A journey through Brazil’s mind-blowing Inhotim art park with the eccentric mining tycoon who built it all.

When I landed at Tancredo Neves International Airport in Belo Horizonte last April, preparations for World Cup 2014 had passed the point of last-minute and were bordering on the absurd. In the middle of the concourse near a busy check-in counter, workers jackhammered at a gaping hole. The racket was deafening. Airline staff shouted instructions in vain to queued passengers covering their ears in agony.

Driving into town, more evidence of frantic upgrading—freeways, overpasses, public transit. From the driver’s seat of his tiny Ford hatchback my guide, Henrique, mused, “These are things we should have built along many years, but we decided to do everything now, just before the World Cup. It’s the Brazilian way of doing things. It’s not very good but it is.” Like many of his countrymen, he seemed resigned to the looming possibility of a fiasco but still hoped for the best.

Belo Horizonte, or BH (beagá) for short, is the capital of Minas Gerais, a state in the mining region of Southeast Brazil. I’ve heard it described as the Chicago of Brazil, because of its heartland vibe. Folks here still love their rodeos and country fairs.

In the past two decades it has sprawled, transforming itself from regional hub into bona-fide metropolis. BH is now the country’s third largest metro area, although it still feels a bit provincial. As global tourist destination, it’s way off the radar, but that’s changing, in part because of one very rich man, and what he’s building in the nearby countryside.

Over the past decade, iron magnate Bernardo Paz has converted his vast rural estate into a mind-bending outdoor art complex and botanical garden. With seemingly unlimited resources, he’s commissioned monumental works by the world’s leading contemporary artists, some in their own expo-like pavilions. In parallel, he’s gathered many of Brazil’s endangered fauna; his park now holds one of the world’s largest collections of palm tree species.

Named Inhotim, after a British engineer known to the locals as “Nhô Tim” (Mr. Tim) who once lived here, the place is Paz’s vision of paradise on earth. It began as his private property and personal art collection, but has since evolved into a non-profit cultural institution, open to the public. A kind of highbrow Disneyland, Inhotim drew nearly 400,000 visitors in 2013, according to their press office. Considering the remote location, it’s impressive.

A real-life version of Mario Kart, Brazil edition

But Inhotim is more than a mod tourist attraction, it’s a splashy philanthropic gesture by an affluent and powerful man in a region of modest means, and that makes some uncomfortable. Brazil is seen by many of its citizens as a two-tier society where the rich routinely get their way at the expense of the poor. Corruption is still rampant. This creates suspicion when a wealthy individual says he’s acting from a place of altruism, and Inhotim has not been exempt from such doubts.

So what is really going on in Bernardo Paz’s mind? Is Inhotim some kind of centerpiece to a giant real-estate ploy? Just another rich man’s folly? Or, as Paz says publicly, is it the visionary laboratory for a better future society? I had been sent by CBC Radio’s documentary program Ideas to see if I could find out.

The two-hour drive from Belo Horizonte is an adventure in and of itself. It begins with choking suburban gridlock, then transitions into a real-life version of Mario Kart, Brazil edition. The tires on Henrique’s feather-light two-seater squeal and skid around every curve as we negotiate the busy two-lane highway, no shoulder. I take in the regional landscape: thick tropical forest, grassy ranchland dotted with spindly palms and red-roofed villages. In the distance, hazy green hills bear the orange scars of mining activity.

Approaching the outskirts of Brumadinho, the closest city to Inhotim, we narrowly dodge a horse and buggy trotting nonchalantly down the middle of the road. We pass a dozen or more tiny roadside snack bars where locals sip beer and lounge in the afternoon shade. I suggest we stop for a cold one but Henrique counsels otherwise. “We call places like that a ‘dirty glass,’” he jokes, laughing at my attempt to keep it real.

