Didier Kassaï uses his cartoons to comment on the Central African Republic’s political instability and the lives affected by it.

At times, illustrator Didier Kassaï feels the weight of exhaustion when he thinks about his country. The Central African Republic hasn’t been able to rest since a Muslim-majority rebel group, known as the Seleka, took power in March 2013 through a coup and put Michel Djotodia in power, leaving dozens of people dead in the process. A Christian-majority group, the anti-balaka, mobilized themselves in response, and the two groups have clashed ever since. The government has very little power outside the capital of Bangui, and other armed groups have formed across the country. That, along with the displacement of large portions of the country’s population, has contributed to the continuous instability of the Central African Republic.

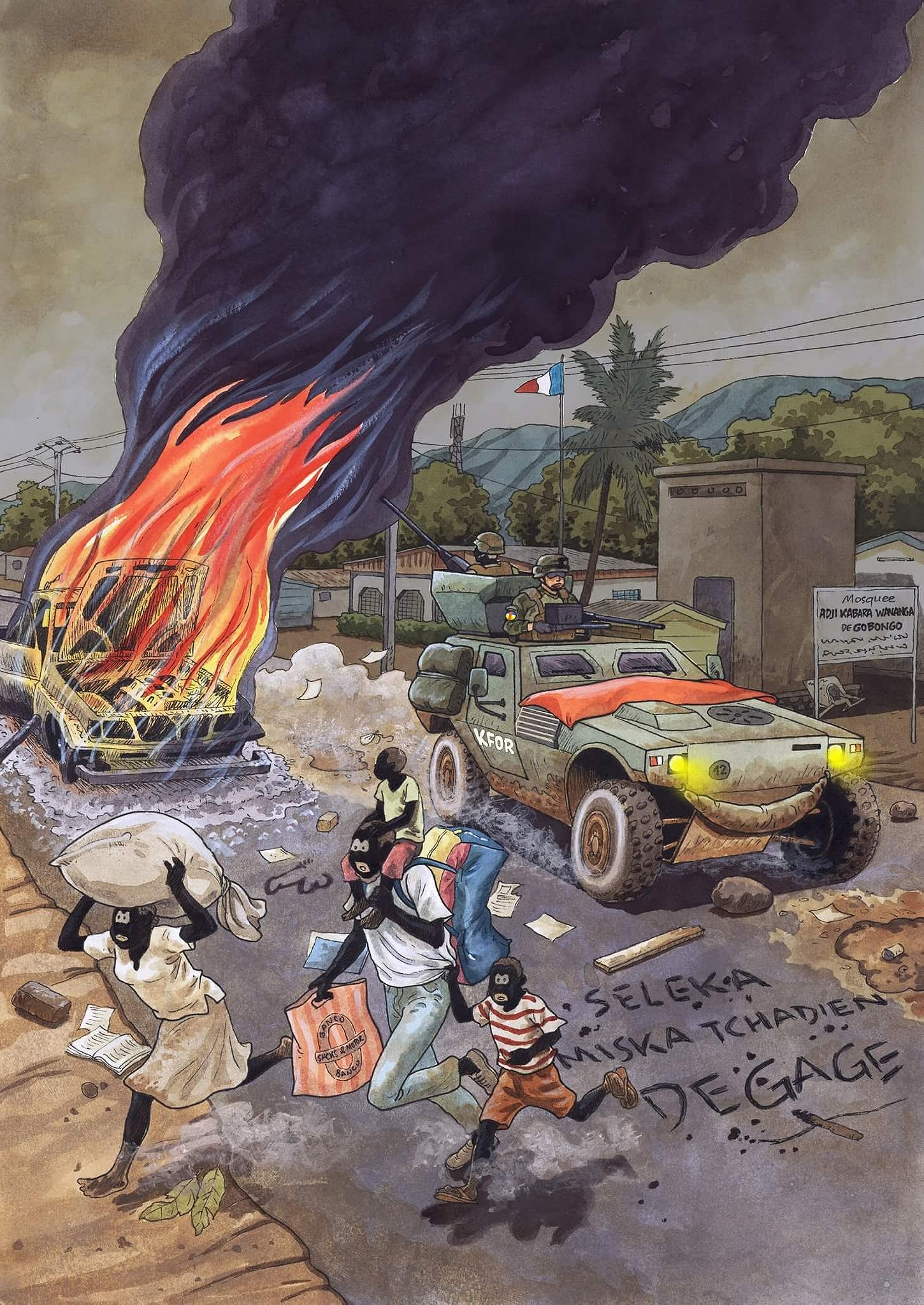

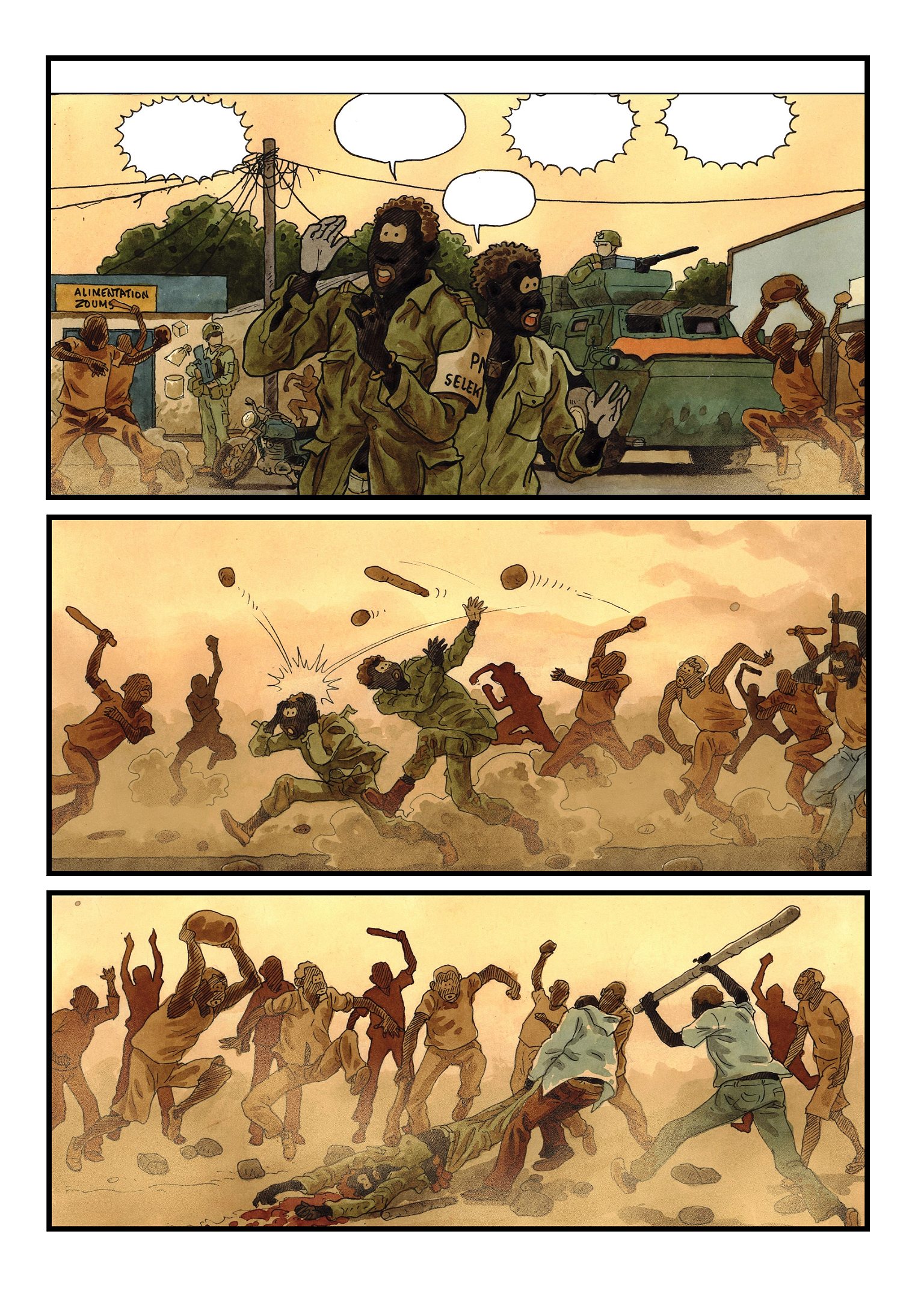

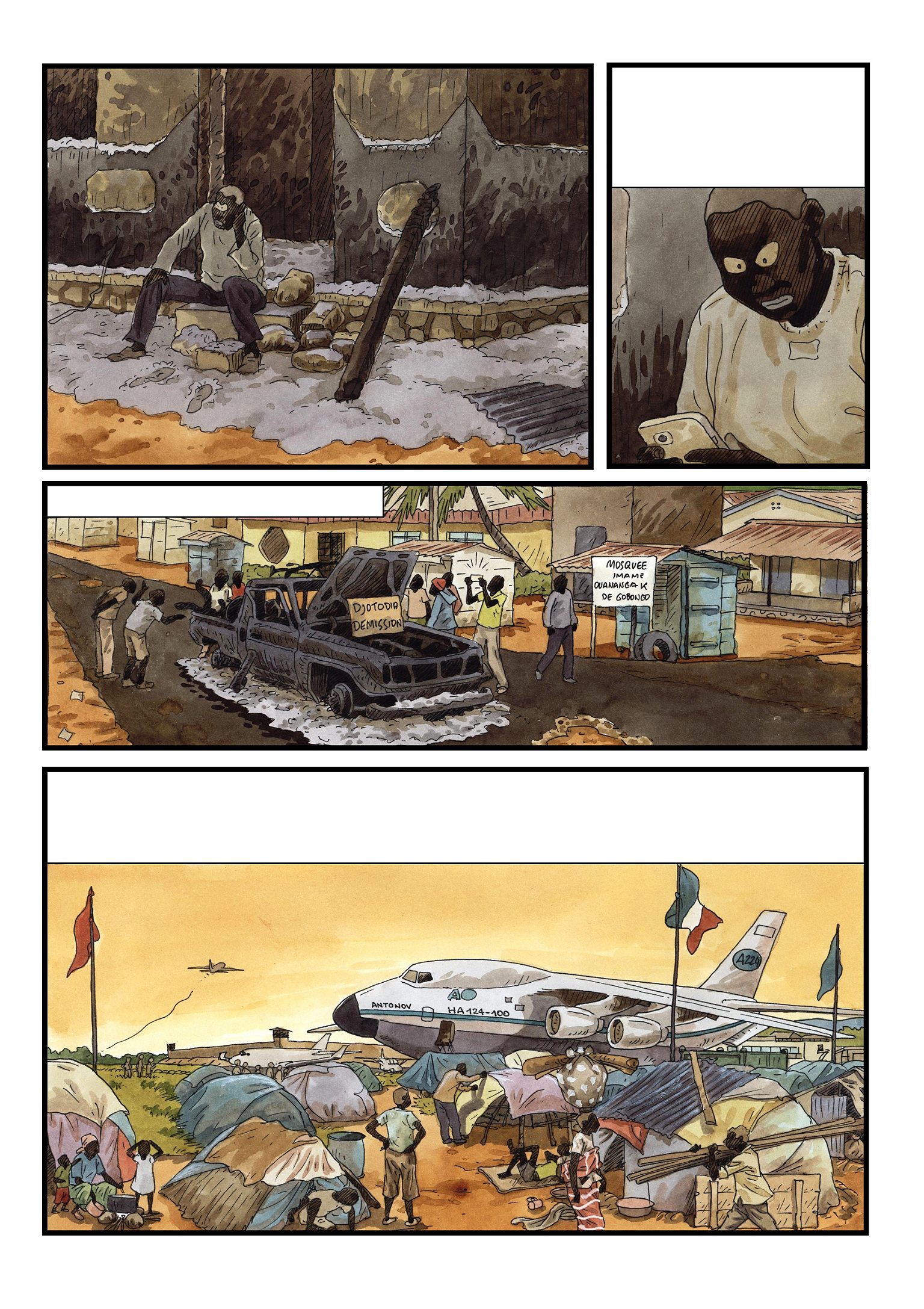

But rather than take up arms as others did, Didier decided to grab the tools of his trade and document the conflict, despite the potential risks. The cartoonist created the comic book, Tempête sur Bangui (Storm on Bangui), in which he illustrates the violence and daily uncertainty residents of the Central African Republic have experienced since former President Francois Bozizé was ousted from power.

