How Mark Maryboy might have changed rural Utah—and America—forever.

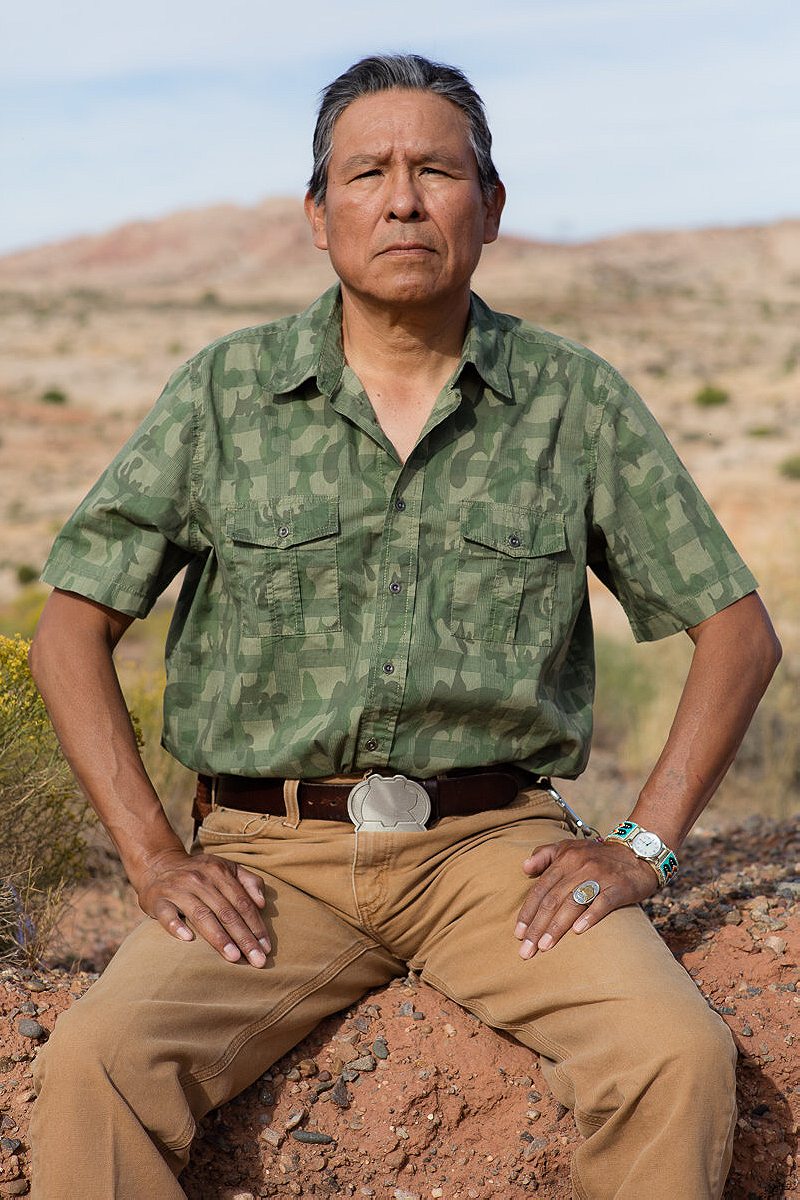

Mark Maryboy walked from his home near Montezuma Creek, Utah, to his beige 1993 Dodge Dakota on a dry morning in 2010. His stride was long but rapid, just beginning to hint at the unsteadiness of old age. His sinewy, six-foot-tall form was hidden by the respectable southern Utah uniform of durable jeans and a tucked-in T-shirt.

The truck released dust from the road as he began his drive into a remote reach of the Utah strip of the Navajo Nation reservation. On the passenger seat, a neatly folded map, pencil, and hand-held tape recorder rattled with the shake of the car. After nearly three hours of careful navigation, Mark pulled up to the home of an elder, where he would spend about four hours gathering information vital to his long-running efforts to protect the rural land he and his people hold sacred.

“Yá’át’ééh,” he said, greeting the elder in Diné, the Navajo word for their language, culture, and the original name for their people.

