“Give us his breath or his body”

In 2004, twelve men from Nepal who were tricked and hired for subcontract work on a U.S. military base were murdered by Islamic extremists. In his book “The Girl from Kathmandu,” American journalist Cam Simpson tells the shocking story of the massacre, and a widow who dedicated her life to finding justice for her husband and the other victims.

In August 2004, twelve men left their village in Nepal for jobs at a five-star luxury hotel in Amman, Jordan. They had no idea that they had actually been hired for subcontract work on an American military base in Iraq. But fate took an even darker turn when the dozen men were kidnapped and murdered by Islamic extremists. Their gruesome deaths were captured in one of the first graphic execution videos disseminated on the internet—the largest massacre of contractors during the war. Compounding the tragedy was the reality that their deaths received little notice. Why were men from a country so removed from the war, in Iraq? How had they gotten there? And who, exactly, were they working for?

The following piece is an excerpt from The Girl from Kathmandu, a book by investigative journalist Cam Simpson, who embarked on a journey in 2005 to find answers to those questions. A decade-long odyssey would uncover a web of evil spanning the globe—and trigger a chain of events involving three indefatigable human rights lawyers, a formidable multinational corporation with deep government ties, and one brave young widow, Kamala Magar, on whom the book is centered.

Rumpled and exhausted, Kamala fell onto the platform bed and wrapped herself around her eighteen-month-old daughter. Sowing rice consumed everyone’s days. The monsoons were nearing their peak, so the terraces were soaked and boggy, the mud grabbing at Kamala’s every step and leaving her limbs heavier than usual by the time nightfall came. Jeet may have been gone, but the burden of his work remained, along with Kamala’s own responsibilities—at home, in the fields, and in motherhood.

Word reached the village that her husband Jeet had flown to Jordan on July 3, but no one heard anything else, as the family had expected. Forty-eight days had passed since he landed in Amman to work at the five-star hotel, and months more might pass before a letter made its way from overseas to the village on the ledge, if one came at all. Phone calls were no easier. Just reach- ing a telephone required a two-hour walk out of the horseshoe and over the near hills to the edge of the village Taksar. There the Kunwar family ran a sort of one-room convenience store on the ground floor of their home by the side of a narrow road choked with buses spinning up dust en route to Kathmandu. The phone sat atop a waist-high display case stocked with Chinese flip-flops and Indian sweets. The Kunwars charged a few rupees per minute to make or receive a call. Phone messages could find their way to the horseshoe if and when someone stopped by the shop on their way to the ridge.

In the two and a half years since her marriage to Jeet, Kamala had come to work seamlessly with her mother-in-law in the daily running of the farmhouse. Kamala rose at about five thirty to light and stoke the kitchen fire. She fetched water from the large community well at the bottom of the hill, and then swept and, by hand, sponged every floor in the house before doing the same on the porch. She worked at her mother- in-law’s side to prepare meals and clean up when they were done. The two women grew closer as they split responsibility for managing crops and lives in Jeet’s absence.

Warm and affectionate with Kritika, the old woman also gave both her granddaughter and her daughter-in-law things Kamala had never had: a pair of slippers, children’s clothes, a sari, and even red bangles for Kamala’s wrists, which only Nepalese wives were supposed to wear. The level of security Kamala felt in the farmhouse exceeded anything she had conjured when Sati pitched Jeet’s family’s virtues under the cover of grazing cattle.

On the morning of August 21, 2004, nearly ten weeks after Jeet had left home, Kamala finished her chores and went down to the large terrace just below the farmhouse, where the red earth stood wet and empty. The time had almost passed to plot the family’s last vegetable garden of the year, where spinach, pumpkins, and tomatoes would take root and rise before the mists of winter climbed up around the ledge. Kamala brought the Chinese-made radio with her and set it on the garden’s edge. Jeet’s songs had long ago replaced those of Kamala’s sisters in the fields, but now Radio Nepal offered a comforting surrogate voice in his absence.

A bulletin cut into the afternoon music: a terrorist group in Iraq had claimed credit for kidnapping twelve Nepalese men, the announcer said, before reading the full name of each victim and listing his home village. The third name was “Jeet Bahadur Thapa Magar,” from “Bakrang Number Five, Gorkha.”

