After completing a powerful investigation within his country’s police force, a Belgian photographer documents life in its prisons.

It was early March 2014 and the Beveren prison, in northern Belgium, was set to open soon. In a final effort to test out its “ultra-modern” facility, the management had invited professionals from the criminal justice system as well as journalists and prison staff to be locked up for the weekend. Photographer Sébastien Van Malleghem was there too. Everyone had a role to play. Some simulated cardiac arrests, suicides or fights in their cells, others had to attack wardens to see how they would react. Despite the claustrophobic, clinical environment, Van Malleghem smiled at the absurdity of it all. The photographer was more than two years into his “Prisons” project, an unflinching look at the incarceration system in Belgium and it was the first time he was seeing a judge scrub the prison floor. In 2013, Van Malleghem had published “Police,” a book that documented the work of law officers throughout the country. Now, he was looking at where the people they arrested were sent. “I wanted to know the conditions of their incarceration,” he says, “in the 21st century and at the heart of Europe.” After an investigation that lasted more than three years, Van Malleghem is now raising funds to publish “Prisons” this summer. He joined us from a suburb of Brussels.

Roads & Kingdoms: Tell me about your first time inside a prison.

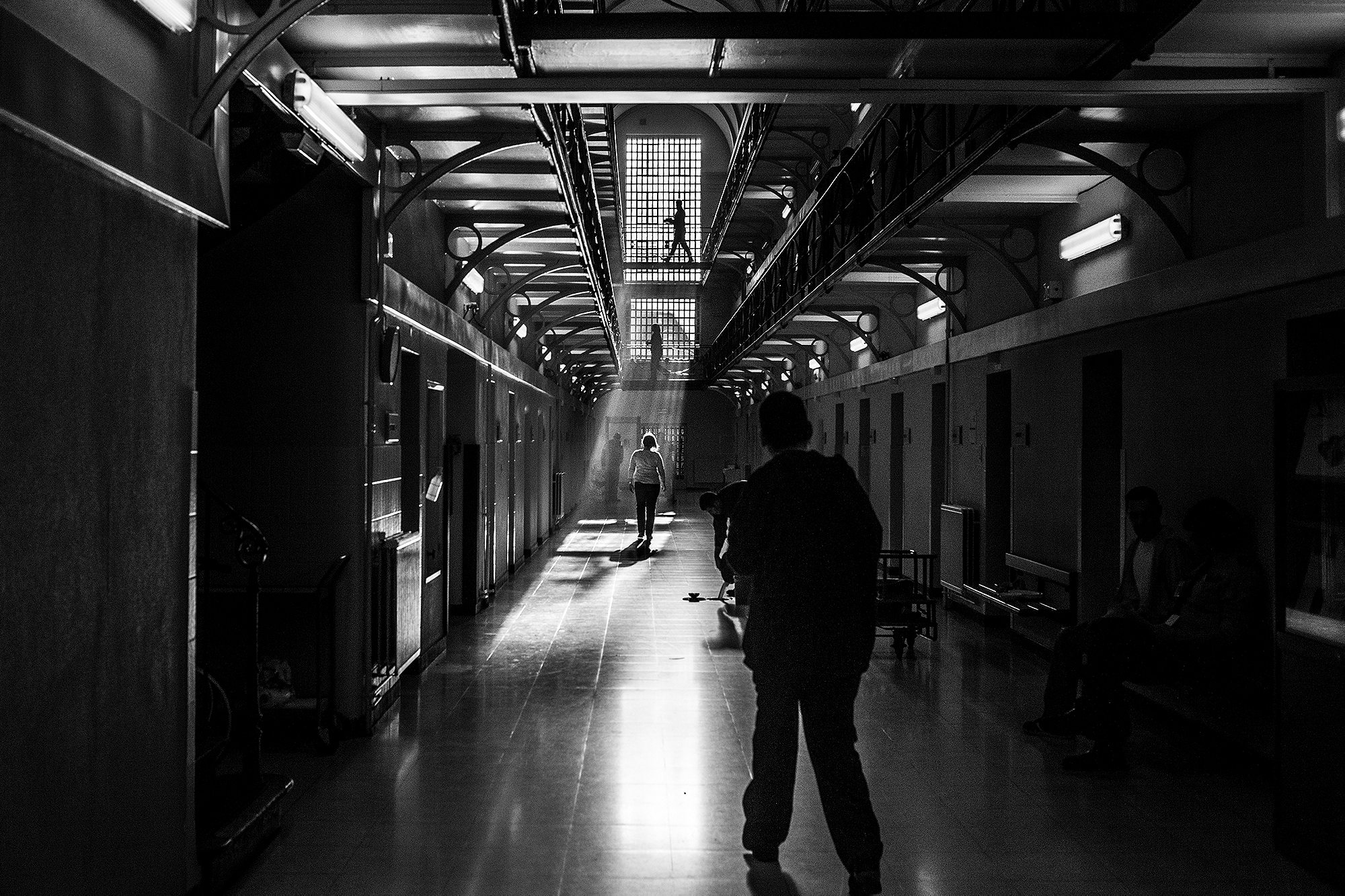

Sébastien Van Malleghem: It was in 2011, in February or March, and it was the prison of Nivelles in the south of Belgium. I didn’t have much apprehension because I hadn’t done a lot of research before going inside. I had read one philosophy book that talked about imprisonment, but I hadn’t filled my brain with images and people and stories. I wanted to be a blank slate so that I could really photograph what I was feeling. The first feeling I had was the one of entering an administrative world. There are doors and fences everywhere, and to get through each one you have to press buttons. There