Mark spread open the map. On it, the forested Abajo Mountains rose in the east. The red rock expanses of Indian Creek sprawled over the north and the regal formations of Monument Valley stood tall in the south. The grassy meadows and plunging canyons of Cedar Mesa cut through the middle, and two buttes took the center of it all, unmistakably resembling the ears of one of the area’s oldest inhabitants—the bear.

Mark explained the reason for his visit and asked the old man to circle the place of his birth on the map. He asked the man where his umbilical cord was buried, a traditional Diné practice, where his grandfather was born and where he had gathered herbs for medicine or rituals. Mark asked the old man about spiritually important sites, locations of ancient ruins and where certain animals live across the seasons, like bighorn sheep, white-tailed deer and bears. Mark wanted to know what the man had done to care for these sites, their artifacts, plants and wildlife. The elder was grave, answering slowly and softly in their native tongue. He would not have shared this information with an outsider.

Before Mark left, the old man performed a blessing. It was, in a way, a prayer for a good outcome from entrusting Mark with this precious information.

Mark later painstakingly transcribed and translated the man’s knowledge into a key to the map. Round River Conservation Studies, a nonprofit working with the Navajo Nation, analyzed the information Mark gave them and integrated it with data gathered by anthropologists and scientists on the geology and endangered wildlife of the area, as well as federal information on land usage.

After about three years of research and another four years of effort at the county, state and federal levels, the land outlined by Mark was designated as Bears Ears National Monument by President Barack Obama on December 28, 2016. The 1.35 million acres of land were to be guarded from uranium, oil, gas and other natural resource extraction. Its ancient ruins were to be provided more robust legal protection and co-management authority of the land was granted to an inter-tribal commission, affording five tribal nations more influence over federal public land management than native nations had ever been given in U.S. history.

But less than a year later, Obama’s successor, President Donald Trump, slashed the monument’s acreage by 85 percent, claiming his decision was a reversal of federal overreach. Trump also reduced the size of Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This unprecedented move exposed the land, once again, to private interests in natural resource extraction and weakened the legal protection of ancient ruins. Three lawsuits have since been filed, contesting Trump’s decision, which has come under scrutiny.

The outcome of the cases could help solidify Obama’s rewriting of government officials’ approach to honoring America’s indigenous heritage through conservation, or it could throw tribal activists back to square one. But without Mark Maryboy, there might never have been a possibility of change at all.

