Someone has sliced open soccer’s hourglass, and the sand has come pouring out on to the streets.

My grandfather, born in 1919, grew up playing football in a wooded corner of the British empire. The eldest son of a family of bright-eyed troublemakers from the southern Indian district of Palakkad, Kerala, he wore knee socks and a chip on his shoulder to the local missionary high school, where beatings from teachers quivering with rage were the chief method of keeping boys in line. Tempers ran high on the playground. Thanks to what must have been a combination of extreme arrogance and extreme vulnerability, my grandfather’s boyhood was marked by a determination to start or escalate fights.

Playing “soccer,” as he called it from beginning to end of his life—Edwardian slang has a certain tenacity, as North Americans will know—he was an aggressive and inconsistent forward, not notably destined for success on the field.

Although some of his brothers and friends would play the game for a great part of their lives, my grandfather gave it up relatively quickly. In the middle of the Second World War, he boarded a train for Bombay: a metropolis then, as now, suffocating in its love of cricket. On the churning streets of the vast city, he found himself stepping aside sometimes for trucks full of European soldiers, who were either passing through on their way to other theatres of war or enforcing imperial law in a restless city.

With his mind conflating the heroics recounted in one section of the papers with the other, he thought of the professional footballers in England who sometimes heaved the football from their booted feet into the net all the way from the halfway line. How easy the English made it look, he thought; and how easy it would be for a Tommy to raise his gun and fire at a brown man if he felt like it.

Through the smouldering rubble of the twentieth century, the tread of jackboots sounded often on the chalky halfway line that divides the real world from the world of the game. In a century of war, pogroms, partitions and violent revolutions of identity, football functioned as a sharp tool, loved by dictators and warmongers as much as by dissidents and democrats. (Think of AS Roma—now the “Jewish club” of Rome, frequent target of anti-Semitic chants from their rivals—which came into being in 1927 because Lazio, the great traditional Roman club, were considered insufficiently loyal to Mussolini at the time.)

Like other sports, football had been dubiously bequeathed to many countries in Europe’s colonial endeavours, and yet sometimes it helped overturn the rules it was supposed to enforce. Just before my grandfather was born, the Calcutta team Mohun Bagan won a historic footballing victory when they became the first brown team to defeat an English side in competition in 1911.

Beginning in 1930, behind the smoke and the haze, the World Cup went on with every appearance of serenity, sometimes a more just court than life, sometimes less. In 1934, played under the gaze of Mussolini, it held something of the morbid promise fulfilled by the 1936 Olympics held in Hitler’s Berlin. In 1978, under the Videla dictatorship, Argentina won lavishly at the Monumentál, even as the junta were torturing “subversives” in detention centres around the corner.

And yet, the taint of authoritarianism rarely clung to the tournament with any seriousness. When the World Cup came, it came as a festivity; a time when the joy and misery of an intense, ordered, artful universe could come to co-exist with, and often supersede, the burdens of a chaotic real world. Sport is a way of ending one routine and beginning another.

Professional football had emerged in many parts of Europe as an industrial pastime, and the referee’s whistle held something in common with the mill siren and the factory bell. For ninety enchanted minutes, it could usher in an alternate era that picked up from where the closing whistle of the previous week had left off. Its hours were marked on a different calendar; time passed quite differently there. The World Cup brought some of that regimentation to other parts of the world on a cosmic scale. Every four years, it thundered distantly against the inner ear, knocking one momentarily off-balance, and left an impression of fireworks and pageantry—or gurning and lamentation—before fading away to a murmur.