Even though he would never call himself a journalist, Didier’s work as a cartoonist shines a light on the everyday people suffering the most from the ongoing crisis. Didier spoke to journalist Paul Lorgerie for Roads & Kingdoms about his work and what he sees for the future of his homeland.

Paul Lorgerie: How did your illustration career begin?

Didier Kassaï: Drawing runs in my family. My mother is an amateur illustrator. She passed the illustrating virus to me and my five brothers. When I was a child, I would draw comics on the floor with a piece of chalk or coal. Then I got lucky. In 1998, I was in Bangui and I had heard about a contest being held for professional illustrators and the prize was an internship in Libreville, Gabon. The director of the contest told me they wouldn’t be able to accept me because I was an amateur illustrator. But I persevered, and I managed to convince them that I deserved the internship. That is how my career began.

Lorgerie: What was it like to try and start a career as an artist in the Central African Republic?

Kassaï: My father was a postman, and he was initially against the idea of me being an illustrator. But when my father became unemployed, he understood the value of what I was doing since it allowed me to make money. When I left my hometown of Sibut for Bangui, I was 17 years old and I had to find a job. I was the one who had been paying for my brother’s studies since I began to work when I was 12 years old. My uncle, who was my guardian at the time, was no longer giving me food since I had stopped my own studies, so I was working as a bricklayer to get by. But mostly, I was drawing T-shirts for 150 Central African Francs ($ 0.26) each.

Lorgerie: Eventually, social media helped you become a well-known cartoonist, right?

Kassaï: Yes. At first, I only published my drawings on my blog, as well as on Facebook. When the crisis erupted in late 2012, I decided to do commentary on what was happening through my little cartoons. The number of friends that I had on Facebook rose from about 200 to a 1,000, but my concern was not the community that I could reach on social media. Not everyone has access to the internet, so I decided to make a book of my illustrations to reach more people.

Related Reads

Lorgerie: What motivated you to document what was happening in 2012 and 2013?

Kassaï: I noticed that at the beginning of the crisis, there weren’t very many journalists covering the conflict. The ones who were covering what was happening, couldn’t reach some places I could. The people they tended to interview were chief members of Seleka or other officials, rather than members of the population who were suffering. The information being reported about the conflict was unbalanced. What was being reported did not show the reality that we were living. Since my reputation as an illustrator was growing on Facebook and on my blog, I decided to publish short, illustrated stories about the conflict from my point of view, so that I could give a voice to the average citizen.

Lorgerie: Did you consider yourself a journalist while you were doing this work?

Kassaï: I was doing journalism without daring to say that was what I was doing. I didn’t necessarily want to do their job. I was just doing what I could to tell important stories.

Lorgerie: How difficult was it to publish those stories in such an unstable environment?

Kassaï: It was hard. I live in the northern part of Bangui, which was, in 2013, considered to be a stronghold of former President Francois Bozizé. Seleka members were launching attacks every day, and gunfire was a part daily life. I had to protect my family and myself. So we hid, and we ran away many times. My house was looted, and set on fire during separate incidents. But each time my family and I fled, I took a little piece of paper and a pen with me. I got used to working with just that. It was easier to take those small items with me, and it was easier to scan my illustrations in cyber cafés. That is how I created Tempête sur Bangui Vol. 1.