Upon first encounter, Brumadinho seems pretty rough around the edges, although it’s hard to know if it is just typical mining-town shabbiness. The city is frequently described as poor by visiting reporters, but because of well-paying resource sector jobs, it actually boasts one of the highest per capita incomes in the region. Noisy and chaotic, it’s light years away from a typical tourist town—cars and trucks roar by, blaring bass-heavy jams from souped-up speaker boxes. The main artery is clogged with cement trucks and flatbeds and tour busses headed for Inhotim.

After a long game of stop-and-start, an institutional brown sign offers relief: Inhotim is the next right. We turn. Three kilometers down a bumpy setted road, wild growth begins to be been tamed by careful landscaping. Traffic noise fades and birdsong is audible. We’ve reached the oasis.

Entering Inhotim is different from most mass tourist attractions I’ve visited. There is no being herded through a maze of winding gates. From the parking lot, you’re made to walk a good distance down a wide stone path, beneath a canopy of palms. The air is immediately cooler—you chill out and leave the stressful drive behind. Electric golf carts breeze by, piloted by fresh-faced staff in color-coded t-shirts. Tourists with backpacks, young to old, stroll down the shady lane. Various accents and languages abound but Brazilian Portuguese dominates.

At the main entrance, it’s the gardens, not the art, that first make an impression. They verge on hallucinatory. Palms, from bright to pale green explode like fireworks on backdrops of leafy eucalyptus. Neatly groomed lawns hug curving ponds replete with gliding swans. A golf-green peninsula juts out into a placid lake like the 17th hole at Sawgrass. Big clumps of foliage hint at deep dark jungle. It’s impressive to see nature bent to the will of man, yet still retain its primeval energy.

The gardens are influenced by the design ideals of Brazil’s master landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, who was a personal friend of Bernardo Paz. “He never did anything in Inhotim, but I think he’s inspired all of us and all landscapers that work here,” says Letícia Aguiar, manager of Inhotim’s gardens. “You never see straight gardens in Brule Marx gardens. You see curves—the garden never reveals all at the same time. You are walking and the garden reveals itself [gradually].”

Letícia explains that the landscapes are intended as sensory balm between artworks, some of which can be extreme or disturbing (a piece by Adriana Varejão, Paz’s ex-wife, is a crumbling wall with an interior of mock raw flesh). The gardens serve as a kind of mental palate cleanser before moving on to the next intense art experience.

I spend the afternoon exploring the park and the signature artworks that occupy its some 110 hectares. I can see why an artist would jump at the chance to show here—each piece is given the space and resources to exist in its own mini universe.

