On March 19, pizza chefs and pie aficionados from around the world will gather in Sin City for a three-day exhibition. Most pizzaioli come here to network and expand their businesses—but some, like Nino Coniglio from Brooklyn, see it as the ultimate quest for glory.

Over 10,000 people come to Vegas each year for the International Pizza Expo. They come from places like Custer, South Dakota, and Appleton, Wisconsin, and Gainesville, Florida, and Pickering, Ohio. There are Italian bakers who travel the world making pizza on the competitive circuit: Vegas, Atlantic City, Parma, Hong Kong. There are Korean dough tossers who train for months to get their acrobatic routines just right. There are families like the one I met in the Stanislaus Food Products booth—400 square feet of scaffolding and Astroturf dressed up like a countryside Sicilian trattoria, where waitresses served plates of antipasti and carafes of red wine while a live band performed the soundtrack to The Godfather.

They come to see Dan Collier, the mustachioed-and-mulleted entrepreneur who started delivering pizzas 20 years ago—and now owns eight shops across Ventura County, California. They come to watch Graziano Bertuzzo, the gentle Apulian maestro who has spent the past 40 years perfecting the alchemy of a weightless, celestial crust. Pizzaioli from five continents now travel to the southernmost tip of Puglia just to enjoy his tutelage. Then there is Tony Gemignani, Bertuzzo’s gumptious American counterpart. With 12 world titles, five successful restaurants, three cookbooks, and a signature olive oil, Gemignani’s white pizzaiolo jacket was covered in more sponsor patches than a three-time Nascar champion.

Then there’s Nino Coniglio: the self-proclaimed no-bells-no-bullshit Brooklino who talks a tough game but treats his craft with an unmistakable tenderness that endears him to his fellow pizzaioli. Coniglio, 31, is stocky and brash and a little too cocky for his age. Every hair on his head has migrated to his beard, which is curly and bushy and fire engine red. His arms are covered in tats—the SPQR of the Roman Republic, the three-legged triskelion of the Sicilian flag, two slender hands clasped in prayer, with a rosary dangling below. A faded schoolboy cap covers his hairless head and a tight-fitting Brooklyn Athletic Club jersey encases his distended belly. “Some old Italian guy named Vinny died in Bensonhurst,” a colleague once said. “God just recycled the soul and out popped Nino.” Nevermind that Coniglio, née Ryan Coniglio, is the son of an IT specialist, raised not in Brooklyn but in a middle-class neighborhood in Central Jersey.

I met Coniglio at the 2017 Pizza Expo through his business partner, Aaron McCann, while waiting in line for beer. In a sea of paunchy older men carping about the perennial industry woes–the trouble with franchising, the trouble with couponing, the trouble with romantic entanglements between employees–McCann looked rangy and cool in chucks and a leather jacket. He talked about Williamsburg and small batch whiskey. It was his first time at the Pizza Expo, too.

McCann met Coniglio over five years ago when he was opening up his first pizza shop in a vacated Chinese joint on the ground floor of his apartment building in South Williamsburg. He needed a chef, put out a Craigslist ad, and got several dozens of resumes. Coniglio’s stood out for including just one line: “check me out on Google.”

“I didn’t bother reading any resumes after that,” McCann told me. He had been mesmerized by Coniglio’s YouTube videos, his Today Show appearance, the New York Times piece that said he “handles dough like a Harlem Globetrotter.” The story of a loud-mouthed kid who rose from mopping floors at the neighborhood slice shop to the cusp of local celebrity had resonated with him, too. “The guy’s got to be totally nuts, I thought. But he must be great at making pizza.”

McCann’s intuition paid off. Thanks to Coniglio’s inventive spin on old school, New York-style slices (dough made with wild yeast, toppings that ranged from basic cheese to kale and soppressata baked in a triple-decker Vera Forna gas oven and served on paper plates), Williamsburg Pizza, within five years of its 2012 opening, had expanded into four brick-and-mortar locations. Coniglio’s pizza made “Best Of” lists in New York magazine and Food and Wine, and earned comparisons to institutions like Grimaldi’s and Di Faro’s. At the 2016 expo, Coniglio was anointed “Pizza Maker of the Year” for baking a show-stopping composition of wild mushrooms, homemade mozzarella, smoked scamorza, rosemary, and pine nuts. That title qualified him to compete in the high-stakes baking championship held at the end of the week, known as The Best of the Best.

