Log cabins! Water slides! Rotisserie chicken! In Dolly Parton’s Tennessee hometown, Americana gone awry

Driving along the main thoroughfare of the Great Smoky Mountains Parkway in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, you pass signs for Wild West-themed shopping centers, an arcade, an Egyptian Tomb attraction, the Biblical Times Dinner Theater, candy shops, outlet malls, seafood buffets, Fantasy Golf, old-timey photo shops, and endless signs for roadside motels with names like the Valley Forge, the Mountain Breeze, and the Americana.

Finally, you reach the parking lot of the Dixie Stampede Dinner Attraction, next to a Best Western, a Texas Roadhouse Steakhouse, and a Days Inn. You could be anywhere in the United States, but you are not. Up ahead is a sign for Dollywood and Dollywood’s Splash Country, and the hedges that line the parking lot have been cut into the shape of stars and decorated with blue lights.

You are in the childhood home of Dolly Parton.

Although the town was named for its nineteenth-century iron forge, today it is primarily a tourist destination, a place designed to entertain and divert. When I visited not long ago, the town was already in full Christmas swing, its parking lots crammed with tour buses and SUVs, out of which poured visitors in Santa hats and Christmas sweaters.

The rodeo-inspired Dixie Stampede Dinner Attraction is just one part of the ever-expanding Dolly Parton brand that also includes Dollywood, Dollywood’s Splash Country, and Dollywood Cabins, as well as Dollywood DreamMore Resort, which will open next summer. The website for the Dixie Stampede declares it “The Most Fun Place to Eat!” as well as “A fun-filled, action-packed extravaganza that everyone should experience.”

‘Fun’ is a big part of the Dolly brand, and the website is no stranger to hyperbole or exclamation marks. Dollywood is “The Friendliest Place on Earth,” a space in which conflict is inconceivable, even forbidden. Of course, all amusement parks create a space apart from reality, but part of Dolly’s appeal lies in her ability to convince her fans that this world is real. This sense of real is largely grounded in her childhood poverty, which informs her public persona as much as her adult musical career, and many of her most famous songs like “Coat of Many Colors” retrospectively imbue this childhood with a wistful sense of nobility. Poverty as character building.

It’s easy, and in many ways important, to critique this position, but there is no doubt that Dolly effectively negotiates complex issues of class in the U.S. She is an adored queen who presents herself as a down-home gal, and in a world of inauthentic celebrity performances, it’s hard not to believe her. Her love of “roots” and her refrain that she never forgets where she came from is the best advertisement Pigeon Forge could possibly desire. The town becomes no less than the embodiment of rural American authenticity and potentiality, with a benevolent guiding spirit watching over it.

When I visited, the Dixie Stampede Dinner Attraction appeared to be tremendously attractive indeed. Its three daily shows almost always sell out, as do its five daily shows around Thanksgiving and Christmas. When I booked my ticket for Thanksgiving week, I was told to come an hour and a half early for the pre-dinner show in the Dixie Belle Saloon. The parking lot was ablaze with Christmas lights, every inch of every tree glowing. And above the parking lot hovered the lighted Dixie Stampede sign, which was flanked by glittering American flags.

A middle-aged man and a woman with three children rushed past me.

“Let’s get a picture before we go in,” said the mother, trying to gather up the kids.

“Oh, come on,” said the father. “There’s nothing to take a picture of in the parking lot.”

“I love this car,” she said. “We should take a picture in front of this.”

She stood next to a van that was entirely covered in advertisements for the Dixie Stampede. Out of the top of this vehicle emerged a large plastic man dressed in a blue shirt with stars and red-and-white striped pants. He rode a bucking white horse and trailed an American flag behind him.

The old-fashioned clapboard houses and storefronts suggested the main street of a Wild West town. One building resembled a red barn, trimmed with white and surrounded by a picket fence. On the fence was a sign that read Cast Members Only. But that was a restricted entrance. The rest of us would pass through several stages before dinner, like questing heroes entering a magical realm. For me, the first stage was the gift shop.