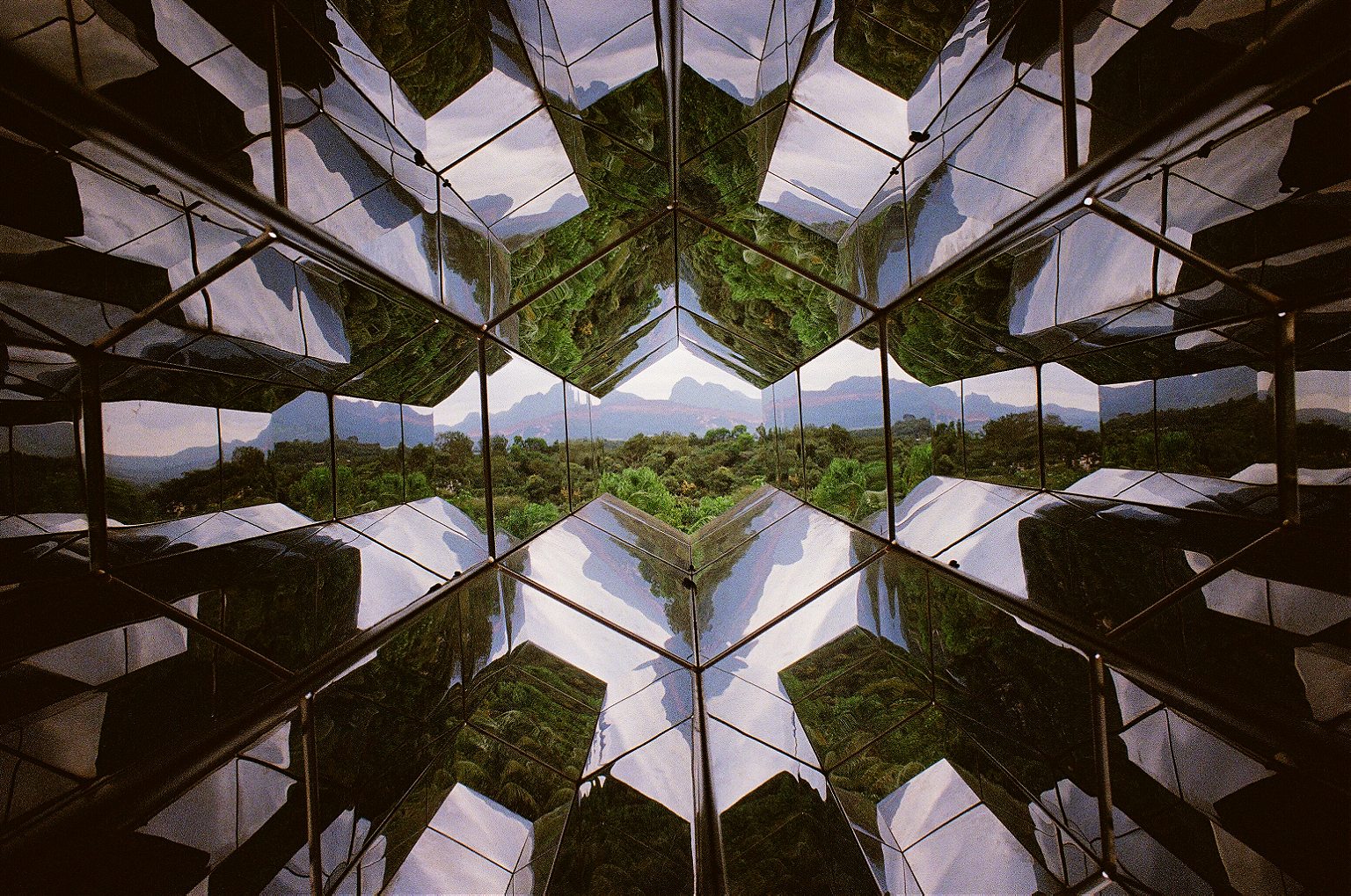

Site-specific works like Olafur Eliasson’s Viewing Machine, a sort of jumbo mirrored kaleidoscope, are set into custom-designed landscaping. Indoor works like Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s audio narrative The Murder of Crows live alone in purpose-built pavilions. The architecture of these galleries is impressive—art in its own right—running the gamut from faux villas to stark modernist cubes and funky geodesic domes.

The collection is a who’s who of global conceptual superstars (Eliasson, Matthew Barney, Dan Graham, Giuseppe Penone) mixed with influential Brazilians (Tunga, Lygia Pape, Hélio Oiticica). Several works explore the interplay between the man-made and the natural, like Penone’s Elevazione, in which a cast bronze chestnut tree has been raised and surrounded by five real trees which will, in time, gradually absorb it. Others seem to wryly acknowledge the vanity of the place itself: witness Narcissus Garden by Yayoi Kusama, a sea of floating mirror-balls that endlessly reflect the viewer’s image. (It’s worth noting that many of these pieces were not specifically created for Inhotim, but selected after the fact by the institution’s curators.)

Who knows what the general public takes away from these strange totems. Paz has said that he values contemporary art because it is experiential rather than cerebral and I do overhear a number of clever interpretations from visitors. On balance, Brazilians seem more open-minded to far-out art appreciation than we North Americans; even so, it’s hard to judge how many are there just to gawk at the strangeness of it all.