As he left his childhood behind, and a newly independent India engulfed his waking life, my grandfather, too, buried his fleeting association of white soldiers with white athletes, theirfootball played with jackboots on. By the time I was born, the sport had receded from his life, and only came roaring back through our windows for one rainy month every four years. He was 91 when he suddenly remembered the trucks full of Tommies passing him in 1943. It was July 2010, and we were up late, watching the Netherlands play Brazil in the quarter-final at Port Elizabeth. His running commentary on the game, the intermittent soundtrack of my own childhood, had begun to gently drift on to the wider currents of history. The tournament in South Africa had put him in mind of Nelson Mandela, and thence some brilliant African footballer whose name he could not recall; Brazil’s great black footballers of the Brazil of yore; Pelé; and so on, until we arrived, weaving a little, to a Bombay in wartime, and the English footballer, whose name he also could not recall, booting the ball halfway across the field.

Now the collapsing boundaries between football-time and real-time are more evident than ever.

My earliest experiences of football are bound up with him, as well as with the World Cup. If my memories of the tournament stretch back for as long as they do, it is only because my interest in football followed from my desire to look at the things he looked at, and admire what he admired. He is no longer there to watch it with me, which may be why I am thinking of the upcoming World Cup as one for which time is functioning out of joint, its carefully demarcated dream-time collapsing.

Once again, the World Cup appears to function as a smokescreen for disorder. But now the collapsing boundaries between football-time and real-time are more evident than ever. As Brazil races to complete stadiums, refurbish airports and otherwise impose order on the country in compliance with what are seen as universal rules of tournament-readiness, it seems as though June is both too far for anything to go right, and too near for anything to be ready. The protests surrounding the tournament, and the violence with which they are visibly suppressed, have had the uncomfortable effect of breaking the tournament out of its dream-time. Someone has sliced open football’s hour-glass, and the sand has come pouring out on to the streets.

Without my grandfather, it is easy to imagine a gulf between the football of his century and that of mine. The World Cup, as the sociologist David Goldblatt suggested, “is the greatest regular opportunity for the peoples of the world to look at each other, however bizarre the lens of football makes us appear.” The mythology of the tournament in the last century is bound up in the redemption of brittle men and their precarious countries. It would be presumptuous to imagine that my grandfather saw the same thing, or saw himself in it. For my part, however, I am beginning to see this tournament as an accurate reflection of the world many of us now come from. It is neon-lit, aspirational, and capable of miracles. And yet, to borrow the metaphor from Walter Benjamin, there is a storm driving us backwards into the future; as we go, we are facing the rubble of the past, growing sky-high in front of us.

Who, before 2010, had ever heard the North Korean national anthem outside shouting distance of that country?

Unlike the Olympics, the World Cup was not the brainchild of dreamy aristocrats aiming to resurrect the classical world. Its site was not the city, but the haunted house of the modern nation-state, a fragile, volatile and, for footballing purposes, oddly obliging entity. Over the years, the politics of protest flared up at the Olympics, in acts of defiance, in participation and in withdrawal. The tournament boycotted, and was boycotted in turn, as players and nations used it as a platform from which to declare and debate the question of whether they wished to be part of a comity.

At the World Cup, these questions were largely already answered, and the answer was almost always “Yes.” For example: “Yes, we want you, North Korea.” Who, before 2010, had ever heard the North Korean national anthem outside shouting distance of that country? Perhaps those who had seen the team last in the 1966 World Cup; certainly not the few million who did on that night four years ago as the team played their opening game against no less a behemoth than Brazil (and lost 2-1, an astonishing scoreline). At the World Cup, there are few pariahs.

FIFA, the governor of football, is essentially a mercantile body.

This spirit of accommodation may have something to do with the fact that FIFA, the governor of football, is essentially a mercantile body. A brisk approach to business informed its philosophy of inclusiveness. (The last serious boycott of the World Cup occurred in France 1938: it appears to have been the consequence of a bureaucratic tussle over who got to host the tournament.) In the decades following the Second World War, the Cold War seemed largely absent from the Mundial’s battlefields. Perhaps this was because neither the USA, which had grown indifferent to soccer, nor the USSR, which had come to love it, jockeyed here for power. The great movements for independence and human rights which took place in many African nations after 1950 were also rendered more or less invisible; teams from sub-Saharan Africa had no visibility on the world stage until Zaire qualified in 1974, and it was some years before African teams were able to compete with the established powers of Europe and Latin America.

