Iman Muzaeva recounts what it was like to live as an ISIS wife, first in Raqqa, then in Tal Afar—and how she finally mustered up the courage to run away.

At the Tsvetochny amusement park in Grozny, Iman Muzaeva smells of perfume. She is wearing a loose dress down to the heels, and a coffee-colored hijab is wrapped around her heart-shaped face. The mascara on her eyelashes is hard to miss. On her fingers, silver rings. She’s come to the park with her sons. Muzaeva had always dreamed of bringing her sons to this park, so on this day, she buys them everything they’ve asked for—a ride on the kids’ train, balloons, chips, and a slingshot helicopter.

At her parent’s house in Goyty, a small village not far from Grozny, the capital of the Russian republic of Chechnya, she lives in a tiny room, half-empty and warm. An aluminum kettle and mantovarka, a dumpling steamer, are heating on top of a gas stove. The table is filled with food. Muzaeva cooked manti—dumplings regularly featured in Central Asian cuisines—and opened a jar of her grandmother’s adjika, a Caucasus chili paste. Muzaeva had thought about renting an apartment in Grozny because it was inconvenient to live in a place with outdoor plumbing when you have three small children, but her father insisted that they stay in the family home.

It’s been two and a half months since Muzaeva, now 25, fled ISIS in Iraq, where she’d been living with her husband and children for two years. A young woman from a tiny Chechen town, Muzaeva had followed her husband to Raqqa, the self-proclaimed ISIS capital in Syria, before they moved to the Iraqi city of Tal Afar, which had fallen to ISIS in 2014. Russian officials say more than 3,500 Russian citizens had gone to fight for ISIS in Syria and Iraq. No one knows exactly how many of them were Chechens, but some estimates say 400 to 500 men left directly from Chechnya to join ISIS.

In Tal Afar, one of the last Iraqi cities under the control of extremists, nearly 1,000 ISIS fighters were deployed to defend the city. In the weeks before the city was recaptured by Iraqi forces, Muzaeva managed to escape with a dozen other people to Kurdish-controlled territory before she was rescued by members of the Russian government. Her rescue was part of an unusual effort to bring back the families of Chechens who had been fighting for ISIS back from Syria and Iraq. By the end of 2017, at least 93 women and children had returned home after Ramzan Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, offered them a safe route home. Kadyrov, who has deployed heavy-handed tactics to quash extremists at home, has been at the forefront of the repatriation of ISIS families. It’s not merely a humanitarian impulse to help his people. It is also part of his administration’s attempt, some analysts say, to win the war on terror at home by rehabilitating the families and encouraging the returning fighters to abandon extremism.

Since returning to Chechnya, Muzaeva has been trying to erase the memories from her ordeal. She tells her relatives not to let her eldest son watch movies about war. Throughout the evening Ayub plays with his three-year-old brother, Abdurahman, and then they fall asleep on the carpet on the floor. Her youngest, eight-month-old Suleiman, is colicky and continually begging to eat. Muzaeva breastfeeds him, then gives him formula from a small bottle, and finally lays him down in a roughly hewn cradle, the same one she grew up in.

Muzaeva was born into the family of a crane operator in Chechnya. When she was nine, the family moved to Kazakhstan.

In both places, a deep cultural conservatism ruled her household. Traditions that are more rooted in the Caucasus than in Islam (her parents were not very observant) meant that Muzaeva was always subordinate to her father. She says she feared him, that she stood every time he entered a room. If he ate lunch at home, she waited until he finished, and only then sat at the table. She was never allowed to cry in front of him.

When she was 11, Muzaeva stopped wearing pants on her father’s orders. She also stopped painting her nails purple and no longer hung out with her friends. Muzaeva recalls the time when her class was going on a field trip to the movies. When she asked her father if she could join her classmates, her father planted her in front of the TV in the living room, turned off the light, and said: “Here you go, this is your movie theater.” Another time, when Muzaeva’s classmates had gathered for an outing to the shore, her father told her she can “go swimming in the bathtub.”

Muzaeva still never looks into the eyes of her father during a conversation. “Sometimes, I accidentally look at him,” Muzaeva says, “and I catch his menacing look—and then I lower my eyes. It’s is a sign of respect.”

