The Boqueria has stood strong through civil war and political divisions, tyranny and terrorism, economic crises and natural disasters, but in recent years, it has encountered a new relentless challenge: mass tourism.

Maria Teresa de Pablo has been buying her food from the Boqueria for 68 years, since the days she came here with her parents and learned the ways of the market—the language, the etiquette, the stands that earned her family’s loyalty. She lives on Carrer de Petritxol in the heart of the Gothic Quarter of Barcelona, a few blocks from La Rambla. She likes to start her shopping early. By 8:15 am, she steps out from her building onto the narrow back street, referred to locally as Chocolate Street for the number of churro-and-chocolate shops packed into its 200 meters. She pushes her empty green cart through the narrow stone passageway, still ripe with last night’s revelry, turns left on Portaferrissa, then crosses over the smooth stone tiles of La Rambla, past the iconic flower shops still shaking off the slumber, and through the side entrance of Barcelona’s largest and most famous market.

Maria has maintained this routine for nearly seven decades, through lean years after the Spanish Civil War, during the long, tense years of Franco’s dictatorship, through the ‘90s when Barcelona emerged onto the international stage, and into the 21st century as Barcelona grew into one of the world’s favorite destinations. Through all the years and all the changes, Maria has continued to do her shopping—buying her jamón and dried sausages from Cansaladeria Ayala, her beef and milk-fed lamb from Carnes Serrano, her purple onions and leeks and baby peas from the farmers who set up on the western edge of the market. At every stop, she chats with the families she’s known for generations—about the weather, about Catalan independence, about the changes across Barcelona. “I used to buy from their grandparents, then their parents, now them. Always the same shops, always the same routine.”

But in recent years, it’s become harder for Maria to maintain the routine—not because of her age, at 82 years old she is full of life—but because of the makeup of the market. “The hordes of people pouring into this market make it hard to walk. I’ve had to change the route I take through the market just to get my shopping done.”

She doesn’t plan to give up—she’s been doing this too long to turn back now—but she doesn’t see a bright future for the market that has sustained her and her family for generations. “It’s not the same market anymore. Look around, the old places are all starting to close.”

The Boqueria has stood strong through civil war and political divisions, tyranny and terrorism, economic crises and natural disasters, but in recent years, it has encountered a new, relentless challenge, one that threatens to undermine the essence of one of the world’s greatest markets: mass tourism.

El Mercat de San Josep de La Boqueria has lived many lives. In the early 13th century vendors set up stands in the open air a few paces from the Mediterranean, just outside the stone wall that circumscribed the old city. The Boqueria was strategically situated on the path to the Llobregat river on an old Moorish trading route, a perfect post for the perambulating purveyors of the day. Back then it was largely a meat market; the name itself derives from the Catalan word for goat, boc, the protein of choice for the savvy medieval shopper.

The beta Boqueria went on like that for centuries, an ever-rotating selection of farmers, fishermen, and butchers selling whatever they had on hand, until the early 1800s, when Barcelona’s principle market moved a few hundred meters up the Rambla. The central part of the Rambla back then was a dense concentration of convents, monasteries, and other religious buildings, and at first the vendors set up in whatever open space they could find. In 1836, during the Carlist Wars that upended the religious establishment, the Convent of Saint Joseph was burned down and demolished, making space for the Boqueria to take up home where it still resides today.

First, vendors gathered spontaneously and sold their product on blankets spread across the ground, or directly from the wooden carts they used to transport their goods, then on tables erected each morning and dismantled by the afternoon to leave the area free for strolling. By the end of the 19th century, a roadmap for today’s market began to emerge—more than 300 stands in total, organized by the products they sell: fresh and cured meat; fresh and salted fish; and fresh fruits and vegetables. Gas lighting arrived in 1871, a day before Christmas.

The organized market made quite the impression on visitors: “It is a magnificent place, frequented by an immense crowd of sellers and buyers, with the look of a grand city,” wrote German professor Hermann Alexander Pagenstecher in his diary. “Hundreds of different stalls can be found in it arranged to the variety of the goods, which offered a multicolored exposition for all tastes and pockets.” Wide-eyed and full of zeal for this extraordinary confluence of food purveyors, the professor “bought an extraordinary anchovy to study it.”

But political turbulence and bureaucratic torpor kept the physical market from finding its final form. In 1913, after decades of half measures, city officials completed construction of the cast-iron roof over the plaza, establishing the perimeter for the Boqueria that still stands today. The famous arched entrance paneled with stain glass, created by modernist architect Antoni de Falguera, came shortly after.

The Boqueria has all the ingredients of a world-class market: the size, 30,000 square feet of floor space where more than 250 vendors sell their goods; the variety, a mix of local and exotic products offered by a diverse network of local farmers and broad-minded merchants who introduce to the city’s cooks the flavors of the world at large; and the specialization, where three or four generations of family history means that vendors carry with them the collective knowledge of their ancestors, experts of micro-culinary disciplines: shellfish from the Galician coast, wild mushrooms from the Catalan forests, butchers of viscera and odd bits.

This is the market that has fed Barcelona for 800 years, while Columbus sailed the ocean blue, during the Inquisition, the Spanish Civil War, the decades of Franco. This is the market that helped shape Catalan cuisine into one of the most delicious and sophisticated regional cuisines in Europe. And this is the market that helped fuel the modernist food revolution of the early 2000s, the one that made Spain the hottest food destination in the world, a movement largely defined by avant-garde technique but that was always driven by a rigorous dedication to product and seasonality.