“It’s like Highlander,” Coniglio boasted. “I’m going up against the only people who’ve won what I won.”

In an Uber en route to a private party celebrating the first “certified” Neapolitan pizzeria to open in Hawaii, Coniglio described his latest project. He was launching his own pizza media channel—the “Brooklyn Pizza Crew”—that would produce slickly edited how-to videos and shareable documentary shorts.

“Like those Munchies or Tasty style videos,” Coniglio said. “But instead of filming them in the studio and slapping a lot of fucking bacon on everything, we’re going to go out and do them with real chefs, you know what I’m sayin’?” he said. “Real Brooklyn guys who do things the old school way.”

In Coniglio’s eyes, there was no competition. PMQ, one of the industry trade periodicals, had started its own video platform, but its content was total garbage, he assured me, barely getting a couple hundred views six months after it launched. “Check this one out,” he said, gesturing to his phone. “We got 80,000 hits.”

Opportunity, more than glory, had brought Coniglio to Vegas. Not only would the expo afford plenty of quality “content” (Coniglio had hired two camera guys for precisely this reason), but it was also crawling with representatives from all the big suppliers: Caputo Flour, BelGioioso Cheese, WoodStone Corp, and the California Milk Advisory Board. Sitting in the back seat, Coniglio thrust a pitch deck into my hands, which explained how sponsors might capitalize on his ever-growing celebrity.

Given that Americans consume about 3 billion pizzas every year, it’s hard to believe how quickly the lowly street food of 18th century Naples has become a staple of our culinary lexicon. The first icons of the Great American Pizzeria—places like Lombardi’s in New York City and Frank Pepe’s in nearby New Haven—appeared around the turn of the 20th century. Run by Neapolitan immigrants, the early pizzerias were fast, unpretentious, and cheap. Patrons guzzled beer at a long communal table; pizza was served on large pewter plates. Today there are over 75,000 pizzerias in the United States turning out dozens of regional styles: Chicago deep-dish, Detroit-style, Ohio-style, St. Louis-style. There are mushrooming numbers of schools and certifying bodies devoted to maintaining the authenticity of Neapolitan-, New York-, and Chicago-style pizzas.

Most of America’s 75,000 pizzerias care little for cultural patrimony. The big chains operate upwards of 33,000 restaurants, and what remains is a constellation of neighborhood joints, family restaurants, and local slice shops fighting uphill battles against rising rents, labor costs, interest rates, and competition. While the mom and pops still outnumber the big chains in numbers of locations (although that gap dwindles every year), the latter commands most of the revenues. “Opening a pizzeria is to play roulette with your livelihood,” one panelist mournfully admitted at an afternoon session. “You’re sacrificing the safety of a 40-hour workweek for an 80-hour week lifestyle.”

The International Pizza Expo, entering its 34th year this month, dignifies the pizza maker’s quotidian struggles. For three days each spring, thousands of men—the vast majority of pizzeria operators are men—roam two acres of marinara-red carpets installed on the ground floor of the Las Vegas Convention Center, up and down numbered corridors lined with sauces, cheeses, POS systems, and pizza boxes. They drop in on roundtables on delivery and specialty cheese. They discuss sourcing and costing at the School of Pizzeria Management and watch demos by pizza greats. Men compete in box-folding and dough-stretching contests at The World Pizza Games® for thousand dollar cash prizes.

The Games start on the first day of the expo and reach their climax on the second night with the acrobatic dough tossing finals. They serve complimentary buffalo wings and well liquor. There’s mood lighting and music and shuffleboard. Much of the crowd is tanked by the time the main event begins at 8 p.m.

Coniglio got his start tossing dough competitively; many of the big-name pizza makers did. Tony Gemignani held a Guinness world record for his number of consecutive shoulder-rolls. Putting on a good show is a rite of passage for any earnest pizzaiolo, even if it didn’t necessarily confer culinary credibility. “You don’t need to throw a bottle around like Tom Cruise in Cocktail, but it’s fun for the customers,” Coniglio told me. “Doesn’t mean the pizza tastes any better.”

