Photographer Kevin Bubriski’s new book gives us a deeper look at Syria before the war.

There is a stillness within the pages of Kevin Bubriski’s latest book “Legacy in Stone: Syria Before War.” In contrast to the chaotic images that have inundated newspapers and social media feeds for the past seven years of war, Bubriski’s one hundred frames—characterized by sharp angles and light play—feel slow and quiet.

There are no bombs or weapons of war, and the pages are free of today’s scenes of destruction and sorrow. Still, Bubriski’s visual narrative—portraits of smiling Syrians and stacked stone—creates a pervading sense of loss, which comes from the knowledge that only a few years after these images were captured, much of the subject matter no longer remains.

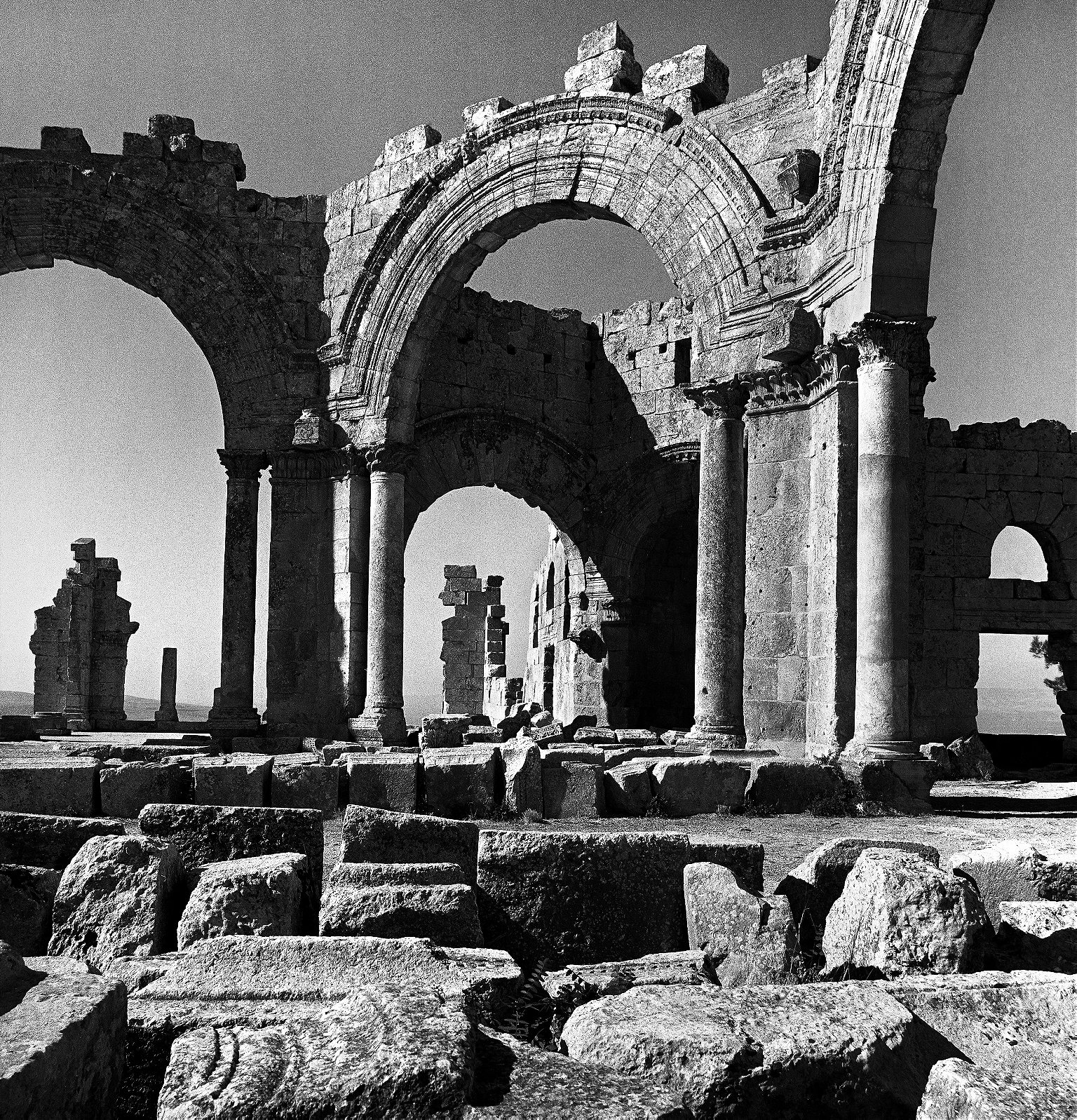

Bubriski studies the 5th-century Church of Saint Simeon’s intricate arches, damaged from being passed between the control of different militias and by Russian bombardment. He captures Aleppo’s ancient souk passageways before they burned down, and the city’s 13th-century citadel before it was hit by missiles and mortars. The images showcasing Syria’s layered, Levantine history were taken while Bubriski was there on assignment in 2003. His book is as much about shadow and light as it is about memory and war—a record of what once was.

Bubriski spoke to Roads & Kingdoms from his home in Vermont, where he’s an Associate Professor of photography and the co-director of Documentary Studies at Green Mountain College.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did this work get started?

