The artist behind Tunisia’s feline cartoon phenomenon talks about taboos, resistance, and her country’s stalled revolution.

Nadia Khiari first drew “Willis from Tunis” on Jan. 13, 2011, doodling the cat cartoon character into existence during Tunisian dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s final speech. After weeks of Tunisians rioting in the streets, he announced an end to censorship and promised other long-awaited freedoms. He fled to Saudi Arabia the next day.

Khiari, 44, was a successful painter when Tunisia’s so-called Yasmin Revolution started at the end of 2010. The protests, which inspired the Arab Spring movements in Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain, and elsewhere, were sparked by the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi in December 2010. That, coupled with long-simmering discontent about living standards, corruption, and censorship, resulted in mass demonstrations and riots throughout the country, ultimately ending Ben Ali’s 23-year rule.

At first, Khiari simply used the Willis character (or “Cat of the Revolution”) to vent anonymously on Facebook about her thoughts on the Arab Spring. But the drawings were widely shared, and today her Willis pieces are a popular record and commentary on Tunisian and regional current affairs, casting a critical and humorous eye on previously taboo topics such as women’s rights, police brutality, and homosexuality.

Seven years after the Arab Spring, her cartoons also express Tunisians’ frustration and despair with the current government’s backsliding on the long-awaited changes promised by the revolution: freedom of speech is again being eroded, corruption is still rampant, and there have been few improvements to living standards for most Tunisians.

Khiari, who teaches at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Tunis, no longer paints, but her cartoons appear in Siné Mensuel, Courrier International, and Zelium. Journalist Franziska Grillmeier spoke with Khiari over lunch in Tunis about resistance, vulgar words, and the state of the revolution.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Franziska Grillmeier: When would you say you became politically active?

Nadia Khiari: My family is not political at all. My grandfather was very much of his generation. My only relationship to politics during Ben Ali’s rule was with the police. Politics was something we couldn’t do anything about. We were not allowed to talk, to criticize, to debate. I was interested in politics, but I was no activist. My activism began with the revolution.

Grillmeier: Do you use art as a tool of resistance?

Khiari: When I go to a demonstration and see my cartoons in the streets, then I know: this is why I’m doing it. Because in that moment, people don’t care about me, they care about the cartoon, and it expresses something they feel. Then I know that my opinion is shared by others.

Grillmeier: The number of self-immolations tripled after the revolution, especially in smaller towns. In one of your cartoons, you drew two cats taking a selfie while someone is on fire behind them. What did you want to express in this cartoon?

Khiari: People care about their own security. They talk about themselves and forget what’s going on in the whole country. The cartoon is not about, for example, Radhia Mechergui [a woman from Sejnane who set herself on fire in November 2017], but that whole gap in Tunisian society. Since 2011, hundreds of people in Tunisia have set themselves alight, but in the city, it’s just a short footnote on the radio now. Everybody talked about Mohammed Bouazizi, but we didn’t hear about the many people who have done it since.

Grillmeier: Because people got used to hearing about it happening?

Khiari: The fire symbolizes the pain the people carry inside of themselves. Among all the other reasons, to come to the point where you set yourself on fire in public—it’s a very public form of protest. People want to be heard. But in the wealthier parts of the cities, people think they’re crazy, just people who burn themselves. That’s all.

Grillmeier: After the revolution, was there a decline in solidarity between different social groups in Tunisia?

Khiari: In the summer we have big problems with our water supply. Whole villages are cut off from wells for weeks and yet, at the same time, people in Tunis are throwing pool parties and posting the pictures on social media. People are disconnected from each other.

Grillmeier: Do some people regret the revolution?

Khiari: It drives me crazy to hear that some people are nostalgic about the Ben Ali era. I published the “Manual for Perfect Dictators” last year, which contains lessons on how be a good dictator. I wanted to remind people about the 23 years of Ben Ali’s dictatorship, because people forget. Even before Ben Ali, we were in a dictatorship under Habib Bourguiba, and his final years were awful, too!

Grillmeier: Are you hopeful about the new generation?

Khiari: It is my only hope. They are the future.

Grillmeier: What do the young in Tunisia wish for?

Khiari: They want to be in love, to have a good job, and to raise a family. But they can’t even find a job to begin with, so how can they start rebuilding the country?

Grillmeier: Many young people look for alternatives. Around five thousand people left Tunisia last year, via the Mediterranean…

Khiari: If I were 20 years old and an artist today, I wouldn’t be here. I would take a boat to Lampedusa. I have friends, who are young and are leaving, and I can’t blame them.

Grillmeier: Do you think there’s a focus on helping young people find a job?

