A journey to Mt. Shasta City, the New Age capital of California, where ancient enlightened beings dwell in underground cities and humans squabble over who truly represents them.

I was right around Whiskeytown at the edge of the forest when I got my first glimpse of Mount Shasta. I was driving on highway 299 about to join the I-5 North at Redding, CA, 70 miles and more than an hour away from the mountain’s foothills. This 14,162ft cone of an extinct volcano is half the size of Everest, and because it stands alone, it looks more like Mt. Fuji. It’s not foreboding like Himalayan mountains, and it doesn’t loom with a stern, steep face like the Eiger. There’s something about its gradual slopes that gives it an accessible, intimate feel. That intimacy, perhaps, explains why so many here feel like Shasta is more than a mountain, that it almost has a personality of its own, that actively calls them to live and worship in its shadow.

Mount Shasta is a center of mystical, paranormal and metaphysical activity like no other in America. The mountain was worshipped for millennia by the Wintu and Hopi and other Native American tribes, but over the last century and change, they have been joined by believers in aliens, UFOs, Bigfoot, and lizard-people.

Mount Shasta’s weather system forms lens-shaped clouds around the dome that look uncannily like flying saucers, clouds that believers says are meant to hide the alien mothership. But there are also more traditional spiritual seekers here. Mount Shasta City, a town of only 3,300, supports a Buddhist monastery and over 20 centers of worship, from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints to the Abundant Life Church of the Nazarene.

It has also inspired writers. The Shangri-La in James Hilton’s Lost Horizons, though set in the Himalayas, was inspired by Mount Shasta. Bram Stoker wrote The Shoulder of Shasta, a romance set on the slope of the “old volcano”, two years before Dracula came out. Jim Morrison crowned himself the Lizard King because his girlfriend, who grew up in the shadow of Mount Shasta, told him about the Reptilians who supposedly live in the mountain.

But no myth is as striking to me as the story of the Lemurians. Living deep inside the mountain, they are the descendants of refugees from the sunken continent of Lemuria, who left their ancient civilization to take refuge in the mountain after a cataclysmic event 12,000 years ago. If the mountain calls some to move here, it was the Lemurians, or at least those who believe in them, who made me want to visit.

Mount Shasta is visible from most points in the towns in its foothills—but after my first glimpse, for most of my stay in Mount Shasta City, clouds of the non-Lenticular variety obscure it. It’s like being at a party where the host is always in a different room, but there are portraits of them all over the place.

Mount Shasta City clings to the mountain’s foothills nine miles from its peak, a few clustered blocks around the L-shaped Mount Shasta Boulevard. The town is a small clearing in miles of black forest; it could be in the Alps, but for the dry, red tint to the soil and the manzanitas. Siskiyou County is not the California of Prius and Tesla; this is Big Truck country. Except there are more crystal stores than bars, and townspeople divide the town into rednecks and “purplenecks” (the color purple is revered by one of the new age groups in town). I get no cell phone signal with my carrier, and have to resort to actual printed maps to get around for the first time in a decade.

My first morning in Mount Shasta, a misty Sunday, it seems deserted. (I guess they must be at their 20-plus places of worship.) But I first pick up the Lemurian trail at the Mount Shasta Brewery, six miles up I-5 in Weed.

On the menu, along with Shastafarian Porter and Weed Ale, there is a Lemurian Golden Lager. The head brewer keeps a Lemurian Quartz crystal near the vats. And it turns out one of the brewery employees, Charlotte Kalayjin, a 23 -year-old native of Weed, CA, has a Lemurian story.

“I was with my dad hiking on Mount Shasta. I was about 12, and I don’t remember which route. But I remember it was summer because there was no snow. Something just appeared in front of us—and it was grey, small and round.”

It disappeared a few seconds later, without having said a word. She alternately describes it as an alien and a Lemurian—the two are often conflated, though Mount Shasta Lemurians are thought to be the descendants of an ancient, advanced, earth-bound race, and are generally reported to be not small and grey but tall, with white hair and flowing robes.