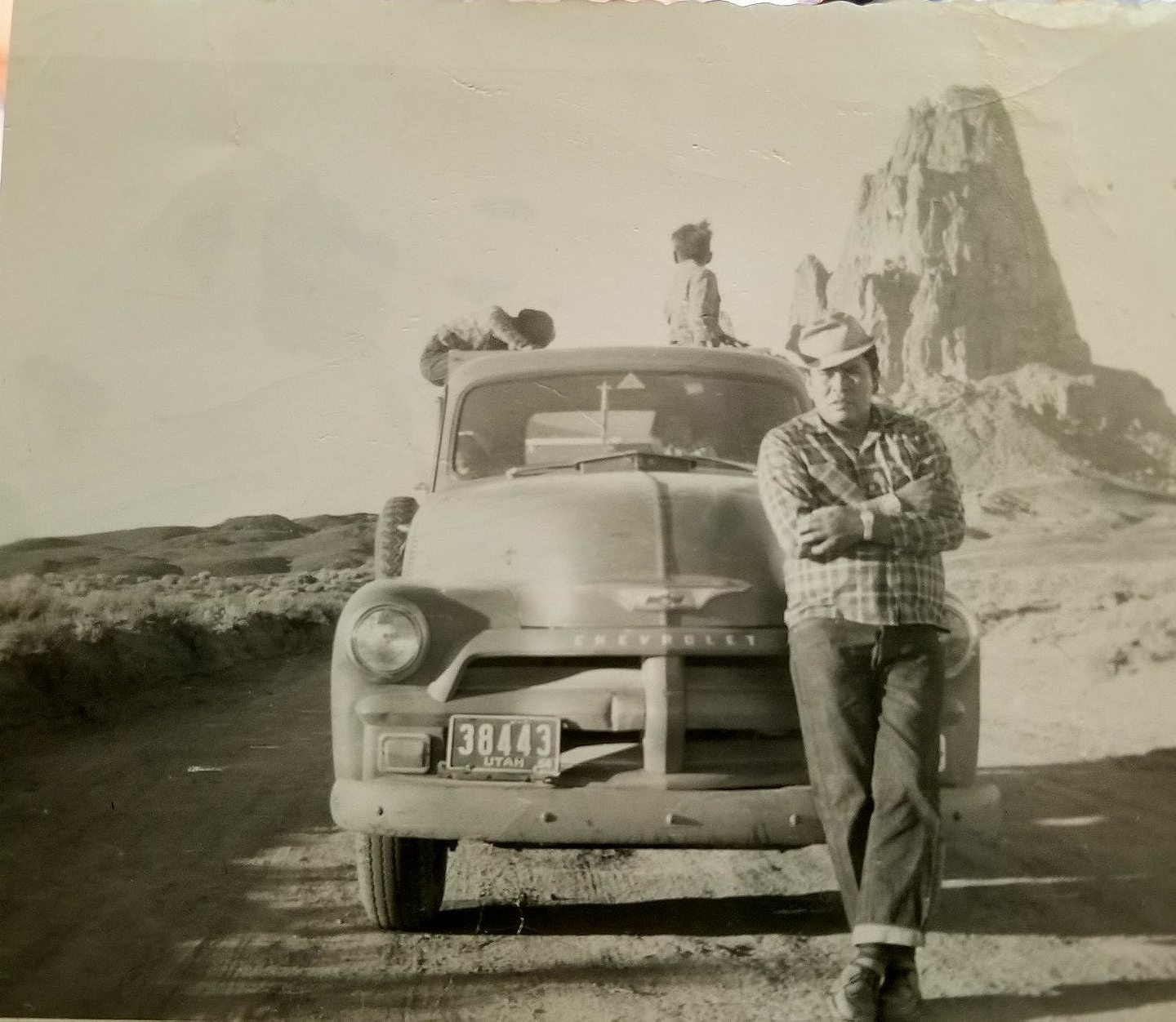

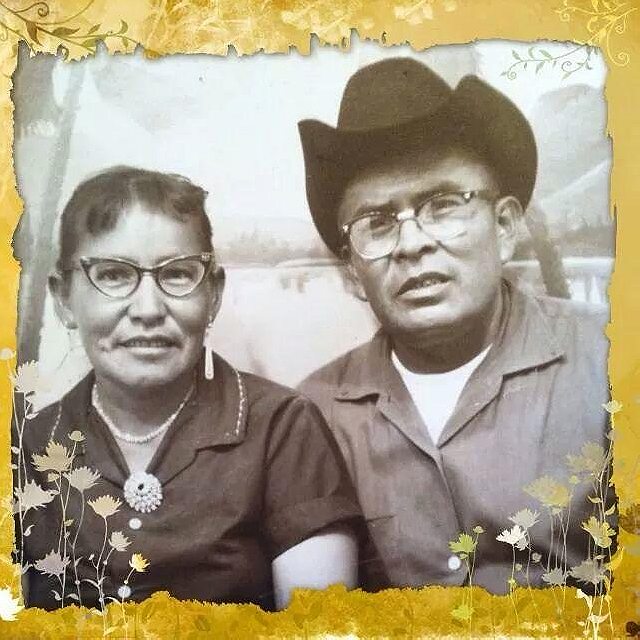

Mark was born on the south side of the San Juan River in 1955, the sixth of John Bell and Clara Maryboy’s eight children. He grew up on the Utah strip of the Navajo Nation reservation, near Bluff, Utah in rural San Juan County.

The Maryboys split their time between living on reservation land in their hogan, a traditional Diné domicile, and in temporary homes near Fry, White, and Allen Canyons. Mark’s father and two oldest brothers were among the scores of Diné men who labored in the uranium mines that bloomed across San Juan County at the height of World War II. Because the locations of the mines were so remote, the wives and children of the miners camped near them to keep their families together.