I’ve lived many lives of my own in the hallowed grounds of this market. I first stumbled onto it by chance back in 1999 on a trip to Spain with my high school Spanish class. Wide-eyed and thirsty on our first afternoon in Spain, a group of friends and I set off on a scavenger hunt through the old part of the city, in desperate search of a bottle of absinthe after reading an article about its magical properties on the plane ride over. The green fairy and her payload of mind-altering wormwood eluded us for the first few hours, until we came bounding down the Rambla and through the gates of the Boqueria. I had never been to a true market before, barely knew that they existed, so the sights and smells of an open food emporium were like a drug for my innocent American sensibilities: dangling legs of jamón; schools of whole fish, their smooth silver bellies nestled into beds of ice; piles of vegetables still crusted with the Catalan countryside. No plastic wrap, no halogen bulbs or air-conditioned aisles; food out in the open, for the taking, there to be touched and tasted and talked about. That we found the absinthe in a wine store on the edge of the market only further emblazoned its shape on my brain.

The produce and protein [are] so vivid and transfixing they infer themselves into your meal plans.

Three years later, those early memories drove me back to Barcelona to study abroad. I asked to be placed with a family that would allow me to do my own cooking, and in the afternoons, after class let out at the University of Barcelona, I’d ride my skateboard through the Raval into the backside of the market, where I’d stuff my backpack with as much produce as I could get for the change in my pocket. The Boqueria became my true classroom—a place to practice my Spanish, absorb a few castellano and Catalan colloquialisms, water the seedlings of a few unexpected friendships. For a young traveler in a new world, few feelings can compare to being recognized as a regular in a foreign institution, and when a handful of vendors began to address me by name (or as “el californiano”), I was ready to cancel my flight home at the end of the semester. When asked to give a presentation in Spanish on an important aspect of Barcelona culture for a final in my conversation class, I spent 30 minutes mapping out the market for my classmates, dispensing tips on where to find the cheapest, plumpest avocados and who sliced the finest jamón by hand.

I like to say that I learned to cook in the Boqueria—partly because it sounds cool, but mostly because it’s as true as the sky is blue. I arrived in Spain as a kitchen novice with a growing passion for food but without a clue how to handle fresh ingredients. The true beauty of a great market is that it compels you to cook, the produce and protein so vivid and transfixing they infer themselves into your meal plans. Through sheer osmosis you find your universe expanding. I learned what animals looked like in their post-mortem, pre-butchered state. I learned that there is a whole world of fungus beyond buttons and portabellas. I learned that there are more fish in the sea than salmon and tuna.

And where better to learn about cooking new ingredients than from the people who handle them every day? Llorenç Petràs, the grumpy fungus king of Catalunya, who begrudgingly gave me tips on which mushrooms needed dry, high heat and which required low, slow, moist cooking. Or the old woman who ran a dried goods stand who taught me how to pound almonds and parsley in a mortar and pestle into a thick picada for thickening stews. Or the cleaver-wielding women of the fish market, who implored me to try cooking smaller, cheaper, fattier fish. So deep were the lessons that before returning to the states at the end of the semester, I extended my stay and enrolled in summer classes at a culinary school in the Basque Country.

By the time I came back to Barcelona in 2010—this time for keeps—I had cooked in half a dozen restaurants, long and hard enough to know that I didn’t want to be a chef, but that I wanted a life in food. The Boqueria was my first stop. I finally had enough money to do what I had never done before—to eat in the market—so I took up a stool at El Quim de la Boqueria and ordered the kind of breakfast that you cross oceans for: fried eggs and baby squid, sautéed wild mushrooms with a streak of sweet sherry, a bottle of Catalan bubbles. While a late-summer storm soaked the city, I sat on my stool, sated, slightly buzzed, a stupid little grin stained on my face. Happy.

I stayed in Barcelona for a woman, now my wife, but I also stayed for the Boqueria. Any society capable of creating a market as potent and poetic as this is a place I wanted to be a part of.

It was the reason that all six places I lived in during my first turbulent year in the city were within a few blocks of the market. And it’s one of the principle reasons I still live in the center of the city, a ten-minute stroll from its baroque metal entrance.

But the market, like the city itself, had changed in the eight years since I’d been back. More foreign faces, fewer Catalans. More sunburns and flip flops, fewer old women and pushcarts. The first signs of takeaway food—pre-sliced jamón and cheese, sandwiches—had begun to surface in small pockets across the market. The vendors seemed less jovial, less patient. The first “Photos No!” signs stared back at you from behind the glass of the market stalls.

These were just the early signs of a radical transformation that has taken shape over the past ten years, one that has essentially split the Boqueria into two markets: one for the locals, mostly older clients like Sra. de Pablo who are too far down the road to turn back now, and one for the tourists, who look to fire off a few photos, deposit a few euros into the palms of anyone offering some quick calories, and move on. Guess which side of the market is winning out?

Related Reads

Today, I know of only a few people—mostly chefs—who still shop in the Boqueria. For everyone else, it’s too much trouble. Too many elbows and selfie sticks. “Do people still shop there?” is one of the most common responses I get from locals when I tell them where I buy my food.

Instead, they shop at the neighborhood markets removed from the city center, and, increasingly, the bigger supermarkets that have sprouted up everywhere, threatening the time-tested Spanish tradition of buying your cheese from the cheese store, your meat from the butcher, your bread from the baker.

But I’m stubborn. I still shop at the Boqueria three times a week. Most of the calories I consume in Spain come from its purveyors. Over the years I’ve learned how to work the market, how to crack its bones like a chiropractor to get just a little bit more out of it. I know that the porchetta at Aroma Ibèric arrives at 11 a.m. on Thursday, still hot from the wood-burning oven. I know that the ladies at Avinova can find me a 14-lb wild turkey with two days’ notice in late November (even if it means plucking a few straggling feathers before roasting). I know that arriving after 10 a.m. on any day is a recipe for pain and frustration.