Kamala stood silent—not shocked, not panicked, but curious, questioning her ears and disbelieving. Names in Nepal include each person’s ethnic group, so virtually no one’s name can be considered unique, especially in an ethnic group as big as theirs. It would be a bit like all Americans having names such as “Peter Joseph Catholic Irish.” The name read over the radio could have belonged to anyone.*

“Kidnapped … Jeet … Magar … Bakrang Number Five …

Gorkha …”

Was that his name?

That sounded like my Jeet’s name.

That’s our village. It can’t be. Is it a mistake?

It must be another man with the same name. Is there another man with the same name in the village?

They must be wrong about the village. Did someone steal Jeet’s passport?

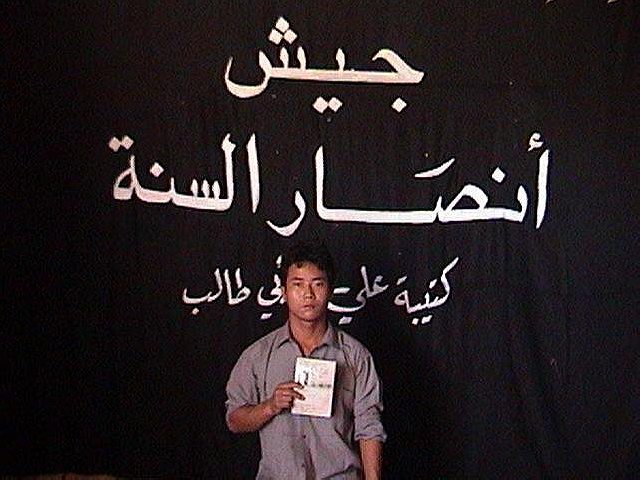

The terrorists, who called themselves the Army of Ansar al- Sunna, had first posted a statement on an extremist website the day before, saying that their “heroic fighters” had seized a dozen young Nepali men—the statement called them “infidels”— because they had come to Iraq to help “U.S. Crusader forces” who were “fighting Islam.” The twelve Nepalis were on their way to the American-occupied Al Asad Air Base in the restive Anbar Province about one hundred miles west of Baghdad. The posting included the name and village of each man, taken from his passport as a sort of proof of life. It promised to deliver pictures soon, “so that they will serve as a lesson to others.” The statement also included the name of a Jordanian company for which the men worked, something called “Bisharat.”

As Kamala stood on the barren terrace, music again poured from the radio, but she didn’t hear it. After some time, she gathered herself, picked up the radio, and hastened up the slope toward the farmhouse. Others heard the same news, which spread quickly across the village, albeit in confused and panicked fragments. Neighbors and family converged on the porch of Kamala’s home and inside the main room, just beyond the farmhouse’s threshold, and as more arrived, the rising sound of worried voices spilled out into the three valleys. Someone made a fire in the kitchen. No one knew anything, but everyone was afraid.

After a while, Radio Nepal news broke in with another bulletin that silenced the room. “Jeet Bahadur Thapa Magar,” the announcer said, followed by the government’s formal name for the horseshoe ridge that was his home. Someone screamed, and Jeet’s mother threw herself onto the hardened earth floor. Kamala froze in place. The assemblage of neighbors and family members melted into panic and grief.

Before the United States launched the Iraq War in 2003, Nepal’s government had declined an invitation to join what the administration of President George W. Bush had dubbed the “Coalition of the Willing.” Some British Gurkhas were posted in Iraq through their service in the United Kingdom’s armed forces, but even in the Nepalese capital, where electricity and television and printing presses had at least some presence among the elite, news of the American war did not play a significant role in daily life. Less than one-half of 1 percent of all Nepalis even used the Internet in 2004. For eighteen-year-old farm wives on the horseshoe ridge, the war was almost completely unknown if not unknowable, but Kamala did understand that Jordan and Iraq were two different countries.

Jeet’s eldest brother, Ganga, could not comprehend how Jeet had ended up in an American war zone, let alone in the hands of a terrorist group blaming him for serving the American occupation. Nor could he conceive what benefit anyone might obtain by kidnapping Jeet and eleven others hailing from one of the poorest and most powerless nations on earth. Surely, Jeet and the others would be freed, everyone told Kamala as they tried to comfort her. Kamala herself clung to the hope it was all a case of mistaken identity.

