Once again, Afro-European players are making Europe reexamine its identity.

It isn’t fair. Though Africa has more countries and a larger population than Europe, the continent only has five berths in the World Cup compared to Europe’s thirteen. And they had to fight for that: it was only a boycott in 1966, led by Kwame Nkrumah, that changed the policy that allowed only one spot for either an African or an Asia team. There are all kinds of justifications, of course, offered for this inequality. And it will likely take a long time for change to happen, and then it will come incrementally.

While we wait patiently for institutions to change, however, the world has a way of rendering a kind of justice. Post-colonial migration has created a loophole in FIFA’s global apportioning of representation. This year, there will be two additional African teams in the competition: France and Belgium. If they are going to the World Cup at all, it is thanks to goals scored by the children of African migrants: Romelu Lukaku for Belgium, and Mamadou Sakho for France. I’m not sure if these old colonial powers deserve the help, but they’ve gotten it: Africa has come to the rescue. In fact, it might be worth giving new names to these two football teams: Françafrique and AfroBelgica, perhaps? (If we make that change, though, we also might need to make another: most of Algeria’s team is French born and raised: they similarly represent a trans-regional space, something like North and South Mediterranean-Algiers…)

What does it mean, in these two very different European countries, to depend on Africa on the pitch? And what does it mean for players like Sakho and Lukaku to be standing up for, and standing in for, different layers of belonging and identification?

The night before the game, Sakho made a prediction. “’I’m telling you, I’m going to score tomorrow. I will score,” he told his teammate on the French team, Sissoko. This would be a bold statement for any player, even Ronaldo or Messi, but was particularly bold for Sakho: he’s a defender, and hadn’t scored yet for the French team in his sixteen appearances. His optimism also went against the reigning mood surrounding the French team, which had been heavily criticized—indeed openly insulted—by many journalists and politicians after losing to Ukraine 2-0 in the first leg of their World Cup qualifying series. If they were to qualify for Brazil 2014, they would have to pull off what pretty much everyone would consider a miracle – a 3-0 victory over Ukraine. Nothing about the French team’s qualifying run suggested any hope that this would actually happen.

One of the more high-profile attacks in the days before the game was part of an old playbook established by far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen in the 1990s: accusing the players of being too “foreign” and therefore hating France. After the defeat in Ukraine, his daughter Marine Le Pen, now the head of the Front National party he founded, declared that the “bad results” of the team during qualifying were the result of “ultraliberalism” in the world of football. As her father often had, she conflated professional football and the national team, saying there were too many foreign players—a technical impossibility, since you have to be a French citizen to play on the French national team, and also a false one, since nearly all the players were born in France, and none have been recently naturalized to play for Les Bleus, as happens occasionally in other countries. She also suggested that they stop being paid given how badly they had been doing. “There is a real rupture with the French people. A team can’t be pushed forward only by the desire for monetary gain or individual egos. It has to be carried by an entire people.” But the players on the French team, she opined, had lost the support of their countrymen. They were, she went on “badly raised,” no longer made French people proud, and “openly make fun of the idea that they represent France.”

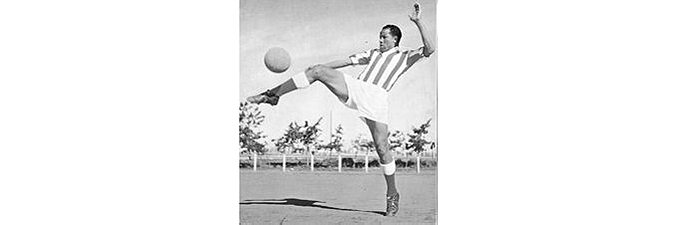

Already in the 1920s and 1930s France had African players, such as the Moroccan star Larbi Ben Barek.