are cameras looking at you, and you just assume there’s someone on the other side. You feel this confinement from the very beginning. Everything is cold, it’s all narrow hallways and straight lines. Your bag is checked, you’re asked why you’re here, the message wasn’t really passed around so you have to explain the project over and over. When I finally got inside, I wasn’t really intimidated, I just saw this as my job and told myself: you’re here, now you have to be sincere.

R&K: How did the inmates react to your presence?

Van Malleghem: There was a lot of suspicion: who are you? Why are you here? What do you represent? Are you a threat? Are you a journalist? I had to break the clichés and explain I wasn’t sent to find a scandal for tomorrow’s paper. What I wanted to know was: what is your job like if you’re a prison guard, and what is your life like if you’re an inmate? People opened up little by little after they saw me coming back. I assume they talked about me among themselves and that helped build trust.

R&K: You photographed 12 prisons, where were they located?

Van Malleghem: Generally, they were outside of cities and pretty isolated. In Brussels, though, because everything is so crammed, the Forest prison and the Berkendael prison are inside the capital. They’re surrounded by houses and people will hear the inmates if they scream in the middle of the night for example. I visited a prison for the mentally disabled near Liège in the south that was surrounded by large green plains. The first small village was six or seven kilometers away. But overall, you feel the same exile no matter where you are. The walls are so high that even if a prison is in the middle of a city, you have no idea what’s going on outside. You don’t hear city sounds. There are so many things going on around you, it’s as if you were in a closed system, a small town in itself. So you make an abstraction of everything that’s outside because you don’t have access to it.

R&K: This reminds me of an inmate in your video, who says that having a phone in prison means hanging on to the outside world.