Within a day, a newspaper made its way from the city by bus, then after hours by foot across the hills to the village. The cover displayed a photograph the kidnappers had posted on the internet of the twelve Nepali men, aged eighteen to twenty-seven, assembled before a large black banner emblazoned with white Arabic characters as if gathered for some kind of macabre class photo. One hostage sat on the floor at the center of the picture, an American flag draped under his chin like a bib. He did not look into the camera, but instead stared down into the field of red-and-white stripes, the others assembled around him. Jeet stood on the far right, wearing the charcoal-gray shirt Kamala had helped him pack, his sleeves rolled up above the elbow, the darkness of the shirt accentuating his wan face and the weight of worry and sleep deprivation in his eyes. Inside their farmhouse, Kamala saw him in the photo and sank into despair.

The day after the radio bulletin, Jeet’s brother Ganga trekked down from the ridge before sunrise and caught a microbus for the city of Gorkha, the district’s administrative capital, desperate to find someone who could tell him something, anything. Along the way, he entertained fevered fantasies of borrowing money and bribing a Nepalese government official to send a message to the kidnappers on the family’s behalf. Many Nepalis understood they could get something done in their country only through the grease of a bribe. Ganga planned to speak with everyone he could find, even local journalists, hoping to discover that plans were afoot to negotiate for the men’s release, or that he could rouse someone to action.

Jeet’s family had no way of knowing it, but negotiating wasn’t a far-fetched idea. Hostage taking in Iraq was much more about capitalism than terrorism, at least in the summer of 2004, when there had been roughly sixty reported kidnappings of internationals in the seventeen months since the start of the war. The vast majority of victims were released, often in exchange for ransom. Americans by and large were the exception. This hit home in startling fashion when, a few months before the Nepalis were seized, a terrorist group kidnapped and beheaded a cell phone tower repairman from Pennsylvania named Nicholas Berg and dumped his corpse on the side of a road regularly patrolled by U.S. forces. The group made a snuff film of Berg’s execution—rough, shaky, out of focus, and gruesome—and then uploaded it to the Internet. It was among the first in a shocking new genre of global terror productions that would soon become all too common. It ensured that Berg’s murder captured headlines across America, on television and in print, for days. The video’s director and executive producer, and the reported executioner, was a man named Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, founder of the terrorist group that would eventually become ISIS.

Most had little idea there was even a war anywhere outside Nepal, then consumed by its own escalating civil conflict.

People in the horseshoe didn’t know a thing about Nick Berg. Most had little idea there was even a war anywhere outside Nepal, then consumed by its own escalating civil conflict. Maoist insurgents from rural areas of Nepal, including Gorkha, had launched the fighting in 1996. Inspired by the Shining Path guerrillas in Peru, who wanted to destroy all vestiges of the government and replace it with a peasant-led revolutionary regime, Nepal’s insurgents had similar goals in their own mountainous country and saw struggling farmers in the poorest regions as ripe targets for recruitment or intimidation. On October 1, 1999, the war even came to the village on the ledge. Scores of residents had gathered from across the horseshoe for a meeting organized by the Red Cross. Four Maoist fighters pulled from the crowd a man whom they suspected of informing. They confirmed his identity, bound his hands, and then cut his throat before the villagers. They left him to bleed out on the open terrace just above Jeet’s farmhouse, the spot that served as a wedding ground and public space.

Maoists also kidnapped hundreds of noncombatants across the country. The vast majority of victims were released following negotiations. In this way, the idea of insurgent kidnappings in the midst of a war seemed oddly familiar in Nepal. Because they often ended in freedom and tearful reunions, those kidnappings formed an almost reassuring backdrop as Jeet’s brother Ganga scurried from office to office in Gorkha city. He believed that with the right plan, his brother could come home. Yet, although each official and politician Ganga met that day personally guaranteed that the family’s concerns would be elevated to superiors all the way up to Kathmandu, these were the kind of bureaucratic platitudes that made clear the futility of the mission. There wasn’t even anyone to bribe, assuming such a fantasy ever had a chance of being initiated. “I felt so helpless,” Ganga would recall. “Nothing made sense to me, and yet I tried to do what I could.”

