A plan to honor warrior-king Shivaji Maharaj with a giant statue in Mumbai threatens the fishing communities that were the city’s first inhabitants.

On a warm December night in 2016, Damodar Tandel and 150 fishermen were arrested in Badhwar Park in the heart of Mumbai, India’s largest city, because of a giant bronze statue that hadn’t been built yet.

Tandel, the head of the powerful state fishermen’s association, the Akhil Maharashtra Machhimar Kruti Samiti, had been planning a series of high-profile protests against the construction of what is intended to be the world’s largest statue, a 695-foot (212 meters) likeness of the 17th-century warrior-king Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. The statue is planned to be built in the center of a 40-acre artificial island in the middle of the city’s harbor, complete with a museum, helipad, and an amphitheater.

When completed, the statue of Shivaji will be twice the size of the Statue of Liberty and will dethrone China’s Spring Temple Buddha as the tallest in the world. According to the project’s contractors, the first phase will cost at least $400 million. Once completed, it is expected to draw 10,000 tourists per day. But even before construction has begun, the statue has exposed the deep fault lines between the city’s many ethnic and cultural communities, schisms that radiate out across South Asia.

The fishermen’s plans never materialized that day in December. As the group’s press conference, led by Tadel, drew to a close, a swarm of police rushed in among the flashing cameras.

With the movement’s leadership out of the way, the celebrations to launch the statue project went as planned. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, leader of India’s right-wing ruling party and purveyor of the Hindu Nationalist political agenda, rode an Indian Coast Guard hovercraft a short distance from the Mumbai shoreline. Near an inconspicuous patch of gravel that only surfaces during low tide, he tipped a vessel of water and a handful of soil overboard in a ritual known as “Jal Pujan,” entreating the deities to bless the location of the future statue.

[Why the fishermen from two countries are locked in a deadly battle]

Nearly 18 months after his arrest, I met Tandel in his home in the Cuffe Parade fishing village: a cluster of narrow lanes, squat concrete buildings, and thatched huts wedged between expensive high-rises and the sea. The village sits on a finger of land near the southern tip of the funnel-shaped city, adjacent to some of the highest valued real-estate in South Asia. Serious and visibly frustrated in glasses, a salmon-colored shirt, and khaki shorts, Tandel leaned forward as he told me about his community’s concerns. “We oppose the place where the statue is being built, not the statue itself.”

He handed me two plastic binders filled with reasons why. Inside were sheaves of photographs of crustaceans and healthy corals, the precious breeding ground for fish, lobster, and crab, all right at the location where the statue will someday rise. “This is the golden spot for fishing.” Without it, he said, “fishing will be done in Mumbai.”

[A journey into the world’s largest mangrove forests]

According to census data from the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, in 2010 there were more than 386,000 “fisherfolk” in Maharashtra—India’s second largest state with a population of 112 million—most of them from a community known as the Kolis. The number of people earning their livelihoods on fishing boats has almost certainly increased in the last eight years due to the growth of the deep-sea fishing industry in the Arabian Sea, but the fishermen most affected by the statue work on a smaller scale. These fishermen go to sea daily in five-to-six foot-long, non-mechanized fishing vessels, set their nets in the relatively shallow waters near the coastline for hours at a time, and row back each evening, the hulls of their boats laden with fish, crab, and lobster. Their catch does not make them rich, but it does provide a steady source of income.

Nearly 41,000 people in Greater Mumbai are connected to the fishing industry. Most of them live in the thirty or so Koli fishing villages that were among the first settlements built on this land when the place that is today’s Mumbai was a marshy archipelago of seven small islands. The modern city of Mumbai originated as a small fort built on one of those islands in the late 16th century by the Portuguese, who named their settlement Bom Bahía, or good bay. In 1661, the island fort was handed over to the British who anglicized its name to Bombay. In order to attract trade from the Mughal-controlled port of Surat to the north, the British created tax incentives to draw merchants, laborers, and professionals from across the Subcontinent to their fledgling trading post. In the coming centuries, the marshes were filled and the city expanded, engulfing the Koli villages as it transformed into India’s richest, most cosmopolitan urban center.

Their catch does not make them rich, but it does provide a steady source of income.

Growth, however, was insufficient to bridge the city’s deep linguistic, cultural, and ethnic fissures. Following independence from the British in 1947, a fierce debate emerged about how best to divide India’s complex terrain, with its hundreds of dialects and multiplicity of faiths. One solution was to organize states around language. Marathi speakers would be politically unified in the state of Maharashtra, which stretched from the Arabian Sea coast deep into the rural heartland. By the mid-1950s, this left one looming question: what would happen to polyglot Bombay?