This kind of patriarchal structure runs deep in the Caucasus, but the religion of Chechnya has become more extreme only in recent decades. Radicalism, triggered in part by the rise of Wahhabism—the dominant faith of Islam in Saudi Arabia that relies on a literal interpretation of the Quran—has been driving young Chechens to join extremist Islamist movements since the republic’s failed wars of secession in the 90’s. For centuries, the region’s dominant religion had been Sufi Islam, and the Chechen leader, with backing from the Kremlin, has been at the forefront of reviving it. In 2008, Kadyrov, in the presence of Vladimir Putin, inaugurated the Akhmad Kadyrov Mosque in Grozny, the largest in Russia. The mosque was a sign of Chechnya’s commitment to countering extremism not only through its oftentimes brutal and abusive police crackdowns, but also by encouraging Chechens to rediscover Sufism, their traditional faith.

Muzaeva says that her father was even stricter with her because they were Chechens lived in a foreign country—Kazakhstan—and he was protective of her. That’s probably why, she thought, he’d drive her to school and picked her up after the classes were over.

“I didn’t leave our home number in the school yearbook,” Muzaeva says. “I was afraid that someone would call me and my father would scold me.”

(Related: The school where Chechnya’s young boys go to study the Quran)

I thought I would marry a man like my father, a typical man of the Caucasus, who did what he said.

When she was 13 and had just finished eighth grade, Muzaeva stopped going to school. Her father decided that she should stay at home and help her raise her three younger sisters and a brother. When she turned 15, he helped her get a job at his friend’s shop, where she would work in the back of the store. That same year, her mother introduced her to a man named Suleiman, tall and green-eyed, and seven years older than her.

“I thought I would marry a man like my father, a typical man of the Caucasus, who did what he said,” Muzaeva says. “I’m used to strictness, and Suleiman had a gentle character.”

Muzaeva and Suleiman eventually became friends. They kept in touch and met with other only occasionally when Muzaeva’s father left home for his shift.

Every year, Muzaeva would return to Chechnya to visit her relatives. Her grandmother would always tell her that she should “pray, worship the Lord, and give thanks for all that we have.” She hadn’t given her grandmother’s words a lot of thought, but after she’d met Suleiman—Muzaeva agreed to identify him using his first name only—and started working with a woman who wore a hijab, they had a new meaning to her. One day, she picked up a book called “How a Muslim Woman Should Be.” Shortly after, she began wearing a hijab.

Suleiman was delighted with Muzaeva’s decision, but her parents, who did not even pray, insisted that she take off the hijab. “This is how Wahhabis look,” her father would tell her. “You look like a sack,” her mother said. Muzaeva did not want to fight with her parents so she would leave the house with a scarf tied on the back of her neck, in the Chechen style. She’d then stop at the stairs down the road, pull out her hijab, and then headed to work. It was the first time she had defied her family.

When the shop owner began noticing Muzaeva wearing the hijab, he told her that he did not want any problems with the security services, and fired her. The Kazakh security services, like the Chechen, was aggressively trying to root out Wahhabism, and used profiling—of Islamic clothing, of beards—to identify potential extremists. Muzaeva applied for a job at another children’s clothing store, but as soon as the owner saw her hijab, their conversation ended.

At some point after Muzaeva began wearing a hijab, Suleiman got more serious about his intentions toward her. He thought it didn’t make sense for him to continue meeting other girls. His mother only had good things to say about Muzaeva’s family. So, one day he asked her if they should start dating.

Muzaeva had been hanging out with Suleiman for a few years now, and although she didn’t love him, she felt he would respect her. “For the sake of observing Islam by the rules, I was ready to live without love,” Muzaeva recalls.

Muzaeva and Suleiman got married in Aktau, the Kazakh city on the eastern bank of the Caspian Sea. After the wedding, they moved in with Suleiman’s parents, who lived in the same city. Later that year, Muzaeva gave birth to their son—they named him Ayub. Unlike her father, Suleiman would take her to the movies. When they spoke to each other, they called one another by their nickname: Dogi—the Chechen word for “heart.”