Despite the family’s inability to get answers or basic information, hope remained. Government-run Radio Nepal filled the air with encouraging news about efforts to free the twelve. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs had mobilized its missions across the Middle East. The Nepalese embassy in Saudi Arabia held unspecified discussions with unidentified “diplomatic personalities of different countries.” Messages went out from the Nepalese embassy in Abu Dhabi to the Iraqi embassy there, and also to the U.S. embassy. The Nepalese ambassador in Doha made a personal visit to the offices of Al Jazeera, the Arabic- language satellite news network bankrolled by the Qatari government, after the broadcaster received communications from the terrorists. That last meeting, at least, appeared to generate something tangible: on August 27, a prominent Iraqi cleric used his Friday sermon, issued beneath the blue dome of the largest Sunni mosque in Baghdad, to call for the release of the twelve Nepalis on the grounds that they were innocents. The plea from Sheik Ahmed Abdul Gafur al-Samarraie went out over Arabic-language radio and television.

Before long, the terrorists released a video, initially broadcast on Al Jazeera, showing the captive who had been draped in the American flag seated in front of a camera. His name was Mangal Limbu, and he was a twenty-two-year-old farmer from a district ravaged by the Maoist war. He held in both hands and in front of his face a statement written out in English by his captors. Desperately, he tried to read it aloud, but beyond an obvious condemnation of the United States, the young man’s words were almost completely incomprehensible, as would be the case for anyone barely literate in a foreign alphabet trying to read and speak words he simply could not understand, let alone form with his mouth.

Footage of ten out of the twelve men placed individually before the black banner came next. One at a time, each spoke into the camera, without notes and in his only tongue, Nepali. Several broke down after uttering only a handful of words. Jeet’s family didn’t see the video, and none of the men’s statements was publicly translated, broadcast, or published in the West at the time. Eventually, though, their words would come to haunt two nations, help drive a decade of investigations, and reveal clues that would threaten one of America’s most powerful corporations.

On August 31, ten days after news of the kidnapping, Kamala finished the brunt of the day’s work by midafternoon, climbed up to the bedroom she shared with Jeet, and stripped off her field clothes. She stepped into the sky-blue petticoat she used for bathing, pulling it up over her chest and cinching it tight, and then backed down the red wooden ladder off the balcony. She walked across the front of the farmhouse, past the wedding terrace above their home, and then down the steep trail leading to the community well.

The well is the biggest on the horseshoe ridge, carved into the green hillside below a thick canopy of ancient shade trees that keep the water cool. Two taps send continuous streams jutting out from a twelve-foot-long stone wall set against the hill. Splotches of emerald moss and black mold creep up and cling to the wall’s gray face, giving it the look of an abstract mural, and the waterfalls and slaps against stone slabs laid in the basin. Kamala leaned forward and dipped her arms into the stream running from the tap, then moved in, drenching herself. Clear mountain water, which runs strongest in the monsoon season, darkened her petticoat as she lingered, trying to wash away her anxiety. Eventually, she stepped out of the stream, bowed her head, and twisted and wrung her long dark hair, piling it into a bun on top of her head before heading back up the steep footpath toward the farmhouse, her petticoat and hair dripping. A drizzle had started falling from the sky and onto the mountain.

She kicked her feet out of her flip-flops, stepped up onto the porch, and crossed the threshold and went into the main room of the ground floor. She heard a whimper, turned, and, once her eyes had adjusted to the darkness, saw one of Jeet’s nieces sitting on the floor in the corner, crying. Her two sisters-in-law then entered, filling the house with wails. They told Kamala that people had been hearing on the radio that the terrorists had murdered Jeet and the other men. Their executions were on a video like the one of Nick Berg. Kamala began hyperventilating.