In 1960, after years of protests and complex negotiations, the city formally became the capital of Maharashtra. Not long after, a political cartoonist by the name of Bal Thackeray saw a way to capitalize on the growing tensions among its ethnolinguistic groups. Thackeray launched a publication called Marmik, in which he lampooned various migrant groups—especially South Indians who, he said, came to Mumbai to steal jobs from Marathi-speaking “sons of the soil”—in order to fan the flames of populism. By 1966, he created the political party Shiv Sena, translated literally as “Shivaji’s Army,” as a voice for the supposedly disenfranchised Marathas.

His followers frequently targeted and attacked South Indians and their property, gaining Shiv Sena a reputation for extremism and violence. In recent years, the Shiv Sena has redirected its ire north, toward Hindi-speaking migrants from the region sometimes pejoratively referred to as the “cow belt.”

Perhaps nothing did more to cement the Sena’s violent reputation than the notorious Bombay riots of the early 1990s, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 900 Mumbaikars, a majority of them Muslim.

In 1995, less than three years after a government investigation found the Shiv Sena had “whipped up a communal frenzy,” Thackery’s party won power in the state government and promptly renamed the city. Bombay became Mumbai, a name derived from the Koli fishing community’s patron deity, Mumbadevi. While many residents now use the two names interchangeably, the name “Mumbai” has always represented an effort to privilege Maratha identity in city politics.

For the last thirty years, in statewide elections, the Shiv Sena has joined in a sometimes tense alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the right-wing party that swept to national power in 2014 with the election of Narendra Modi. Since then, Shiv Sena has been the BJP’s junior partner in the Maharashtrian government. The statue, as Modi’s presence that day in December makes clear, is a pet project of the BJP government.

Despite that, Tandel says, the Sena is very much against it. The BJP, he guarantees, will lose the votes of the Maharashtrian fishing community if it moves forward with the statue’s construction. Plans for the statue continue to unfold.