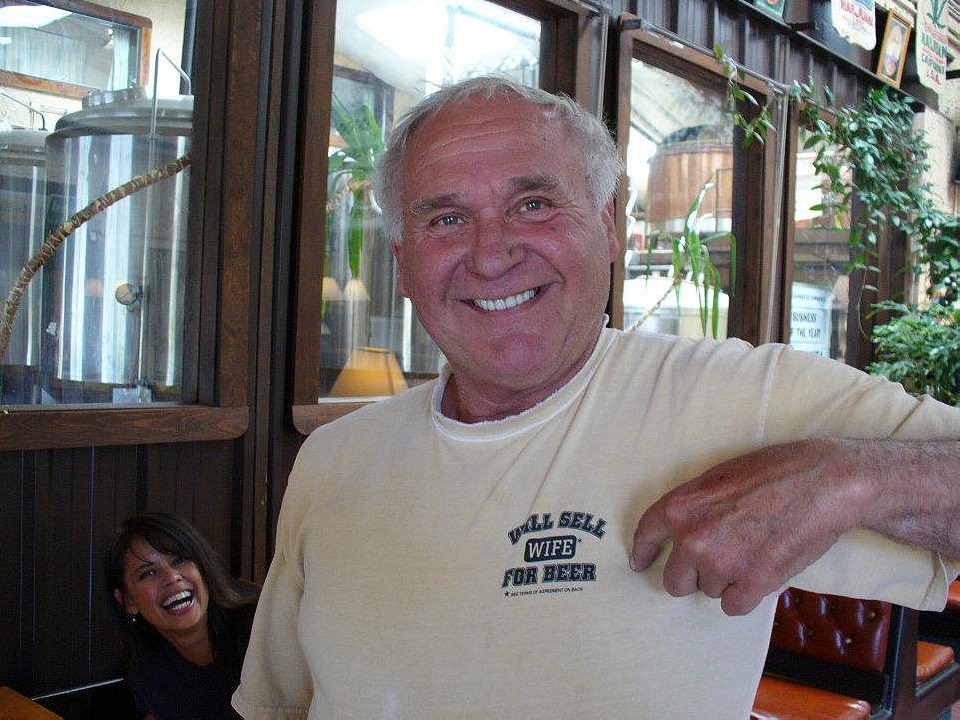

Charlotte’s boss, Vaune Dillmann is a gregarious, grey-haired Milwaukee-born cop with large features who relocated here from Oakland. (In 2008, Dillmann got a some nationwide notoriety or as he puts it, free advertising, when his “Try Legal Weed,’ beer marketing campaign got him in trouble with federal regulators.)

“A lot of strange things happen here—you wouldn’t even be able to make them up,” says Dillmann. His office is dark, but illuminated by one picture window—the snow of Mount Shasta is just visible from behind Black Butte, a bizarre structure that looks like a gravelly pyramid but is actually a pile of lava domes. He says he once had a man in his office who claimed to be a “slider”—someone who causes electrical systems to short. At one point, the slider spread out his arms, but didn’t touch anything. Dillmann shows me a couple of beer cans on the shelf. They are empty, and look slightly bent. “When he spread his arms out, those exploded open. Beer went all over my ceiling, my paperwork, everything.”

Dillmann’s office and brewery is stuffed with souvenirs of his life, from bottle caps to grand pianos made for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, and twice as many stories to go with them. He says he has never seen one himself, but Lemurians are iconic enough in Shasta to warrant their own beer.

In November 2004, Dillmann ran a contest to design the label of his Lemurian Golden Lager, encouraging locals who had seen Lemurians to send in their artist’s impressions and descriptions: “We had the body, but we needed a face,” he says.

He asks me to take a fat zipped-up folder down from the shelf, from which he takes out a thick sheaf of papers. These are the responses to his call-out, about 80 entries for the label, with renderings of Lemurians varying from comic to intricate. There are also accounts of encounters, entire histories, and other strange reflections about the mountain. One described encountering a tiny man next to the basement of his house, who shrunk him down to 12 inches and showed him around the tunnels of an underground city (this city, Telos, is central to Lemurian lore).

Dillmann framed his favourite one, and it sits on his shelf. The contest won him some local fame, but also ruffled some feathers.

“It was 6pm, I was finishing up for the day, and through the window I saw this bright pink-purple Mercedes pull up in the parking lot. I thought it was a door-to-door saleswoman or something. Out comes this older lady with a beehive so big, it swayed as she walked. She was really angry. She wagged her finger in my face and started barking at me: how dare I demean ‘our people’. ‘We don’t even drink!’ She even insinuated she would take me to court.”

This beehive and pink Benz did not belong to a Lemurian, but to Aurelia Louise Jones, a native Quebecer who moved to Mount Shasta in the ‘90s and called herself the human representative of the Lemurian race.

Dillmann managed to talk Jones down, explaining that his was a family business and that he was in tune with the community. Jones was won over and by the end of the encounter, she gave him copies of her books and inscribed them, “To my dear friend, Vaune.”