When Jean-Marie Le Pen made similar comments during the 1996 European Cup, his comments had perhaps surprising and unintended consequences, in part because of their bad timing. Though France’s teams had been multi-ethnic ever since they had existed as such—already in the 1920s and 1930s, the teams had North and West African players, such as the Moroccan star Larbi Ben Barek—that fact had never been infused with major political symbolism. But Le Pen’s attacks on the team politicized its players, many of whom responded passionately and angrily to his statements, and also amounted to an invitation to politicians and journalists to embrace the team precisely as a way of rejecting Le Pen. Then, unfortunately for the Far Right politician, a team he had condemned for being made up of “foreigners” and “mercenaries” who didn’t know the national anthem made history, by winning France its first World Cup—on home soil—in 1998. Thanks in no small part to Le Pen, the celebration of that victory doubled for many people as a celebration of the dawning of a new, multi-cultural, France.

Since then, of course, the French team has had major ups and downs. And when it is down, it is really down—the meltdown of the 2010 World Cup being the most prominent and well-known example. For a long time it looked like this year’s qualifying run might be the next stage in a long story of decline into irrelevance. The team’s performance, even against opponents they should have easily beaten, was lackluster at best. There was no hint that the new generation had any chance of coalescing in the way that the generation of Zinedine Zidane, Lilian Thuram, and the team’s current coach Didier Deschamps had, or that they could repeat their surprise run into the World Cup finals in 2006. Though long a die-hard French fan—so much so that I went and wrote a book about the team—I, along with many others, had essentially given up, the persistence of optimism and hope having become simply too painful to sustain.

And then, as so often happens in football, one moment—one ball, one bizarre configuration of attackers and defenders, one action by one player—changed everything. The sequence, in retrospect, has something of an allegory about it. Mathieu Valbuena, the son of a Spanish immigrant to France, deemed too small and short to be a promising player as a young man, now a key player both at Olympique Marseille and on the French national team, sent a free kick directly to the ready feet of Franck Ribéry. The Bayern Munich player—recognizable for his scarred face (the result of a childhood car accident), a convert to Islam who prays openly before games—struck the ball hard towards the Ukraine goalie who, fatally, stopped it but didn’t control it. From the left, Sakho then ran forward and pummeled the ball into the net. His immediate response was to run towards the sidelines, past his coach, to his friend Sissoko. They hugged, and one imagines Sakho whispering: “What did I tell you?”

For long-time fans of the French team, the moment called up another legendary one: the first goal scored by defender Lilian Thuram in the 1998 semi-final match against Croatia. That too, was unexpected—Thuram was a great defender but had never scored a goal before for France. Like Thuram, too, Sakho went on to score another goal later in the game. Thanks to an additional goal by Karim Benzema, France made history with a 3-0 win over Ukraine, qualifying for the World Cup in extremis. The explosion of joy that followed on and off the pitch seemed like it came from another era. The players tossed Didier Deschamps alarmingly into the air, hugged unrepentantly, and—in a performance rich with political meaning—performed a spontaneous, enthusiastic, rendition of the Marseillaise along with the electrified crowd.

Why doesn’t France always play like that?

What had gotten into the French team? And why don’t they always play like that? The turnaround was so sharp and stunning that it was easy to forget just how beleaguered and depressing the team had seemed just days before. But watching the whole scene unfold, you could tell that something had happened within the group. They had, it seemed, decided to turn the match at the Stade de France into a send up of all their critics. In our delight as French fans, it occurred to me, we should probably thank Marine Le Pen, along with various other media critics, for the victory. The team, it seemed, hadn’t really been playing for France exactly. They had been playing for each other, because they were pissed off at what everyone was saying about them.

Along with Sakho, Patrice Evra was one of the pivotal players in the match. His very presence on the pitch, of course, might seem surprising. He was, after all, the architect of the famous strike of French players at the 2010 World Cup. They refused to practice after their teammate Nicolas Anelka was expelled from the team because of an outburst against the coach during a match, the ripe language of which had been splashed all over the pages of France’s sports newspaper L’Equipe. For a while, Evra was exiled from the French team. Anelka has never come back, but Evra’s re-integration at the core of the group under Didier Deschamps was tactically and psychologically a good move. Whatever the media has said about Evra—and they have said plenty—he clearly provides leadership and force on the pitch.

