The Place to Go if You’re Hungry for Knowledge and Couscous

The Place to Go if You’re Hungry for Knowledge and Couscous

Couscous in Tunis

Finding the door to Mohamed Bennani’s library is not straightforward. But if you can navigate through Tunis’ labyrinthine medina, through the market stalls and palaces embedded into walls, and if it’s lunchtime on a Wednesday, then that door will always be open.

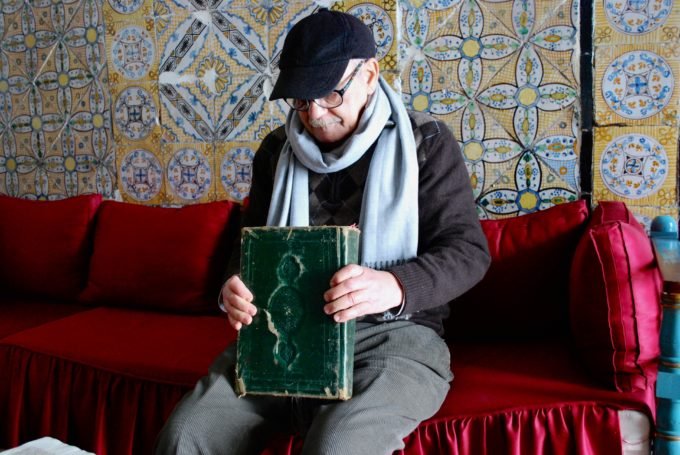

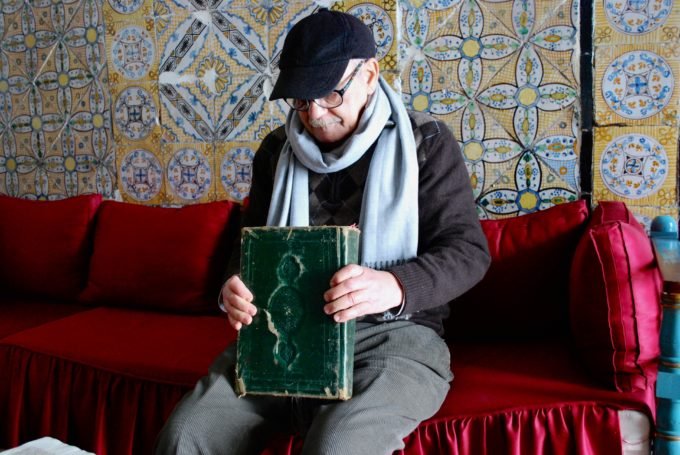

Bennani has an open-door policy. For 23 years, the Tunisois book-preserver and collector has been welcoming guests into his home on Wednesdays for a meal of couscous.

His family library, Beit Al-Bennani, which dates back five generations, has become an important collection of Tunisian literature and heritage. I was lucky enough to have a friend, an archeologist who uses the library for his research, guide me through the maze to Bennani’s place.

Bennani meets us and leads us through a tiled door-frame into a book-filled room, where a sociologist of religion, a cultural guide, an art collector, a documentary filmmaker, and an exchange student chat and dip bread into oil. Bennani makes introductions, inquires about people’s lives, and tries to direct them to something in his library. For me, he had an old photo album of Iranian dancers and a few dusty books about Tunisia written by British historians.

Then we move across the white, tiled courtyard to the dining room for the main event: a huge bowl of couscous topped with butternut squash, courgettes, okra, carrots, spinach, all soaked in harissa with a side of spiced pulses. I ask for the recipe, and Bennani feigns horror: “It is a family secret!” But the menu is not important. People come for le partage—the sharing.

Bennani’s Wednesday couscous gatherings continue his mother’s tradition of offering food to the less fortunate after Friday prayers. Their guests stopped coming after a while, he says, so they started giving money to charity instead. But Bennani wanted to continue his mother’s tradition. He welcomes anyone who is hungry for knowledge or, of course, couscous. He moved the meal to a Wednesday to “secularize” the occasion.

Unlike in his mother’s day, Bennani’s lunch guests—artists, cultural figures, and scholars—are not in material need, but during Tunisian dictator Ben Ali’s rule, the couscous sessions provided another kind of service.

“In Ben Ali’s time, we spoke freely in the house and people came here exactly for that. It was a little patch, a little space of freedom. We forgot the outside, and so we could speak more freely,” Bennani says. This, in spite of the policemen who would stand outside his door, and who sometimes came in for lunch in disguise. “We began to recognize them,” Bennani says.

Bennani says he stays out of politics, but during the Tunisian revolution in 2011, his house was a base for protesters to come and charge their phones, get a glass of water, or to rest and get medical attention if they were injured. “When we found out that Ben Ali had resigned, everyone cheered and hugged and kissed each other.”

Bennani still serves couscous every Wednesday.