A couple years ago, Coniglio gave up performance for coaching. He had trained a guy for this year’s event, but the competition was steep. The performer before him was a star in Korea and his act sent the Vegas crowd wild. He appeared on stage in a white Jason mask and twirled a Frisbee-sized disk of dough around his body to the saxophone hook of Flo Rida’s “GDFR,” spinning it faster and faster until the song reached the bridge, at which point he ripped the disk in two balls and slammed them to the ground, sending two white clouds of flour into the air. He tore off the mask and threw it into the crowd. The room erupted in cheers.

Coniglio’s guy, Scott Volpe, was a lanky kid from Tucson wearing baggy khakis and a tee shirt, holding one limp slab of dough in his right hand and tottering a second on the top of his left foot before kicking it into the air and beginning to juggle. “Bring it back to New York!” Coniglio yelled from the side of the stage as Volpe moved into his more difficult b-boy tricks, ending the performance by dropping onto his back and gyrating on the ground while flitting between his legs two slabs of dough, trembling like elastic flying saucers. The whole thing was over in less than three minutes. 282 points. He had killed it.

Coniglio’s crew jostled their man of the hour—covered in flour, gold medal around his neck—out of the convention center, into the parking lot, and through a succession of restaurants, bars, and casinos. It was an auspicious sign before tomorrow’s bake-off, we all agreed, which would happen on Nino’s birthday. There was free pizza and Jameson just about everywhere. Coniglio seemed to know everyone. McCann flirted with the women and laughed at their jokes as he drank himself into oblivion. But the more Coniglio drank, the more elaborate his ambitions became.

“Know what comes next? Know what I really need?” he said. “I gotta have a book. Gemignani’s got a book. Chris Bianco’s got a book. Mario Batali’s got like six of them. I can’t write for shit,” he said, turning to me. “but I’ll make you a deal. You write this book for me, and you’ll be part of the crew. Capiche? 80% of the profits would be yours.” That was Coniglio’s shtick, I soon learned: that he would compensate, that the money would be there soon. “I’m an asshole,” he often said, “but I’m not a dick.”

