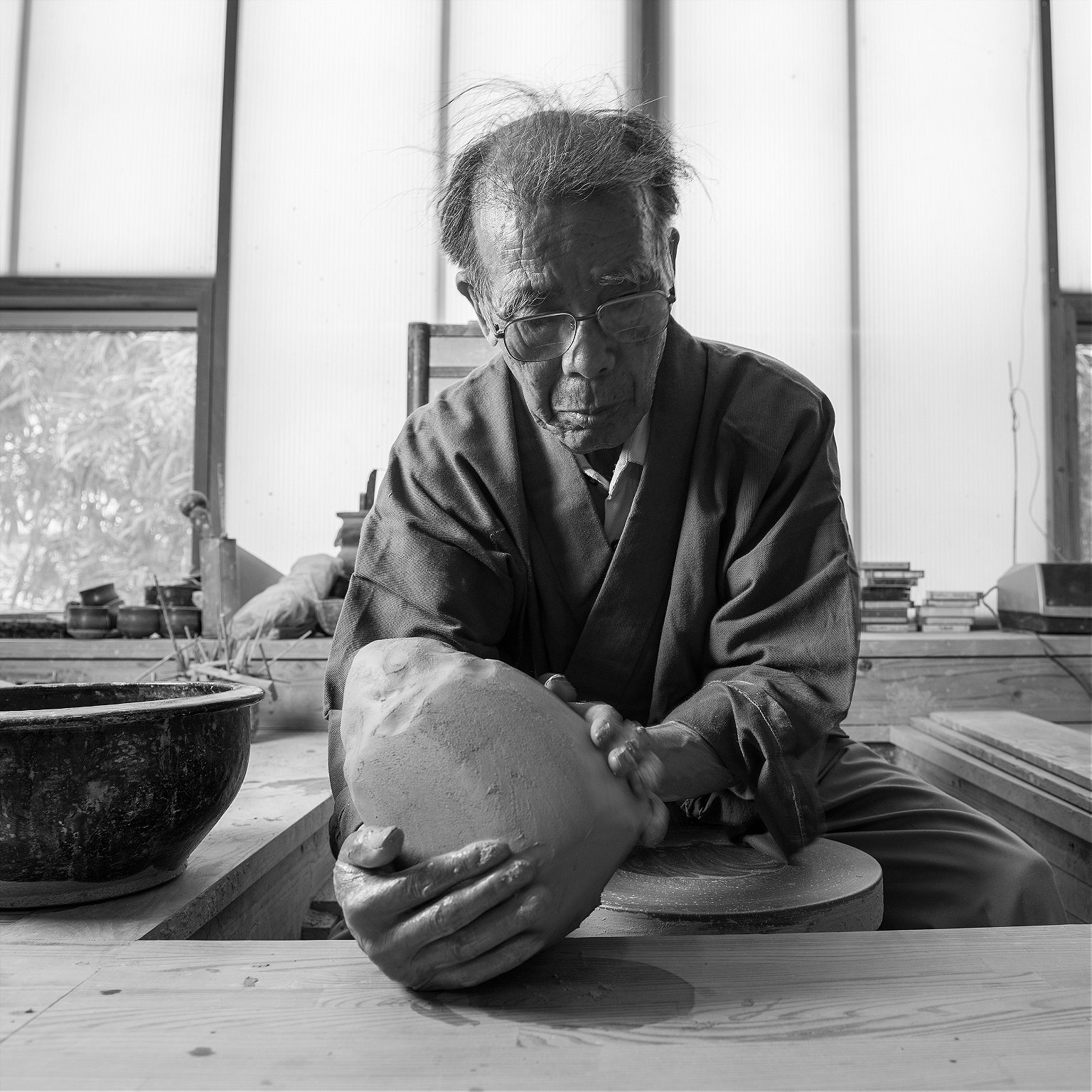

The concept of Shokunin, an artisan deeply and singularly dedicated to his or her craft, is at the core of Japanese culture. But they’re a dying breed.