John and his two oldest sons would return home at the end of each day caked in noxious yellow dirt from the mines. The family would share a warm meal, often pork and beans or mutton stew, and pass the evening hours by the light of a kerosene lantern. Sometimes the children gathered around Clara as she spoke to them, the flickering light illuminating the contours of her youthful face.

On nights like this, Mark listened to his mother intently as she issued to her children the advice she thought they needed to live good, dignified lives. Above all, she implored Mark and his siblings to gain an education, never grow complacent and never forget their roots.

No matter what, Mark remembers his mother telling him, he would always be Diné.

John and Clara took great care to imbue their children’s lives with Diné tradition. On some nights, Clara would take her children outside and teach them how to read the movements of the constellations, about how they indicate the arrival of the seasons, and the appropriate traditions that accompany those celestial changes, like when to hunt or to tell certain Navajo stories.

When John wasn’t working, he would trek for hours through the highlands with Mark in tow, teaching the boy about wildlife, medicinal plants, and hunting. After John shot a buck, Mark would watch as his father butchered it in the bush according to the proper ritual, honoring every bone.

Back on the reservation, Mark and his siblings spent their mornings with Clara as she prepared breakfast for them, often fry bread or scrambled eggs, in the fire at the heart of the family hogan. He remembers his mother telling him, as she tended the embers, the occasional fleck of ash settling on her obsidian-colored hair, that he’d grow up to be a responsible person, and he did. Mark graduated from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City in 1978 with a degree in history and minor in economics. Mark’s father insisted that he learn to work with white people, so he spent three more years in Salt Lake City as an assistant regional manager at KMart before returning to southern Utah.

In that time Mark gained what had remained out of his parents’ reach: the education and knowledge of white American culture that a Native American would need to hold their own in the rural, white-controlled Utah.

Today, Mark splits his time between his family, his business (an environmental consulting firm), and various environmental advocacy projects. This is what he enjoys. But for about two decades following his return home to the reservation, he despised much of his work.

John had suggested to Mark before he died of lung cancer that a Native American should sit on the San Juan County Commission to represent Navajo interests by directing county resources to Native communities for basic public services and infrastructure.

About 49% of San Juan County’s population is Native American, since the county overlaps with Navajo and Ute Mountain Ute reservations, but what John was suggesting was bold. Inhabitants of the county’s reservations are at once members of one of the tribes (which are sovereign nations under U.S. federal law), as well as U.S. citizens and county residents. Should Native Americans, with their nationhood status, be availed of the rural county’s public resources? The answer to that question remains contested to this day. When John uttered his idea nearly four decades ago, it was downright outlandish.

“Growing up in San Juan County, you get that impression that the Anglos, they have an interest which really does not include minority populations,” Mark said.

Mark ran for a San Juan County Commission seat in 1984 and won, having galvanized a bloc of Navajo voters. San Juan County was dealt a shock. Its white residents were hardly accustomed to seeing Navajo people outside of the reservation, let alone in positions of power, with their fingers on the county purse strings.

“Mark was it. He was the tip of sword,” said Scott Groene, a former staff attorney for the nonprofit law firm DNA People’s Legal Services, who saw Mark fighting for resources at heated County Commission meetings in the 1980s.

“There was this extraordinary racism in San Juan County,” Groene said. “… There was clearly a lack of recognition that Native Americans have been there long before the pioneers. And so, you have Mark being the first Native American holding a political position and standing up to Cal Black. It was just extraordinary.”

Mark said his every proposal for more resources and services for tribal communities—or to bolster conservation efforts in the area—was shot down and berated. His position was a difficult one.

“I would go to the County Commissioners’ meeting and basically just hit them over the head with a two-by-four and demand services,” he said.

Calvin “Cal” Black, reportedly author Edward Abbey’s inspiration for the uranium-mining antagonist Bishop Love in the 1975 novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” often sparred with Mark over environmental issues. Black—a member of the Commission for 22 years—advocated for energy development in the county, especially uranium mining, a Black family business that was “one of the great financial successes in San Juan County history.” Black notoriously wore a bolo tie set with uranium, insisting the material is safe. He died of cancer at 61, in 1990.