The shop’s wide plank floor suggested wood but felt like plastic and was distressed to look old. The gift shop had two main purposes: to sell the Dolly Parton brand in as many material forms as possible, and to actively construct a nostalgic American and regional past that would also define the show. There were Dolly key chains (approximately 30 different designs), personalized Swiss army knives, shot glasses (at least 10 designs), souvenir coins, mugs, pens, rulers, Dixie Chicken Rub, and Dixie Original Creamy Soup Mix (“A classic recipe… from the kitchens of Dixie Stampede!”). A rack of DVDs—all Westerns—offered fictionalized narratives of a lost American past. Shelves were stocked with stacks of cowboy hats in every imaginable color, including sparkling gold and silver. A gun rack displayed brown and pink plastic rifles. The sign above the cash register read Shopkeeper.

Like Dollywood itself, the Dixie Stampede is not overly fond of the modern world. Its ideal customer is the American family—a unit, not an individual—and it is concerned about how this unit is faring. The Dollywood website promises “family togetherness” and “family enrichment” and proclaims that, “Dollywood is more than just a world-class theme park. It’s a compete getaway for families looking to reconnect with each other in the beautiful Smoky Mountains.”

Reconnect with each other. Families are alienated from one another; our supposedly technologically connected world is a place of estrangement and division. The world beyond the theme park is demanding and exhausting, as the website for Dollywood’s Splash Country suggests in urging the visitor to “unwind,” and it is hostile to romantic notions of all-American family togetherness.

Another couple walked past me, their two children rushing about and picking up stuffed bears, wooden yo-yos, tops, and playing cards.

“I want to get one of those things,” said the father. “What are they called?”

“A cast iron pan,” his wife replied.

“Yes, I want to get one of those.”

If you are allergic to animals or peanuts…

The gift shop was a threshold over which the capitalist subject passed into a world of cultural nostalgia. It presented a vision of the Smoky Mountains as authentically American, a part that stands in for a whole. A large photo of Dolly holding a stick horse watched over the entrance to the shop, promising a comforting space associated with childhood, a place apart. A collection of stick horses in glass cabinets also lined the hallway—or “carriage house”—through which we all shuffled forward to have our tickets checked.

Over this hallway, a sign announced:

Our show includes a number of animals. Peanuts are served in the Dixie Belle Saloon. If you or anyone in your party is allergic to animals or peanuts, or have asthma affected by exposure to animals, please take all necessary precautions, including deciding to visit our show.

Luckily, I’m allergic to neither animals nor peanuts, so I proceeded without fear. I passed holiday displays of fake gifts and poinsettias, a wall of brochures of things to do in Pigeon Forge, and advertisements for the Pirate Voyage in Myrtle Beach and the Smoky Mountain Knife Works. A smiling gray-haired woman took my ticket.

“Are you with this gentleman?” she asked. I looked at the man behind me, who was dressed entirely in camouflage.

“No.”

“Oh, excuse me,” she said. “Are you with this gentleman?” She gestured at the camouflaged man’s friend.

“No, it’s just me.”

“Oh, okay!” she said.

We moved slowly forward, down a winding hallway, the deferral of our final destination increasing our desire for it. Before entering the saloon, families were encouraged to have their pictures taken in front of green screens. I slipped past before anyone could force me to be photographed.

The saloon was a large room filled with long tables, a cross between a conference center and a honky-tonk. The second-floor gallery looked down on the main floor and the stage, which for the time being was empty. The room was rapidly filling with people, all of whom clutched plastic mugs in the shape of white cowboy boots with Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede emblazoned across them. On the walls were posters of Buffalo Bill and reproductions of old black-and-white photographs of ghost towns.

I walked up to the concession stand, which advertised pre-dinner snack options of popcorn, nachos, and roasted peanuts, as well as bright orange frozen drinks called Orange Blossom Specials (“A Delightfully Frozen Orange Sherbet”).

“Do you have beer?” I asked.