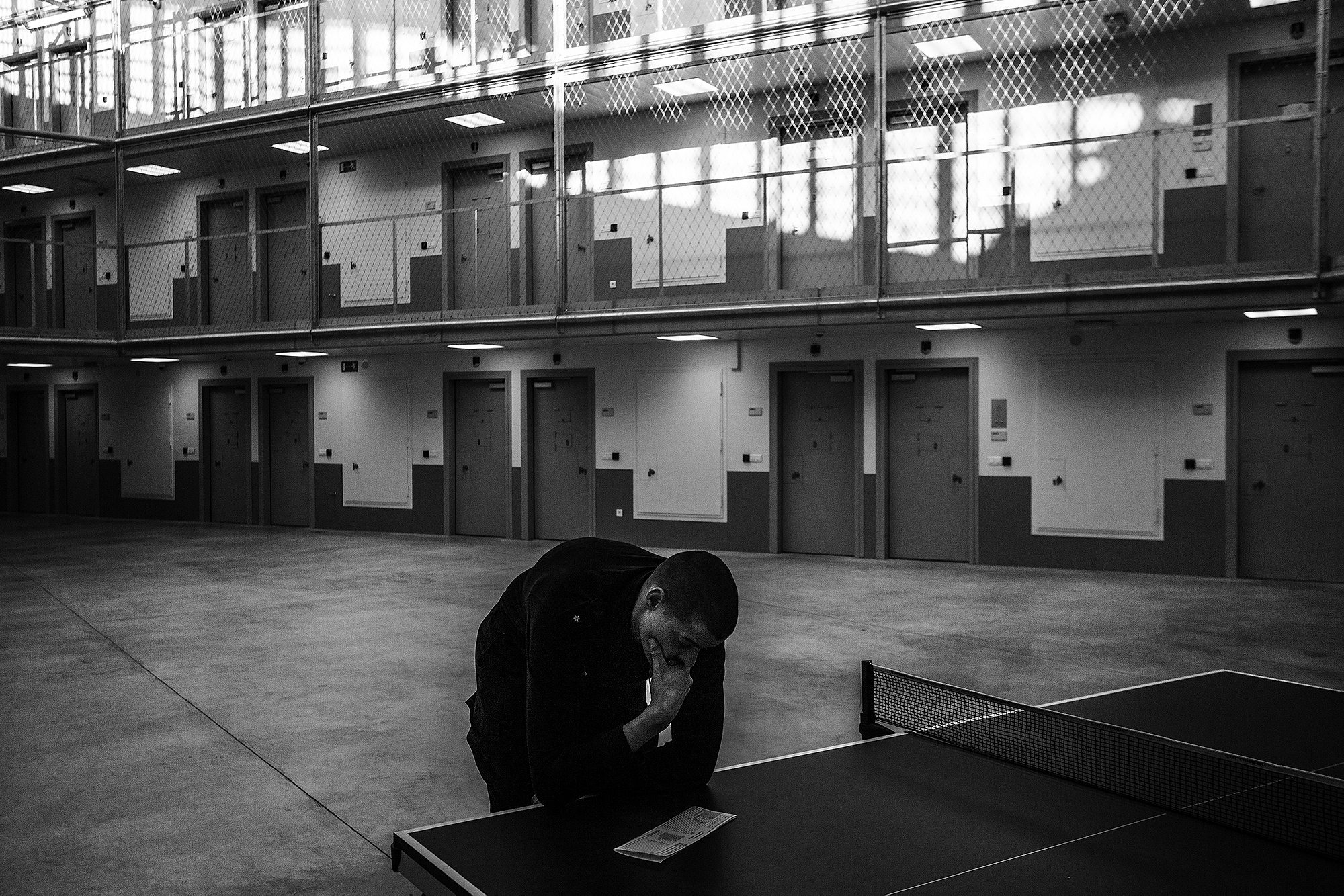

Van Malleghem: Yes, exactly. Those who have a phone in prison are forcing their own existence because in the eyes of the outside world, they don’t exist. Everything is so opaque inside. You don’t know how the rest of the world is doing. The only thing you can see is the weather, but you can only look straight above you. You don’t see the horizon. Not only was your freedom taken away, but so was your socialization. And that’s crazy. On the other hand, a lot of things are smuggled into prisons, almost everything really. But if it was a guard that got you a phone, and I say “if” because there are other ways, he can also decide to search your cell the next day. So there’s a lot of hypocrisy, and I think what this inmate is really saying is that having a phone in prison is useless.

R&K: How did you react when people said to you: “when you’re in prison, you don’t exist”?

Van Malleghem: I just thought, wow, how could this be possible in 2015? It puts into question all these reintegration programs. For example, I don’t understand why inmates can’t have decently-paid jobs. Today, in Belgium, they are paid in cents per hour, euro cents. I’m not asking for minimum wage here, but working for cents is slavery.

R&K: Is there something that’s specifically Belgian about this project? Or do you see it as universal?

