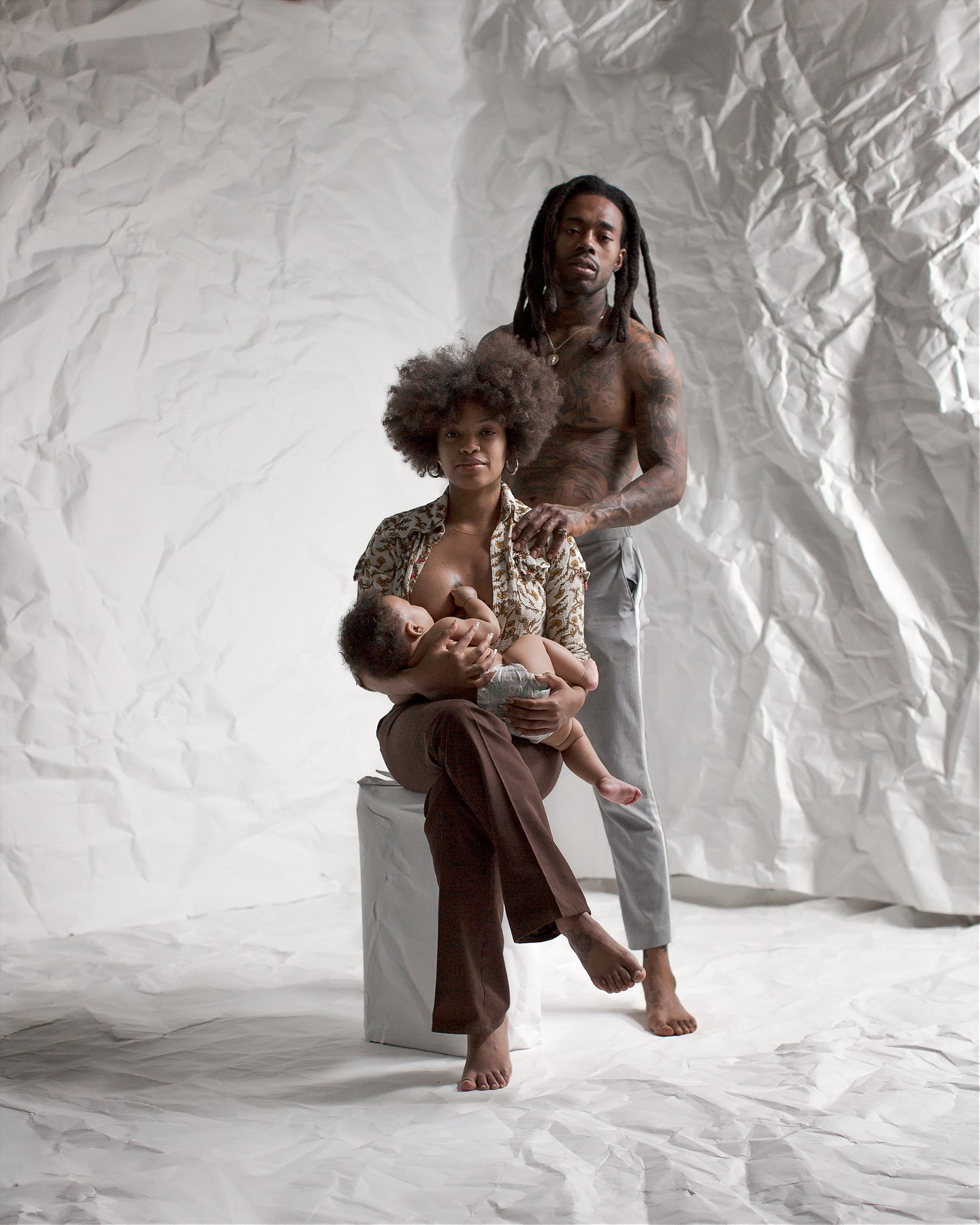

Photographer Cam Robert deconstructs the narrative around black masculinity in his intimate, surrealist portrait series.

Who gets to be an individual? The answer should be simple but it seems to get murky when it comes to black men. With his project “Pastel,” Brooklyn-based visual artist, photographer, and filmmaker Cam Robert explores the complexities of this question. The ways in which his black, male subjects inhabit their surroundings challenge paradigms about the relationship between race, gender, and identity. His soft, surreal images explore the spectrum of black masculine identity, with the ultimate message that black men, like everyone, can be anyone.

Robert talked to Roads & Kingdoms’ Irene Jiang about rewriting the narrative of black identity, how the Pastel project came together, and his passion for film.

Irene Jiang: How’d you get into photography?

Cam Robert: I’ve always had a passion for it. When I was younger, I would make videos and do little photo things with my friends and when I was 12, 13, I would volunteer at my church as a cameraman. When I turned 18, I bought my first camera and was just was obsessed with it. I kept on working on it, but I didn’t know I could actually become a photographer in the sense I am now. I thought I would have to do it through another avenue like being a newspaper photographer or something. But I kept getting drawn to the more creative fine art side of things and it kind of evolved.

Jiang: How did Pastel come to be?