Evra was born in Dakar, of a mother from Cape Verde and a father of Guinean origin. The family moved to Brussels when Evra was a child—his father worked in the Senegalese embassy there—and then to a banlieue of Paris. Sakho, too, is of Senegalese background: his parents migrated to France before he was born, and he grew up in the Goutte d’Or district of the 18th arrondissement of Paris, which has long been a heavily West African neighborhood. These players are part of a larger African group that was pivotal to the French victory, including the young star Paul Pogba, whose parents were from Guinea and Blaise Matuidi, whose father was from Angola. As had long been the case with most of the French team, these players largely grew up in the banlieue outside of Paris. Though there have long been important players of African background on the team—Patrick Vieira, Claude Makelélé, and, in an earlier generation, Jean Tigana among others—they are more numerous today. Whereas in 2006 an important core of the team was Antillean—with Thierry Henry, William Gallas, Eric Abidal, Lilian Thuram, Florent Malouda—today France’s team is, more than ever, African.

Like other French footballers before him, Sakho saw the victory against Ukraine as a symbolic victory for a certain vision of French society. Indeed, the goal-scoring defender sounded very much like Lilian Thuram the day after the victory. In 2006, when France pulled out a surprising and electrifying defeat of Spain during the World Cup, Thuram made a point during a post-game press conference of speaking back to recent criticisms of the team by Jean-Marie Le Pen, who had said that the French coach had “exaggerated the number of players of color on the team” and suggested that, as a result, the population did not feel “represented” by them. “Mr. Le Pen seems not to know that there are black French, blond and brown-haired French,” Thuram said. “What surprises me is that he has been a candidate for president several times and that he doesn’t understand French history. He invited Le Pen to come into the streets to celebrate the French victory with them, and concluded: “We are very, very proud of being French. He might have a problem. But we don’t have a problem. Long live France! Not the one he wants. The true France!”

There was something both strange and beautiful about hearing such sentiments.

After France’s World Cup qualifying victory against Ukraine, Sakho made a similar move speaking to a journalist. Nearing the end of an interview, he asked: “Can I just add something about France qualifying for the World Cup?” Then he went on: “I just want to say that the players in the squad represent everyone in France, the multicultural society of France. When we represent France we know we are playing for the multicultural French nation. We love France and everything that is France. I want the supporters to know that we really fight for that shirt. The cultural mix of France is represented in that squad and we are determined to win the hearts of the fans by fighting really hard for the shirt. It is not a qualification just for 24 footballers in a squad but for the whole nation… France is made up of Arab culture, black African culture, black West Indian culture and white culture and we, a squad that reflects that multiculturalism, are all fighting in the same way and are united behind France qualifying for the World Cup.”

There was something both strange and beautiful about hearing such sentiments. When they were first expressed in the late 1990s, especially after the World Cup victory of 1998, the idea was an innovation: France, seeking models for its inevitably multicultural future, could find them in its successful multicultural team. But given all that has come since—the ups and downs of the team, the scandals surrounding racism at the highest levels of the French Football Federation, the seemingly never-ending aggression directed at players of color on the French team from the far-right—Sakho’s comments seemed almost out of time. And yet they were, in a way, also just right: such statements have always been utopian, but no less welcome for that.