To give up on the Boqueria is to give up on Barcelona itself.

I do it because even with one hand bound behind its back, the Boqueria is still the greatest market I’ve ever shopped in, a place where the acorn-fed pork is so marbled it looks like a snowstorm, where teardrop green peas taste like caviar, where baby artichokes and giant red shrimp from just up the road nestle up next to Piedmont truffles and Japanese beef.

But I don’t go there for the quality alone. I go there for the swirling energy, for the sensorial buffet, for the people still doing what they’ve always done, despite the rapidly changing world around them. There’s something in me that feels bound to this market, its life force inextricably tied to the old city and my tiny slice of it.

I do it for the same reason that I still live in the Gothic Quarter, in the eye of the tourism thunderstorm: because this is where the beauty of Barcelona reaches its greatest expression, the city at its most concentrated and captivating. Where the streets are tiny, the buildings are works of art, the history so dense it takes encyclopedias to unpack. And where market life is maddening and majestic in equal measures.

I do it because to give up on the Boqueria is to give up on Barcelona itself.

Josep Maria Sendra wasn’t born into the Boqueria. He grew up dedicated to a different market, to San Antoni a mile to the north of the Boqueria, just on the outer edge of Ciutat Vella, where his father began selling charcuterie in the 1960s. One of five kids, he and his siblings worked at the stall growing up, but one by one the others moved on until only Josep was left to carry on the family business.

After inheriting the business, Josep Maria decided to realize a long-standing dream: to relocate the stand to the Boqueria. “I came here for one simple reason: because I fell in love with the Boqueria. I loved the energy of the market, the incredible vendors working everywhere. I told myself, ‘I want to sell my jamón here.’” In 2002, he opened Aroma Ibéric on the western edge of the market, in stall 183. He worked in a small space, but he prided himself in selling the best cured pork and cheese in the market, and he was rewarded with a steady, loyal local clientele.

Back then, people still came from all over Barcelona and the outskirts of the city to shop at the Boqueria. “From the humblest family to Ferran Adrià, everyone came to the Boqueria.” Given the size and scope of the market, the Boqueria was a shopping destination worthy of a journey. From Sarrià and Gracia and Matarò they came—by car and subway, bus and bike. They came for the deals, in abundance back then when competition was thick between purveyors, and for the quality, unrivaled anywhere in the city, but they also came for the sheer variety of products on sale. If you wanted jalapeños from Mexico or lychee from Thailand or the same red shrimp served in El Bulli, there was only one place to get it. “It was a given fact,” says Josep Maria, “if it wasn’t available at the Boqueria, it didn’t exist.”

Josep Maria did a brisk business at the Boqueria, so when the stall adjacent to his became available, he took over the lease, effectively doubling the size of his operation, adding a robust selection of Spain’s finest cheeses to the cornucopia of cured pork. Business continued apace, but starting in 2010, the makeup of the stalls around him began to shift as tourism became the principal driver of foot traffic through the market. “When I started 16 years ago, it was 80 percent locals shopping at the market. Today, at best, it’s 50-50.”

When I started 16 years ago, it was 80 percent locals shopping at the market. Today, at best, it’s 50-50.

It didn’t take a weatherman to know which way the wind was blowing in the Boqueria. Many of the older vendors sold their licenses and slipped into retirement; others began to transform their stands, trading raw products for takeaway food. Suddenly, Josep Maria found his little corner of the market dominated by smoothie dispensaries, falafel stands, crêpe counters. A decade and a half after moving to the Boqueria, he no longer recognizes the Boqueria he once fell in love with.

Along the way, Josep Maria has made a few gentle concessions to shifting clientele, offering a larger selection of vacuum-sealed jamón and queso, including variety packs offering a greatest hits of Iberia. But you won’t find jamón in a cup or chorizo on a stick or any other newfangled meat creation.

“It’s a charade out there. They’ll put ‘Traditional Product of Catalunya’ on packages of dried sausages with herbs, things we’ve never eaten here. Tourism shouldn’t change how we make our traditional foods.”

If only the madness stopped at herb-crusted fuet. At Boket, the largest seller of red meat in the Boqueria, a good portion of the stand is dedicated to selling mini burgers, beef empanadas, burritos—whatever beef byproducts they can cook up. Two stands over, Puerto Latino offers what must be the Boqueria’s most outrageous selection of takeaway food: chicken nuggets, calzones, ribs slathered with barbecue sauce. Like many of the vendors today, the owners operate a prep kitchen just on the outskirts of the Boqueria, and every few weeks, a new Frankenfood joins the high-calorie roster behind the glass casing—hot dogs coated in an armor of crushed potato chips, say, or falafel cones stuffed with French fries. Tourists crowd around the bright stand—adorned with phrases like “Organic Orgasmic”—and shell out euros for trays of nachos and cups of guac and bottles of cold beer.

Meanwhile, Josep Maria keeps slicing his jamón by hand. He understands his fellow vendors need to make a living, but believes firmly that there are ways of adapting to the territory without ceding entirely to the narrow demands of the cruise-ship set. Above all, he believes the degradation of the market could be avoided with more foresight and enforcement by the local government.

“In Spain, we have a problem of not learning from our mistakes. Look at what happened in the 1980s when mass tourism destroyed the coast of Valencia. We haven’t changed. Now the same thing is happening in Barcelona.” Like so many Catalans, Josep Maria had high hopes when Ada Colau was elected mayor in 2015, riding into office on a platform based largely on the idea of curbing the negative impact mass tourism had wrought on this community. But after three years waiting for some meaningful change, he says he’s given up on the Colau administration. “I hoped things would change, but I’ve been very disappointed.”