The Iron Girdle of football looped around the hemispheres in an inconsistent, confusing, but often gratifying pattern of non-alignment. Not everything within this circumference fit exclusively into a first, second or third world. In the days of the radio, the last time in history that football could be experienced in darkness, windows everywhere from La Paz to Calcutta shook with the sounds of matches on the other side of the planet. In these hours, generational alliances and loyalties were crafted. Sometimes this was done in the sophisticated and deeply-felt awareness of political solidarities—the same set of jackboots sounding outside every window. Sometimes it was little more than a voice on the BBC, describing the glistening lassos a man could weave around the ankles of the world if he had the ball at its feet.

In the last years of the twentieth century, the Uruguayan communist Eduardo Galeano began his book, Soccer in Sun and Shadow, with the famous confession: “I’ve finally learned to accept myself for who I am: a beggar for good soccer. I go about the world, hand outstretched, and in the stadiums I plead, ‘A pretty move, for the love of God.’ And when good soccer happens, I give thanks for the miracle and I don’t give a damn which team or country performs it.” The rest of the book proved this to be a disingenuous statement; in fact, Galeano cared very much for the specificities of who was making good football where, and in what time. He dreamed of the Uruguay made possible by footballing victory—a country in which love was repaid with generous and inclusive victory, and the only divisions that mattered were those between Peñarol and Nacional. If good soccer could be made by anybody, in this way, all teams, and all countries, might be redeemed.