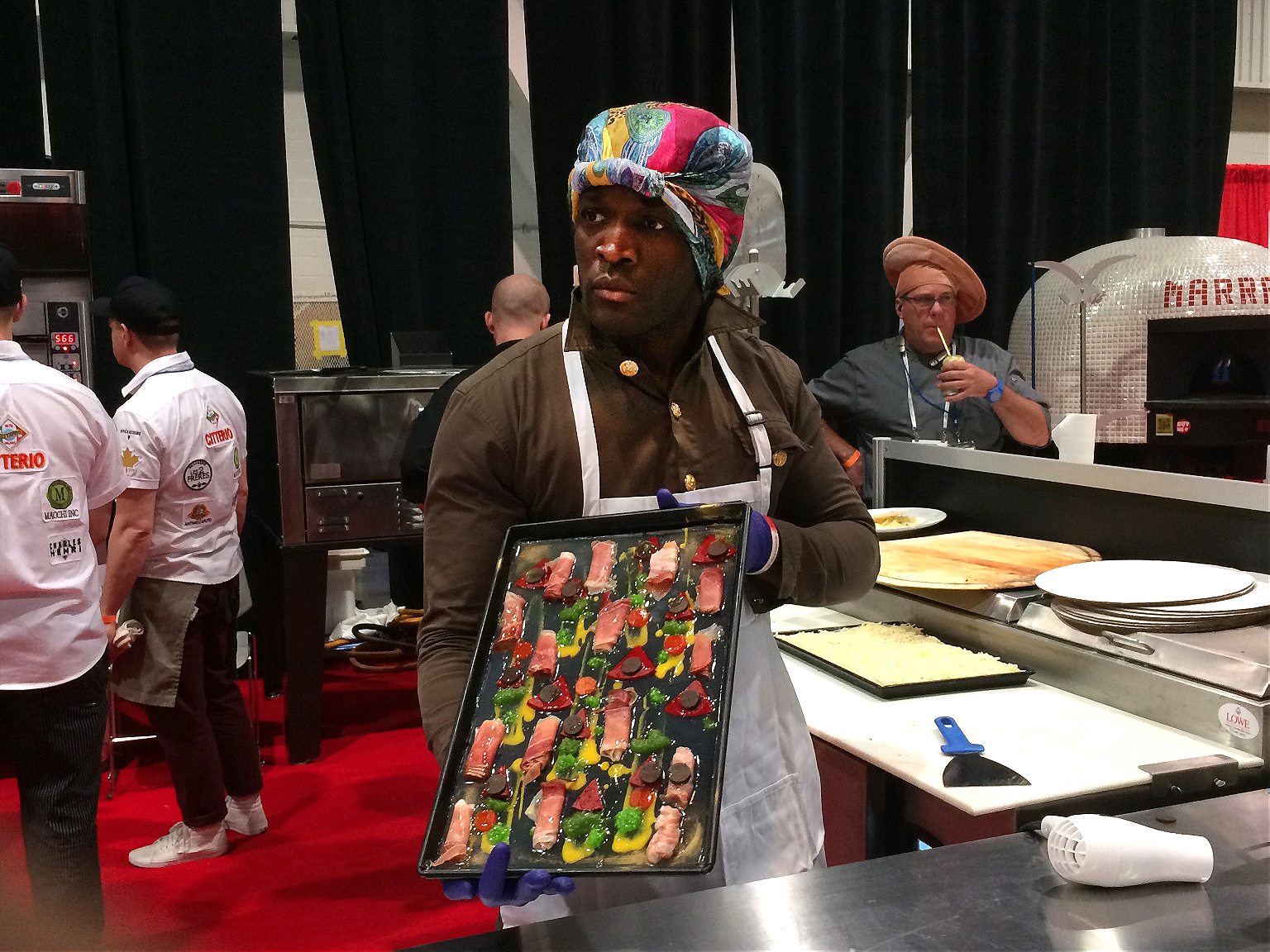

The warm industrial odors emanating from the stain-resistant carpets nearly overpowered me when I walked into the exhibit hall the following day. Rows of uniformed vendors were already putting the last minute touches on their booths, stabbing toothpicks into bite-sized cheese squares, testing the temperatures of their ovens, arranging stacks of informational leaflets into tidy symmetrical shapes. The tall Styroboard arch entranceway to the makeshift championship stadium was already thronged with people. A guy in a Food Network baseball cap positioned his equipment directly in front of a tall glass trophy case, neurotically twisting his lens back and forth to zero in on his money shot.

Coniglio would be going up against Tim Silva of Pizza My Heart, an eight-location slice operation based in the California South Bay. Founded back in 1981, Silva’s place was a local institution. The folksy 60’s surfer vibe has come to feel dated, but Silva was no has-been, having won the baking championship just two years prior.

To his left stood Shawn Randazzo, the boyish Detroiter who had helped put Motor City’s thick and unctuous square pies on the international map. Having started his career as a delivery driver, Shaun had risen through the ranks to a world title in 2012. For the older judges, though, pan-style pies were still a hard sell. Shawn was the perennial underdog.

Beside Randazzo was Graziano Bertuzzo, the Apulian legend whose face was plastered all over the exhibit hall in ads for Italian cheeses and flours. Grayer and slighter than his pictures suggested, Bertuzzo carried his wiry jockey’s frame with youthful pride, shoulder length hair tucked under a white baseball cap.

Each contestant’s pizza would be judged on crust, sauce, cheese, topping, creativity, and overall flavor, with a wildcard thrown in for good measure: contestants also had to use three additional ingredients, revealed, Iron Chef-style, moments before the competition began. This year’s ingredients were blood oranges, pancetta, and Mugolio syrup, a viscous golden liquid made from the tender springtime buds of the Mugo pine, which grow in the Italian Dolomites. Only a handful of people in the world have a license to forage for them.

McCann, his eyes bloodshot and shoulders hunched handed me a Styrofoam plate with a couple dark brown drops, which I licked off of my finger. It had a mild, resinous sweetness. “Maple syrup on acid!” the emcee proclaimed.

There is a strange tempo to these live baking competitions. The contestants set a frenetic pace, working as efficiently as they can to get their finished pizzas to the judges first (speed lends a well-known competitive advantage; the later the judges try your pie, the greater the risk of sensory fatigue and gut bloat). The spectators regale themselves with beer and slices leftover from the previous hour’s competition. I found my attention continuously wandering between watching Coniglio in person, his every movement recorded by a corps of nervous cameramen. He was arranging prosciutto and sausage with such manic focus and precision that I almost forgot about the blackjack tables last night, that he was probably still drunk, and that he probably hadn’t slept more than an hour.