For Josep Maria, the Boqueria is more than just another market. “It’s a reflection of the city itself,” he says as he runs his thin blade along the bone of a black-footed jamón leg. “The public space has been sold to the outside world. We’re losing the most important parts of the city.” He believes a few simple proposals could help bring balance back to the market. “Why not make a regulation that states only 30 or 40 percent of a stand’s business can come from takeaway? It would have been a simple measure to implement but they haven’t done it. They haven’t done anything.”

When I mention a rule implemented in 2015 banning tour groups of more than 15 people on the weekends, he laughs. “How do you regulate a market with no doors? Eight come in one side. Seven come in the other.”

If the Boqueria is going to stem the tide of tourism that threatens to undermine its very essence, it would take a force of like-minded vendors to organize and exert pressure—not to radically restrict vendors from making a living, but to keep the beer-swilling, pizza-eating tourists at bay. This is Spain, after all, a country with a deep belief in the power of the collective, where protest is a national sport. For a few years, Josep Maria saw this as the only viable solution to the mounting problem, but his tone has changed to one of resolution, if not defeat.

“There’s too many of them and too few of us. Everyday we’re less.”

The popular narrative is that Barcelona’s ascendance into the upper echelons of global tourism began in the wake of the 1992 Summer Olympics, a rousing cocktail of sports and sun and smooth Mediterranean vibes that introduced the city to a billion viewers. But Barcelona’s true path towards international fame began on November 20, 1975, the day that Generalissimo Francisco Franco succumbed to congestive heart failure.

For the better part of the 20th century, Catalunya had endured a long sequence of tragedy: sectarian violence, civil war, anarchy, poverty, fascism. During 36 years of dictatorship, the region saw its autonomy and regional identity snuffed out under the boot of Franco and his stifling enforcement of Castilian culture. When he finally died and Spain emerged as a democratic nation, the Catalans rejoiced. They embraced post-Franco life with the vigor of a grounded teenager finally released from his bedroom. And what better place to celebrate?

Barcelona is an equal-opportunity destination, as attractive to a pack of Brits on a stag party as it is to a busload of elderly Japanese on a Gaudí bender.

What’s not to love about Barcelona: the wandering stone streets of the Ciutat Vella, where around every corner awaits another hidden surprise—a street lamp designed by Gaudí, a mosaic by Mirò, a tiny plaza with a massive history; the hexagonal blocks of the Eixample, peppered with modernist apartment buildings and a cluster of Michelin stars; a city circumscribed by green, rolling mountains and soft, golden sands and the blue-green breadth of the Mediterranean, with the unflinching weather to enjoy it all year-round? It’s an equal-opportunity destination, as attractive to a pack of Brits on a stag party as it is to a busload of elderly Japanese on a Gaudí bender.

Of course the secret got out (and yes, the Olympics helped spread the word) and of course the people came—in trains and planes and mega cruise ships. They came in such massive waves that in 2017, Barcelona became the third most-visited city in Europe.

Have you been to Barcelona lately? Have you felt the full force of its popularity pumping through its narrow backstreets? Have you stood in line at the Sagrada Familia at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday? Sought out a slice of sand in Barceloneta on a Sunday afternoon in July? Walked the Rambla at any hour, any day, anytime of year? If so, you’ve felt the impact of precipitous popularity on a city the size of Barcelona—with just 6 percent of the landmass of London, and less than half the population of Berlin.

The tourism boom brought billions of dollars into the local economy, but it also set into motion a dramatic transformation of the city center: hotels and hostels, juice bars and bike rental shops, marijuana clubs and mojito dispensaries, all pushing out the services that would sustain a community of locals instead of wave after wave of one-time clients. When a 50-year-old ordinance protecting the Ciutat Vella’s most historic business finally expired in 2014, rents jumped precipitously overnight—from 2,000 euros to 200,000 euros in some cases. Massive retailers like Desigual and Adidas pounced on the opportunity to setup flagship stores in one of the world’s most attractive city centers, displacing the dozens of family-run toy stores and sweets shops and galleries that made this property so valuable in the first place.

All of this is enough to leave locals wondering whether Barcelona still belongs to them. For the past few years, tourism has ranked as the number one concern of Barcelona residents. Every few months, that simmering concern boils over, prompting protests and worker strikes and entire political movements. Ada Colau’s overnight ascendance to the mayorship of Barcelona was based largely on her promises to take on the multi-headed beast, but her political future is in doubt after failing to stem the tide of transformation gripping the center of the city.

Newspapers overflow the issues of the day: Rents Skyrocket! Robberies Hit All-Time High! Citizens Protest New Hotel Openings! Talk to the people living in the heart of Barcelona and they’ll tell you they feel less like citizens and more like unpaid actors in the tragi-comedy of this city’s transformation.

These aren’t issues unique to Barcelona—in an increasingly accessible world, cities like Venice and Prague and Kyoto are all grappling with identity crises. How do these extraordinary places open themselves to the world without losing their soul? And what role does the government play in safeguarding a city’s DNA?

The making of a great city, like the making of a great civic institution, is equal parts science and art. The science belongs to the city planners and politicians who define the rules of engagement; the art comes from the citizens, who fill the urban canvas with a million tiny brushstrokes. Both Barcelona and the Boqueria have gotten to where they are today because both sides of this equation have done their part—with that special Catalan blend of pragmatism and innovation—but now they have been confronted by a new force that no one truly understands.

Barcelona and the Boqueria: two institutions that have fallen victim to their own beauty. It’s clear to anyone paying attention that without intervention, they will lose the people and the places that made them so beautiful to begin with.