“He never lied to me, not even about little things,” Muzaeva says. “We could talk all night, until the morning prayer.”

Once Suleiman started traveling for his business trips, he began immersing himself in Islam. He brought home religious books and began to read the hadith to Muzaeva. He grew a beard, started tucking in his trousers, and started spending more time talking with people online. Muzaeva was worried he was having an affair, but Suleiman told her he was talking with his “brothers,” as devout Muslim men would call each other, and she that she had no reason to worry. In the months that followed, Suleiman told her to stop listening to Chechen music. He even told her that television was corrupting her, so she stopped watching TV shows.

By 2014, authorities in Central Asian nations, including Kazakhstan, were gradually taking more and more draconian measures to fight violent extremism. Some, like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, banned beards and outlawed Islamic clothes. When his management at work asked Suleiman to shave his beard, he refused. As a result, he lost his job, making his parents very unhappy. His mother was angry that Suleiman couldn’t pay the loan he’d taken for his apartment anymore, and she blamed Muzaeva for everything.

At some point, Muzaeva began to notice a car with tinted windows that stopped in front of her house. Suleiman would get in the car and leave. One day when he returned, Suleiman told her that it was the KNB, the special services of Kazakhstan, who had been insisting that he inform them about other Muslim men whom he’d been meeting with frequently. He said he refused.

