At the Madrid Ritz, the lead concierge is in the business of yes.

Through the cavernous lounge, where ladies with taut faces and tight Chanel jackets gossip over dainty sandwiches; past stiff-backed waiters, skirting around sherry-stupefied old men; and beyond the purplish Doric columns that flank the baroque lobby, Borja Martin Guridi stands behind an ornate hardwood desk. He is the head concierge at the Hotel Ritz in Madrid: the man charged with helping guests satisfy any (legal) desire.

Dressed in a gray suit with his hair combed back in a sweep of brown, Martin is clean shaven and fresh-faced, almost boyish in spite of his 42 years. But his youthfulness and energy belie his experience. Through his job, Martin has met more film stars and shaken the hands of more heads of state than almost anyone in Spain.

Martin must be a person of absolute discretion, a man for whom gaining access to luxury is quotidian. He is the caller behind the impossible restaurant reservation, the furrowed brow behind the last-minute private jet charter, an inconspicuous provider of conspicuous consumption. He is the concierge who, in his words, “achieves the impossible immediately, but takes a little longer with miracles.”

Martin grew up in Madrid, and as a boy wanted to travel the world. But he was a pragmatic dreamer, and believed that his best chance of achieving this goal was to work in the restaurant and hotel industry. He studied hotel management and, as part of his degree, worked in hotels and restaurants in countries such as England, Germany, and Italy. It was on these trips that he perfected his five languages and his manner with customers.

In 1999, soon after graduating, Martin was offered an apprenticeship at the Ritz in Madrid, working at the reception desk. He was fascinated by the hotel. “I would imagine all the things that had happened here behind closed doors: the big business deals, the diplomatic accords, the scandals, the famous people that had passed through.” For him, the Ritz was more than just a hotel; it was a museum.

