The real estate listing for my summer vacation home would make most realtors drool. Our house sits on two lush acres, fronts a pristine lake, sleeps six comfortably, and exudes a cozy, rustic charm. There is a sauna, a secure driveway, and a flourishing vegetable garden.

When we bought it in 2002, we paid $2800 for it. A remarkably low price, to be sure, but a reflection of the house’s one significant drawback: it is located in eastern Belarus, Europe’s last Stalinist state. It is what the Russians call a dacha (pronounced with a hard ch as in “cha-cha.”)

Without a doubt, that’s a very long way to travel from Brooklyn, a journey which, door-to-door, requires about 24 hours in each direction, but my family and I do it with pleasure each year. For my wife, whom I met while working in Moscow in the 1990s, it is a homecoming. She grew up in a mining town not far from where the house stands, and her brother and many of her high school friends still live there.

I share a little of that spirit, as I have vacationed here every summer for the last 15 years, but I am, and will always remain, an outsider. For many of my neighbors, I am the only American they have ever met. To them, I am an exotic, treated like a rare hothouse flower. It’s ok, for example, that I do not throw down a double-shot of vodka in one gulp, like the men there do. It is understood that Americans are pansies in this regard.

Regardless, it is where I happily spend every summer, where my children are learning to speak Russian like natives, and where, as any homeowner knows, I have completed countless—and far from painless—dacha renovations.

Home improvements are often nightmarish under the best circumstances; now, imagine yourself in a small authoritarian nation steeped in Soviet economic policy. There are, of course, the usual hassles that one would encounter in modifying an American home, but in Belarus, things are made far more complicated.

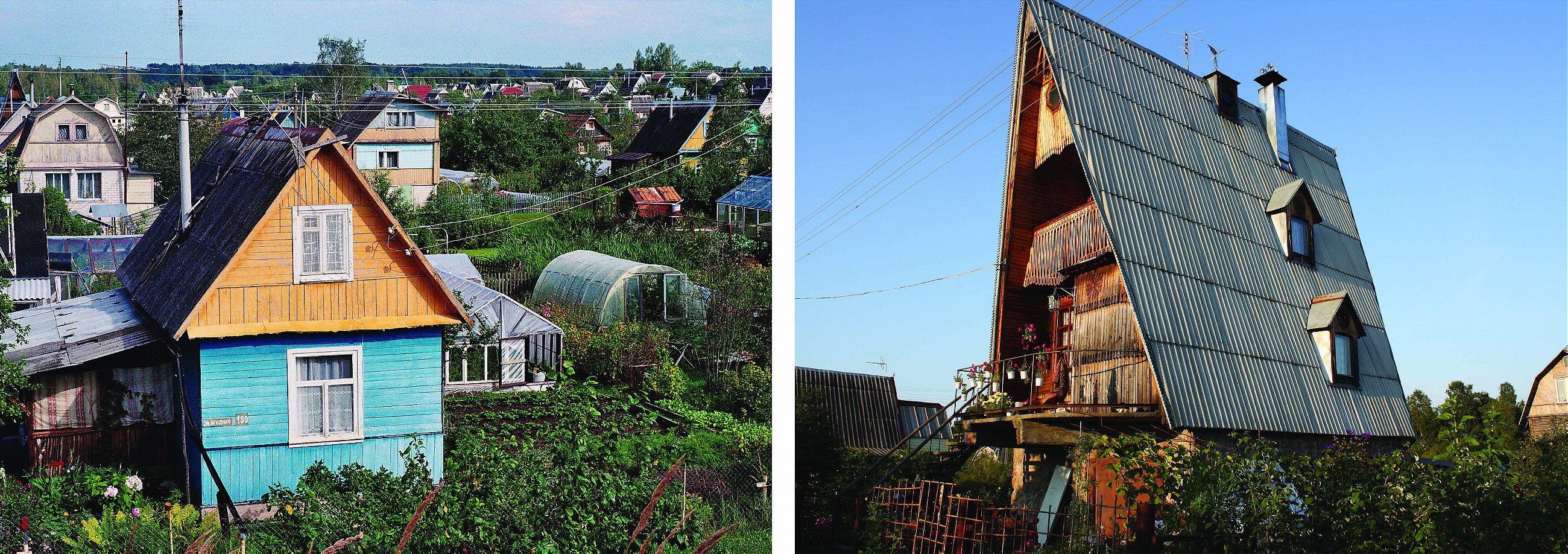

Unlike many American country homes, we are not exactly nestled deep in the countryside. The house is part of a dacha community consisting of about 500 homes, set on a tract of land which was, during Soviet times, set aside by the government to give comrades who could afford it a way to escape the cramped conditions of the urban housing blocs.