Khiari: The president is very old. He doesn’t speak the language of the youth. He is 92. Half of the population is under 30, and this guy is 92. Since the revolution, I haven’t seen a change in the ministry of culture.

“If you compare Tunisia to Syria or Libya, we are O.K. We are not at war. But why can I not compare my country to Iceland?”

Grillmeier: When German chancellor Angela Merkel visited Tunisia last year, she called the country a “lighthouse of hope.” How do you feel about this perception?

Khiari: If you compare Tunisia to Syria or Libya, we are O.K. We are not at war. But why can I not compare my country to Iceland?

Grillmeier: Tunisia has a unique status as the only country to have emerged from the uprisings of 2011 as a genuine democracy, and has also made some strides in women’s rights. The first national law to combat violence against women was passed in July 2016. Would you say there is progress?

Khiari: A form of state-sponsored feminism is still going on. The state uses women’s rights like window-dressing, to show off its best side. In reality, we are a long way from having the rights we should. In some areas, whole families rely on one female breadwinner. And women still get only half the inheritance men do.

Grillmeier: Many Tunisians say the one thing that came from the revolution was that they don’t have to fear expressing their thoughts anymore.

Khiari: It is really, totally different than before. Before we were constantly paranoid. Under Ben Ali, I would never be sitting here talking to you. There was no politics over the coffee table or in the streets, you would talk at home and take out the battery of your phone. We were paranoid, because we knew people who said what they thought were going to jail all the time.

Grillmeier: And this changed immediately after the revolution?

Khiari: After the revolution, the energy was incredible. It is totally different. Now we can talk about sexuality, homosexuality, torture, radicalization, religion, and health care. I never thought it would be possible, in this country, to go to a jail and run cartoon workshops, and talk about homosexuality and religion.

Grillmeier: Is this a new project?

Khiari: For about a year I have been working with the international network Cartooning for Peace, holding workshops in prisons in Tunisia. We plan to exhibit cartoons inside the prisons, and afterwards we will run workshops on drawing. We need to change people’s view of prison, and to offer something to the prisoners other than religion.

Grillmeier: So things have changed?

Khiari: Ever since I can remember, we had to put a picture of Ben Ali in every shop, grocery store, and supermarket. Before the revolution, I had a gallery where we held some exhibitions with young artists. The police came regularly to ask me about the Ben Ali portrait, which I never hung; I would just tell them that the portrait was at the framer’s. The portrait was at the framer’s for four years!