But if France has too many competing visions of what it means to be French—a sort of surplus of nation—then Belgium has the opposite problem: a deficit of nation. What is Belgium, after all? (Full disclosure: I am, though tenuously, Belgian, having left the country when I was three weeks old and returned only for family visits since then). It has been around for a while, certainly, since a revolution inspired by an opera led to independence from Holland in 1830. In military history it is a country famous for its various defeats, usually at the hands of the Germans, and in colonial history, it’s known as the country that offered up perhaps one of the most openly brutal experiments in labor extraction in modern history, in King Leopold’s Belgian Congo. And, for much of the past half-century, it has been embroiled in a seemingly endless conflict between two linguistic groups, Flemish and Walloon. The Belgians can be relatively proud of their civil war, and indeed should consider offering it as a model for export to other countries: no one has, as far as I know, ever died as a result of the conflict. Instead, it is fought through bureaucratic trench warfare over school and voting districts, language policy, and the naming of streets. The venerable and ancient university of Louvain was split as a result of the struggle, with a new town and campus built at Louvain-la-Neuve to become a Francophone campus. An uncle of mine who taught there once told me the story of how the library literally split in half–one volume here, one volume there–like an extremely precise settlement in a gigantic national divorce.

There are a number of places in the world that are nations without states: and some of them have found a kind of representation on the football pitch. Belgium is something different: you might say it is a state without a nation. Actually, it has an increasingly intricate and weighty state, with layers of national, regional and local bureaucracies. At one point in 2010-2011 Belgium didn’t actually have a government for 19 months–541 days to be exact–because it was impossible for a fractious set of parties divided along linguistic and other lines to choose a Prime Minister. The country set the world record for length of time without a government in a democracy (who knew that was a category?), but the joke in Belgium was that it didn’t really matter that much, since the bureaucracy continued to function fine–the contrast with the U.S. in this regard is quite striking—and the politicians finally made a deal because they realized that the population might realize that they were pretty much superfluous.

It has come as a kind of startling surprise to suddenly see Belgium actually take form.

Belgians are many things, beyond the butt of a long run of jokes–good cooks, jovial drinking partners, makers of great beer, ex-colonial power, home to the capital of Europe. What they are not, in any clear sense anymore, is a nation. And so it has come as a kind of startling, and refreshing, surprise to suddenly see Belgium actually take form, in the one place, besides the mind of the King, where it can actually really exist: the football pitch. The fact that players who are the children of African immigrants are among those who are re-inventing the nation makes this story particularly intriguing, and telling.

Several months before Sakho scored his goals in Paris, the Belgian “Diables Rouges,” (“Red Devils”) as they are affectionately known, qualified for the World Cup for the first time since 2002. Along the way they gained many admirers of their intricate, exciting play. But observers have noticed something else about them: there is, rather suddenly, something of the classic French national team of 1998 about this Belgian group. Many of the team’s players—and in fact a number of its key players—are the children of immigrants, or in some cases were born overseas and migrated to Belgium as children. This is the first Belgian team that has featured a group of players of African descent, a reflection of the country’s colonial history and post-colonial migration.

Both goals in the game against Croatia that clinched the qualification were scored by Lukaku, the child of immigrants who came to Belgium from the Democratic Republic of Congo. “These were probably the two most beautiful goals of my career. What is certain is that I’ll remember them for a long time,” the player announced after the game. Lukaku was born in Antwerp, a city that has been a center both for Flemish nationalist and far-right anti-immigrant politics in Belgium for decades. As he was growing up, the sound waves of Belgium and streets of Antwerp were often filled with laments about the danger immigrants were posing to the future of the nation. When Lukaku brilliantly secured Belgium’s place in the world’s greatest sporting competition, spurring celebrations in the stadium and throughout his country, it seemed a bit of justice might have been served.

What was King Leopold’s ghost thinking? The Belgian Congo was, in the nineteenth century, notorious as the site for some of the most barbaric and brutal forms of labor exploitation in Africa, in part because the colony was governed directly by the King of Belgium. The story has been told brilliantly by Adam Hochschild. European imperial conquest in Africa offered up its share of atrocities, of course, but it was the Belgian experiment that probably garnered the most international attention, spurring one of the first international protest movements, which—building on the earlier abolitionist movement—mobilized activists throughout the globe intent on exposing the violence in the Congo. In the late 20th century, while Belgium has engaged in its quiet and relatively peaceful civil war, the Congo region has suffered through decades of extremely brutal conflict, with the former colonial power becoming one destination for migrants looking for an escape. This history lurks in Belgium: on the outskirts of Brussels, for instance, is one of the strangest and most enthralling monuments to colonialism you will ever encounter, the massive Tervuren Museum which houses an enormous collection of zoological and cultural materials from the Congo. During recent years, curators and artists have sought to find ways to address the colonial past from a different perspective—next to a wall listing the names of Belgian colonial troops who died in the Congo, one artist projected a series of crosses with the question “Where are the Congolese names?”—and there is currently a large-scale renovation and reconceptualization of the museum under way. Still, like France, the country badly needs a serious engagement with its colonial past.