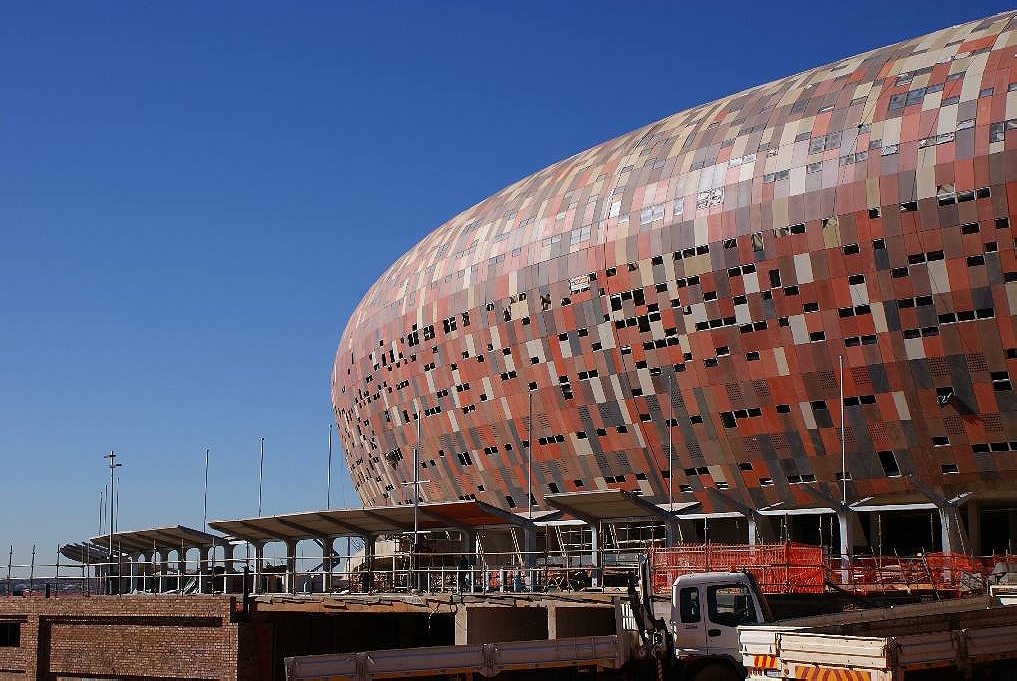

The pharaohs of Egypt built pyramids so magnificent that four thousand years later, some people—admittedly crazy people—wonder if they were built by aliens; some day, the question may be asked of the gleaming stadia that have begun to land regularly, like splendid and impervious flying saucers, amidst the busy, complex and unequal societies of the 21st century. Football may emerge from the people, but its stadiums are dropped on their heads from above. David Goldblatt writes that once, a person could pay as little as one reial and walk into the Maracanã to access the febrile crush of the geral, the standing area between the seats and the pitch. In the new Maracanã, renovated in several stages to comply with FIFA’s Procrustean rules of engagement, the cheapest seats reportedly go for ten times that price. As workers die, buses burn and fighting erupts in the neighbourhoods around these temples of development, Galeano’s vision of a people divided only by the teams they support seems remote indeed.

The alien architects of this particular phenomenon are FIFA, evidently rife with corruption, and nowhere able to better indulge this than in Brazil, from where its longest-running and most notorious president, João Havelange, was elected. Along with its elder sibling, the International Olympic Committee, FIFA has contracted a tendency to earmark the transformational capital of sporting juggernauts for those parts of the world that require “developing.” Like many other world-is-flat stratagems, this has resulted in a tendency to harden many more social and economic boundaries than it dissolves. In many cases in Brazil, this development involved turning stadiums and the areas around them into virtual no-fly zones, destroying local communities in the vicinity, and pricing the poor out of games. (A Maracanã official, explaining the inflation to the Sports Illustrated’s Grant Wahl, said, “This is a cultural process.”)

In 2010, the flashpoint was South Africa; next time, it will be Russia. We live in a decade where the plate tectonics of political economy have caused uprisings that fill the town squares of the world. Over these, and nowhere more than in Brazil, hovers the spectre of a global civilisation of non-biodegradable stadiums overgrown with moss and refuse, like the arenas of the Athens Olympics, a tournament that was held only ten years ago.

And the new century had begun so well. The World Cup was held by France, a fluent, multi-racial team which seemed to embody the fantasy that the society it represented had succeeded in overcoming the rot of colonialism. With new money and cable television pouring through the developing world, the big European clubs were able to do what only Pelé’s Brazil and perhaps Maradona’s Argentina—or Argentina’s Maradona—had done before them, and incur the fierce love and loyalty of people around the world who might never see them in the flesh. In a world awash in capital, new kinds of mobility could be imagined, and old certainties about politics and culture were relaxing. In 2002, FIFA’s tournament travelled to Japan and South Korea, its first Asian host nations; but in a brilliant display of continuity, the cup was won by Brazil. The vocabulary of the World Cup began to catch up with the times: it was a globalised world; Manchester United and Bayern Munich had become global brands; football, too, would become the global game.

Fans in the western world, particularly in the originating societies of modern football, were contemptuous of these changes, but not always for the right reasons. There is nothing petty or boring about the World Cup going to countries with long, if relatively marginal histories of football, played before a population of fans who have rarely been seen or heard from before. But it is precisely in light of this that people wondered at the logic that propped up FIFA’s civilising mission, enshrined in its currently-discarded “continental rotation” policy. Manchester United may have needed an introduction in most parts of the world when they first appeared on TV, but what did FIFA own that was unknown to the world? What did they see out of their helicopters that made them so desirous of re-creating Zurich in Rio de Janeiro? Why must a World Cup be played in accordance of the wishes of those who visit, rather than those who live with its after-effects?

Football has become a catalyst for protests.