“I’m using four cheeses on bottom,” Coniglio told a hovering reporter. “Mozzarella, Grana Padano, goat cheese, and gorgonzola. And then I picked up this stracchino in the exhibit hall just the other day. Gonna put it on halfway through the bake. Give the pie a little texture.” Coniglio was a strict formalist when it came to his toppings. Charcuterie, zucchini flowers, pine nuts, and walnuts were all fair game. But woe to the “momos,” “hooligans” and “troll-ass motherfuckers” who dared to ask for ranch dressing or pineapple.

“That’s a magnificent looking pie,” the emcee marveled.

“That’s what I try to do, bro. Keeping it real. Keeping it simple.”

On the other side of the stage, Silva was sautéing onions and pancetta with Calabrian chiles, Randazzo was adding dried oregano to a blood orange compote, while Bertuzzo was marinating shrimp and asparagus in olive oil and the Mugolio syrup. Next to him, a female translator busily explained his process, as Bertuzzo didn’t speak a word of English.

Bertuzzo had made the mozzarella himself that morning. He had fermented his dough for 72 hours. He had dedicated his life to the sciences of yeast, leavening, hydration, and digestion: how to treat dough with fruit-soaked water for a natural fermentation, and how to make it lighter and crispier by restarting the dough with ground Arborio rice.

If Bertuzzo was concerned about being the last competitor to finish, his worries were undetectable. His hands trembled slightly as he nudged his peel under the pie and eased it out of the oven, trailed by half a dozen video cameras. This particular pizza, the translator announced, could not be divided with a wheel cutter like the other pies, but instead must be cut with scissors. Slicing would compromise the delicate architecture of the crust, causing it to lose some of its ethereal puffiness.

The judges scrutinized the pizza with furrowed brows, scribbling notes, lifting up the crust to inhale its aromas while inspecting its weight and girth. They chewed with deliberation and purpose, as if trying to slow the fading of treasured childhood recollection.

The day before the competition, a man had asked me if I was familiar with the theory of the “third place.” I’d heard of it: if homes were our “first places” and offices were our “second places,” then our “third places” were all the cheap and habitual public destinations—cafes, clubs, libraries, coffee shops–where regulars gathered. Third places anchored our local democracy. Civil society couldn’t run without them.

“I’ve got another theory,” he said, slurping his wine while a waitress gathered plates of ravaged antipasti. “The pizzeria is our ‘fourth place.’” I must have looked unconvinced. I struggled to read his badge. He was a restaurant consultant of some kind. “Hear me out,” he cried, feverishly pouring himself another glass of wine. “It’s not like when you decide to go out for pizza, you go anywhere. You already have a spot in mind, eh? You go to your pizzeria.”

Given the growing influence of the big chains, with their mastery of technology, their bottomless advertising pockets, and their ever-growing market-share, the “fourth place” theory sounded, at best, like a fantasy. But that’s not the impression you get watching the four pizzaioli compete. Inside the makeshift championship stadium, enclosed in a temple of Styroboard, all of the myths we ascribe to the dish—the tradition, the craft, the proud brotherhood of self-made pizza-men—felt very much alive.

The fantasy was not to last. After much deliberation, the judges announced their winner: Coniglio had come in second. Bertuzzo had won. The expo was over.

Bertuzzo or no, Coniglio and the Brooklyn Pizza Crew had filmed over forty hours of footage, enough for a full-length documentary. And there was still much more to come: meetings with executives at Stanislaus Food Products and the CEO of BelGioioso cheese, the Pizza and Pasta Northeast in Atlantic City (where Coniglio would compete in the third annual Caputo Cup), the Longest Pizza in the World competition to be held in Fontana, California. New pizzerias would open, with new managements and menus and opportunities to consult.

We passed the ruins of boxes and signs and demonstration copies of gleaming metal machines en route to the casino bar. The cleanup crew was already starting to tear out the bright red carpets, exposing the concrete underneath. On the way out, Coniglio kicked over an elaborate gazebo made of pizza boxes. One of his camera guys caught them on film toppling chaotically to the ground. Coniglio smirked at the camera as he pounded and crushed them into the floor. It was his birthday, after all.