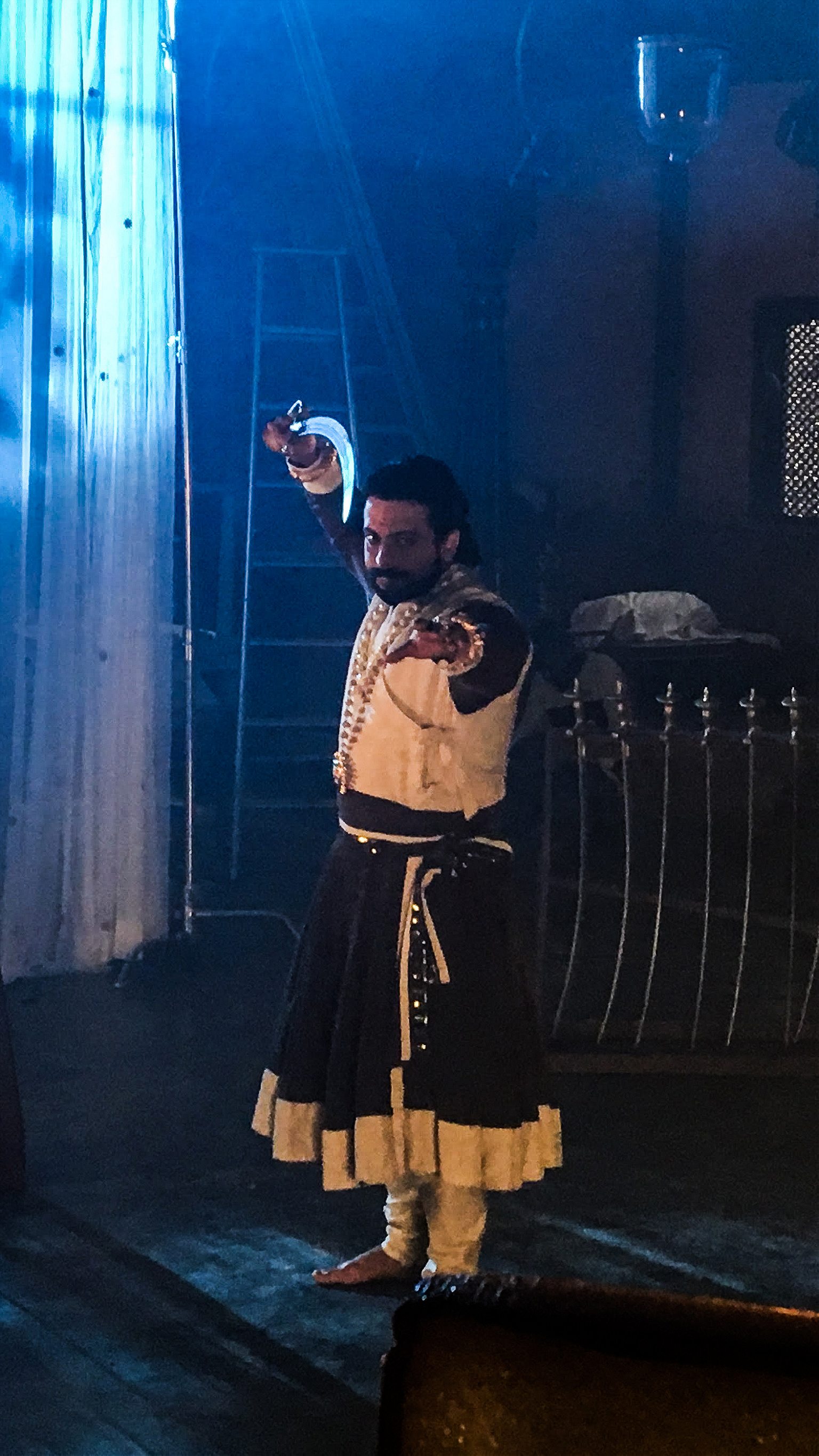

On a brutally hot day in April, inside Mumbai’s Film City studio complex, the beloved Maharashtrian actor Amol Kolhe clutches a curved prop sword overhead, glaring menacingly at the camera. For years, Kolhe was the celebrated face of Shivaji Maharaj—the founder of the Maratha Empire and the most iconic figure in Maharashtrian history—having played him on both Hindi and Marathi television serials. These days, Kolhe has taken on the role of Shivaji’s son, Sambhaji, and serves as a spokesperson and deputy leader for the Sena. As an actor, Kohle brings the era of Shivaji Maharaj to life for millions of Indians sitting around their television sets; as a politician, he furthers what he sees as Shivaji’s vision under the banner of “Shivaji’s Army.”

“There are some issues over which a stringent stand has to be taken,” he says, “but Shiv Sena always keeps the local people’s interests in mind. Many times it is said that Shiv Sena is a radical party, but that’s not accurate.”

On the subject of the statue, Kolhe is unequivocal. The Shiv Sena, he says, supports the project as a means for drawing international attention to the story of Shivaji Maharaj. In Mumbai itself, Shivaji already lends his name to an affluent neighborhood and the large park at its center, the international airport, and Asia’s busiest railway station; internationally, he is an obscure historical figure, at best.

From Mumbai, I travel several hours east to the city of Pune, the second-largest urban center in Maharashtra, to meet Rahul Chemburkar, a Mumbai-based conservation architect. He leads me into an elaborate replica of a 17th-century fort complex called Shivrushti, a sprawling, interactive echo of Kohle’s set in Film City. Once completed, Chemburkar imagines this “historical theme park” as a fitting tribute to an equitable and generous ruler. Though a devoted Hindu, Shivaji Maharaj oversaw a kingdom that was notable, by the standards of the day, for its tolerance and respect for difference. Like the Mughal emperor Akbar, who ruled out of Delhi and Agra a century earlier, Shivaji allowed for different religions to flourish in his kingdom. In a land fractured by countless divisions, he enshrined a form of patriotism rooted in pluralism. “Shivaji is in the DNA of Maharashtra,” Chemburkar says, “and in the DNA of India.”

For Chemburkar, who descends from a community of shipbuilders and artisans known as Paachkalshi, and can trace his community’s roots in Mumbai back to the 13th century, the work of architectural restoration is also the work of creating an identity. “We [should] ask ourselves if [the statue is] going to help the society to identify itself. Art gives you a reason to celebrate your life, or your life is just bread and butter,” he says, “but art is not needed when it becomes a liability.”