To add to the novelty, Inhotim offers many from the surrounding region a rare chance to glimpse foreigners in person. A little girl in a bright orange shirt, in attendance as part of Inhotim’s educational outreach program, comes up to Henrique and asks about me, “Why is he so white?”

It’s pouring rain, the Wi-Fi’s out and I can’t sleep. On the other side of the paper-thin walls of my tiny room, dogs bark relentlessly as a house party shifts into high gear. After two days of commuting from Belo Horizonte – and against the advice of my guide – I’ve decided to spend the night at a modest Pousada (Bed and Breakfast) in Brumadinho. My hostess, who speaks no English, has retired to her house for the night and I’m here alone, staring at the ceiling.

Tomorrow morning I finally get to meet Bernardo Paz, and maybe to catch sight of what is truly behind the Inhotim ambitions. I want to be well rested. Giving up any attempt at sleep, I switch on the TV. A suave preacher in a cowboy hat croons in Portuguese about Jesus to the strains of an accordion-laced country tune.

Finally, around one AM, the hubbub dies down and I start to drift off… only to be jolted awake by laughing voices and the low rumble of a car stereo with the bass cranked to eleven. A party that broke out in the street feels as if it has moved into my room.

Desperate for shut-eye, I call my hostess, waking her. She shows up with her brother, looking sleepy-eyed and unimpressed. They graciously drive me to the tourist hotel Henrique had recommended for me in the first place, and watch as the gringo walks through the gates to cushier digs.

Settled into my new quarters, I crawl into bed to salvage what rest I can. But two hours later, I’m roused again, this time by a man droning loudly through a megaphone. Voices chant rhythmically after him in response. I go to the window: a long white procession is shuffling by my room. It’s Holy Week and the citizens of Brumadinho are expressing their faith in the streets–at five in the morning.

When I arrive at Inhotim, throngs of weekend visitors are waiting to get in. I’m fighting fatigue, but pumped to finally interview the man behind it all. Isabela, a press agent, greets me and we’re off. We find him sitting with guests around an outdoor table at one of Inhotim’s swanky restaurants. Paz rises.