Some of the landowners use their parcels to grow food, but most have erected dachas. In part because there was no such thing as a “contractor” in Soviet times, almost every house was built by its owner, from the foundation up. There are no architectural plans, no zoning laws, no committees, and no safety standards. Every year or so, there is a woeful tale about a home that burned to the ground because of an electric fire or a faulty propane connection.

This DIY approach to things leads to some rather quirky results. The very first house one encounters upon entering the community is shaped like the head of an Egyptian pharaoh, while another looks like it was drawn from a Grimm fairy tale. With no rules on the size of the house footprint, many of the homes are packed cheek to jowl with their neighbors, not exactly what one would hope for in a country home.

On the top of most owners’ to-do list is plumbing. A water main runs through the community, but it is designed more for growing gardens than house-holding. Water is turned on three times a week for a few hours each time. The idea is that you would water your garden during these periods, but if you are not home, or the community chairman (whose job it is to open the valve) is busy or unavailable, it simply doesn’t happen.

As I said, there are no contractors. Even if you can find someone who is willing to help, you have to make sure that he (and it is always a man) doesn’t show up drunk or take off during the middle of the day to spend his earnings on booze. This has not stopped us, however inadvisably, from tackling some ambitious projects.

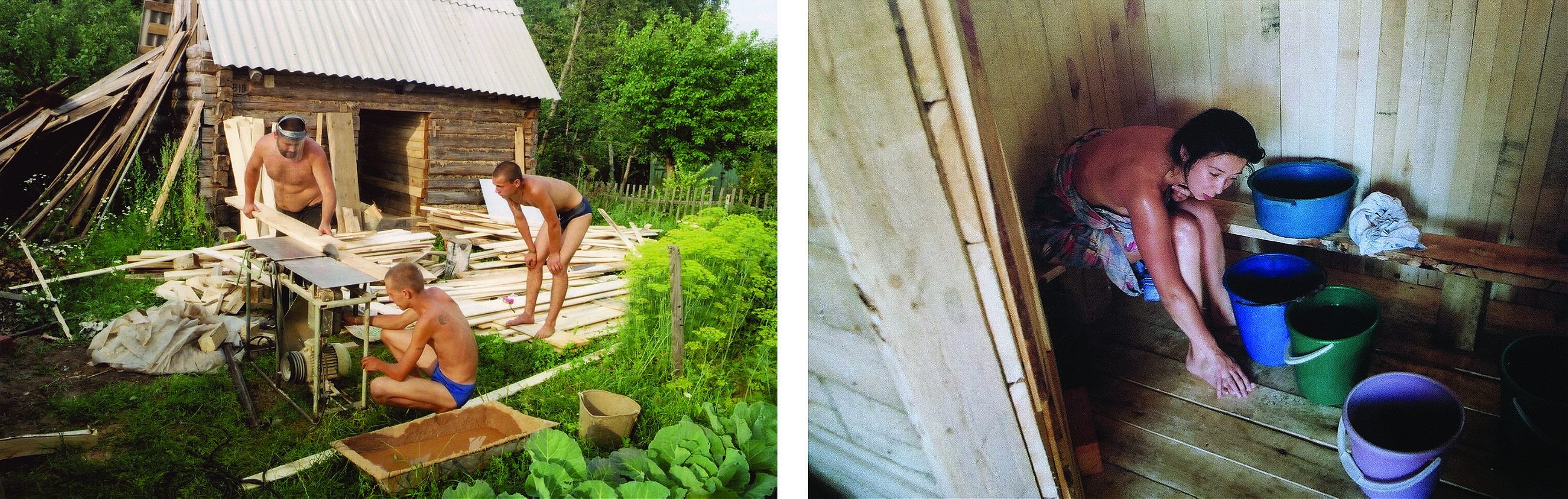

For bathing, we added a sauna, known in Russian as a “banya.” The banya is an essential part of the dacha experience; a “good steam” is a deeply embedded part of Russian culture. Our bathhouse is constructed from timbers that we found for sale in “From Hand to Hand,” the Russian version of Craig’s List (though it is still published on actual paper). The pieces were hauled to our house by truck and assembled, Lincoln-log style, at the back of our garden.

Before disassembling the structure, the previous owner numbered the beams so that they could be re-assembled on a new foundation, but it’s not as though they came with an IKEA-style instruction manual. They were incredibly heavy and bulky, requiring at least two people to move and stack, work that was heroically carried out by my brother-in-law and two local teens whom he enlisted to help him. This being their summer vacation, the two boys showed up for work each morning dressed in bathing suits and nothing else. Miraculously, no one was hurt.