At the center of these big issues is Agustí Colom, the councilor of Tourism, Commerce, and Markets, a job title that feels almost surreal in its sprawling scope. Colom has a lot on his plate these days as he and his team work to balance the push and pull of a tourist economy, and he speaks with the speed and efficiency of someone who’s already late to the next meeting. The Boqueria lies at the physical and emotional core of Colom’s task.

“The Boqueria is a special market,” says Colom. “One of the main challenges is to keep tourism from affecting the regular clients—to keep the Boqueria from turning into a theme park.”

Colom runs through a number of the measures they’re exploring as safeguards for the market, including capping the percentage of take-away food sales from a given stand. I point out that the Boqueria has been under the siege of tourism for nearly a decade now, and that many of the vendors believe that the city lost its chance to effectively control the chaos. “I realize the situation is more complicated now than if we had acted earlier but we’re obligated to at least try. It would have been better to implement preventative measures, but it’s not too late.”

Colom talks a lot about a market’s ability to adapt—both to the ever-shifting demographics of the neighborhood it occupies, but also to the demand that keeps its vendors solvent. If a product can’t sell, replace it with one that does and move on. Complicating matters, though, is the official strategic plan of the government, the same one that runs front and center on the municipal markets web page, which stipulates that Barcelona’s municipal markets are more than just commercial centers, they are “a source of dissemination of Catalan food heritage.”

Related Reads

When I ask Colom if pizza and crêpes and potato-chip-crusted hot dogs qualify as components of Catalan food culture, he acknowledges that some of the foods on offer at the Boqueria are less than ideal. It would be one thing if Barcelona had a history of street food that it could draw from to appeal to the transient client, but the idea of walking and eating is anathema to your average Spaniard, so the foods on offer invariably veer well outside the Iberian peninsula.

If it’s tricky to control life inside the market, regulating the market’s role in its surrounding environment is even more challenging. “The markets are a reference point for the life of the neighborhoods of Barcelona,” reads the official market manifesto, “and they provide an experience not just of buying, but also of coexistence with the citizens.”

Few cities in the world are more dependent on market life than Barcelona. Colom and his office manage a network of some 40-plus municipal markets that powers the kitchens of the Catalan capital. In total, they generate 62 million visits and over $1 billion in sales annually. These aren’t weekly farmer’s markets or modern concepts that have sprung up during the rising tide of foodie-ism, but well-worn institutions that have anchored neighborhoods for centuries. They owe their prominent place in Barcelona life not just to dedicated cooks, but to years of effective planning and consistent upkeep —including more than $150 million in recent renovations to many of the city’s most emblematic markets, including the Boqueria.

In turn, these markets give more than the daily bread; they give life and culture and refuge and character to a neighborhood. From them spring so much of a barrio’s DNA, of its daily rhythms and collective memory. They have become mirrors of their neighborhoods, and their neighborhoods of them: the Mercat de Barceloneta, with its salty collection of fishmongers and smell of the Mediterranean; La Concepció, positioned in the heart of the Eixample Dreta, soaring and grand like the neighborhood that houses it; the crumbling ruins and the rainbow dragon-scale roof of Santa Caterina, a bright, funky reflection of the boutiques and studios and deep history of the Born neighborhood that surrounds it.

They once called Sant Antoni la Boqueria de los pobres, the poor man’s Boqueria, but after a two-decade renovation that has yielded a mix of modernist architecture and art-curated food stands, the name has reached its expiration date. Sant Antoni’s rebirth is both a symptom of and a contributor to the rise of the surrounding neighborhood, which is now one of Barcelona’s most coveted addresses.

But the Boqueria has always been different, says Oscar Ubide, who as managing director of Barcelona’s star market has been representing vendors there for more than 15 years. (Short description of his job: Keep people shopping at the Boqueria. Long description: Balance the billion forces exerted on the market—the tourists, the economy, the changing times—and find a way to keep everyone happy and making money.) “The Boqueria was never a neighborhood market,” he says. “It was always something bigger.” Not a barrio market, but a city market—its challenge is not just to reflect the complex dynamics of the Ciutat Vella where it’s housed, pinched between the Gothic Quarter and the Raval, but to evoke the soul of a beautiful, complicated city. In that way, the Boqueria plays the role of microcosm convincingly: a cacophonous, cosmopolitan collection of old and new that feels forever on the verge of losing what makes it so great to begin with.

Related Reads

From his office, perched two stories above the Boqueria, Ubide monitors the daily rhythms of the market. More than 55,000 people pass through the Boqueria each day, representing a staggering sprawl of cultures, languages, and expectations—and challenges for Ubide and his team.

Ubide is a pragmatist, by nature and necessity. Ask him a question about the direction of the Boqueria and he’ll respond with a question of his own: What are you having for dinner tonight? Most people these days can’t answer that question, he says. His point is that people don’t shop the way they used to—if you don’t know what you’re going to eat tonight, you’re probably not shopping at a traditional market. He wants people to adjust their romantic visions of market culture for the less-sexy reality of modern urban life, one where convenience trumps tradition.

“When I was a kid, my mom would know what we were going to eat every day of the week. Monday: lentils. Tuesday: stew. She’d go to the market twice a week and buy all her ingredients for the upcoming meals. But that’s not what people do anymore.” Contemporary eating habits, says Ubide, are as much to blame for the Boqueria’s transformation as tourism.

He speaks like a man accustomed to being on the receiving end of criticisms and complaints. He hears them from all ends (the neighbors, the city, the merchants themselves) about all topics (the market makeup, the crowds, the tough economics). A good part of his job is methodically dispelling people of what he believes to be misunderstandings about the Boqueria.

No vale la pena, they say—it’s not worth the effort.

“A lot of people say they don’t come to the market anymore because there are too many people. I have photos from a 100 years ago, and the Boqueria was much more full then—all women with their shopping carts. I remember going with my mom when I was young and you’d get in a line behind 15 other women and spend 30 minutes at one stall. You go now to any stand in the market and you can buy without waiting.”