Van Malleghem: I think it’s universal in the sense that it asks questions about what incarceration is, what confinement is, what prison is. But because I was asking these questions in Belgium, I was let into these places and I was able to work, just like with my “Police” project. I believe there are less and less countries where you can do that. In France, for example, you wouldn’t be able to photograph inmates’ faces. In many parts of the world, everything that is government-controlled is extremely protected and extremely difficult to photograph. In Belgium, even if it’s hard, it’s possible. So in that way, I think there’s still an open-mindedness here and I’m very grateful for it.

R&K: Some prison directors went as far as inviting you so that you could document the conditions.

Van Malleghem: Yes. Certain prisons are in bad need of funding and the government doesn’t do anything to help. The Forest prison in Brussels, for example, is like a factory. People don’t even have names anymore, they have become numbers. They come through and they’re dispatched throughout the country. The living conditions are deplorable. The walls are crumbling. This is where I took the photo of the toilet, which is used by the inmates who work in the workshop. So yes, certain people in charge said to me: “we are going to show you everything.”

R&K: Why aren’t these conditions improving?

Van Malleghem: Because I think that Europe is still going through a crisis. There are prisons that do try though, where directors will put inmates to work on the buildings. But I think there’s a real lack of resources and that the government does not want to reform prisons. It’s a sensitive topic to tackle and it would require a lot of money. There are other priorities and it’s all about politics, I would say.

R&K: In your opinion, should prison reform be a priority?

Van Malleghem: Education should be a priority, especially for disadvantaged young people. I would take the problem at the root. And then obviously prisons need to provide much more psychological support and inmates should be accompanied into their new life outside. One agent told me that apart from being given a train ticket home, ex-inmates are left completely on their own. You might have some organizations dedicated to reintegration but they have no funds, they’re not supported by the government, even though I think there would be a way to create jobs. Obviously we aren’t talking about alter boys here, but some of these inmates have had very interesting lives, they know how to do a variety of things and they have potential.

R&K: Was it important for you to know the crimes the inmates had committed?

Van Malleghem: No, I never asked them what they had done. It’s the kind of thing that will stick in your mind, so I didn’t want to know because I didn’t want to look at them differently. I asked how they spent their time, how they felt when they arrived in prison, how they dealt with family, what their relationships were like with guards, what the internal organization of the prison was like… Basically, what I was trying to answer was: what does it mean to be human and imprisoned?

R&K: You also photographed prison guards.

Van Malleghem: Yes, but much less, because they were more apprehensive. Many were a bit paranoid and said they were scared of having problems outside. I can’t really explain it. They never really trust anyone. It’s as if they had been working in prisons for so long that everything they had seen and heard, all this hypocrisy, had made them suspicious of everything. It really was much harder to photograph them. However, some of them did say yes and had no problems with it. I spoke to wardens and recount their stories in the book, but I don’t want to reveal too much before it’s out.