“After that, we were golden.”

The idea of Lemurians has a complex pedigree—rooted in science, pseudoscience, science fiction and various esoteric beliefs.

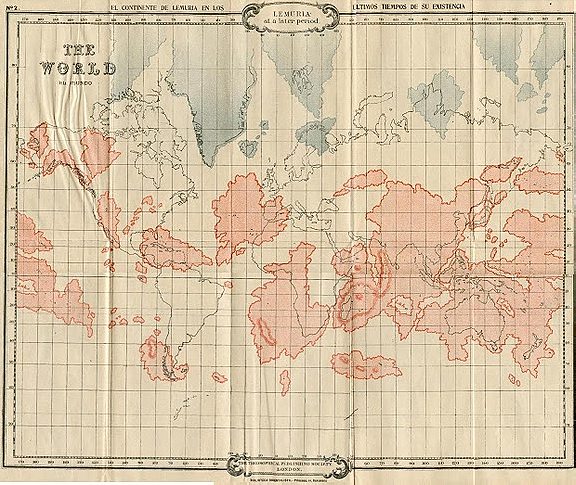

In the 18th century, a palaeontologist named J. Sclater came up with Lemuria—a theoretical land bridge—to explain how Lemurs got from Asia to Madagascar. Plate tectonics pretty much ended the vogue for lost continents in science, but Lemuria was co-opted into a popular theory of a lost, pre-Atlantean continent called Mu that explains common mythology and symbology between disparate cultures. The concept evolved in different directions, but in certain circles of thought Lemuria-Mu morphed to incorporate much of the Pacific, and eventually, California and the entire West Coast of the U.S. A great flood, or thermonuclear war, depending on who is doing the telling, caused the Lemurians to take refuge in Mount Shasta.

Their descendants still live there, although according to Lemuria believers, they are not inside the mountain on earth’s physical space: they exist in a fifth dimension, but they can travel freely back and forth between that dimension and ours.

The Theosophists took up Lemuria in the 1880s. In her writings, Theosophical Society founder Madame Blavatsky furnished the Lemurians with the metaphysical properties they still have today. To her, they were not just ancient refugees; they were a spiritually advanced civilization. Blavatsky’s writings were influential, an appealing mix of ancient religious ideas and new concepts borrowed from Darwin and modern science, but Lemuria was not linked to Mount Shasta until the publication of Frederick Spencer Oliver’s A Dweller on Two Planets in 1904. Oliver—who grew up in the gold rush town of Yreka not far from Mount Shasta—claimed his writing was channelled through visions and “mental dictation” from Phylos the Tibetan, of the Great White Brotherhood, who once lived on the ancient continent of Lemuria but now lived in the depths of Mount Shasta. The book incorporates many Theosophical ideas.

But the most decisive chapter for Lemurians came in 1931 when Harvey Spencer Lewis, a founder of the San-Jose-based Order of the Rosicrucians, published under the pseudonym Wishar Cerve, Lemuria: The Lost Continent of the Pacific. It tied various strands of Lemurian lore together by rehashing other books and articles, cementing the link between Lemuria’s ancient civilization and archaeological ruins in the western United States, and trying to support his claim that Lemurians were a common ancestor to all mankind. The book draws heavily on Dweller on Two Planets and Blavatsky’s writings, with some added shopkeeper testimony about tall, slender men in robes who paid in gold nuggets. But it goes a step further in asserting that Lemuria and Mu are the same thing.

What truly ensured its impact was the claim that the descendants of the Lemurian Garden of Eden were to be found in California, not Asia or Africa; and, just as curiously, that California was the oldest territory on earth. The notion that California was the true cradle of mankind was impossible for Golden Staters (narcissists even then!) to resist. California was already a haven for new religions and thought; this new belief in Californian Lemurians just added to the mosaic.

In the 1930s, the spiritual influx began in earnest—thanks both to Cerve’s book and the I AM movement, which was founded in the wake of a 1934 book, Unveiled Mysteries, which was written by a Midwestern mining engineer named Guy Ballard.