And he’s right—it’s exactly what I do a few times a week, and if you time it correctly, you can work through an entire shopping list in 30 minutes and escape with the same ingredients being used at Michelin-starred restaurants around town. You can still find stands that sell nothing but mushrooms, nothing but eggs, nothing but the odd bits of animals. Which begs the question: If great stands still exist, and the lines are shorter than ever, what keeps locals from coming? Maybe it’s something more ephemeral than the crowds—a general feeling that the market is past its prime. No vale la pena, they say—it’s not worth the effort. Locals would rather wait in line with locals than dodge selfie-shooting smoothie-slurping tourists. Market runs have always been a pain in the ass, but the specific kind of pain in the ass the Boqueria has become isn’t one that most Catalans will endure.

It’s at the heart of what seems to frustrate Ubide most: locals who demand the Boqueria maintain its traditional character, but who don’t shop there themselves. “If you’re not shopping here, who are we maintaining if for?”

Ubide maintains the posture of a capitalist, governed by an abiding belief in the market’s ability to self-regulate. If a product no longer sells, then it doesn’t have a place in the Boqueria. “Of course we’d prefer a market that sells all fresh products—everyone prefers that. But it’s not realistic. Supply needs to match demand.” He estimates that if he were to stick steadfastly to a traditional market concept, he’d have to close 160 stands at the Boqueria tomorrow to make it work.

So what do the people of Barcelona prefer: A traditional market that barely survives, or a tourist-friendly market that locals ignore?

“There are two Boquerias,” Pau Arenós, longtime restaurant critic for El Periódico, tells me between bites. “The market for us, and the market for them.”

It’s an analysis I’ve heard a lot in the years I’ve been coming here, but it means a lot coming from Pau, one of Spain’s greatest food writers and an accomplished cook who has shopped here since he was 20. “The beauty of the Boqueria as a cook was coming here to wander around and get inspired. You can’t do that anymore.”

At the end of his fork is a piece of history—a gelatinous bit of braised cow’s foot, part of the mythic cap i pota of Pinotxo, the “head-and-foot” stew served at the Boqueria’s most famous bar. Pinotxo is one of the few places where the two markets coexist, where the long, busy bar doubles as a bridge between two distant worlds. At the end, Juanito, the smiling face of the Boqueria, greets customers just as he’s been doing for more than 60 years. To our left, a family of Koreans drink café con leche and pick at a tortilla; to our right, a Catalan construction worker sops up the last of his braised beef with the heel of a baguette and washes it down with a glass of red wine.

The few people who still do it right, who do it like Pinotxo, say Pau, “do it out of a sense of pride and responsibility passed down from generation to generation. It’s an inheritance, he says, but the line of family-run operations has been replaced by investors looking to capitalize on Barcelona’s big moment.

“It’s all part of a larger Disneyfication of the city. We’re all on a stage. And in the Boqueria especially, you don’t know what’s real and what’s fake.”

Braised cow foot: real; coconut-lychee-cranberry smoothie: not so much.

Nobody remembers who was the first to sell smoothies at the Boqueria. Or if they do remember, nobody seems eager to take credit for it.

An ever-growing army of plastic cups that paint the market a psychedelic swirl of orange and green, pink and purple.

The idea, undoubtedly, came from a very simple realization: Tourists don’t buy vegetables. They don’t buy fish or pork chops, snails or mushrooms. They sure as shit don’t buy monkfish or mollusks, chicken or chickpeas or chicory. They need something they can hold in their hands, consume in the moment before they move on to the Sagrada Familia or the sands of Barceloneta. Sure, savvy travelers know that a market is the perfect place to build a picnic of local products, and an ideal spot to find gifts for friends and family, but most visitors aren’t thinking beyond their next bite. For them, smoothies gave them a simple way to connect to the Boqueria.

Today, much of the Boqueria runs on liquefied fruit—an ever-growing army of plastic cups that paint the market a psychedelic swirl of orange and green, pink and purple. At Sprimfruit, near the market’s main entrance, they sell so many smoothies that they run them through giant plastic tubes like some marginally-healthier version of the Wonka factory. Some have bet the entire farm on pulverized produce; others have tried to keep selling fresh apples and bananas and strawberries alongside their fluid counterparts, but with diminishing returns. I’ve watched over the years as the fruit itself is subsumed by its byproduct.

More than replace much of the market’s supply of fresh fruit, the smoothies set off a chain reaction across the market. Vendors, already suffering from a lack of local clientele, looked for ways to transform their raw staples into processed profit. At first it happened in small doses: charcuterie stands sold skewers of jamón and chorizo, a few fish stalls offered oysters ready to be shucked and slurped. But the economics are such now that if you don’t have something to offer the tourist, your days in the Boqueria are probably numbered.