“Just root beer,” the woman behind the counter responded. She wore a red frilly Wild West prostitute-style dress with a crinoline, and her hair was pulled back with a black velvet ribbon. An instrumental version of “White Christmas” rang out from the loudspeakers, competing with the voices of families and groups of schoolchildren making their way to their seats.

This stage of the evening was designed to rally the belief that the Dixie Stampede’s Christmas festivities were both Southern and universal. The message was clear: Everyone celebrates Christmas. Everyone. But we do it best. Like the souvenir store, the musicians performed nostalgia and an intense desire for “an old-fashioned mountain Christmas,” but they didn’t shy away from appropriating popular culture. Their rendition of the theme song from National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation brought down the house, rousing sullen teenagers from their iPhones and propelling them out of their seats. I drank my water out of my cowboy boot mug and watched the teenagers sing along. They also sang along to “Jingle Bells,” “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

The crowd wanted the same thing that Clark Griswold wanted: a good old-fashioned family Christmas, a thing as fantastical and elusive as Santa Claus himself. This was what they had come for, and this was what they would get. It was a frenetic atmosphere. Songs were rarely played in their entirety—just enough to jog the memory, encourage everyone to sing along, and then move on. The band members repeatedly insisted that they were really just a bunch of hillbillies, a claim backed up with a hokey rendition of Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing,” in which the line “I want my MTV” became “I want my two front teeth.” Puns abounded. A brief and ill-advised attempt to rap “Up on the Rooftop” was concluded with the joke, “Well, that just about raps that up.” The group of kids behind me screamed with approval.

In time, the band did wrap things up and instructed us to make our way to the arena for the main show. I already felt utterly lost in the building. There were no windows anywhere. I suspected I might have somehow ended up underground, and this second stage of the journey did not help me to orient myself. I walked upstairs. I walked downstairs. I walked along hallways, nestled up against my fellow humans as in a New York City subway car. Everyone tried not to spill their bright orange drinks.

I ducked into the ladies’ room, where the stalls were adorned with handles made of horseshoes and divided between “Northerners Only” and “Southerners Only.” The communal spirit of the saloon seemed to have disappeared. I had two options, and I didn’t know which one to use. The Dixie Stampede was making me question my identity. I chose the Northerners stall and vowed to use the Southerners stall later.

These stalls were a sign of what was to come: a show that was partly about horsemanship, partly about Jesus, and partly about the South versus the North. As a waiter dressed in a green outfit and a green Santa hat showed me to my seat, other employees came around selling green Dixie Stampede flags. I was situated at the very end of Row E on the “North Pole” side of the arena, across from which was the “South Pole.” The arena was divided into rows with long, narrow tables decorated with fake oil lamps wrapped with red and green Christmas ribbons.

My row filled up quickly, as did the entire arena, which seats 1,900 people. The waiter sat a large family and a middle-aged couple next to me and welcomed us all to the Dixie Stampede. An enormous projected recording of Dolly Parton also welcomed us, and then the host “J.T.,” dressed in an Elvis-esque red sequin jacket and riding a white horse, welcomed us all over again, assuring us that we were his guests and would be well taken care of.

Our waiter seemed to be in charge of a large section of several dozen people. He told us that we were in for a real treat and that our “four-course dinner” of cream of vegetable soup, a rotisserie chicken, pork loin, a baked potato, corn on the cob, biscuits, and an apple turnover would be served without silverware. We were to eat with our hands.

The man next to me looked stunned. “Is he kidding?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t think so.”

“Would you like a soda?” our waiter asked me.

“No, thanks,” I said. “I’m good.” It appeared that the dinner was teetotaling, too—all part of the good, old-fashioned family fun. I made a mental note to bring a flask if I should ever end up back in this place.

Our waiter smiled warmly and dashed off to fill drink orders. Below, the Dixie Stampede brand was projected in lights on the arena’s sand. I thought about the sand in the Colosseum in Rome, which absorbed blood particularly effectively. At the far end of the room was a stately white house that was part Victorian mansion, part White House, and part plantation, trimmed with Christmas lights, holly, and red ribbon.