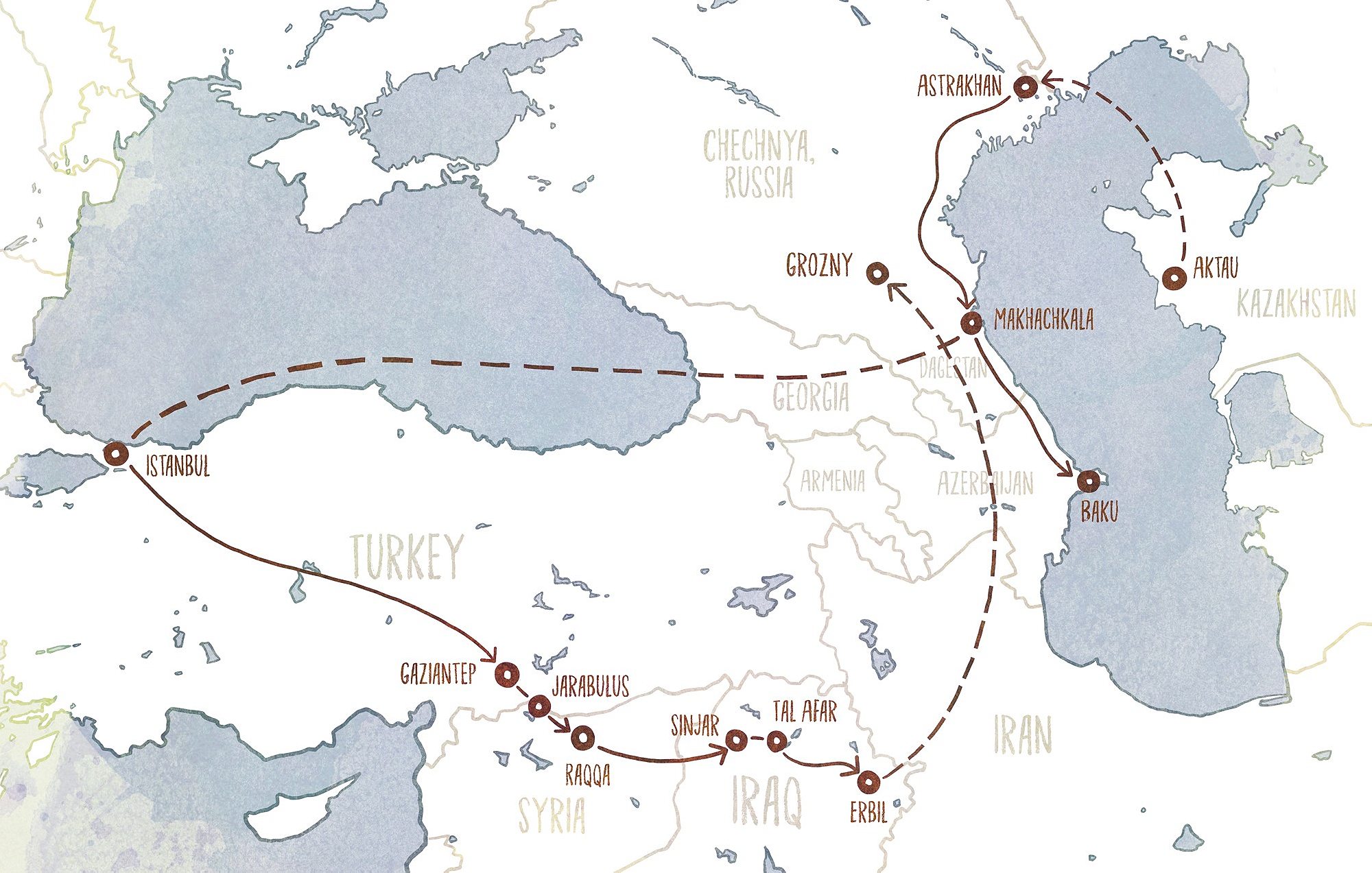

In 2014, Muzaeva became pregnant with her second child. Suleiman was still having a hard time finding a job and his family had been complaining about having to support him. That’s when Muzaeva suggested they should move to Grozny, get the child support that Russian authorities would pay for those who had more than one child, and try to build their own home. Suleiman agreed, and they decided to fly to Astrakhan, a city on the banks of the Volga in southern Russia, and then take a train from there to Grozny.

As soon as she got on the train, Muzaeva saw the Chechen conductors and felt relieved—soon they would be home at her grandmother’s for dumplings. A few minutes later, Suleiman told Muzaeva they need to move to another car on the train. Muzaeva didn’t understand at first, but soon realized he had moved them to a section of the train that’d stop in Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan, some 90 miles from Grozny. She protested. They didn’t have a single relative in Dagestan. “All the better,” Suleiman told her.

After they reached Makhachkala, Suleiman left Muzaeva and went to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, for two days. First, he told her she shouldn’t tell her mother where they were. Then he confiscated her phone.

A few days later, Suleiman showed Muzaeva a passport with their son’s information in it. He had traveled to Kazakh consulate in Baku so Ayub could travel with them. The three of them then flew to Turkey. “Now we will live here,” Suleiman told Muzaeva. “I will find a job, the brothers will help us.”

Once in Istanbul, Muzaeva, together with Suleiman and their son, got a room with another couple, separated by a thick curtain. He would leave home in the morning and return in the evening—no one knew where he’d been all day. He gave Muzaeva her phone back but told her she’d have to tell her parents they are in Poland. They were running out of money, down to the last hundred dollars, and Muzaeva was six months pregnant.

Then Suleiman told Muzaeva he had a confession to make. “We are going to Syria,” he told her. “The Islamic State is there. We can live according to Sharia, and no one will oppress us. I’ve been told that they will give us a house there, that they pay monthly salaries. We will live a comfortable life.”

It took a while for Suleiman to convince Muzaeva. He told her that the “brothers” were already there and they were content. He pulled out hadiths—teachings of Prophet Muhammad—she had never heard of before to back up his arguments. “It is the duty of every righteous Muslim to live in an Islamic State,” he told her. “To abandon the Islamic State was like abandoning prayer. It is a sin.” Muzaeva was shaking with fear. She had seen war as a child in Chechnya, and she never wanted to live under bombing again.

When Suleiman ran out of arguments, he threatened to take their son and leave her. “I don’t want my son to grow up among debauchery,” he told her. She gave in.

(Related: Welcome to the ISIS gift shop in Istanbul)

Muzaeva ran through the cornfields as fast as she could, holding her pregnant belly with one hand and pressing one-year-old Ayub against her chest with the other. It was dark, and all she could hear were men shouting from behind her to run faster. Together with 19 women and children, she was being smuggled across the Turkish-Syrian border. When they arrived at the border, the men behind them asked them to stop.