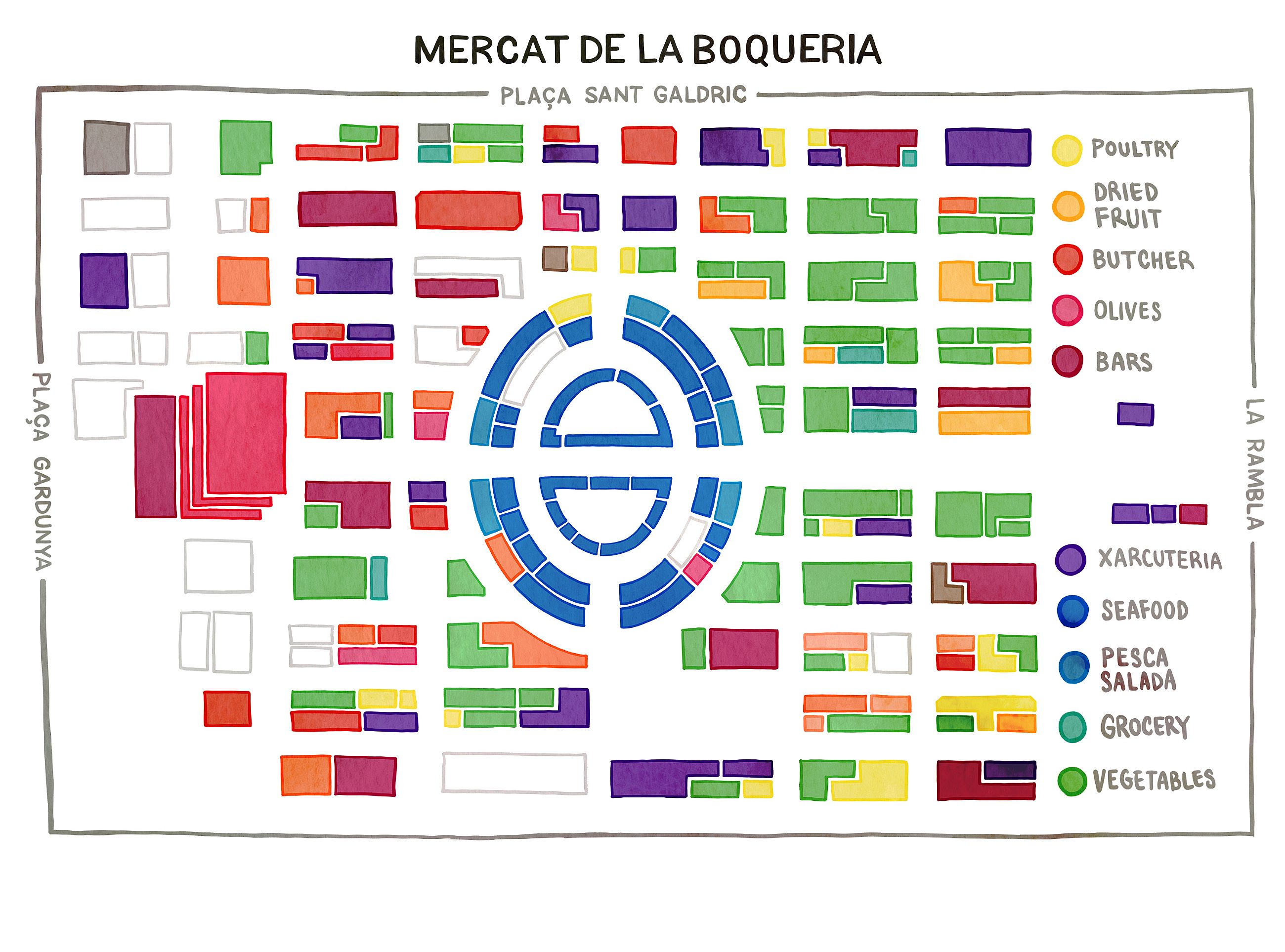

Just ask Inmaculada Jiménez Fernández, who works at Pesca Salada Pujamar. Stall 729 sits on the edge of what I call Takeaway Alley, the area of the market most radically transformed by tourism over the past decade. As a classic Mediterranean market, the Boqueria has long been organized to have fresh fish at its very center, with the stalls that form a ring around it selling seafood products—cured anchovies, canned seafood, bacalao (salt cod), and salazones (dried and cured fish products). Think of it like a corollary to other protein pockets of the market, where pork butchers and charcuterie vendors find themselves positioned side by side. Once upon a time, this section of the Boqueria burst with the bounty of the Mediterranean and the Catalan countryside. Now, it’s a bottleneck of cheap calories dispensed by stands that have largely given up trying to partake in the traditional market economy.

When Inmaculada’s family took over stall 729 in 2009, they specialized exclusively in cured and salted fish—stiff ivory planks of salt cod in various stages of desalination; brown fillets of anchovies shimmering in their olive oil tombs; mountains of mojama, rosy slabs of tuna belly salted and dried for months, the jamón of the sea. They did a brisk business with the Catalan customers who appreciate a few extra depth charges of umami on their dinner table.

“This was all locals nine years ago,” says Inmaculada, hands on hips, surveying the crowds shuffling past. “If you saw a foreigner, it was because he was lost.”

But the market demographics began to shift not long after they took over the stall. She claims much of that grew out of la crisis, the economic crises that crippled all businesses in Spain for nearly a decade. According to Inmaculada, local customers didn’t have the disposable income to afford first-rate market products. And when local faces were replaced more and more with foreigners, they saw the future in stark terms: evolve or die.

What does a vendor with a surplus of salt cod on hand do in a market full of foreigners who couldn’t tell a filet of bacalao from a bar of soap? You soak it, shred it, mix it with flour and egg, garlic and parsley, and fry it into golden crisp golf balls. Proving once again that age-old Spanish axiom: When life gives you salt cod, you make donuts.

When life gives you salt cod, you make donuts.

Today, approximately twenty percent of the real estate of Pujamar is dedicated to take away food—not just bunyols de bacallà, but crispy bacalao skin, golden rings of calamari, and other fried seafood snacks. All told, this little slice of the stand accounts for more than 80 percent of Pujamar’s sales.

To understand the rhythm of the Boqueria in 2018, you need only position yourself at 729 for a few hours and watch what it takes to make a business out of bacalao. Inmaculada positions herself at the edge of the stand and actively engages any market-goer that shuffles past her. Not the brusque Que quieres? or Que te pongo? of the traditional market barkers, but a more gentle Where are you from?, a question that, when delivered with sweet curiosity, almost everyone feels compelled to answer.