Ballard was a fan of Theosophist ideas, and he claimed in his book that while on a hike on Shasta in 1930, he met Saint Germain, a common figure in New Age beliefs who is alleged to be an 18th century alchemist, referred to by followers as “the Wonderman of Europe” and “the man who knows everything and never dies”. St. Germain called himself an Ascended Master and began training Ballard to be a “messenger”. Based on these teachings, Ballard and his wife founded the St. Germain Foundation— a group (classified as a cult by J. Gordon Melton in his Encyclopaedic Handbook of Cults in America) that is still active today. It remains guided by “I AM” activity—the acronym comes from Ascended Masters and the religion includes a series of affirmations such as “I AM the spirit”. (The I AM concept had already appeared in A Dweller on Two Planets). The idea of Ascended Masters (St. Germain is one, Jesus is another) like the Theosophy that influences it, blends Christianity, Buddhism, and other spiritual threads. It is essentially a guide to life based on Ascension–achieving an individual higher spiritual consciousness.

Ballard also described the visions of his and St. Germain’s past lives in Atlantis and Lemuria when he was at Mount Shasta—and soon, the mountain was besieged by Lemuria seekers—many of whom were I AM followers.

The St. Germain Foundation bought a lot of land around Mount Shasta. Not everyone was thrilled with the area’s spiritual makeover. When the foundation bought the historic Shasta Springs Resort in the 1950s, in Dunsmuir, it made what had been beloved public land, including two waterfalls, off-limits to the locals.

Frank Barr was seven years old when he came to Dunsmuir in 1949, when his father got work at a lumber mill. Sipping on barley wine at Dunsmuir Brew House in a pair of denim Dickies overalls, he had plenty of complaints: “They took away our free country! Bought up the retreat, painted it white, and put up No Trespassing signs. They don’t contribute anything to the community.”

People said you don’t have to go to India, just go to Mount Shasta

Today, many I AM adherents live at the Dunsmuir complex. There is an I AM Reading Room and a temple in Mount Shasta—and a yearly ‘I AM COME’ pageant. I AM adherents revere the color purple; the Violet Ray is divine love. (Before I visited the Reading Room, Barr told me not to wear red or black.).

Another influx—not just of I AM followers—began in the 1960s, with the cultural appetite for spiritual alternatives and expanding consciousness: “A lot of people were travelling to India,” says a spiritual guide and coach named Andrew Oser. “But people said you don’t have to go to India, just go to Mount Shasta.”

Aurelia-Louie Jones was a public face for Lemuria-Telos, and gave it a global footprint; her books were translated into 17 languages and there is a worldwide Telos network that is still active. Jones died of cancer in 2009.

But Jones was not the first to channel from Telos: that was Diane Robbins, a schoolteacher from Rochester, NY.

Robbins lives in a dark-wood house at the base of Mount Shasta; one more left turn, and you are on the road that takes you up and into the mountain’s dense forest.

In 1990, Adama, the High Priest of Telos, contacted Robbins telepathically and began to dictate. “I didn’t even question why—I just did it. I took messages for 2 or 3 years, word for word.”

When finally, sitting in her kitchen in Rochester, she asked Adama what to do next, he told her to bind and market the book, which she did. Telos: Original Transmissions from the Subterranean City beneath Mount Shasta was published in 1992. The current edition features a blurb by Shirley MacLaine: “I read this book and found it to be fascinating.”

Telos, she explains to me, means “communicating with the spirit”.The book’s purpose was for others to make their own connections with Adama and to attain higher consciousness. In this iteration, Adama is an Ascended Master in the tradition of the I AM movement. The book reveals details of Telos’ advanced society, such as the Telosian Justice System; it also says Lemuria ended not in a flood, but thermonuclear war.

In Robbins’ reading, Telos is one of 100 subterranean cities inside the earth called the Agarthan Network – the book also contains a diagram of the Hollow Earth. The Hollow Earth theory has waxed and waned for centuries, but is present in many ‘alternative history’ beliefs and conspiracy theories, including the Illuminati. It appeared in in two of Blavatsky’s books, and she may have cribbed it from the holy city underground found in some Buddhist ideas.

Robbins insists that she does not read about other people’s experiences with Lemuria or Telos. “I could never read them; I don’t want to hear about them, otherwise I don’t know what’s coming from me, or from the Ascended Masters. I never even watch movies, because I have to be clear. I can’t do what I do if I fill my mind with other people’s information.”

Robbins says she had however, listened to the revelations of Sharula Dux – a supposed Princess of Telos inside Mount Shasta, born in 1725, who said she came to the surface through Mount Shasta’s tunnel systems in 1988. Sharula Dux spoke at conferences and gave a few interviews, revealing that Atlantis and Lemuria were two great continents that fought a war; that Telos is an underground city in the Agarthan Network governed by 12 Ascended Masters, with Adama its high priest. These revelations are the root of the modern channelers, it seems.