Jeet’s mother had already left. She’d gotten the news earlier, from the same woman weeping in the corner, and had asked her grandson, who was also in the house, if it was true. He said it was. For a moment, Jeet’s mother stood still, and then, not knowing what to say or do, and noticing the drizzle outside, she asked her grandson to bring in the clothes that were hanging on the balcony. Her grandson refused. “What’s the point of anything now?” he said. With her grandson’s refusal, the truth washed over the old woman, and she felt numb. She shuffled out of the farmhouse, off the porch, down the footpath, and toward the gloomy shade cast by thick jungle that had never been carved away, wanting only to wander until she was lost and starving—perhaps the cleanest and oldest way in the hills to end one’s own life.

After a time, the old woman reached a cluster of homes along the path. A distant nephew saw her there. He had heard the news. Everyone had. “Auntie, where are you going?” he called out. She did not answer, and kept walking. The young man then drew even with her, took her hand into his own, and led her to his house. He kept her there for a time while he finished some chore. “You should go back home,” he told her. When she refused, he kept her longer. “Do you think you can hold me here like this forever? I’ll go wherever I want,” she said. Again, he took her by the hand, leading her all the way back to the village on the ledge, where her family and the other villagers placed the old woman on a makeshift suicide watch, making sure no one left her alone or able to wander free.

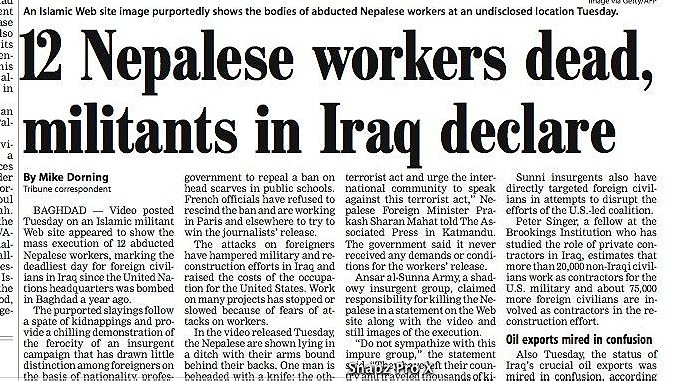

The killings made news internationally, albeit briefly, that same night. “The twelve Nepali men were kidnapped ten days ago by an extremist Islamist group, Ansar al-Sunna,” a BBC News anchor said. “And today, all twelve were brutally murdered, shot in the back of the head, or beheaded.” ABC World News Tonight used still frames taken from the execution video, as anchor Peter Jennings introduced a correspondent in Baghdad. “The video showing the slaughter of twelve Nepalese construction workers was posted on an Islamist website this morning. Most of the four-minute tape is too gruesome to broadcast. These are edited stills. One of the hostages is beheaded; the others are lined up, facedown, and shot at point-blank range,” said ABC’s Mike von Fremd. The piece lasted a little more than a minute.

By then, attacks on foreign contractors in Iraq were old hat, and had dominated headlines for months. They were the softest targets, the outer ring of the American occupation, and they were deliberately targeted in an effort to cripple it. The violence had started in full force fie months earlier on March 31, 2004, a year after the U.S. invasion, when Iraqi insurgents ambushed a convoy of security contractors near the center of Fallujah, hitting their SUVs with a fusillade from automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. The four American men killed that day worked for a company called Blackwater USA, and were guarding a delivery for a catering firm. Insurgents dragged the four from their smoldering vehicles and paraded their charred corpses through streets filled with cheering mobs, before hanging them from a bridge spanning the Euphrates River. Video of their deaths aired worldwide. It was a signal moment in the war, when the rage against the U.S. occupation, at least from within Iraq’s once-dominant Sunni population, stood naked for the world to see and made undeniable the reality, size, and force of the insurgency.

In the days, weeks, and months that followed Fallujah, a wave of attacks crashed down on truck drivers, interpreters, engineers, oil workers, and more security contractors. There were roadside bombs, ambushes, and kidnappings. There was Nick Berg. By the end of the summer of 2004, these murders no longer shocked. Nearly one hundred contractors were killed in the months following Fallujah. News outlets ran the story of the Nepalis’ murders as a contractor death story like any other—but it was not.

