A long, expensive journey to the spring that forms the Niger River.

It’s dark by the time we arrive in Forokonia, a small village in Guinea’s mountainous border region with Sierra Leone. We’re surrounded by dense forest, and the contours of a nearby mountain are clearly visible against the bright, star-lit sky. My driver turns the engine of his motorbike off. The silence is overwhelming. Hushed voices, soft footsteps and the beams of cheap, Chinese-made flashlights are the only indications we are not alone here. I’m thrilled by the thought that the next day we might reach our destination: the source of the Niger River.

In the morning, we—Samba Diakité, my local friend and travel companion, and I—had set out from Banian, a small rural trading town straddling the main road in southeastern Guinea. It was only a hundred kilometers from Banian to Forokonia, but it had taken us more than twelve long hours to cover the distance.

This was partly due to the poor infrastructure of the region. Only a handful of urban centers in this underdeveloped part of the country are connected by paved roads. Mud tracks and rocky trails inevitably make up the bigger part of any trip to the region’s smaller towns and rural villages.

However, the many encounters with local officials, police chiefs and military commanders on the way had been the most time-consuming aspect. Each of them had jumped on the opportunity to demand a ‘present’ or a ‘voluntary contribution’ and the negotiations had been endless.

That evening, after one of the local elders of Forokonia had offered us a bed for the night, Samba and I felt exhausted and excited at the same time. There was no official purpose to our trip (which took place in early 2011) and it had been hard to explain to the locals what exactly we were doing here.