Kevin Bubriski: The initial inspiration to go to Syria came when George W. Bush had just started the war next door in Iraq. I’d never been to Iraq or Syria or any part of the Middle East, really, other than Turkey and Egypt. The reason to go to Syria was to get close to the conflict, but not be in the conflict. I wanted to show regular people, normal lives.

There was a lot of demonization through media back then of certain parts of the world and certain demographics. My friend, Lou Werner, and I had done a number of assignments in places like Mali, Niger, and Pakistan. We just thought, let’s go to Syria and do a story about people. The assignment was to photograph the souk of Aleppo, and do portraits, and tell the story of the people through the photographs and their stories.

R&K: What led you to photograph the archaeology specifically?

KB: After the assignment work in Aleppo, I learned from a few friends about the Dead Cities. I started researching them and I got Ross Burns’ book, “Monuments of Syria.” It just opened up this world for me—this incredible place of deep history with all of these somewhat abandoned settlements from early Christianity and from the Byzantine period. That’s what ended up keeping me in Syria for a while.

R&K: When did you start planning this book?

KB: I created a mock-up of the images as much as seven or eight years ago before the war. I went back to Syria with my wife for her work in 2009. She set up the first study-abroad program between Damascus University and Williams College.

That was an amazing time in Damascus. It was just beautiful. There were all kinds of young, European students studying Arabic. The Umayyad Mosque was filled with people from all over the world, enjoying the space and sharing time together. But at that time I wasn’t actively pushing to get the book funding and produced. Then once the war started in 2011, lots of people were saying, “Kevin, you’ve got that collection of photographs from Syria. Publish it. This is important work.”

Then a number of things slowed down the momentum but eventually, the Henry Luce Foundation saw the body of work and said they’d want to help publish it. They gave me a special project grant that was enough to cover half the cost of the book production. Then it was a matter of me going out and gathering up another chunk of financial resources. PowerHouse Books had been interested in the books for years, but I just hadn’t mobilized the resources until last year.

R&K: Why did you choose to photograph so much of the architecture?

KB: I would say the subject matter demanded it. When you go to remote parts of the Middle East, how can you not? For me, as a photographer, how can I not spend time just sitting among these beautiful architectural masterpieces? Then the sunlight and the interplay of positive and negative space, and architectural form, and the structure and texture of the stone. It’s a field day for someone with an eye, and a camera, and back in those days, film.

I put images out on Instagram at least a few times a week. Yesterday, it was the same thing with cross-country skis on my feet in the snow, stepping a little bit this way, that way to where the trees, the snow, the branches come together in a significant composition. That’s really, that’s what I was doing, whether I was at Palmyra or Saint Simeon. There’s a matter of moving myself in relation to this beautiful architectural landscape. That’s all one can really ask for as a photographer.

When I was making these pictures, I wasn’t thinking in terms of what might be lost in the future, but just documenting the beauty of what I found.

R&K: Do you still photograph a lot?

KB: I do. I was out yesterday. We had a nice snowfall up here in Vermont. Very cold, single digits, but I went out with my skis and my phone, and took a bunch of photos of the newly fallen snow. It was just beautiful. So much of what makes life interesting for me is the visual encounter, and the camera takes me deeper into the visual encounter. It’s one thing to cross-country ski through newly fallen snow, but then if I have my camera, even the phone, it’s a reason to stop and to really see something in a particular way with more intentionality.

R&K: How are you using social platforms like Instagram as a photographer?

KB: I love putting the images out there. I put some images up last night of just wandering in the snow. Instagram, on the one hand, is such a brilliant, wonderful platform, and yet, it also eats time. I get a weekly alert now on my phone telling about my screen time. It’s just like, “No. I should be reading books. I should be out in the woods.”

On the other hand, it is unbelievable the way we have access to see what’s going on in different places, but it also can, as I said, eat up our attention. Also, I don’t think it’s healthy seeing how many likes one gets.

R&K: Are you trying to go back and revisit these places?

KB: I would love to. I’m going to leave my teaching position at the end of the academic year, so I’ll have more freedom. There are other questions of safety and I’m not somebody who’s spent time in areas of conflict. So if the coast is clear, if there’s a way to be in Syria and go back to the Dead Cities around Idlib and elsewhere, I would love to. Again, just to see what’s there.

I’ve been in touch with groups monitoring the damage and heard about the Russian bombing of Saint Simeon. I knew that it was damaged but I thought it was by ISIS. I didn’t realize that the Russians then bombed it as well. I have heard that the Aleppo citadel withstood quite a bit.

R&K: Do any images from the book stand out to you?

KB: The image at the North Gate at Resafa was just pure magic. My guide, Abdullah, had been taking me through the Dead Cities and elsewhere. In this picture, the sun was just about to set. It was in a position that it came through a slit in the large doorway of the citadel town of Resafa. You can see that band of light that bisects the column.

I was so excited. I remember telling Abdullah, I said, “Look at this. Look at this.” I don’t know if he understood what I meant, but photographically speaking, what I saw happen to that column due to the light, that was just brilliant. It was just a great moment to be there with a film and a camera. That’s photography.

Think of Cartier-Bresson catching the guy jumping across the puddle right before his heel hits the water and obliterates his reflection. That’s photography. Josef Koudelka capturing the kid in an angel costume, riding a bicycle down the street. Things like that.

That’s what I felt when I made this picture.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.