This rodeo-holiday spectacle comprised several related elements, including “trick riding,” audience competition, and Christmas interludes. The show moved erratically between these things, the host periodically reminding us how amazing it all was. His foil was a character named Skeeter who, dressed somewhat perplexingly as a deer in hunting gear, continually interrupted the show, drawing forth the host’s supposed ire and the audience’s applause. Like the band in the saloon, Skeeter insisted on his “redneck” rural Southern identity, which he performed through his buffoonery and exaggerated Southern accent.

The trick riders were flashier than Skeeter. Dressed in sequined and satin outfits like Liberace, they jumped through rings of fire and performed various maneuvers, including several with names like “Apache Hideaway” and “Cossack Drag” that could really be reconsidered. The riders’ gestures were stiff, robotic, and exaggerated, like cheerleaders, and they signaled the end of each move with a broad smile. And the activity in the aisles was as systematic and coordinated as anything in the arena below. The waiters floated up and down the aisles, holding large silver trays of food that they deposited on our plates with tongs, while the performers sang a jaunty, universalizing song: “In every language known to man, nothing speaks like suppertime!” The food kept coming. It wasn’t served in four courses so much as in a flurry of activity.

“I don’t know if I’m going to be able to finish all this,” said the man next to me.

“I think we get doggie bags,” I said.

As I tore apart my rotisserie chicken with my hands, I watched various competitions, many of which were designed for children. Kids chased chickens across a finish line. There was a pig race, in which one pig was markedly faster than the others. Members of the audience were brought down for a “horseshoe competition” with painted toilet seats. And all the while, the host kindled a supposed age-old and bitter rivalry between the North Pole and the South Pole, a debased and commodified Civil War with nothing at stake.

Christmas was the harmonizing element intended to draw us all together and to dispel this rivalry. The show’s vision of Christmas was a marriage of nostalgia and Cirque de Soleil. Performers in Victorian costumes sang Christmas carols. Others dressed as old-fashioned toys—a giant alphabet block, a bear, and a toy soldier among them—danced around with the Sugar Plum Fairy, reimagined as a butterfly, the emblem of Dolly Parton. This, too, was aimed at kids, but then the understanding of Christmas changed.