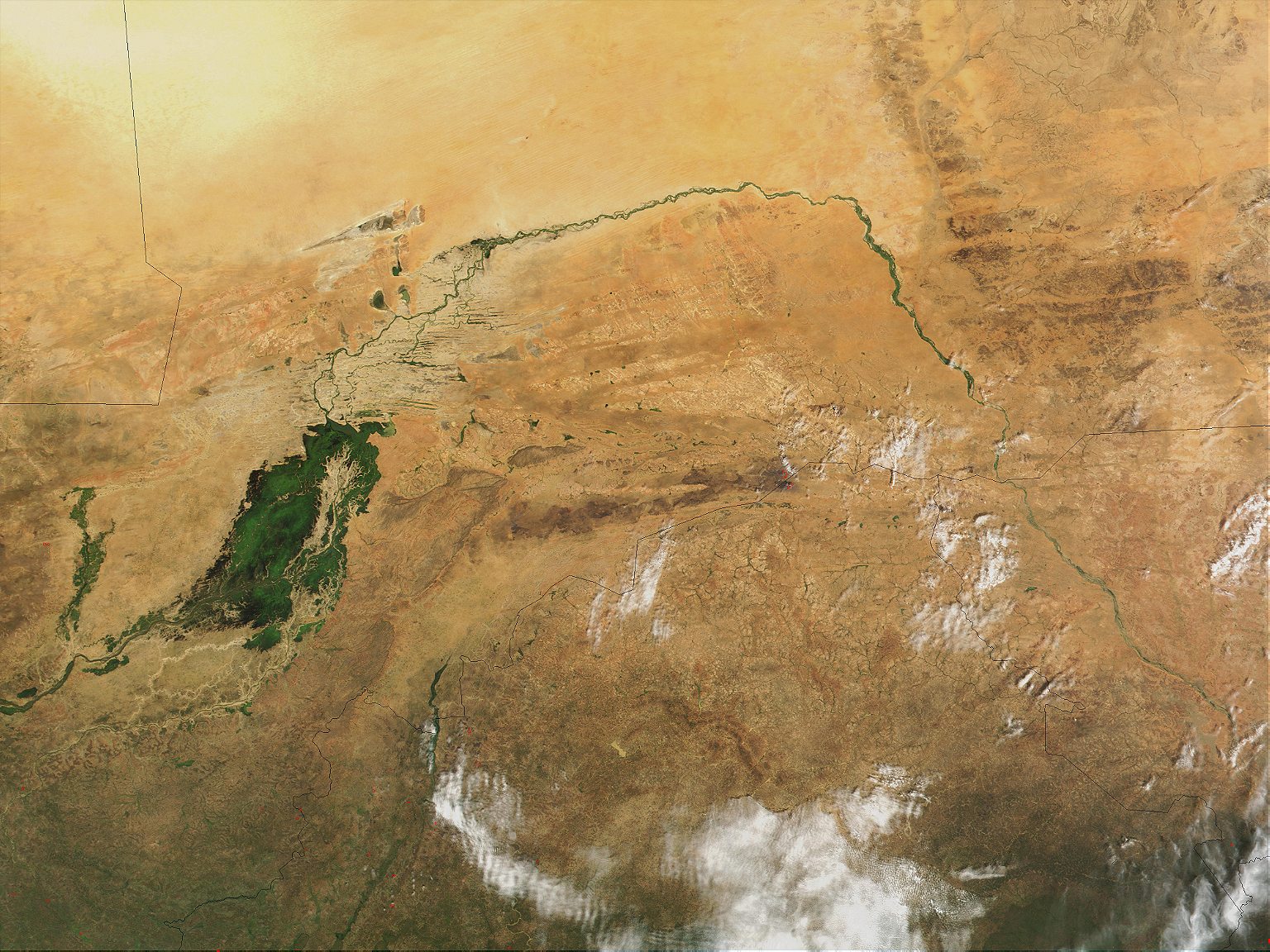

Our aim was to find the source of the Niger River, the birthplace of a lifeline that sprouts from the earth 300 kilometers (186 miles) from the Atlantic coast, and defiantly turns its back to the ocean, preferring dusty interior over the lush and breezy coastal regions. It has been a bulwark against the ever-encroaching Sahara desert for thousands of years. The Niger has made life possible in places that otherwise would have been uninhabitable.

Banian, the starting point of our trip, was buzzing with activity. Hundreds of people had flocked to the town for the weekly market. The majority of the market vendors were local villagers and small-scale farmers, selling the surplus of their harvests to buy essential goods: tools, cloth, batteries, cosmetics and cigarettes.

Most of the market stalls were simply a cloth or a few newspapers spread out on the ground with small heaps of fruits and vegetables stacked on top of them. Buying anything was surprisingly difficult. The vendors were predominantly women, and they were so caught up in the conversations with their neighbors – discussing the latest news and exchanging the latest gossip – that it was hard to get their attention. The weekly market was as much a social affair as it was an economic one, and the former clearly took priority over the latter.

Samba kept on ridiculing my attempts at buying some supplies for our trip. “You have no idea how out of place you look,” he laughed, before finally giving in to my desperate pleas to help me out. With his support, the job was done in no time. For the total sum of just one dollar we bought four bananas, three oranges, a packet of cigarettes, one liter of water, bread and two fresh hibiscus juices. Finally, our trip could begin.

Finding transport for the first leg of our journey was easy. The driver of a shared taxi agreed to take us to Banbaya, a village at the foot of the Loma mountain range that forms the border between Guinea and Sierra Leone.

Together with eleven other passengers we squeeze ourselves in a 20-year-old Toyota station wagon. The driver skillfully packs every available space in the car with goods and people. Samba and I occupy one of the front seats, and another passenger shares the driver’s seat; four people sit in the back, with three kids standing between their legs, and two women occupy the trunk, which is left open, while one of them nurses a baby. Several large bales of merchandise are strapped to the roof and serve as seats for an additional four men.

At this point, I’ve traveled quite a bit in Africa, and have become well versed in the packing and stacking procedures that come along with traveling in local buses and shared taxis called ‘sept-place’ (seven seats—an understatement). But this driver is breaking all the records. Eighteen people plus luggage in a station wagon.