“The men shouted something at me in Arabic, pointing to my face. It turned out I was not properly dressed,” Muzaeva remembers. Another woman in the group handed her a black veil so she could cover herself from her head to feet. It was over 120 degrees outside. “I told them it was hard for me to breathe inside, but no one listened.”

In August 2014, Muzaeva and her children were brought to the Syrian city of Raqqa, ISIS’ self-proclaimed capital of their caliphate. They were left in a kind of all-female hostel called a Makar. Near the entrance of the building, on the tiled steps, there were two exhausted Yazidi women—they had been captured by ISIS and brought to Raqqa. The Yazidis, who are among Iraq’s oldest minorities and were concentrated in and around the city of Sinjar in northern Iraq, were forced to flee their homes after a vicious campaign by ISIS.

Suleiman arrived in Raqqa two weeks after Muzaeva and said that the family would move to Iraq. ISIS had been expanding its influence across the Syria and Iraq by this time, seizing territories and declaring them part of the caliphate. In August and September of that year, they posted live videos online showing the beheading of two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and British aid worker David Haines. Western officials, for the first time, announced that the number of ISIS fighters, aided by foreigners flocking to Iraq and Syria, was more than three times the number they had estimated. For newcomers in Raqqa, like Suleiman, ISIS had promised that by September, the group would take over Baghdad and celebrate Eid al-Adha—the holiday of feast and sacrifice—in the Iraqi capital.

The next day, women and men were loaded in different buses as they left Raqqa. Hours later, the convoy suddenly came to a halt. All the lights were turned off. They had arrived in the Iraqi town of Sinjar, which had been overrun by ISIS two weeks prior. Tens of thousands of Yazidis had fled the city for Dohuk, in Iraqi Kurdistan to the north, and to Erbil, while thousands of those who stayed behind were executed by ISIS fighters for not converting to Islam. More than 3,000 Yazidis were estimated killed in days following the attack, while nearly 6,000 women and girls were believed to have been kidnapped and held as slaves. Investigators would later find multiple mass graves, one of them with the hundreds of bodies of Yazidi women and children—many buried alive. This was the aftermath Muzaeva was unwittingly entering with her children.

“We stood in complete darkness and silence,” Muzaeva recalls, describing the journey on the bus to Sinjar. “I looked at what looked like colorful lights through the window. At first, I thought it was fireworks, but after a while, as the bus jerked, I realized we were being shot at.” People jumped off the bus and started running inside empty homes nearby. Suleiman grabbed Muzaeva and Ayub, rushed them inside one of the houses and threw mattresses in front of the windows to protect them from shrapnel. The three of them spent the night there as drones circled above them.

As they hid inside the house, Muzaeva could hear the whistling sound of shells falling. She remembered the war in Chechnya—and it sent shivers through her body.

Even during the height of the war in Chechnya, Muzaeva had never seen such intense bombing. Each time the shells dropped, she hugged Ayub tighter and pulled herself closer to Suleiman. “He tried to distract me by telling me about how planes work,” Muzaeva says. “We were bombed until five in the morning.” Shortly after the bombing stopped, two men came running into the house and asked Suleiman if Muzaeva could help bury women.

“I fainted,” says Muzaeva. “Many women and children were killed that night.”

The next morning, they got back on the bus. When they arrived in Tal Afar, little over 30 miles from Sinjar, Muzaeva and the children once again settled in a Makar. The men went to look for houses for their families. Thousands of residents had fled their homes fearing ISIS’s arrival—so the men picked a place they liked. Suleiman told Muzaeva they’d also found their new home. You just need to wash the floor, he told her, before they move in.

It was a modern house, with clap-activated lights, but Muzaeva didn’t want to live there. She sat on the porch and cried. Her relationship with Suleiman had suffered since they’d left Istanbul. “I did not want to talk to him,” she says, “I just kept asking to go home.” For the first time in their marriage, he raised his voice to Muzaeva. “He said that there was no road back, that we would have to live here.”

“I married without love, but then I fell in love with Suleiman.”