For starters, this was far and away the deadliest such massacre to date, although this fact generally did not make the news. Comment from coalition authorities in Iraq also seemed strangely absent, unlike in the aftermath of other such killings. And while death in Iraq was routine, everything else von Fremd said to Peter Jennings made little sense. Nepali men? Nepal was one of the remotest lands in the world, and it wasn’t a member of the Coalition of the Willing. Yet these men—these “construction workers,” who had probably barely ever seen a paved road let alone ridden in a car before they left Nepal for the Middle East, men who quite likely had never plugged anything into a wall socket or pulled open a refrigerator door or turned the handles on a faucet—were the victims of the deadliest such massacre in Iraq? How on earth had they gotten there, from mud-floored homes and villages without roads—and then four thousand miles away, across heavily guarded borders, and into a fortified American war zone? Who had brought them? What were they doing there? What possible vital skill set could a dozen farm boys from the foothills of the Himalayas have held for the American government? And for whom were they working?

In addition to raising more questions than they answered, the news reports that followed understated the horror of what had happened to the men.

In 2004, there were no online social networks in Nepal, or smartphones to carry them, and there was virtually no internet penetration, yet the video spread rapidly across the country.

The film opens at eye level of the man behind the handheld camera, looking down on the ground at Mangal Limbu, the farmer who had been draped in the American flag. His torso cuts horizontally into the center of the frame from the left side. He is lying on his back in the desert dirt beneath the open sky. His hands are bound behind him, and the knot they create beneath his back causes him to twist slightly onto his side. A bright chartreuse shirt is in tatters beside his head. The shirt has been sliced away from his body, exposing his bare chest, his shoulders, and his arms. His head and eyes are wrapped with a wide white blindfold, which looks like a strip torn from a bedsheet. The same white cloth is wrapped around his bare abdomen and is apparently what’s binding his hands.

A man in a desert camouflage uniform moves into the picture from the top of the frame, wearing a matching baseball cap with the bill pulled low to hide his face. He crouches above his captive and, with his left hand, cups the young man’s chin to steady the head. Roughly, quickly, the camera zooms in, filling the frame with the farmer’s head and the white blindfold. With his free hand, the killer draws a large hunting knife across the farmer’s throat and begins to saw, slicing through the cartilage of the windpipe and into the carotid artery running up beside it, but stopping short of severing the spine. Bright red blood spills into the dirt and begins rapidly spreading across the absorbent white blindfold.

The man with the knife quickly backs out of the frame. The camera lens widens, pulling back with him. The farmer writhes. Another man stands above the farmer, stepping down on the young man’s right hip to force him flat onto his back before the world. His vocal cords are severed, making it impossible for him to speak, but ghastly squeals of air, almost porcine, scream up from his lungs and through the gash in his windpipe, each squeal lasting the length of his breath, each growing longer and higher-pitched the more desperate his body becomes for air.

Finally, he falls silent. Thirty-five seconds have elapsed. His corpse is decapitated. In the remaining three and a half minutes, the eleven other men, lying prone in a ditch, are shot in the back and the back of the head, one by one. They are not bound. They submit to their deaths, and to their last moments beneath the sky becoming political theater, although it is difficult to imagine how they could have done otherwise.

In 2004, there were no online social networks in Nepal, or smartphones to carry them, and there was virtually no internet penetration, yet the video spread rapidly across the country’s cities through makeshift public screenings, the media, and then word of mouth. Within just one day, tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of angry rioters choked the streets of Kathmandu and other cities.

They spontaneously and simultaneously attacked scores of manpower agencies throughout the Kathmandu Valley and across the nation, beginning with Moon Light Consultant, the broker in Kathmandu that had sent Jeet and the others to Jordan. They ransacked offices and burned the passports of would-be workers, shattered windows, burned signboards, and smashed or burned virtually every piece of office equipment they could find inside agencies around the nation. Often, they later returned to the same brokerages to make sure they had damaged everything possible. They attacked virtually every business affiliated with the manpower agencies in the entire foreign employment network, from clinics providing pre-employment health checks to photo studios where workers were sent for passport pictures. They went after the offices of travel agencies and the airlines. They attacked the biggest national newspaper that made money publishing the public notices for foreign jobs. Almost no one in the system, or even on its fringes, went unharmed. In response, the government instituted a nationwide curfew that lasted four days.