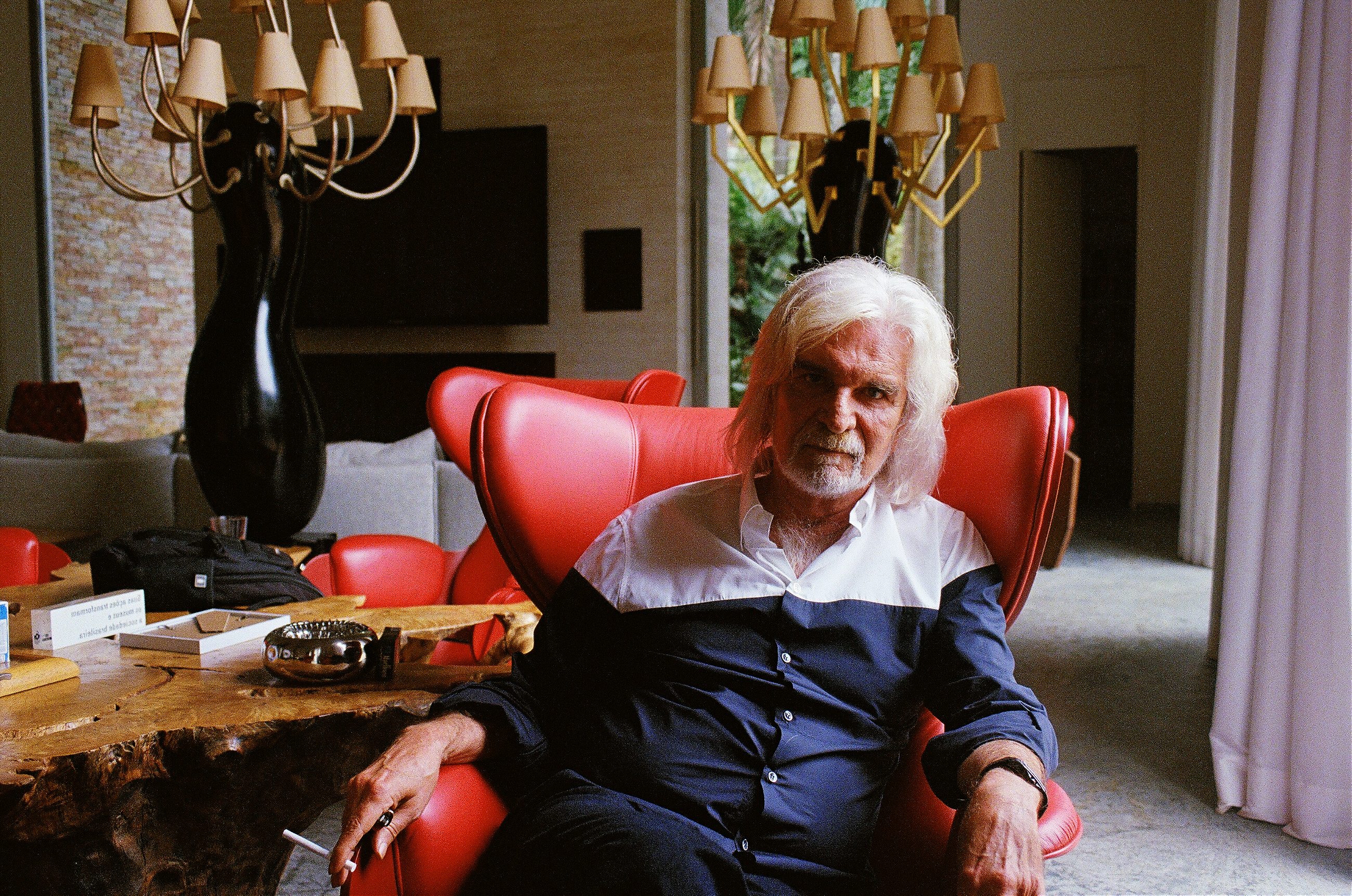

At first, I’m a bit star-struck. He’s tall and tanned, with a wild cloud of white hair framing his bearded face–sort of like a Latin version of Richard Branson. A self-made tycoon, married six times, who’s poured his fortune into making a fantasy real, he just may be The Most Interesting Man in the World.

As we walk he rambles in a stream of consciousness, mostly about his plans for Inhotim. Blue eyes flash a nervous energy. He’s been called “The Emperor of Inhotim”, but employees treat him not so much with deference as with reverence, lacing the conversations they have with me with quotes directly from Paz himself. What he’s conjured here has obviously created true believers.

As we drive via golf cart to his nearby house, our progress is slowed by masses of sightseers entering the park. He has built it, and now they’ve come. A family is trying to snap a photo of a capybara by the water, and he stops for a minute to avoid spoiling their shot.

Paz lives in the park itself, just off the beaten path. Clean and modern, his residence is luxurious, but not extravagant. We sit down for an extended interview, during which he chain-smokes Marlboros, skipping from one topic to another, covering everything from Occupy Wall Street to European immigration. He talks about his mother the artist and his father the military man: “You had one side, a woman who lived the dream, and the other side, a man who wants to be a hero,” and about a formative experience in Mexico where he says he became acutely aware of the great barrier between rich and poor.

Talk invariably turns to the future. With Inhotim’s reputation as a world-class art institution and botanical garden secured, he’s set his sights on loftier goals. Paz sees dark days ahead for the world’s megacities, which he thinks have become unlivable: financial collapse, political disillusionment and violence. Inhotim will be an example of a new village-based way of living, a “post-contemporary society,” which he sums up as, “To come back to your grandmother’s house with technology. This strikes me as clever but contradictory: isn’t being plugged-in the very thing that makes us yearn for simpler times?