Suleiman wrote “Abu Ayub”—Father of Ayub—on the fence of their new home. Under ISIS rules, no one was allowed to use their real name. They instead adopted names of their eldest sons—Father of Ayub and Mother of Ayub in their case. If you didn’t have a son, you would choose a temporary name until you had a child. Inside their home, Muzaeva and Suleiman, despite their disagreements, still called each other “heart.” Muzaeva painted the white walls inside their home with hearts and flowers, and wrote notes, with a colored felt-tip pen, about how much she loves and misses him. She quoted lines from Chechen songs: Do not go, my dear, wait, my heart is only with you.

“I married without love,” says Muzaeva, “but then I fell in love with Suleiman.” He was, she says, a man of his word. He brought her long red roses when he returned from work—he was assigned as a guard at the outposts—and decorated the bedroom with scented candles. He even managed to find her favorite candy bar: Bounty. He never yelled at her or beat her. When she was ill with fever, he sat on the bed and pressed a cool cloth on her forehead. Other husbands would refuse to take their wives to the bazaar, but he did. “His only condition,” she says, “was that I wear gloves: no one should see my hands.”

Before Suleiman would return home from work, Muzaeva put her hair in curlers, put on her most beautiful dress, and always cooked something new: blinis with jam, roast chicken. They’d eat and then Suleiman would build a pyramid out of the mattresses and toss his son on top. Ayub, rolling down, would burst into laughter.

That’s what it was like in the beginning—peaceful. The drones circled overhead, but bombs never fell. After they had their second child, Suleiman worked for two hours a day and spent the rest of the time with the family. He wasn’t chosen to join other fighters on missions because of poor vision. Each month, the family got free groceries, mostly vegetables, and a stipend—one hundred dollars for each member, plus an additional hundred dollars to the father—for work.

At night, if there was a light breeze, Muzaeva would head up to the roof, climb under the mosquito net, and fall asleep. There were huge tanks of water, heated by the sun. Throughout the summer, she only had hot water to drink. In the winter, she had to bathe in cold water. Because of power outages, there was no light for half of each month. The last six months had been entirely dark in Tal Afar. Muzaeva remembered how in Chechnya when the family didn’t have a refrigerator, her grandmother cooled water. She started doing the same: she poured the hot water into a bottle, wrapped it in a thick cloth moistened with water and hung it on a tree branch in the shade. The breeze helped cool the water if only a little.

“I had an ordinary life, like in Kazakhstan,” says Muzaeva. “But I could not leave the house without my husband.” She had to climb onto the roof carefully so that other men couldn’t catch sight of her. When her son went out to play on the street, she stood in the doorway and watched him.

Once a week, husbands in Tal Afar took their wives to an internet cafe. It was a shed with sofas, but no windows. There was a woman there who monitored everything the women did online. After finishing at the internet café, the women had to leave their phones there for three days, unlocked, so that they could be thoroughly inspected. “We were afraid to write to our parents that we weren’t doing well,” Muzaeva says, “because we thought they had software to restore deleted messages.”

By November 2015, conditions in Tal Afar had deteriorated. ISIS was slowing losing ground across Iraq and Syria. Kurdish forces had retaken Sinjar, clearing the militants out from the town and cutting access to the road that connected them to Raqqa—a position they’d controlled for more than a year. That’s when the stores began running out of supplies, and fuel was restricted.

“The hardest thing is when children ask for food, but you have nothing to offer but bread,” says Muzaeva. “When Ayub cried because he wanted chewing gum, all I could tell him was to ask Allah for it.”

As Kurdish forces drew closer, Suleiman was gone from home for more extended periods of time. He would return for two days and then went away for two weeks. He assured Muzaeva that he was just being sent to guard nearby posts and that he was safe.

(Related: Sinjar has been recaptured, but it’s long way from back to normal)

One day when Ayub was playing with his younger brother, he sat on his brother’s back and made a throat-slashing gesture. Muzaeva was frightened at first. He must have seen that somewhere, she thought. She often saw boys who were barely teenagers sitting on the streets and watching gruesome videos on their phones. Muzaeva would also hear other women making comments about new videos floating around.

There’s a new execution video, we need to watch it.

You have to see the part where the brain spills onto the asphalt.

He was slaughtered like a lamb, you’ll see.