And Inmaculada is prepared for any answer. From Rome? She switches immediately to a sing-songy Italian: Perfetto! Oggi abbiamo polpette di bacallà. Just in from Moscow? оладьи из соленой трески. On a trip over from Tokyo? Ohayo gozaimasu!

She changes language every few syllables, moving effortlessly from the Far East to the central Europe to North America. In one thirty-minute span on a Thursday morning in October, I witness Inmaculada make sales in nine languages: Russian, Portuguese (which she can vary depending if her customers are from Porto or Brasilia), German, Polish, Greek, Hebrew, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, and English.

Along the way, she’s learned a lot about the world, her commentary a news ticker of geopolitical observations. “The Russians used to come here with suitcases they’d fill with our products, but that changed after the price of oil fell a few years ago… You never know what you’re going to get with the American customers… I never try to guess with Asians. I’ve learned the hard way that the Japanese and Chinese don’t like being mistaken for each other.”

She claims she doesn’t have any geographical preference for her customers—Germans are as likely as Koreans to fall under her spell—but she does have a few groups she’s lost confidence in: backpackers, for one, who only want to spend a few euros on a baguette and a hunk of cheese. But others, too: “Cruise ship tourists are no good. They come with a guide and spend 15 minutes here. Plus, they’ve been eating from the buffet on the ship so they never come hungry.”

The last sale of the morning comes in her native Catalan. The man—mid 50s, black leather jacket, four-day beard—picks out a slab of bacalao from the bath where it’s been soaking.

Inmacualada wraps up the fish, takes the money, and wishes the customer a good day.

“That makes me happy.”

The market is a metronome. Its rhythms and rituals, its cadences and calories set the schedule for the day.

The market is a measuring stick. Through the quality of its offering, the cost of its contents, the pluck of its people, we can look out across the world and find our place in it.

The market is a mirror. In its people and products, its economy and ecosystems, we see the reflection of the city itself. The market isn’t just a nexus of commerce, but the apotheosis of our values.

Think: What does Nishiki Market, its barrels of vegetables preserved for an eternity in baths of salt and cloaks of miso, its tenth-generation vendors of exalted powders, its shops of still-warm santoku steel, say about Kyoto?

Think: How better to understand modern San Francisco than through the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market—the nixtamalized tortillas, the $4 peaches, the deluge of shade-grown coffee, the crew of vagabonds and homeless, the most local product of all, kept to the margins?

Think: Is Mexico City still Mexico City without the Mercado de la Merced pumping blood into its organs?

The market is a map. Every piece inside it signals where we’ve been or where we’re going.

Look around the Boqueria and you’ll find the timeline stretched out across the market floor: the milk-fed goat legs, the bundles of baby leeks, the premade burger patties, the pizza oven, the blender.

Maybe this shouldn’t sting so much. After all, the modern world is one of compromise. Venture off in any direction from the Rambla and you’ll see the evidence everywhere: We’ve traded handmade leather shoes for neoprene Nikes, the old family candy shop for the seventeenth ice cream parlor, lunch for brunch.

As the transformation gathers force around you, do you stand your ground, or do you try to find another way?

All we can do is try to survive.

Willy, the vegetable vendor who’s been selling me Monalisa potatoes and Figueres onions since 2002: “It’s too far gone now. There’s no turning back. All we can do is try to survive.”

Marco, the fishmonger, scaling a kilo of sardines: “This is what I know, fish. I don’t know sushi. I don’t know oysters.”

Gloria Ricardo, vendor at Puerto Latino: “It’s become more than a market. We sell what people buy—that’s the one way to survive. They love the empanadas. They love the beer.”

José the butcher from Soler Capella, purveyor of protein to the city’s high-end restaurants: “Please tell the rest of the world: There are still great products here, but they’re disappearing. Our clients are disappearing.”

“I’ve lived through five great changes over the years,” says Laura Besora Cruz, who’s been running the Balbina Ampurdanés produce stand since 1984, “the economic crisis of 1990, the boom of the ‘92 Olympics, the waves of African and South American immigration of the early 2000s, the economic crisis of 2008, and now, the last big change: tourism.”

Through each wave, she’s adapted and survived. When African and Latino immigrants came, she added yucca and plantains and avocados to her roster of produce. When the crises came, she turned to harder fruits that lasted longer on the stand. When the tourists came, she did like everyone else and began to introduce that fruit to the blades of a blender.

“No one is here to buy fresh fruit and vegetables. Put yourself in their shoes. What would you do if suddenly your produce or your chicken stopped selling? Would you do what you need to do to survive? Instead of plantains now, I sell fruit salad. Instead of strawberries, I sell smoothies.”

And yet a full 80 percent of her stand is dedicated to fresh produce: mangoes from the Canary islands, the Raf tomatoes of Almeria, tight-lipped artichokes from El Prat.

“I keep going, hoping that it might one day come back. But I don’t think we’ll see the locals return. We lost them to the supermarkets.”

Her family history runs deep in the Boqueria. Her great-grandmother started selling fruits and vegetables in 1908. Her brother operates the stand right next to her. But she sees the end on the horizon. “I don’t have any kids. When I’m done, I’m selling it.”

I spend an hour at the stand, watching the foot traffic, hoping to see some signs of a fruit-and-vegetable future.

At one point, as a crowd of Chinese tourists start plucking smoothies from the bed of ice, she shoots me a look: You see?

“There was an important phrase we used to say around here years ago. We used to ask each other, ‘Did you work well today?’ and we’d always say yes. ‘When the sun rises, it shines on everyone.’”

She pauses for a second to sell a smoothie. She pockets the coin and turns back to me.

“Not anymore.”