Another major project was the construction of a bridge that could link the front half of the property with the back half. Though the parcel is two acres in size, a huge portion of it was unused and overgrown, because it was cut off from the front by the water main and a deep, muddy drainage ditch. It took us two summers to clear the brush and roots from that back acre, and another summer to construct a bridge, which we devised by looking at photos online.

The design we chose relied on using cinder blocks as piers. After a few phone calls, we were able to locate a supply depot that sold them, but we quickly discovered that they did not have the same material integrity as their American cousins. As we loaded and unloaded them from the car, the corners crumbled off like blue cheese. When we got them onto the work site, our neighbor laughed heartily. But we were able to manage it by slathering the blocks in cement. That was several years ago, and I am pleased to report that they are still holding strong.

Even finding the simplest supplies is challenging due to the shape of the marketplace. Forget the web and big box stores. Instead, Belarusian consumers rely on the hundreds of individual stalls lining the so-called “trading centers” in the nearby town, a small city of about 340,000 people called Vitebsk.

These giant emporia, some indoors, some outdoors, are the lifeblood of the local economy, delivering the many goods that the state-managed system is unable to provide. Most of the businesses re-sell inventories that they have hauled in the trunks of their cars from nearby nations such as Russia and Poland.

It is to these utilitarian aisles that ladies come to find fashion, men go to check out power tools, and kids go to ogle the latest toys. This is Main Street, Belarus. But among the cramped shops, figuring out who has what, or doing a little comparison shopping, even when you want something as simple as an L-bracket, involves traipsing up and down the crowded market for hours at a time.

The vast corps of small-scale entrepreneurs who run the stalls at the market are trying to carve out a living in a system that frustrates at every turn. With all the taxes, arcane laws, paperwork, and bribes needed to open a business, it is a miracle that these people get out of the starting gate in the first place, let alone earn a profit.

But to be sure, someone is getting rich somewhere. The town is dotted with construction projects, and someone controls the numerous gleaming supermarkets and gas stations that line the main roads.

Rising to this level of mega-business is unimaginable to the ordinary Belarusian. If you don’t have the right connections, it is impossible to even get in the door, let alone take a seat at the table. And amassing capital on your own is unheard of, as everyone around you will take a piece of the action. This is perhaps the most infuriating aspect of life in this part of the world: the culture of bribery that permeates everything. For every rule, there is a counter-rule, giving the cops and bureaucrats who control the flow of paperwork a license to make things up as they go along. Lawyers, courts and “laws” are merely window dressing. Anything can be had for the right price, or the right connections. I am, strangely enough, especially vulnerable in this realm, as my accented Russian lets bureaucrats and cops know that I am a foreigner and they imagine that my pockets are bulging with cash. Anytime we are stopped by the police— and it happens remarkably often, whether or not we have committed an infraction— I am under strict orders to keep my mouth shut.

And change will not come easily to this part of the world. The head of state, Alexander Lukashenko, is your basic president for life, a post he has held since 1994 and to which he was elected for a fifth term in October 2015. Opposition voices are routinely stifled and a free press is entirely absent. Furthermore, the political will that might give rise to dissent (as it has in some eastern European states) is very rare. Most of the people in Belarus grew up under the Soviet system, where citizens’ participation in government was a cruel joke at best, a cause of imprisonment at worst. For several generations, politics for most people took a backseat to getting food on the table and a bottle of vodka in the freezer. Now, even though food and booze are now plentiful, the culture of apathy remains strong.

This filters down to the very lowest levels of life. For example, the neighbors of our dacha community, would, in theory, share many interests in common, but nothing ever happens to benefit the group. We pay tax on the property, but none of that money gets spent locally; it all goes to the regional center or the capital, where I imagine it ends up in some bureaucrat’s bank account. There is no town council and meetings to discuss community affairs never happen. Once, a few residents tried to raise money to pave the rutted dirt road that runs through the community. They raised enough money to put down about 500 yards of blacktop, then ran out of funds. That was a few years ago; the road is still rutted, largely impassable during the rainy season.

In this manner, life at the dacha remains largely unchanged from summer to summer. There is always a moment each year when I grow frustrated with the place. As an American, I am particularly vexed by the way our Belarusian friends and neighbors—all of them honest, hard-working people—are forced to slog daily through so many indignities. But they don’t see it that way. This is the life they have always known, and the last thing they want is my pity. Like them, I resign myself to making it work as best as possible. They are adept at focusing on the delights of what sits immediately in front of them: the beauty of the birch tree, the mystery of the forest, the majesty of the clear, blue sky.