Other women showed these videos to their children. “Let them get used it, they are going to be soldiers,” Muzaeva recalls one of her neighbors telling her. But unlike other mothers, she thought this would damage her children’s minds.

Muzaeva had never been to a public execution. But Suleiman had. He would come home and tell her all about it. One day he told her about how a woman confessed to adultery with a married man. She was stoned to death in the square, where women were among the spectators. No one was forced to attend, but ISIS encouraged the residents to watch executions so they would know what would happen to them if they violated sharia.

Suleiman told Muzaeva about another woman who had been accused of placing microchips in homes, schools, and mosques so the Iraqi troops could know where to drop their bombs. During the execution, ISIS fighters asked a woman of similar age to step forward from the crowd, handed her the gun, and made her shoot the woman.

Suleiman told Muzaeva how the women who wanted to escape from ISIS were put in prison and raped, and the men who tried to help them had their heads cut off. When one of Muzaeva’s Russian friends told her husband that she wanted to go home, he threatened to turn her into authorities. That’s when Muzaeva began hearing rumors: for $6,000, you could hire a car that would take you across the border. But she didn’t know anyone who could confirm it, and it was terrifying to even show any interest in it.

Do not let yourself be deceived by Satan, our relations are better here; if something happens to me, I want you to live here.

One day Suleiman found Muzaeva’s passport that she had hidden in a cupboard, behind the dishes. “Do you still want to leave?” he asked her, before going out to the yard and setting fire to her passport.

“I loved Suleiman too much to betray him,” says Muzaeva. When he left for the guardpost, he would leave her notes: “Do not let yourself be deceived by Satan, our relations are better here; if something happens to me, I want you to live here.”

When Suleiman returned home from his latest two-week deployment, he looked glum. “Don’t panic, but I have to tell you something,” he told Muzaeva. “I’m leaving for Ramadi.” It was the winter of 2015, and ISIS had deployed between 600 to 1,000 fighters in Ramadi, less than 60 miles from Baghdad. Hundreds of them had been killed in fighting and airstrikes since the final phase of the offensive began in December. Muzaeva knew that practically no one came back from there. If forty men left for the battle, only two returned home.

Muzaeva sat in a chair for several hours and couldn’t think of anything coherent to say. She then told Suleiman she was pregnant with her third child. Muzaeva could not stop worrying because Suleiman himself didn’t seem happy about leaving this time. She’d never seen him like this before—pensive and reserved. She begged him not to go.

“I have to tell you that I have never fought for these lands, for this caliph,” Suleiman told her. “I have always fought for Allah so that my family can live according to sharia.”

The next morning at dawn, he left home.

Two weeks later, a woman knocked on Muzaeva’s door. Suleiman had been killed, she told her. Muzaeva did not believe the news at first. But when the surviving ISIS fighters handed her a letter from Suleiman, she knew it was true.

After a seven-month occupation, ISIS had lost Ramadi—as well as 40 percent of the territory in Iraq it had captured the previous year.

It was an eight-page letter, in which Suleiman described all the beautiful moments they had spent together. He wrote that he was the happiest husband and that he never imagined Muzaeva could love him as much as she did. He urged her to continue to look after the children and to ask for perseverance and patience with God. He said that he did not want to leave his family behind, but that he had to do it for Allah. But he didn’t write anything about what she should do next, or if they should continue to live among ISIS.

Four months after his death, Muzaeva gave birth to their third child, whom she named after the father. After his death, Muzaeva and her children were classified as a shahid—martyr—family. When ISIS administrators distributed free rice, shahid families came first. If the family ran out of firewood, they would have someone bring them wood. Nobody refused them.

When she was done with her mourning, Muzaeva said matchmakers, including Suleiman’s friends, started knocking on her door “eight times a day.” Even some wives came, says Muzaeva, to recruit her as a second wife. They wanted a Chechen. One neighbor came to set Muzaeva up with her son, demanding to know what right Muzaeva had to refuse because her children needed a father.

“Today he marries me, and tomorrow, he will go and die,” Muzaeva told them. “All of these fairy tales—that they marry to look after the orphans—I do not believe them. They just want to satisfy their desires.”