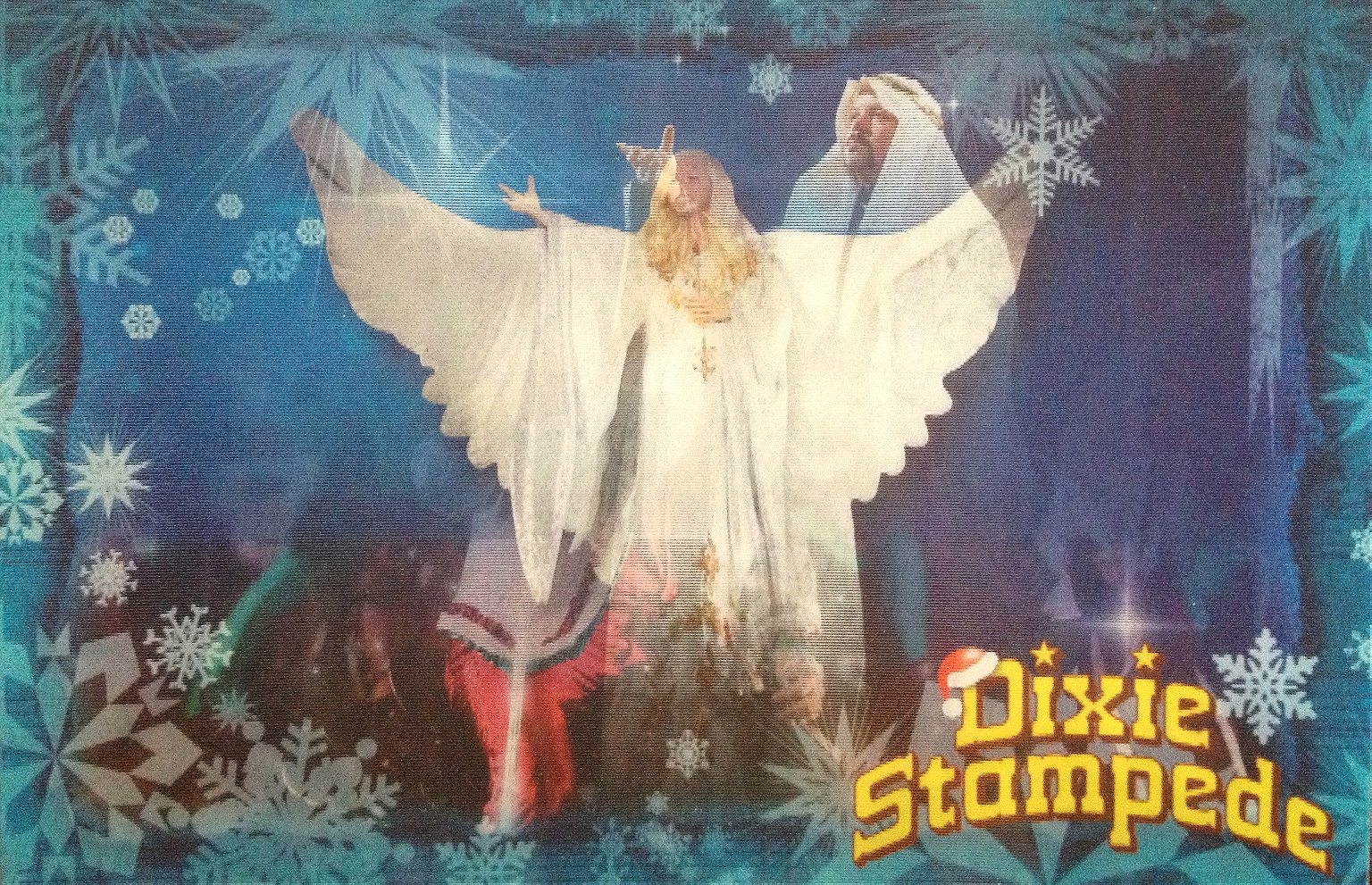

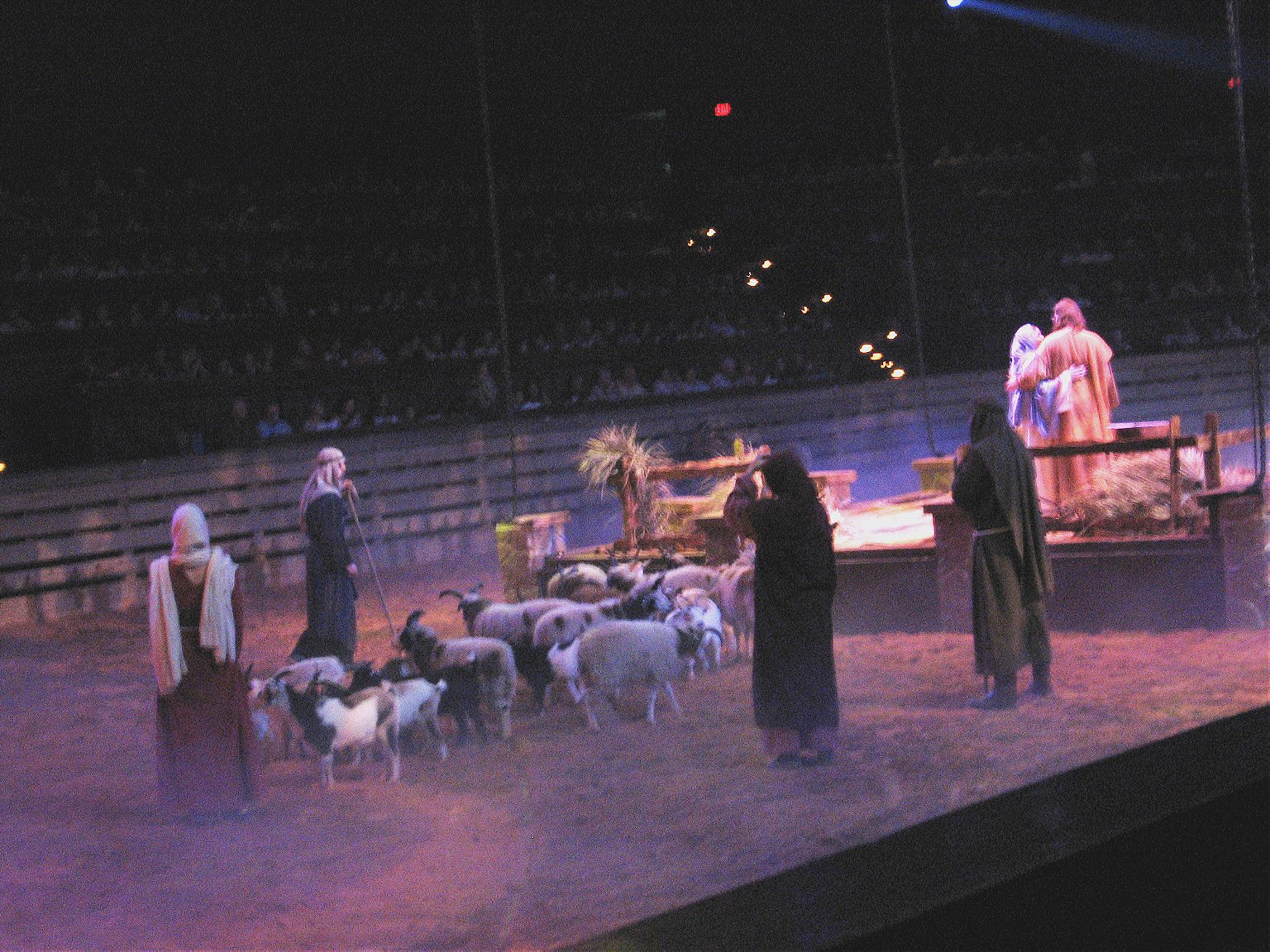

A nativity descended slowly, and Mary and Joseph sang “Silent Night,” lifting the Baby Jesus prop out of his glowing cradle and holding him up to the heavens. Shepherds drove a flock of actual sheep, goats, and two donkeys across the arena, and a God-like voice came over the loudspeaker to announce the arrival of the Lord. The Three Kings quickly followed on sad-eyed camels, which they commanded to lay down so they could dismount and offer gifts to the prop Jesus. And then, the tour de force: a blonde angel with enormous white feather wings was lowered on wires, and a white dove swooped across the arena and landed on her arm. The voice of God boomed: “This is what this great season is all about.”

Dolly, the show’s other god, made a final projected appearance to tell us that we were all “one big happy family,” and all the riders rode out, dressed in light-up sequined jackets with big snowflakes on their backs that look suspiciously like crosses, circling the arena as more fake snow fell onto the sand. Santa appeared in a horse-drawn sleigh, and the audience clapped wildly. Doggie bags printed with old-timey newspapers were distributed, and everyone bagged up their leftover food. As the performers took their bows, our waiter came by in rubber medical gloves and shook our hands and thanked each of us individually, and then the revels were ended.

On the way out, we were all funneled through the gift shop. The cycle was complete. I bought a holographic postcard, and when I tilt it back and forth, I see several moments in the show flicker across it, appearing and then disappearing. It seems appropriate that this postcard offers not one image but many, tricking the eye and keeping it from looking at anything too long or too carefully. Everything dissolves in flashes that layer themselves one upon the other, a narrative at once simple and disordered, the product of artifice.

[Header image: “Dolly Parton’s Dixie Stampede – Christmas 2006” by Jim Moore, used under CC BY 2.0]