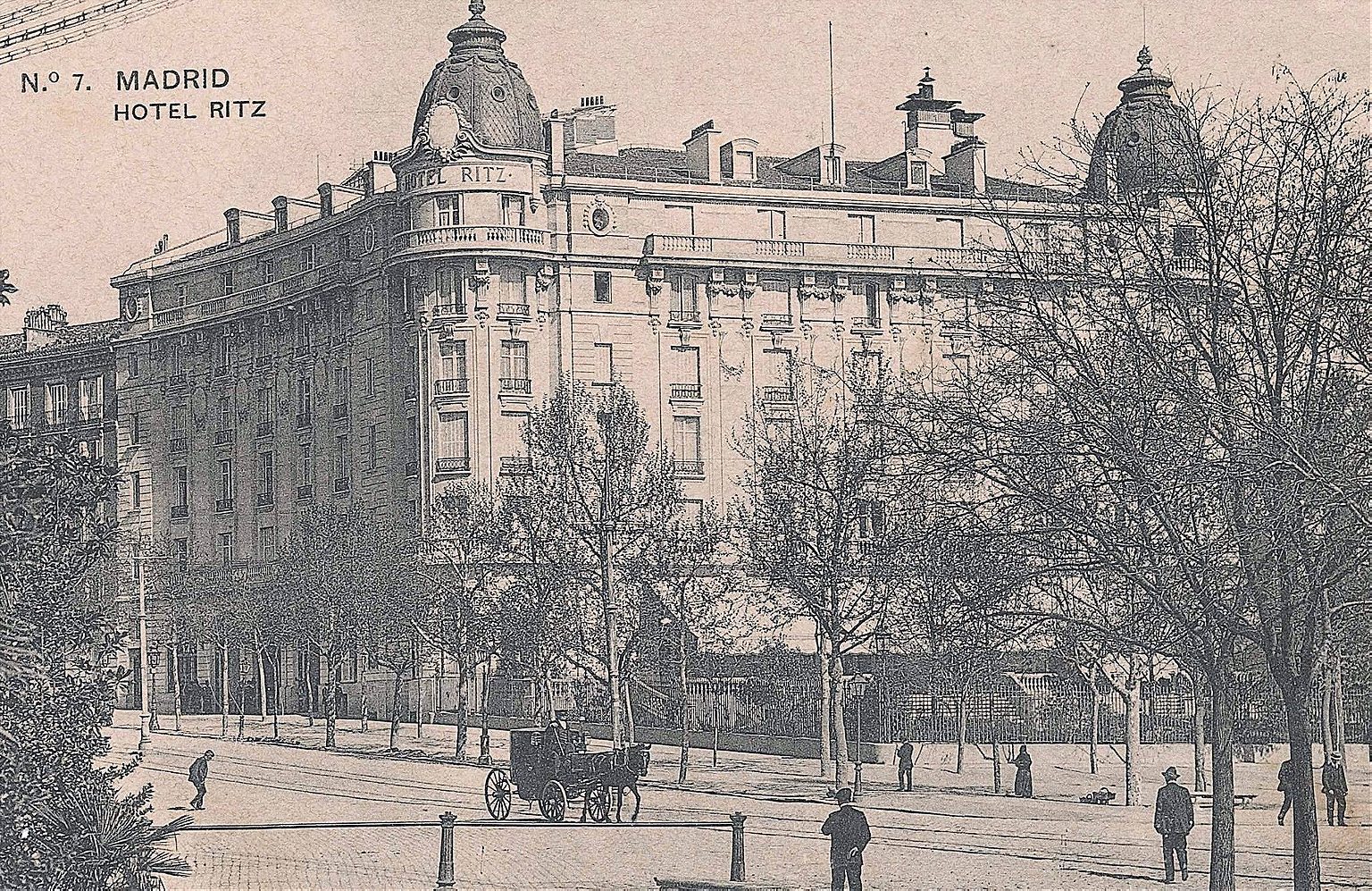

The Madrid Ritz was the initiative of King Alfonso XIII of Spain who, at the turn of the 20th century, requested the services of César Ritz—the “king of hoteliers, and hotelier to kings”—to help him build Europe’s most luxurious hotel. Alfonso, who spent a great deal of his time travelling the continent, wanted his city to have a hotel equal to those in other major capitals. He knew the world was changing; the railway had shortened once time consuming trips and made travel cheaper. The industrial revolution had seen the rise of a new and wealthy mercantile class. It wasn’t just the aristocracy that was travelling: people from different backgrounds were also visiting Madrid, and the King wanted a suitable place for them to stay. Charles Mewes, the same architect who designed the Ritz in Paris, lead the project, and the hotel opened on Oct. 2, 1910.

Since then, it has served as a refuge for the world’s elite; a temporary home for autocrats, Hollywood actors, and fastidious British prime ministers. When Frank Sinatra visited, he asked for a white piano in his room. When Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu stayed, he sent his guards down to the kitchen to make sure the chefs didn’t poison his food. And when Margaret Thatcher stopped over, she asked that the concierge install a desk of specific dimensions in her room, because, as she said at the time, she “couldn’t work on any other.”

Far from the political district of Moncloa or the Royal Palace in the center of Madrid, the hotel has been the private retreat from which the country has been unofficially run. As Fernando Serrano, the ex-Ritz waiter-cum-renowned Spanish journalist wrote in his memoirs, the “hotel was a diplomatic palace.”

In that first year, Martin learned what was behind this glamour, how luxury and tranquility were maintained by regimented discipline, and that, while indolence pervaded the lounge, underground, in a warren of hidden offices, the hotel’s staff worked ceaselessly.

In daily morning meetings, the staff discussed the coming and going of guests: which ones were new, which ones were returning, and, if the latter, their likes and dislikes. Maids ensured that every cushion was symmetrical, every table and chair aligned, and that the curtains in each of the 162 rooms were a third drawn, never more. On top of this, there were night porters, day porters, chauffeurs, bellboys, waiters, laundry workers, and a kitchen filled with 40 chefs, cooking meals on demand, day and night. There was even a person whose sole job it was to maintain the hotel’s 10,000 square meters of carpet.

Martin was intrigued by one figure above all others: the concierge. Before arriving at the hotel, he had had little idea of the concierge’s function. Like many people, he had imagined a bellboy in a nicer suit. But the role’s history was much richer than that.

Michael Romei, head concierge at the Waldorf Towers, writes that what we now know as the modern concierge came into being centuries later, after the fall of Napoleon in 1815. In a Europe liberated of war and conquest, travel was less dangerous, and transport, due to technological advancements, more sophisticated. Romei explains that as the number of travelers increased, so did the new hotels built to cater for them.