It appears that Dux, also known as Bonnie Condey, ended up in Santa Fe with her husband. (Santa Fe is also a St. Germain hub—and was also, in some books, the location of Telos.) According to an investigative journalist in Austin, TX, Sharula/Bonnie was born in Utah in 1952 and worked as a stripper in Hollywood under the name Atlantis. The name Sharula had also appeared in a 1978 Romance novel.

A few months after Robbins’ book came out, Aurelia Louise Jones contacted Robbins and offered to help publish and promote a second edition. Jones then moved to Mount Shasta in 1997, and started channelling for her own messages from Adama and Telos.

Robbins and Jones worked together for a time: Jones was in the dedications in Robbins’ second and third editions. But they differed in their approaches, particularly on the correct way to channel Adama: “I wrote down word-for-word what Adama said to me, and Aurelia wanted me to edit my sentences, so we would argue.”

Robbins explains that Jones performed what she called a “co-creative process” in her books by editing Adama’s channelings, which Robbins believes diluted and disrupted Adama’s true “vibration”.

Even a spiritual mecca is not immune to small-town politics.

At Adama’s insistence, Robbins moved to Mount Shasta in 2007, expecting to join a welcoming community, but found that fellow Lemuria/Telos believers in Jones’ circle would have nothing to do with her.

“Aurelia [Jones] really did not want me to move here. She sent me emails telling me not to move here. She didn’t want anyone to know,” says Robbins. “And when I came here, nobody talked to me. I can only imagine what she told people about me. Her ego got in the way. And those people are not following the teachings of Telos. It’s really sad.”

Robbins is not sure what to make of the alleged encounters around the mountain; “People tell me all the time they’ve seen Lemurians… but Adama made it clear that they weren’t showing themselves right now.”

For her part, Jones claimed to have encountered Telosians only once; two tall gentlemen showed up at her door and bought $400 worth of her health products. She had complained to Adama about cash flow problems. She suspected the men were from Telos, not Tahoe as they said, but one of the rules is that Telosians, while they surface from time to time, cannot reveal they are from there. Although Adama did confirm to her afterwards that he had sent them.

Ashalyn, who runs Shasta Vortex Adventures, says she is not an adherent of any of the movements in Mount Shasta. When I ask he if she has had a Lemurian encounter, she responds, “I don’t see Lemurians, I channel them.” She is currently working on her own book with Adama. Her previous book was written with Thoth the Atlantean, another Mount Shasta inhabitant.

There are other spiritual vortex locations, such as Arizona’s Sedona Valley, and other New Age centers like Santa Fe. But the mountain makes it easier for people to tune in to whatever they’re trying to hear.

So what are people seeing when they have encounters with odd people? Some tell me it’s more about the feeling, not seeing; many of the strangest stories contained in books from the last century seem to have been taken as second-hand gospel by others.

Saranam (birth name: Mark Greenberg), who works at Mount Shasta’s Crystal Room, has another theory: people who have meditated a lot and have themselves tapped in to a higher consciousness might seem otherworldly to others who hike on the mountain. “People might just go there and meet people there that have a presence – and think they’ve had an encounter with a mystical being.”

Mount Shasta was settled in the 1820s, and became a busy stop en route to Yreka during the Gold Rush. From the early 1900s came Italian immigrants. Many also visited for the pure spring water; there are still ruins of an old sanatorium where tuberculosis sufferers would recuperate, which is now being reclaimed by the forest.

But then the sanatorium business died off, and lumber and other extractive industries sank. The region is still economically depressed. Jim Mullins, CEO of the Mount Shasta Chamber of Commerce, says they are working on getting more tourists to come, hopefully by advertising outside of the region. In any given year, between 2000-4000 visitors per month come to the Center, and the summer is the peak season for both recreational and spiritual visitors.

Lemuria believers are a loose collection of individuals, but many of them make a living doing it. Some, like Jones, are channelers – conduits between humans and the city of Telos inside Mount Shasta. The practice of contacting Lemurians draws much from Theosophy and the I AM movement, particularly the idea of spiritual hierarchy.

About one-third of Mount Shasta’s population is involved in the metaphysical

In this reading, Lemurians live in Telos, and Adama, their High Priest, is an Ascended Master who speaks through human messengers. Some lead meditation sessions with visitors; some sell books online or in the book stores around Mount Shasta; some travel the globe to speak about their experiences; another might do weekly Ascension sessions, or do the same thing on Skype. This also draws visitors interested in the subject to Mount Shasta – spiritual tourists.