Related Reads

Lorgerie: What was the people’s collective state of mind when the Seleka took over?

Kassaï: Not bad. People were fed up with Bozizé’s regime, which began in 2003 and ended with the coup. I and many others thought, at the time, that the 2013 coup was necessary. We thought the violence would end quickly. We thought that it would take only weeks, maybe months. But it has lasted for years. We started to regret the removal of the former president. We started thinking that Bozizé was not that bad, and some of the people nostalgic for the Bozizé era decided to join the anti-Balaka.

Lorgerie: In Tempête sur Bangui, civilians and armed groups have no faces, only eyes and mouths. Why is that?

Kassaï: At first, I wanted to create a black-and-white comic book. When you draw a war, you don’t need any color to illustrate it. War is ugly. Then I thought that colors could soften the harshness of what is happening here. I believed this war had no face. I couldn’t recognize any of my countrymen and women back then because everybody was spreading messages of hatred, so I gave them only eyes and mouths.

Lorgerie: But the caricature style gives a little bit of humour to the story, which is really dramatic.

Kassaï: Yes. And I tried to put in a lot of humor, especially in the first volume. I don’t like to draw corpses and people getting killed. I already talk about it. I don’t want the reader to be shocked. And when you draw violence, you can’t draw flowers. Humor helps.

Lorgerie: The first volume talks about the Seleka arrival in Bangui. What will the second volume of the comic book focus on?

Kassaï: The first volume focused on what happened before, during, and after the Seleka raid on Bangui in March 2013. But that is only a little part of the story. The second volume of the comic book starts with how the anti-balaka came to be, and their role in the conflict. Without the Seleka, there would never have been an anti-balaka. That is what the second volume focuses on.

Lorgerie: So how would you describe the anti-balaka group?

Kassaï: Today, they are mainly bandits. Before, they were revolutionaries to me. People rose up because their communities were targeted. They were hunted, their villages were set on fire, and they have lost a lot of family members. They had to defend themselves. It was legitimate. But then their fight became political. Some of them thought they could take power. And the December 5, 2013 anti-balaka attack on Bangui was not the fault of all of the people who carried out the assault. I personally believe they were manipulated by their superiors. Some of them who were part of that attack told me they were simply mercenaries. Some people say they were promised a job with the Central African Republic army, or money if they took part in the attack. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out, and the outcome was a massacre of civilians.

Lorgerie: A lot of media have talked about this conflict as a religious conflict. What to do think are the roots of the continuing situation?

Kassaï: I don’t think this is a religious conflict. I tell people that if this is the case, my family would have been torn apart. I am a Christian. My wife is a Muslim. Our children go to church, as well as to the mosque. I have never had any problems with my wife’s family. In reality, this is a political and economical conflict. This is the conflict of people who want to take power and the conflict of people who use chaos to loot the country’s resource. This is why these armed groups maintain this chaotic situation.

Lorgerie: What source materials do you use when creating your illustrations?

Kassaï: I listen to the radio a lot. During the events start of the conflict, I listened to Radio France Internationale (RFI), 24/7. There is also Ndeke Luka, a national radio station, which has correspondents dispatched throughout the country. They were giving the voice to the witnesses and victims of violence. Every day they were broadcasting people’s stories, and it gave me the opportunity to know what was happening out of Bangui. Each time I listen, I took notes. Then I started to interview citizens because I wanted to hear directly from the people.

Lorgerie: In Tempête sur Bangui Vol. 2, you place yourself as the main character instead of someone else. Why did you make that decision?

Kassaï: Yes. In every book, there is the main character. This time I used what my family and I experienced as a concrete example of what was going on in my country.

Lorgerie: What do you think about the current situation?

Kassaï: Sometimes it is getting better, sometimes it is getting worse. And I have no idea how the situation will evolve. The Central African Republic is divided in two. One part is led by the government, and the other is led by armed groups. Each time the government makes a decision, it is disputed by the militias, which sparks violence throughout the country. The future is very unclear.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.