By the beginning of 2016, there were practically no men left in the village—the ones who returned from the battlefield came back without hands or feet. The streets had turned into a sea of black, women, dressed from head to feet in black robes, swept past the windows like flocks of ravens. Muzaeva knew that nobody cared about her anymore.

“We were tired of living with fear.”

From time to time, the ISIS gave its residents rice, bulgur, and tomatoes. Nothing else. Muzaeva had started giving her sons salty water from the well so that their bodies would get used to it. The Arab locals who had stayed behind warned that they would not be able to deliver food. The price of a bottle of cooking oil soared to $40, watermelon cost up to $100, and a pack of chewing gum was about seven dollars. Muzaeva’s newborn was five months old and constantly malnourished. She was losing milk because she didn’t have enough to eat for herself.

When the last canister was empty, and there was no more cooking gas, Muzaeva had to figure out how to feed her children. She took an oversized metal can that had once held ghee, carved a hole to make it into a little furnace, put a tray on top, and lit a match. At first, she threw wood into the fire, and then old egg cartons, discarded slippers, anything else that would burn.

One evening, when Muzaeva and the children climbed to the roof to lay them to sleep, a rocket whizzed overhead, and the neighboring homes folded like a house of cards. Dust and dirt flew into their eyes. Then the bombings started becoming routine, from three in the morning into the evening. Sometimes Muzaeva just barely had time to throw the children down to the floor to protect them from shrapnel.

“It came to a point when we simply did not have the strength to hide or run,” she says. “Let it fall where it will, that was our attitude. We were tired of living with fear.”

While the men were off fighting, their wives and families were looked after by men called Idar—the Idars, however, were not supposed to see the women, so Muzaeva would write shopping lists and slip them under the door with some money. The man would run the errand and leave the groceries by her front door. They were never supposed to meet.

But the Idar who looked after Muzaeva wanted to marry her.

People told Muzaeva that he had looked at her through the fence and fallen in love. He brought chocolate for the children, left bread at the doorstep and then walked away. Muzaeva decided to take advantage of his interest, so one day, she asked Ayub to give the Idar a message: she needed to get online to ask her mom for money. When the Idar gave her his phone, she wrote to Suleiman’s mother on WhatsApp: Help me, I want to get out of here, write only in Chechen. Her mother-in-law promised she would think of something.

The first time they tried to escape, they were caught by ISIS soldiers.

In the spring of 2017, her mother-in-law contacted the Russian Consul in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. When the consul called Muzaeva, she told him her story and started sending him any documents she could find. A few days later, the consul called Muzaeva again and sent her a map marked with a place where she should go to. Supervised by the Kurds, Muzaeva and her children tried to escape with three other women, a man, and ten children.

The first time they tried to escape, they were caught by ISIS soldiers but were not killed: the man who was with them convinced the soldiers they were only exploring the area. The next time they found themselves in a field laden with mines, which, it turned out, was the only way out. “It was a minefield, with a narrow path through the middle,” says Muzaeva. “I was walking sideways, holding one child in a carrier. The other two held my hand. It was terrifying. We walked for about 40 minutes.”

Once they arrived across the field, they surrendered to Iraqi Kurdish soldiers. The soldiers checked their bags and drove them to Erbil. There, the family was questioned by authorities and then put in a detention center. Muzaeva says that some of the others who were fleeing took German hairdryers from their Iraqi homes, but Muzaeva had only one set of clothes for her children in her backpack and some dates that were as hard as a stone. She ate them with her children at the detention center. Two weeks later, Ziyad Sabsabi, a Chechen official, arrived in Erbil. He worked out an agreement with the Kurds and helped speed up the paperwork.

On September 1, 2017, Muzaeva, along with three other women and eight children, flew to Grozny on a chartered flight from Erbil, sent by Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic. When she arrived home, Muzaeva was asked what the first thing she wanted to do was. She said she wanted to take her kids to the street fair. “I want to buy them sweet corn on the stick,” she said. “In Iraq, there was only salted corn.”

This story was adapted from the Russian version published in Takie Dela. Translated by Nathan Thornburgh.