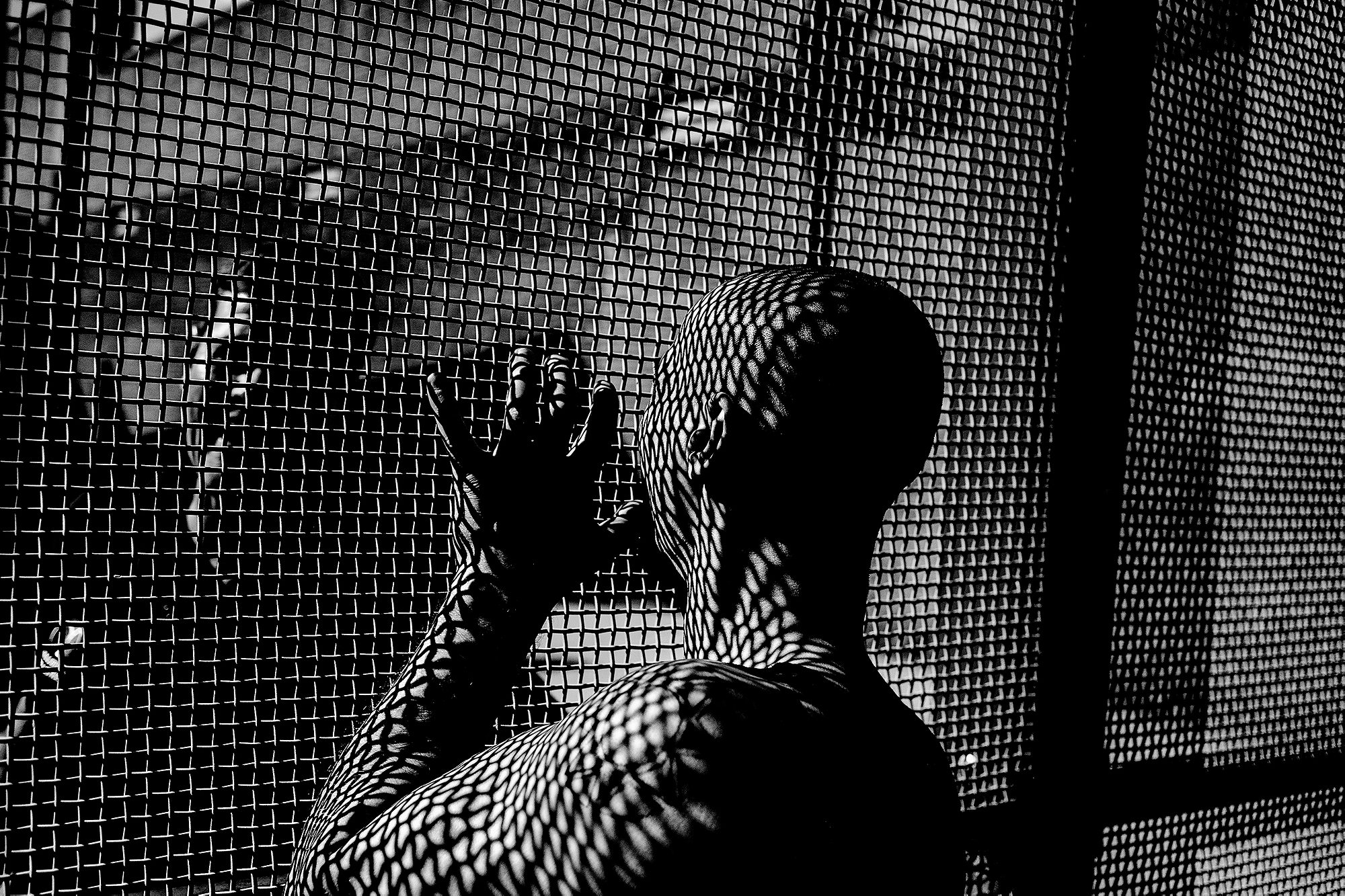

R&K: You said that this work made you angry. At what point did the project become personal?

Van Malleghem: We talk about prisons every day in the news, in TV shows and in movies. It’s a universal fetish and we are fed information that is very romanticized. Think of how the press illustrates prisons: photos of fences, of keys, no faces, no emotions. Inmates are rarely interviewed. I understand why, but I personally wanted to show the reality. I wanted to say: this is happening in our country, it’s here right in front of you, look at it, think about it. And yes, I do sometimes feel this very strong anger when I’m driving to the prisons. I’m revolted by the way we choose to treat others. My father often says to me: one day, I’ll ask you to do a project about their victims. But it’s not because I talk about prisons that I am pro-inmate. I am not pro-inmate. I am just a guy that decided to go and see, and this is the reality I was given to see. I have as much sincerity and as much respect for the victims. Of course, they sadden me and what happened to them is awful. And the inmates, they anger me and their conditions of incarceration too, and at the same time they move me. The world around me moves me.

R&K: What are you planning to work on, after “Police” and “Prisons”?

Van Malleghem: This work will be a trilogy, with the third book being about the criminal world. I started in the street, and now I’m going back to the street, on the other side of the spectrum. I’m still in the research stage right now. All my projects require a lot of time. And this one can’t be researched on the internet or one the phone, it’s all about meeting the right people.

You can help Sébastien Van Malleghem raise funds to publish “Prisons” here.