gin does hit your mouth sideways and is by far the finest gin I’ve ever tasted. Of all the bottles I bought for the tasting, this one got finished first.

Hart exports half of his production, with much of it crossing the Atlantic for the martinis of New York. Of U.K. sales, about half goes to bars, and half goes to retail customers, who can find it in independent wine and spirits shops. Unlike Sipsmith, which is available all over the country, Hart’s gins aren’t in supermarkets; Hart relies on independent retailers to do his marketing for him.

That is one reason why his 30,000 bottles of yearly production, or even Sipsmith’s larger output, is unlikely to be troubling the big producers. In fact, they appear to be relishing the competition, which has made the whole sector cool, even for the previously unhip big three. Bombay Sapphire—the posh one—has opened its factory to visitors who can “choose and book one of our exciting distillery experiences,” which involve a tour of its swooping new greenhouse.

The Gin Guild, a new organization created to unite gin producers, struggled to give me specific figures for the relative sizes of the premium producers compared with the old giants, but it said the sector as a whole is very healthy.

“Gin sales are up 12 percent since 2011, and, according to Nielsen MAT data to the end of November 2013, the U.K. gin category is growing 5.8 percent ahead of the total spirits category,” said Nicholas Cook, the guild’s director general. (I tried to check his figures for myself, but a report from Nielsen costs 1,300 euros ($1,500), so I’m going to take his word for it.)

He also sent me a list of gin distilleries in London, of which there are seven, up from just one in 2008. If you’d like to see some of them and have already done Sipsmith, there’s the giant Beefeater distillery, where you can view exhibits that “help you experience a sensory understanding of the ingredients that make Beefeater Gin,” whatever that means. But in order to do that, you have to trek down to Kennington, way south of the river, which isn’t for everyone.

His distillery marks London dry gin’s true homecoming, since it is the first in decades to open in the city of London

Those keen for a more intimate and more central experience can try Jonathan Clark’s City of London distillery, just up the road from Blackfriars tube station. One of his two copper stills is named Clarissa in honor of Clarissa Dickson Wright, the lady who got quinine poisoning from drinking too much G and T. The other is Jennifer, for Clarissa’s television co-star, Jennifer Paterson. Both are behind armored glass in case of explosion, in full view of the patrons in his bar.

They are copper and round-bellied and produce a spicy, juniper-y London dry that he sells for 32.50 pounds ($49) a bottle—the amount he earned (a week) when he started working as a dishwasher here in the 1970s. He worked his way up until he owned the place. The stills give a ginlike smell to the whole premises, which is welcome on a gray London evening. This is gin making as theater, and—like with Sipsmith—it’s a play he first saw on the other side of the Atlantic.

“I went to New York and saw a bar that had a distillery in it, put my money down for the stills, and went to the city authorities and told them I would open a distillery. They said ‘no’ and gave me two pages of ‘why nots,’ and I worked my way through them,” he said. The armored glass alone cost him 20,000 pounds ($33,265).

His distillery marks London dry gin’s true homecoming, since it is the first in decades to open in the city of London, the square mile of old walled city that stood for centuries before expanding into today’s metropolis. “There used to be 15,000 distilleries in the square mile. Now we are the smallest distillery in the city, also the biggest. The youngest and the oldest,” he said, with a crooked grin.

On Nov. 4, he welcomed Fiona Woolf, the outgoing lord mayor of London, the 686th person to hold one of the oldest elected positions in the world. (Not to be confused with the mayor of London, who is responsible for the whole metropolitan area.) Wearing her full regalia—feather-adorned tricorn hat, dark robe, gold chain—she officially opened the stills.

“As the second female lord mayor, I am always looking out for strong female role models, so I am delighted to make the acquaintance of Clarissa and Jennifer,” she said to appreciative laughter. “It is perfect for the city of London, combining something that is not just relevant but true to our roots, and also a lot of fun.”

I wasn’t sure what she had in mind, since not much else is fun about the city—which exists to help the world’s very richest people become very much richer—but this was a special occasion, so I stood back and drank my G and T without carping. It was a very fine drink indeed.

Clark presented her with a ceremonial bottle of Square Mile, a new kind of gin created for the occasion that contains some yarrow in honor of the new (No. 687) lord mayor, Alan Yarrow. And then she posed for photos with robed members of the Worshipful Company of Distillers, one of the ancient city guilds that once had a lot more members based in London than it does now.

Among her listeners was Cook, director general of the Gin Guild, who said: “There’s probably a distillery opening up once or twice a week somewhere in the U.K. People are recognizing that gin is more interesting than vodka, and instead of drinking a lot, they are drinking quality.”

Personally, I’m not sure why one should exclude the other. I already have a list made up for a new gin tasting, with products from the East London Liquor Company and the London Distillery featuring high, but I’m not sure I’ll have time. Scotland’s finest have just missed out in a contest to be voted best European whiskey. The winner instead was made by the English Whisky Company, at a distillery in Norfolk, just about the least mountainous place in Britain.

Whiskey? English? The world slipped again. I have to run to keep up.

[Cover illustration by Sean Moxley]