“From time to time people would come to the Commissioners meetings [to raise concerns], especially Navajos,” Mark said. “I think Utes and Navajos felt a little [more] comfortable now that they had a Navajo County Commissioner [for the first time]. But I noticed that Calvin Black didn’t respect that. When people came talking about certain issues, he would blast them with data, numbers, statistics, and made them look very small.”

Mark said he remembers Black as emblematic of white dismissiveness to Native people, acting amicably before Commission meetings and “belligerent” during them.

“I could not allow myself to be influenced or to be controlled by somebody that was very, very racist,” Mark said. “So immediately [during County Commission meetings] I heard my mom and my dad saying you’re the voice of the people, you need to stand strong.”

Black denied Mark’s allegations of racism.

Mark dug in against Black to oppose energy production in the area, which was more oil and gas than uranium mining by the 1980s, much of it on the reservation. Even if the development could boost the weak, rural economy, it damaged the Earth and was harmful to Native people who lived near extraction sites.

Mark said he also spearheaded the establishment of the Utah Navajo Health System, secured tribal and federal funding to maintain roads on the reservation, built a swimming pool and more for San Juan County’s Native American population. And though he says he despised every meeting, Mark relished his many accomplishments while on the County Commission. He ran and was re-elected three times, serving a total of four terms, a sacred number in Diné tradition. Before vacating his seat, he successfully ran for the Navajo Tribal Council, the equivalent of the U.S. Congress within the Navajo Nation, and served four terms there, too, starting in 1990. For twelve years he held two public offices; one in San Juan County, and one representing his corner of the reservation in the government of the sprawling Navajo Nation.

Mark became known for his unmatched expertise of state, local and tribal government law and policy, and as much for his love of the land where he grew up. So when then-U.S. Senator and moderate Republican Robert Bennett began to consider passing public land planning legislation for San Juan County in 2008, his staff tapped Mark for input. Mark agreed, with caution.

Getting involved in land access negotiations with U.S. public officials has historically proven disadvantageous for Native American tribes, and public land management is a particularly heated topic in rural Utah.

Seventy-two percent of San Juan County’s 7,884 square miles is administered by federal or tribal agencies. In the American West, outrage over what is perceived as economy-killing federal overreach in land management is valuable political fodder. State and federal politicians are known to defer to local officials—the County Commission, for example—for their blessing when it comes to legislating public lands. But Mark saw an opportunity.

After decades of living through and witnessing the exploitation of Diné land and labor—first for uranium, and later for oil and natural gas in the 1980s and 1990s—Mark had the chance to direct the ear of a Congressman to the only people he thought deeply knew the land where he and his family lived, worked and practiced their spirituality, which is inextricable from the land.

Mark decided that should a new land management bill come to pass, it must protect the landscape from development that could harm the land and locals, and its management must be guided by the only wisdom he thought could truly protect the land, the traditional knowledge of Diné elders.

He remembered Clara’s teaching him to never be complacent. Be vigilant and always pay attention, Clara said, or someone could hurt him.

Mark believed he could navigate working with a U.S. Senator. The stakes were high, but Bennett seemed approachable and Mark felt good about collaborating with him. Because there was so much to lose, Mark felt he had to try.

Shortly after the men began working together, Bennett lost his seat in Congress to Tea Party member Mike Lee. But by then, Mark had his own momentum.

He and the Round River Conservation Studies doubled down on their information-gathering efforts, conducting more than seventy interviews in total with Diné elders. Mark and other Native leaders formed the nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah (UDB) to advance their efforts. They produced a book in both Diné and English that condensed findings from Mark’s interviews for the lay reader. UDB signed a memorandum of understanding to cooperate with the Navajo Nation government and entered into what would ultimately prove to be a fruitless joint land planning process with the San Juan County Commission.

Meanwhile, Republican Representative Robert Bishop picked up the rural Utah land planning torch in Congress. Bishop worked with county officials to create the Public Lands Initiative proposal, which Mark felt didn’t take UDB’s input seriously.