Ashalyn estimates about one-third of Mount Shasta’s population is involved in the metaphysical in some way. The city’s Chamber of Commerce literature lists a couple dozen Spiritual or Alternative Health businesses – but there are many more business cards and pamphlets in restaurants advertisings similar services, plus a clairvoyant chiropractor. The mountain is a local industry; people come to hike or fish, but also for spiritual retreats, and there is a loose collection of spiritual entrepreneurs who serve this industry. “New Age” is a baggy term these days, but its original meaning—an alternative way of living in spirituality, finding God within oneself and practicing a mixture of spiritual beliefs rather than following one doctrine – is not far off from what happens here.

But for all the mountain’s broad appeal, it’s not a close-knit community.

Ashalyn says she came here in 1988 “to be a part of the metaphysical community, but when I got here I found there was none. Everyone just operated out of their own house.“

“You ever hear of the expression, Too many chiefs, not enough Indians? Well, there are a lot of chiefs in Mount Shasta.”

There’s a sort of spiritual segregation in town as well. Mount Shasta’s various spiritual groups have their own hangouts, according to Oser. The Coffee Connection is where Christians get coffee. “Spiritual, non-religious” residents linger with coffee at Seven Suns, and shop at Berryvale, the organic produce store. The rest shop at Ray’s Food Place.

Many people are drawn here, but everyone’s experience of the mountain’s energy is personal.

Something I hear frequently, is that people who live here do so at the pleasure of the mountain:

“Either the mountain accepts you, or it doesn’t,” says a friendly woman behind large framed glasses named Ann, who crafts Native American drums. She came here full-time in 2005 after dividing time in Mount Shasta and Sedona. She wanted to be closer to the vortex. “If you have baggage, the mountain amplifies it.”

“Many people who came here answer a call of some kind, but being here is too intense for some people,” says Saranam of the Crystal Room.

Andrew Oser, the spiritual guide, takes me to see some of the mountain’s sacred sites; places for contemplation, or ceremony, where the energy is especially pronounced. Oser organizes vision quests and mediation sessions for visitors. He says his clients come from all kinds of beliefs and backgrounds.

Oser is a lean, soft-spoken character in his 50s, with curly brown hair and just a hint of grey. He came to Mount Shasta full-time from San Diego in 2006, but had been coming since the 1970s. He was raised in an atheist Jewish home. A Princeton summa cum laude graduate and long-time tennis coach, he started a non-profit in D.C. called Joy of Sport, which was honored as a Point of Light by President Clinton, after the idea sparked at a meditation session at one of his favorite spots on the mountain. He has a laminated portrait, the size of a playing card, of the Archangel Michael in his car.

As we drive up the winding road towards the snow line, the temperature palpably dropping with each turn, trees covered with lichen; the green, white, and silence, is eerie.

One of the sites Oser brings me to, a short walk from a road into the trees, is a sort-of secret rock formation that is supposedly also a nexus of sacred geometry. Some report feeling high here. It is beautiful and peaceful, but for me at least, it is only that. I do feel that being at this spot alone it might be overwhelming and kind of scary; I have a healthy fear of getting lost in deep forests. Or maybe it’s the remoteness that unsettles me. Then again, maybe you need to do this kind of thing alone to tune in.

Our last stop is a headspring of the Sacramento River. Locals come here to fill up water bottles and gallons jugs; the water is known to be some of the purest known to man – or at least to the U.S. There are two signs next to it; one says to drink at your own risk; the other, that this water fell as precipitation on the mountain 50 years ago.

We mull the question of what draws people to the mountain.

“The question is to what extent people’s experiences are based on some energy here, independently of their beliefs, and to what extent it’s their expectations that form their experience,” says Oser.

We agree it’s probably a little of both.

Perhaps it’s the centuries of consecration that makes the mountain feel sacred; people could be responding to this accumulated reverence in the same way – but inverted – that some report feeling when visiting Cambodia’s Killing Fields or Gallipoli. But there too, people’s knowledge of the events informs their experience.

Nevertheless, I leave Mount Shasta 15 hours earlier than planned. I had intended to leave early Thursday morning, but on Wednesday evening as I was finishing up my notes at the Wayside Inn, I’m struck by an overwhelming urge to hit the road. Maybe the idea of driving South through the Trinity forest bathed in late-afternoon sun—and going to sleep in my own bed—is far more appealing than one more night in my cold motel room. Or maybe I’m being gently exiled. Maybe a little of both.

[Header image: Lenticular Cloud and Mt. Shasta by Brad Greenlee, used under CC BY 2.0]