It takes us two hours to cover the 30 kilometers to Banbaya, which feels like a ghost town now that all its inhabitants are either working in their vegetable gardens, or visiting the market in Banian. But the town is not entirely deserted. As soon as we arrive, we’re approached by an old man who asks some money to buy his daily portion of kola nuts, the popular caffeine-rich fruit used as a light stimulant. Initially, I refuse the man’s request, but then, thinking karma and realizing that we will be depending on the goodwill of others to reach our destination, I change my mind and hand the man some money.

The man inquires about our business in Banbaya. “We’re going to the source of the Niger,” I answer. “Oh, really?” he replies, somewhat surprised, “Have you got permission from the authorities then?” Permission? Authorities? I had not expected that. I start to worry.

We seek out the local police chief to explain our situation, and he confirms that to visit the source we need special permission from the Minister of Interior Affairs in the capital Conakry, hundreds of kilometers away.

“There have been rumors of Sierra Leonean militias roaming the country’s hinterland, close to the border with Guinea,” he explains. “But, more importantly,” he says, raising his voice to stress the point, “The source of the Niger is a holy site which is guarded by the spirits of our ancestors. It is a protected place, and not just anyone is allowed to visit.”

I tell the police chief that we don’t have the time or the means to make a round trip to get the minister’s permission and ask whether there is isn’t any other way to deal with the situation. “Of course!” he replies, “But you’re going to have to pay: c’est l’Afrique.”

There was something in the police chief’s tone that struck me. He wasn’t secretively asking for a bribe, or angrily demanding money: he was simply stating the obvious. The police chief was the first of many individuals that would ask me (but not Samba) for handouts on our way to the source.

Every person with the slightest bit of authority capitalized on the opportunity to earn a little bit extra. It was clearly an abuse of power – many local villagers and farmers asked me for money, but they weren’t in a position to demand it from me, like the police chief.

Guinea is considered one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 178th out of 187 countries, according to the United Nations. Half of the country is believed to live under the poverty line, but in the rural areas this number can go up to two-thirds of the population. The highest the country’s gross domestic product per capita has ever risen is $311.65 in 2008. It has dropped again since then.

I later asked myself why everyone expected to be paid. Maybe it was a commonly expected reciprocal gesture, which since I was a stranger who was just passing through, had to be paid on the spot rather than at an undetermined point in the future. Or, maybe it was simply a way to replenish meager salaries.

So too, the police chief. After establishing our mutual understanding of the situation he tears a blank page from a notebook and writes down a few lines before handing it to me: “So, this should be enough to see you past the first checkpoint. Now, how can you help me?” I give him a few banknotes, followed by a handshake.

Our next stop is the garrison town of Kobikoro, seat of the sous-prefet and home to the local bureau of the gendarme. The road leading there is in such a poor state that it requires a four-wheel drive or a motorbike to navigate it. Samba and I had already made a deal with two young local guys we had met in Banian, the market town, who would help us get around for the next days.

The motorbike engines roar loudly every time we make a steep climb, and the breaks squeak unhealthily whenever we descend. After a scary two-hour ride, we arrive in Kobikoro. Knowing the drill, we immediately seek out the house of the local army commander, who is in charge of protecting the border.

He receives us with open arms and we exchange the necessary pleasantries—how are you, how did you sleep, how’s the family, the house, the animals, and so on—before getting down to business. Again, I explain what brings us here. The commander listens attentively, but when I present him the handwritten note from Banbaya’s police chief he looks at me in surprise. “Did you really think that this note would suffice to be allowed access to the source,” he asks.

His smile is friendly, but I can tell he’s having fun with this toubab who talks the talk, but doesn’t know how to walk the walk. He then repeats the same story: if we want to proceed, we will first have to get the minister’s written approval. Really? “Yes.” You’re sure? “Absolutely.” Is there no other way? “No.” Can’t we find another solution? “Of course we can.”