It all started with a cup of coffee. It was tiny, took 20 minutes to make and cost eight dollars, but still, it was a cup of coffee from Daibo Coffee in Tokyo that planted the seed for Michael Magers’ photography project, Shokunin. Though he had worked as a coffee bean and cocoa trader in a past life, the 39-year-old photographer had never tasted anything that came close to what he was drinking that day. Why? Because that cup of coffee was the result of a lifelong dedication to its perfection, a process that characterizes all of Japan’s master craftsmen, or Shokunin. Magers spent the next months researching and photographing these remarkable artisans, who often work in obscurity and always with an intense, almost meditative focus. His work will be on show at The Terminal in Kyoto from April 4th as a satellite event to the international festival Kyotographie. He met R&K for a cup of coffee in New York.

Roads & Kingdoms: You shot this project over seven weeks in Japan. Tell us about the first Shokunin you photographed.

Michael Magers: There’s a place called Sakai City about 20 minutes outside of Osaka that’s famous for its swordmaking tradition. They make really amazing knives there. I contacted the local prefecture and asked if they could arrange a visit with one of the knifemakers. They said “of course, we’ll take you to the factory.” I showed up there late – it’s Japan, so I already felt horrible – and in typical fashion, there were three people that greeted me and who took me around. We pulled up in someone’s driveway and they said “we’re here, this is the first workshop.” This is where I met Ikeda-san, a blacksmith who looks a bit like Mick Jagger and makes knives for David Bouley and Michael Romano and all these really famous chefs. The space was tiny and I could barely move around. In Sakai, they say the reason why the knives are so good is because it’s not just one guy who does everything, they’ve actually taken the specialization and have broken it down into more specializations, so you have the blacksmith who forges the blade, then it goes to a shaper or sharpener, then there’s a third guy who’s job it is to put the handle on and to engrave it. That’s what he does. He sits like a buddha, putting handles on knifes all day long. I just thought it was amazing that these guys were doing this incredible work that might not get passed down. So the whole idea was to do something that raises a little bit of awareness about this. I was really surprised at the response I got in Japan. People told me they never see this. These guys work in obscurity. Part of being a Shokunin is that you’re doing something for the greater good, that society benefits from this obsessive work that you put in.

R&K: There’s a bit of a spirituality to it, too…

Magers: When you’re around these guys, there’s an incredible sense of peace and focus. They’re like monks. And they’re so in the present. There are old samurai texts that talk about doing the small things right, and letting the bigger things take care of themselves. I started to think about how we have this pyramid inverted in the West, where we tie our happiness and our success to these big picture things and in the end, most people are pretty miserable. To create a thing that’s so perfect as the Shokunin do, you don’t start with the big picture. You start with the small things and you do those things really, really, really well. I thought it was a bit of a metaphor for life itself.

R&K: What does this say about Japan in general?

Magers: Japan is the only place in the world that I’ve ever been where you can have a guy who is still using traditional methods to hand-harvest rice in a small plot by his house and then hop on a bullet train to Tokyo. There’s no place in the world where the traditional and the modern coexist the way they do in Japan. What these guys are wrestling with, and not just Shokunin but all of Japan in some respect, is how that balance will continue moving forward.

R&K: You were yourself practicing your craft, photography, during this project. How did the Shokunin influence your way of thinking about your work?

Magers: It reminded me of the importance of being focused. What I love about photography is that it is the only thing that keeps me 100% in the present when I’m doing it. There can be nothing else I can be focused on, I’m only thinking about what I’m seeing in front of me and how to interpret it. I guess to answer your question, it’s not ingrained in me, I have to remind myself of it, but I did take away a huge amount of learning from them, this idea that it’s okay to focus on doing the small things right. And there’s such a joy to almost everyone of these guys I met, a lightness to them. It can’t be a coincidence. I think a lot of people would look at this and say: how do they not get bored? But it just never came up. Just being around these guys, you feel like you’re transported.