The team has largely been greeted with enthusiasm by Belgian football fans.

Will football help make that happen? Lukaku is one of several players of Congolese background on the Belgian team. Christian Benteke was born in Kinshasa in 1990 but came to Belgium as a child and grew up in Liège. And team captain Vincent Kompany’s father was a migrant from the Congo as well. Players of Congolese background, though, are just one part of this group. Mousa Dembélé’s father is from Mali, while Axel Witsel’s father is from Martinique, thus connecting him to a long and venerable tradition of European footballers of French Antillean background. Marouane Fellaini is one of several players of Moroccan background on the team. And though there has certainly been some grousing from various quarters about the multi-ethnic nature of the team, it has largely been greeted with enthusiasm by Belgian football fans who, above all, are thrilled and relieved to see their team back on the international stage.

An enthusiastic article about this team from 2012, entitled “These Red Devils From Elsewhere,” celebrated this diversity and argued—as others have—that it has been the source of Belgium’s success. A Belgian coach named Sahid explained that younger players of immigrant background found themselves inspired by the presence of players from diverse backgrounds on the national team: “Today, thanks to the perfect integration of footballers who are the children of immigrants into the national team, many young Maghrébins and Africans understand that the system does not lock them out. Everything is a question of talent.” And young player in an academy in Antwerp—where Lukaku was born and trained as a young player—announced: “Me, too, I want to become like Lukaku. My parents are from the Congo. But me, I’m Belgian. Belgium is my homeland. So I’ll wear the jersey of the Red Devils.”

Will players like Lukaku and Kompany end up becoming the kind of symbols for Belgium that Lilian Thuram and Zinedine Zidane once were for France? That will depend on whether the team does well in the World Cup, and also on whether the players themselves opt to present themselves as symbols. Kompany has shown some signs of being willing and able to do so. He tweeted about the French election—noting at one point that he was doing so because it was a lot easier than talking about Belgian politics—and showed a sense of humor while doing so. “Two candidates for president: @fhollande doesn’t like the rich and @NicolasSarkozy doesn’t like the foreigners… I’d be in trouble there!” But like many French footballers, most notably Lilian Thuram, Kompany criticized Sarkozy, calling him “an unstable two faced character” whose “politics are dangerous as it’s based on exploiting the fear of people.” Kompany also pleasingly models multilingual equanimity on Twitter, sending out messages in French, Flemish, and English.

Lukaku and other players have been less vocal about politics. But in a sense their very presence represents a kind of politics, or at least a kind of promise for a different kind of model. The fault lines of the conflict in Belgium have largely been about language, though language has also served a proxy for those who have made claims about cultural and ethnic difference between Walloons and Flemish people. But what is Lukaku? What is Kompany? What is Fellaini? Walloon or Flemish? For younger Belgians, many of whom consider themselves as European as Belgian, and who are increasingly fed-up with the encrusted conflict they have grown up with, the national team can stand as a symbol of something beyond all this, of something new.

When they are on the pitch, fast and loose and intricate, a team with joy and youth–and in those great red and black jerseys–the Red Devils make you want to be a Belgian. This summer, especially if the team does well–as it certainly has the potential to do–the virtual population of this little, beleaguered country in Europe may well expand exponentially, at least for a time. Football can’t change the world, or even a nation. What it does, sometimes, is offer a little tilt to things, hinting—through what is before us, on the pitch–that other worlds are worth imagining, even if only for an instant.