He says next step at Inhotim is for visitors to become converts by staying for extended periods. First temporarily (a hotel is under construction), and later permanently. He dreams of a day when interconnected communities will dot the surrounding hills. “I want to build some villages as a sample. And build this world again. But this world will come in this way: to go back to the past with medicine, with science and with technology.”

I ask him why he thinks this will work when other utopian ideas have failed. “This is not a utopian idea,” he snaps.

As we leave, I notice, near the pool, a golden sculpture of a male figure suspended horizontally, poised to plow headfirst into a heavy bell. Based on its prominence, I sense the piece resonates with its owner. Paz has faced his share of resistance and he certainly has his skeptics.

One of Paz’s toughest critics is Marcos Hill, an art historian and professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) in Belo Horizonte. “Inhotim is a terrific place for entertainment where you can have some contact with art issues in a very superficial way… I think Inhotim is a marketing, capitalist idea. I don’t see anything utopian over there. Bernardo Paz is a very smart businessman and he wants power, he wants money, he wants privileges. And nowadays he can hide behind Inhotim.”

Allegations of money laundering have swirled around Inhotim, although nothing has been proven. It’s a topic many bring up without me asking, including Paz himself: “Money laundering. Why did this guy who has a lot [build Inhotim]? [The investigators] come through. And in they end they know it was nothing. But they made me lose six months… Why? Because there was nothing and they create that. How? They don’t believe.”

A smoke screen for a capitalist’s shady dealings?

Paz says he’s poured between four and six million dollars a month into the project for fourteen years, a figure which doesn’t seem unfathomable considering the massive annual expenditures it clearly demands. If Inhotim is just a smoke screen for a capitalist’s shady dealings, it would surely be the most elaborate and expensive one in human history.

Others don’t necessarily see self-interest and public good as incompatible. Diomira Faria teaches the economics of tourism, also at UFMG, and has studied the impact of Inhotim on the surrounding region, “[Paz] is a mining man and here, near Belo Horizonte, you can visit some high income condominiums that were part of mining areas,” she says. “So suppose that Bernardo Paz intends to do the same in the Brumadinho area. [I think] Inhotim, it’s a seed of a big real estate business.” For Faria, this capitalist vision could offer benefits. “In [Paz’s] mind he thinks that the beauty can change people and he thinks also that Inhotim is a kind of present to the people… Inhotim is a business, but also a good thing [for] this area that can change people.”

It’s difficult to divine motives, especially those of a wealthy eccentric. It’s much easier to judge results, and the results of Paz’s efforts on some level dazzle even his harshest critics. Marcos Hill acknowledged that despite his cynicism, he still brings his students to Inhotim every year, because they can see art here they can’t see anywhere else.

As the sun starts its lazy descent into the hills, the park starts to empty out. It’s last call for Inhotim’s most far-flung work, widely considered its signature piece, Sonic Pavilion by Doug Aitken.

On a rocky mound overlooking a vast forested expanse, sits a round building made of curved glass. I climb the steps and enter. Inside, it’s bare, except for a small hole bored into the center of the floor. Gradually, an intense bassy vibration envelops the room. Six hundred feet down the shaft, ultra-sensitive microphones are broadcasting the sounds of the earth. Art for a mining king. The sensation is physical, elemental. I sit for a while and listen to the ground move as I take in the panoramic vista of red earth, green trees and blue sky.

I exit the building. The smell of rain is in the air. The woods are looking blacker and denser, the sound of the bugs and birds seems amplified as fewer and fewer visitors can be heard in the distance. Waiting for the golf cart that will bring me back to the exit gates, I hear a female voice, sweetly singing in Portuguese. It’s a young gallery monitor, innocently skipping and humming outside the pavilion door.

Maybe Paz and his devotees are right: a garden filled with beauty and truth can help us regain paradise, if we just have faith. But, as Brazilians know well, the devil is always in the details.

Special thanks to CBC Radio One’s documentary program Ideas, who produced the original radio version of this story, which can be streamed here. Thanks also to the show’s Producer Dave Redel and Executive Producer Greg Kelly.