Because these questions strike at the same anxieties that have engulfed Brazil in civil unrest in the last year and a half, football has become a catalyst for the protests, with the slogan “Fuck FIFA” or its variants writ large over parts of the host cities. On the one hand, this is not actually something football has wrought. The British novelist China Miéville, who wrote a brilliant essay in 2012 about the depredations of that year’s London Olympics, characterised the distinction acutely: “This is a city where buoyed-up audiences yell advice to young boxers in Bethnal Green’s York Hall, where tidal crowds of football fans commune in scabrous chants, where fans adopt local heroes to receive those Olympic cheers. It’s not sport that troubles those troubled by the city’s priorities.” It is not football with which Brazil’s protestors take issue. It is the things for which football provides cover—the “cultural processes” that entail spending millions on security cameras and “Robocop” uniforms for security guards, rather than improvements to existing public infrastructure or fairly priced transport systems.

Few sports seem so fundamental to the human condition.

As FIFA is never tired of repeating, few sports seem so fundamental to the human condition. When you fall in love with football, you start to believe in its ubiquity. So immersive is this vision that, secretly, we become unable to think of football as anything other than timeless and enduring.

Football will not be extinguished even if the lights go out in these stadiums. The stands may empty out and rust start to eat the railings, but outside, some child with a ball of rags will still be kicking it around. There must be something essential at its core, therefore, that must be worth saving. If we don’t stop loving it, it won’t stop being football.

And yet, it is hard not to feel that, when the tournament finally begins, having been directly or indirectly responsible for sweeping thousands out of their homes, and locking many more outside the doors of football—outside Brazil’s own history—there will be little left inside other than a gladiatorial combat, a ritual of circular logic meant to propitiate those who created it in the first place. Perhaps this is how a sport which was exported around the world in the late 19th century by Europe’s clerks and small businessmen, rather than its sanguinary officer classes, is ultimately militarised.

At halftime in the final game of the World Cup in 1950, Uruguay were huddled in the visitors’ dressing room of the Maracanã, when the team’s captain, Obdulio Varela, centre back and team captain, stepped up and said to them, Muchachos, los de afuera son de palo—the outsiders do not exist. The outsiders, 210,000 of them in the stadium, were screaming for a Brazilian victory. Jules Rimet was sitting somewhere in the throng, carrying gold medals inscribed with the names of Brazil’s players. The score was 0-0; at full time, Uruguay had won, 2-1.

The story must have made little noise outside South America at the time. In Britain, the Guardian carried a small anchor story about the match on page one; most other papers didn’t put it on their front pages at all. It seems unlikely that the game was even broadcast in India, where All India Radio barely reached more than ten percent of the country at the time. Yet when I first heard the story of Varela’s speech, I was immediately taken with it, seized with the impossible conviction that not only had my grandfather heard the match, but he had heard Varela’s very words.

My grandfather and his siblings, especially the boys, were driftwood on the tides of British imperial history. (Years later, his younger brother would shatter a knee playing football on the oilfields of Persia.) Their father had died young, having gone to jail for his involvement in India’s independence movement, and contracted an illness while behind bars. The injustice filled my grandfather with an anger that came out in odd ways through his lifetime; both in his fierce love of the underdog, for example, as well as his deep disgust for the underdog that did not manage to beat impossible odds.

The story of the indomitable Varela commanding his team to shut out the howls of an advancing army of Brazil fans would have been, for him, both a ripping good yarn, and an act that—beyond all sense of proportion—had wiped out a small portion of the world’s elemental sorrow.

It takes a great deal of forgetting to believe in football’s redemptive powers, and one of the things the protests in Brazil have newly underscored to those of us watching is the danger of this forgetting. Yet its healing delusions entranced men like Eduardo Galeano and my grandfather, and in no other footballing endeavour are these dreams more likely to be born and sustained, than at the World Cup.This tournament, too, will mete out small acts of justice that may blossom into great collective optimism. But its audience, too, is on trial; and however we choose to act, one thing is clear—it is only for the footballers on the pitch for whom the outsiders cannot exist. If we are listening to what is going on within the walls of the World Cup’s great tent, it is imperative that we also listen to what goes on outside.

[Header image by: STAFF/AFP/Getty Images]