Robert: It created itself very organically. I didn’t know how to do studio photography or lighting because my background is more in photojournalism. So a lot of my work has a very natural light-leaning, kind of gritty aesthetic. Ultimately, my goal is to become a director, so I knew I would have to learn lighting. Pastel started when I was practicing in the studio trying to figure out how lighting works. Over time, I started thinking about how I could make something with a deeper message. I was coming into fruition as a young black man, figuring out my place in the world. I was doing random photo shoots, and I was always seeing these projects that were about black identity, male identity, but they were always through the lens of showing the softness of black identity—which is cool. That’s of course great, because society views black men within a box. But I thought the way it was being presented, like showing a black man with some flowers in their hair or wearing “feminine” clothing and those sorts of things, was very limiting. It’s cool that we’re seeing that side of the spectrum, but even if you’re going to talk about these things, you have to recognize that identity is on a spectrum. It’s not one or the other. You can be this and that, simultaneously.

So I wanted to create a project that winked at the idea that having a conversation that hones in on this small aspect of a person’s identity is kind of surreal, to begin with. So that’s where the surreal aspects of Pastel came from.

Jiang: How did you choose the objects that you use in your scenarios? Do they have any sort of symbolic significance?

Robert: I created a mood board of ideas and things that inspired me that I’ve seen in the world. I’m an avid believer in the whole idea that the greatest artists steal from other artists. So, I would see an idea and I’d think about how I could build on that and bring it into my project and make it my own.

I saw someone use the crumbled backdrop in some photo shoot, but it was just the backdrop. There wasn’t an actual 3D space. So I was like, okay, I like where they’re going, but what if we create a whole world that’s based on this idea and really build it out. So the subject is living within this crumpled paper space and it’s kind of juxtaposed with the portrait of the mother, who’s caring for her child and breastfeeding her child. and then you have all this confusion and erraticness around them. A lot of the ideas were sparked by another.

Jiang: Are there specific stereotypes about black masculinity that you wanted to break?

Robert: Well, I knew I wanted to touch on fatherhood and the stereotype of fathers not being present in their child’s lives because that’s a myth. Aside from that, I don’t think there’s anything specific as far as stereotypes that I wanted to break. It was more so just rewriting the narrative as a whole of what black masculinity or identity is. I just wanted to bring attention to the fact that on TV, white women, white men can be literally anything. You don’t see projects breaking down the stereotypes of white masculinity, because if someone made a project like that, people would be looking at it like that’s crazy.

People are who they are. If you see a black person who lives in India, their perspective on life is completely different than my perspective. There’s no single picture. It’s absurd that we try and create one because everyone is complex. I know some people who are the most hood people, and then they listen to Beyonce. That’s not weird. That’s normal. Who doesn’t like Beyonce?

Jiang: How do you feel about the response you’ve received because of this project?

Robert: This is the first photo project that I worked on by myself. I conceptualized it, I shot it, I did all the lighting by myself. It’s just literally my creativity. No one else’s, just mine, and people liked it. It’s a cool feeling because as an artist you’re going to have hella doubt. Especially with social media and everything, it’s so easy to doubt yourself and think you’re not good enough or your ideas aren’t good enough, but it’s not true.

So it’s been a great feeling. The fact that anyone cares enough, It’s definitely been helpful in my creative growth. I value my ideas more now. It’s so easy to like get caught up and doubt yourself, but you just got to realize sometimes your ideas are really good, sometimes they’re not, but more important than that is just the fact that you’re getting your ideas out there and you’re making stuff because that’s a part of the creative process itself. Creativity’s a two-way street. It’s literally consuming the world around you and ingesting it and letting it ferment within yourself and affect you and then pushing it back into the world, but through your lens and through your perspective.

Jiang: You mentioned that you are now looking to get into directing.

Robert: Yeah. Funny enough, I love photography but I wouldn’t say it’s my passion. The creative process after the photo shoot, it’s not too crazy, at least in my experience. Maybe constructing the perspective or the way you want to present the photos, that’s grueling and that takes time. But after you take a photo, what you have is essentially what you have. But with film, it’s just so much more involved. You blend so many different mediums within it, whether it’s the sound, the actual shooting of the film, the narrative, the writing of the language within it. It has so many different elements in so many different mediums. And I think that’s so cool.

Jiang: Are there any projects that you’re working on now?

Robert: I’m writing a short film right now. I don’t want to give away too much, but it plays with this idea of a kid’s daydreams and aspirations and parallels an older person’s memories that are starting to fade away. So it’s kind of blurring the lines of oh, was this a memory, or was this kid’s imagination going crazy? It’s very meta, but it’s gonna be cool. Trust me.

Jiang: Okay. What is the impact that you hope to have with your work?

Robert: I don’t know, I haven’t really used that as my gauge. If anyone’s inspired by my work, then cool, but that’s not my goal in life. In life, you’re going to inspire people, because it’s just how life works. You look up to people who are doing what you want to do. But I don’t make work in the hopes of inspiring people. I feel so selfish for that, but also, we have one life to live. I’m going to try and live life the best way I can and be the happiest I can while moving through it. If there’s one thing I can leave behind or impact it’s if my stories can open the door and create conversation, create more inclusion as a result.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.