In Chemburkar’s view, the plan for the statue is both aesthetically lacking, and a poor means of promoting Shivaji’s legacy, diverting public funds from more valuable projects like restoring the hundreds of crumbling fortresses that he built across the state. Projects like the statue, he told me, treading very carefully on diplomatically fraught terrain, must draw attention to Shivaji’s character and accomplishments, rather than foment political divisions. “The petty use of Shivaji name is what pains the common people,” Chemburkar said. “Our political leaders need to go the extra mile now to overcome the rift that has formed between us and them.”

But the political debate around the meaning of Shivaji shows no signs of abating. The BJP, the current ruling party, has continued to advance the Shivaji statue as part of their political program in Maharashtra. Asked about criticisms of the Shivaji statue, a BJP spokesperson said that the local economy would benefit from the tourism, and promised that the fishing communities affected would be accommodated in tourism and development. The spokesperson did not go into details.

On the same day that Damodar Tandel went to jail in December 2016, firebrand politician Sanjay Nirupam says he was placed under house arrest for attempting to stage a silent protest in the vicinity of a public event led by Modi. Local officials denied that accusation, stating that much of the city experienced similar lockdowns due to the Prime Minister’s visit. Nirupam had planned to use Modi’s arrival in Mumbai to demonstrate against the government’s controversial economic program known as demonetization, which abruptly removed 86% of the Indian currency from circulation in 2016, ostensibly in an effort to curb corruption and terrorism.

A verbose, larger-than-life figure, Nirupam is the chief of the Mumbai branch of the Indian National Congress, the party—now in opposition—that had dominated India’s political scene since its independence until the election of Narendra Modi. Though it was the Congress Party that first developed the idea of the statue in 2004, Nirupam has a clear idea of who to blame for the current problems: “For the BJP, [the project] is not a matter of commitment or dedication, it is just an election issue,” he says, a showy tool to drum up BJP votes from the Maratha population.

Nirupam was a member of Shiv Sena until a bitter dispute with party leadership led him to resign in 2005. He says the money for the statue—a staggering budget by Indian standards—could be put to better use helping the farmers of Maharashtra, whose economic hardships have led to a years-long spate of suicides, including nearly 700 in the first three months of 2018 alone. As we speak, he rattles off a list of regional economic trends: the textile market, down; exports, down; GDP growth, “only on paper.”

While the Indian economy is growing slightly faster than expected, a number of major industries are suffering and unemployment is on the rise. “Now,” Nirupam says, “is high time—the perfect time—to reconsider [the statue].” Though controversies swirl around the project’s construction, and media coverage has been mixed at best, it’s hard to know just how popular the statue really is. In February 2015, the state government passed an amendment retroactively declaring that public hearings would no longer be necessary for projects deemed to be in the public interest – projects like the Shivaji statue.

In the meantime, Nirupam says, the Congress “cannot afford to go against Shivaji Maharaj.”

This has left common citizens like Tandel, who is also challenging the project in court, to take up the mantle of that opposition. In December 2016, writer and long-time Mumbai resident Karishma Upadhyay created a change.org petition that called on the government to spend the hundreds of millions of dollars designated for the statue on “education, infrastructure, food…anything but a statue that is of no use to anyone.” Shortly after, she started receiving death threats and demands that she “go back home” to her native state of Bihar in the north.

Despite the violence of that response, and the seeming inevitability of the statue’s construction, members of the fishing community continue to fight for their land. Ujwala Patil leads the Koliwada Gaothan Vistar Kruti Samiti, an association of hundreds of Koli women who run Mumbai’s bustling fish markets, and is a representative to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

For Patil, the fight over the statue is just one part of a larger struggle against the destruction of her community’s culture. Most Koli land stands on prime seafront real estate where developers and politicians build pet projects and high-rise apartment buildings. The government is currently moving forward with its plan for a twenty-mile expressway that would follow Mumbai’s western shoreline, connecting the wealthy northwestern suburbs to business districts in the south and cutting off access to the sea for Koli villages along the way.

Patil worries that a massive elevated platform in the Arabian Sea could disrupt the delicate tidal patterns essential for the survival of marine life, patterns that have already begun to shift due to the effects of climate change. I had joined Patil at a leadership gathering of a community of fishermen and fisherwomen in Mumbai. Patil spoke to the assembled leadership about the complex array of problems facing the community. “We don’t belong to the city, even though we live here. We are urban villagers,” Patil said at the meeting that day.

The plans for the statue pose not just a threat to the Koli livelihood, but also an existential threat to their sacrosanct independence from the crushing pressure of the city itself. “The rules that are made will be made in the villages,” she went on, “and the villagers will make them.”