Ultimately Bishop’s bill failed to pass the House. But the possibility of more robust management of San Juan County’s treasured mountains, beloved deserts and pacifying acres of dry grass and sagebrush stirred its rural communities into a state of alarm.

Some of the county’s white residents said they use the land’s supply of firewood and game to heat their homes and feed their families. (Many area Diné said the same.) Cattle ranchers, many fifth- and sixth-generation descendents of the area’s first Mormon settlers, were also concerned about access to their ranch lands and water sources. They all believed changes to public lands access could threaten their way of life.

What’s more, the economic booms that natural resource development had spurred over the years had afforded the county costly improvements like paved roads and new schools, which were built in white communities, and many in the small towns of Blanding and Monticello lamented the loss of jobs that resource development once brought the area. They didn’t want new laws to stem future growth.

But for Mark, those things pale in comparison to the sanctity of Earth Mother.

“Probably 90 percent of the land has been destroyed at this point in time,” Mark said. “Some of the remaining—the last pristine areas like Bears Ears—that should be left untouched.”

UDB kept working on a land management proposal grounded in elder knowledge, and animosity intensified between people on either side of the development and conservation issue. At one point, County Commissioner and conservative anti-federal control hero Phil Lyman led an illegal ATV tour through nearby Recapture Canyon, which had been closed off by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) due to its archeological sensitivity, to protest its closure. He was convicted of trespass and conspiracy for the act, spent 10 days in jail in 2014 and was ordered to pay $96,000 in damages.

Lyman’s protest soured Mark and UDB to attempting to work with the County Commission further. But the group had found a way to protect the land around the Bears Ears buttes that San Juan County officials might not be able to thwart.

The Antiquities Act, a federal law that is more than a century old, grants unilateral authority to a willing Head of State to conserve a historically or scientifically significant area as a National Monument. With the help of President Obama’s administration, Mark and UDB could side-step working with the state and federal officials who seemed politically beholden to pleasing white San Juan County.

In 2015, representatives of the Navajo, Hopi, Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indian and Pueblo of Zuni tribes, all of which share ancestral ties to the lands encompassed in UDB’s conservation proposal, formed the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. The tribes crafted a National Monument proposal based on their own land concerns and the boundaries originally laid out in Mark’s map. Together, they submitted a request to President Obama to protect the area by designating it a National Monument. They also asked that the Coalition have co-management authority, equal power to U.S. federal agencies like the Forest Service and BLM.

“The reason we allowed the tribal leaders to take over is because, according to the treaties, they have a government-to-government consultation authority to communicate with the [U.S.] government,” Mark said.

The Obama administration worked closely with the tribes, consulted with UDB and held meetings with anti-monument San Juan County residents over the course of the next year and change. Opponents, primarily from the towns Blanding and Monticello, formed a counter organization called the Stewards of San Juan County and opposed the creation of a National Monument vociferously. They believe that the monument’s creation was a gross overreach of federal power, and because some of the tribes that are members of the inter-tribal coalition are not residents of Utah—but have ancestral ties to the land—they should not have management authority over the land. They are fully supportive of President Trump’s decision to significantly reduce the size of the national monument.

When Mark first got the news of Trump’s reduction—and later of the role energy development interests played in the ordeal, which was revealed in March—he wasn’t surprised.

“I immediately thought about Phil Lyman and Calvin Black,” Mark said. “But I immediately thought we gotta come together and fight this issue. And also I thought about our religion, our culture, our ceremony. Resort to that to deal with the issue.”

Within hours of Trump’s declaration to shrink the monument, UDB, the Inter-Tribal Coalition and several supporting organizations, which had prepared for the possibility, filed federal lawsuits to contest it. They’re still pending a hearing date, but Mark requested an opportunity to speak in court.

“I thought about all the sacred places, ancient sites, traditional sites,” Mark said. “If I’m called to testify or speak to the issues in court, I felt like I had the experience to do that. And that would not be lying, because I walked the land, and I lived there.”