By now I must have started to hand out monthly salaries, and the rates just keep rising

Together with the commander we visit the sous-prefect and the gendarme – leaving behind some expensive ‘voluntary contributions’ before turning back to his home. Even though I have come to terms with the fact that apparently we will have to buy our way to the source – not exactly the adventure I had expected – I start to grow increasingly frustrated with the amounts of money that are being demanded of me.

Thinking of the day’s worth of provisions I could buy for just one dollar at the market in Banian, I realize that by now I must have started to hand out monthly salaries, and the rates just keep rising. However, it appears to be working, and I’ve reached a point of no return.

Filling all the necessary pockets in Kobikoro had cost quite a bit of time, and I started to feel anxious. We only had a few hours of daylight left and I wasn’t very enthusiastic about traversing the rocky jungle track to Forokonia in the dark. We finally set out, but not before the commander has appointed two of his subordinates to accompany us – for protection or to keep an eye on us, we never find out.

The next morning, after a good night’s rest in Forokonia, we set out for the village closest to the source, high in the jungle-covered mountains. The village is also home to the Guardian of the Source, a man who traditionally protects the holy site and who has final say in who is allowed to visit and who isn’t. We’d been warned by the commander in Forokonia that his permission, too, would come with a price.

To reach the village we have to leave the bikes behind and follow a small path that leads straight up the mountain. For five long hours we walk along muddy trails and slippery slopes in the semi-darkness of the dense jungle canopy. During this trek I sense a change in the general mood of our party, which, with the addition of a local guide, has grown to seven.

Everyone is quieter and seems more serious, but the biggest change I notice with Samba, my travel companion, who normally jokes and laughs non-stop but who has suddenly stopped talking entirely. Samba is a modern-day nomad, a dancer who is constant on the move, crisscrossing West Africa looking for work, teaching dance and performing with some of the region’s most famous artists. He’s originally from Guinea, and we’ve been traveling together because he wanted to show me his country.

When I ask him why he’s suddenly so quiet, his answer surprises me. “I’m nervous,” he admits reluctantly. “There are powerful spirits protecting the source. That place is one of the most important holy sites in our country.”

A few hours later we arrive in the village and meet with the Guardian of the Source. I notice that here Islam and traditional beliefs have blended seamlessly. The Guardian, a Muslim, is believed to be the only man powerful enough to summon the ancestral spirits of the ancient kings, legendary marabouts and fallen heroes that dwell at the source.

The village is built in a large clearing in the forest, high up in the mountains. Most of the houses are mud huts with thatched roofs, but the Guardian’s is made of wood, with a tin roof – a clear sign of his wealth and importance. He receives us in a dark room furnished with just two chairs, a bed and a mosquito net hanging from the ceiling. The only light comes in through a small window high up in the wall.

The conversation proceeds slowly; the Guardian only speaks the local dialect, which has to be translated into Manding, and then into French—and back again. Eventually we reach an agreement on the amount to be paid, which is many times higher than anyone else had asked before. Grudgingly I hand over a wad of money, which quickly disappears underneath the pillow on the bed.

Soon, we find ourselves outside again. Guided by the Guardian’s son, Moussa, we set course to our final destination. It’s still almost a two-hour walk, during which we occasionally cross into Sierra Leone.

In the wavering light of the brief dusk we squeeze our way between bamboo canes thick as our arms, climb over fallen trees overgrown with moss, and navigate slippery rocks covered with dead leaves and black mud. And then, we finally see it: the source. A tiny stream, like a tap that hasn’t been closed properly, sprouts from between the rocks, filling a small pool of water at an almost meditative speed.

Seeing the source instantly makes me forget about the money spent, the exhaustion and the endless negotiations. It feels like magic. Each drop is the start of a 2,600 mile journey that will see it traveling past numerous villages and ancient towns, underneath massive bridges and through the Sahara desert; each drop will be part of the uncompromising body of water that is the Niger, a highway that has for many centuries connected caliphates and kingdoms, colonies and cultures.