R&K: How were you able to connect with them? I’m guessing they don’t talk much about themselves…

Magers: Not at all, you’re right. They’re not seeking out glory or publicity or anything like that. What was most important to me was the interaction between the man and his work. I really wanted to show who these people were through what they did. Some of them were reluctant to be photographed because photographers had come in to their workshops in the past and had said: “I need you to do X and Y.” A weaver from a legendary kimono house in Kyoto told me he had photographers tell him to stop and pose while he was working. “I said to them, are you going to be responsible for this piece of work that I’m doing for a client when it gets screwed up because I stopped?” So what I basically said is pretend I’m not here.

R&K: Are Shokunin always men?

Magers: I really wanted to find as many women as I could, but there’s not a lot. I think I met five. One of them was a Busshi sculptor, which is really rare. Busshi sculpting is the carving of the Buddha for temples. She actually bristled a little bit about being identified as a Shokunin, she identifies herself as a religious person, someone who’s connected to this deeper Buddhist tradition. It’s quite a spiritual thing for them, they talk to the wood, they coax the wood, they’re telling the wood “I know this is painful but you need to yield to me to give the world the joy that the Buddha will bring to you.” She was an interesting case, her dad died quite young and she took over the workshop under the tutelage of her dad’s most senior craftsman. They run it together.

R&K: So women don’t do this traditionally…

Magers: Not for the most part. Generally if you have a daughter, you would take on your son-in-law as an apprentice. One of the really interesting things is we think of these crafts as monolithic, like there’s a weaver and he weaves kimono. But within that, there are like 10 other specializations that get him to the point where he can weave this thing. There’s the guy that makes the gold thread, and there’s something called sokou, loom-setting, which is basically loading up cartridges with all the thread. That can take a month to do, it’s a seriously labor-intensive, mathematical job. The threads have to be counted perfectly. Historically, this is done by husbands and wives. I photographed a couple who had met as apprentices and had been married 60 years. They were both in their 80s and they talked the entire time. I asked my translator what they were talking about and she said, “oh, they’re arguing.”

R&K: There was one Shokunin who had a particular impact on you…

Magers: I had wanted to photograph Kiyotsugu Nakagawa, who makes oke (wooden buckets) and is a Living National Treasure – Japan designates these people, there’s 30 or 40 of them and they’re all in the crafts space. His wife was sick, so he was dealing with that but I met his son Shuji. He was one of the youngest guys that I photographed, but to me he represents the next generation of Shokunin in that he blends art and craft. He makes these buckets out of 2,000-year-old cedar and he’s exhibited at the Biennale in Venice, in art galleries, but also in restaurants. I photographed Nakagawa-san in his workshop in Shiga. It’s a tiny, incredible space filled with cedar, and we had this amazing connection. A few days later, he was driving around me in his van that smells like cedar and taking me to a guy who makes brushes for shodo (Japanese calligraphy) and then to another guy who’s the last traditional candle-maker in Japan. I never got to photograph his dad, but Shuji and I developed this really great friendship and he invited me to show with him at an exhibition in Paris. He was also one of the curators of the show in Kyoto.

R&K: How did he influence the project?

Magers: I think what he helped me understand that in order for this type of craft to survive and make it to the next generation, for it to be passed on and made relevant, it’s artists who are going to be the torch-bearers. The reason why a lot of Shokunin don’t have apprentices and why a lot of this stuff will slide further into oblivion 15 to 20 years from now, is that kids don’t want to spend 10 years working as apprentices and learning the minutia. Artists tend to be more open to the process and to working through things in a creative manner. There’s a guy for example who’s an indigo dye master and his work has been exhibited at the MoMA. He’s using these techniques that are thousands of years old but finds relevance in the modern world through art.

“Shitsurai” was shown at The Terminal in Kyoto from April 4th to May 6th of 2015 as part of KG+, Kyotographie’s satellite event. For the exhibition, Michael Magers worked with Awagami, a maker of traditional handmade paper in Kyoto, to print his photos on washi. You can see more of his work here.