The sprinkling of stories on the riots that appeared in the international media highlighted attacks on Muslim institutions. The mob’s real target, the system sending Nepalese farm boys off to foreign employment, had been overlooked in the coverage. The true meaning of the nation’s rage would become clear outside Nepal only once the footage of each man speaking in Nepali, as he stood before the black banner, had been translated and disseminated beyond the Himalayan kingdom.

Calm returned after a few days, and a sort of national mourning settled over Nepal.

Mourners filled the farmhouse. Everyone tried to comfort Kamala, but it sounded as if they were all speaking from a distant room. She heard words but could not discern meaning in them. Only Kritika seemed clear, fixed in her sight. The child was not yet two years old, the same age Jeet had been when his father died and Kamala had been when she lost her mother.

Jeet’s eldest brother, Ganga, initiated the rituals of death. After the murders were announced, people across the country prayed for the return of the men’s bodies. Hindus and Buddhists believe the soul cannot be free until the body of the dead person is cremated. “We said, ‘Give us his breath, bring him home alive,’ but now we asked for his body—give us his breath or his body,” Ganga said. Soon they knew neither would be theirs.

Ganga met with elders on the horseshoe ridge to discuss something he had heard of but never seen, something that he believed could free Jeet’s soul: an ancient ritual for creating and burning an effigy of a dead man whose body has been lost, perhaps at sea or in a faraway battle. Priests crafted such an effigy from dried holy grass, called khus. The grass is rare in the foothills of the Himalayas, but it does grow in monsoon season. Ganga began scouring the jungles each day.

The meaning of loss, not just the loss of life but also the loss of a loved one’s remains, is acknowledged through the reconstruction of his body from the stalks of the sacred grass. Three hundred sixty stalks are to be used, a figure believed by the ancients to be the number of bones in the human body as well as the number of days in one of their calendar years. Specific prayers are recited at each stage, beginning with the same prayer that is uttered when a child is born. There is even a mantra for placing the heart of the man who is lost into the effigy. There were no priests on the horseshoe ridge, so Ganga did his best to adhere to the rituals as he had learned them from the old men. He prayed aloud and spoke to the effigy as he crafted it, as if speaking to his brother. The effigy was about the size of a newborn. As a child, Ganga had held his baby brother the same way after his birth. “Even though you suffered a terrible death, I hope you will find a place in heaven, and that the afterlife is more beautiful,” he said as he bound the head and arms to the body with twine.

About two hours before sunset on the ninth day after Jeet’s death, Ganga and almost every man in the village gathered at the farmhouse. Kamala, bearing a set of Jeet’s clothes and a pair of his shoes, backed down the ladder from the room she had shared with her husband. She handed the clothes to the men and then hid herself away, unable to bear the thought of what was to come. The men placed the effigy on a small bier fashioned from bamboo poles. Ganga held the bier from the front, like a pallbearer, and a cousin took up the rear. They led the other men in a procession over the footpath and down the western side of the ledge behind the horseshoe, trekking for about an hour, until they reached the Sauney River in the valley below. There they gathered wood and made a pyre on the river’s edge. Dousing the wood with kerosene, Ganga placed Jeet’s clothes and effigy on top.

Stalks of dried khus blacken and bend above a fire, but they do not wisp up into the wind as embers or ashes, especially when densely twisted together. Some varieties of the grass are even made into perfume, and the sweetness of the white smoke’s smell is soft but discernible in the air. The men watched the fire. As the flames twisted in his eyes, Ganga prayed again for his lost brother, wondering if there could be freedom or justice for Jeet’s soul. The fire dimmed as darkness settled into the valley.

Ganga removed his shirt and sat on the riverbank. Hindus believe hair is an adornment and a symbol of vanity and that one must be free of vanity to grieve for a departed soul, so one of the men took a razor and shaved Ganga’s head clean by the water’s edge. Ganga rose and wrapped a white cloth around his waist, like a pauper Hindu priest. He left his chest bare and placed a white scarf on his head in the style of a bandanna. Such are the Nepalese symbols of mourning. The men began their trek back up the mountain and into the jungle darkness. In the bed she had shared with Jeet, Kamala tried not to think of the fire, but she couldn’t keep the image of its hungry flames out of her mind. She felt her love burning on the mountain river.

[Header image: from the cover of The Girl from Kathmandu, courtesy of the author]