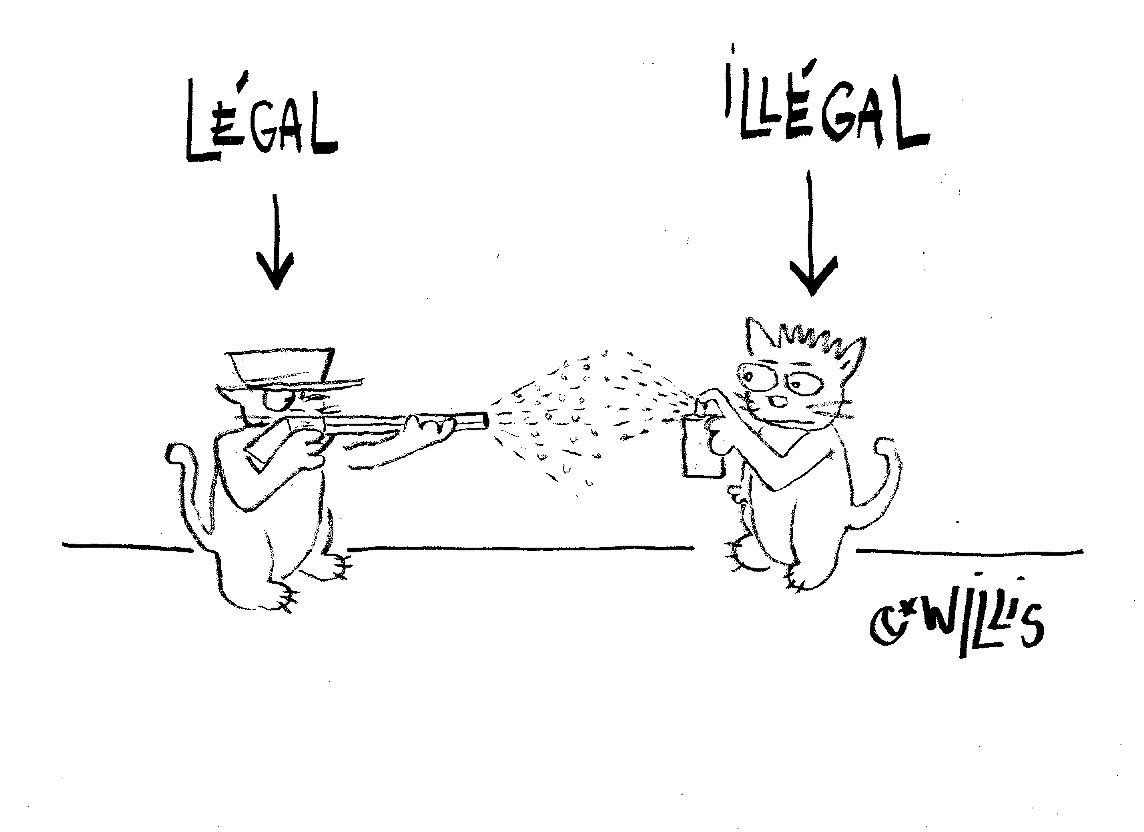

Grillmeier: In 2015, the government drafted a law to protect the armed forces after policemen were regularly attacked on the streets. This law would make the unauthorized filming of a policeman, for example, beating a demonstrator, punishable by two years in prison.

Khiari: If the law passes, I won’t be allowed to draw policemen in my cartoons anymore.

Grillmeier: Which would be a blow to freedom of expression?

Khiari: Yes. We once again have heavy restrictions on freedom of expression, and that started before the state of emergency following the attack in Sousse in 2015. If you have money, you don’t have problems, but if you don’t have money you’re on your own. In general it’s still the case that if you have money in this country you have no problems. If you don’t have money, you have fewer rights.

Grillmeier: Has the economic situation deteriorated since the revolution?

Khiari: Before the revolution, we didn’t have any statistics; people said what they wanted. But I guess it’s worse than before. Back then, there was tourism and foreign investment. Tourists don’t come anymore. The problem is corruption. Before the revolution it was Ben Ali and his family, but after, it was not only this family, but everybody who wanted a piece of the cake.

Grillmeier: When you publish something, do you get a direct response from social media?

Khiari: I never comment or reply to messages, because I want people to express themselves without my interference. If they like my work they like it, if not then that’s O.K. too.

Grillmeier: Was there any point when you felt you wanted to stop drawing?

Khiari: It is such a pleasure to be a pain in the ass. I cannot stop. The day I discover that I’m not disturbing anyone, that’s when I’ll stop.

Grillmeier: And the ideas keep flowing?

The thing that takes time is the idea, not the drawing. The thing that takes time is getting good information, because we have so much false news that it’s difficult to find good, verified information. I would never want to make a cartoon based on a rumor.

Grillmeier: What’s left of the revolutionary energy today?

Khiari: It evolves. There was a very special energy from January 2011 until that October, with the election. It was a perfect moment for me, because the dictator and his family were gone. We were full of dreams. But then the elections arrived too fast. We were not in a hurry. After the election, we got a big slap in the face. Ennahda, the Islamic party, was elected, and some of Ben Ali’s ministers continued to work in parliament. In 2011, we were full of dreams, and we’ve realized that it’s hard to have dreams like this. We have had something like nine governments in seven years, and nothing has changed. What disturbs me very much, we were supposed to have regional elections on Dec. 17 and now they’re saying, no, in March perhaps. [These municipal elections are now scheduled for May 2018.] Why? Where in this world, in a democratic country, can we change the date of an election like this for no reason?

Grillmeier: What was the reason?

Khiari: They said they weren’t ready.

Grillmeier: Do you feel that this anger could lead to another uprising?

Khiari: Oh, I hope so! We have to do it again! We have the same guys in power, the same situation, the same poverty and unemployment.

Grillmeier: On the way here, I saw a lot of graffiti expressing solidarity with Gaza.

Khiari: It’s an important code in the Arabic world. Even if they don’t actually do anything, people spray those messages all over. This solidarity strengthens your own identity. The Islamic identity of this country is one reality, but it’s not the only one.

Grillmeier: Is Willis, your cartoon, a form of identity for you?

Khiari: When I started drawing this character I was anonymous, and people thought I was a man. My humour was perceived as masculine. I used a lot of vulgar words, because I talk like that. And I also got comments—that I’m macho, and that if I were a woman, I would never say these things. It was very funny.

Grillmeier: How do you choose what subjects to draw?

Khiari: The most important thing for me is to draw in response to topics that make me angry or of which I’m afraid, because I feel that if I do that, and I can laugh about it, I overcome my fear.

Grillmeier: Do you have a cat yourself?

Khiari: Willis is my cat. Wild, not obeying at all. I like it.