These luxury hotels brought with them a new type of tailored service. One such role was the porter, who, charged with taking care of luggage, organizing carriages, and guarding the room keys, was “omnipresent during the guests’ stay.”

This omnipresence, combined with the rising number of international visitors, necessitated the ability to speak many languages. Often one of the few employees who was multilingual, the porter, like the modern concierge, became indispensable to the guests.

Romei also posits that it wasn’t until the founding of Les Clefs d’Or (the Golden Keys) that the porter-cum-concierge became commonplace in high-end hotels. The group, founded in Paris on Oct. 26, 1929 by Pierre Quentin, was created so that Paris’s concierges could trade ideas and contacts to improve the level of service in their own hotels. Starting out with only ten members, hand-picked by Quentin, the group gradually grew, standardizing the role of the concierge and spreading it to other hotels in major European cities.

In 1952, the Les Clefs d’Or held its first international summit. There, members coined the motto “in service through friendship” and ordained that the group would henceforth become an international brotherhood, allowing a concierge from a hotel in London to contact a member in Paris for advice. Prospective members would enter the organization through the recommendation of current associates, and once in, would be officially presented with the golden keys, a small badge to be worn on the lapel. Today, the Clefs d’Or spans some 60 countries and boasts some 4,000 members, of which Martin is one.

In those years, he watched his boss get a Mexican passport for a donkey that had been won in a bet. He sent a parrot bought on a whim via courier to Brazil, lifted weights in the hotel gym with John Travolta, and had tea with Harvey Keitel. He learned how the Ritz name could open almost any door. How, although there may not be a table available for an ordinary customer, there was always one available for a guest of the hotel. But more important than any of this, he learned that nothing should be deemed impossible until it had been proven to be so. As Walter Ferrari, former head concierge at the Excelsior in Rome, says, “If a concierge says yes, he means maybe, when he says maybe, it is a no, but if he says no, he is no concierge.”

Martin also performed less glamorous tasks. He organized hundreds of airport transfers, made thousands of restaurant reservations, and showed visitors the main tourist attractions in Madrid many times a day. Martin says that even in those everyday encounters there was always some subtle problem that he had to solve. “Often guests would come looking for approval of a decision that they had already made,” he tells me. “Even more frequently, a guest would come to me with no idea what he or she wanted.”

In each of these situations, he slowly teased out the relevant information. “It’s like that game ‘Guess Who?’” Martin says. “You have a list of questions in your head and, according to the guest’s answers; you begin to eliminate the type of person he or she might be until you reach the point where you are confident your recommendation is right for that person.”

Discretion is part of being an excellent concierge

Now, as head of the concierge desk, a position he assumed in 2015, Martin is a wily character. He guards his workplace secrets and his opinions closely. When he speaks, he is sincere but careful never to offer strong opinions. He discusses the requests of his clients without ever seeming to ridicule them. He never judges, only listens. “Discretion is part of being an excellent concierge,” says Martin. “I always have to respect the privacy of the guests and the choices that they might make.”

There is an anthropological aspect as well. Martin’s team often attends courses about what to expect from particular cultures. They learn about customs and manners, so as not to offend a guest on his or her arrival. One story is often repeated to illustrate this element: before Martin’s tenure, when Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia visited the hotel, the staff had to walk backwards whenever Selassie—who for the Rastafarians is God incarnate—would wander the communal areas. Turning your back on the Messiah was considered of great offense.

In a world of instant gratification, where apps such as Uber and Lyft are taking over car-transfers, and online food guides are reducing the need for concierges to recommend restaurants, Martin’s expertise and professionalism must be more noticeable than ever.

“Whereas before, perhaps 50 years ago, the concierge would have been a person who had made their way up the ranks of the hotel, now, it requires serious qualifications,” he says. When Martin interviews for a position, he expects prospective candidates to have a relevant university degree, excellent administrative skills, and to speak at least three languages.

“Borja spends a great deal of his time preparing and training his teams,” says Inma Casado, a spokeswoman for the hotel. The team goes on fact-finding tours around the city, ploughs through stacks of lifestyle magazines, employs memory experts who help them remember the names and backgrounds of clients, and regularly attends seminars on guest relations.

The concierge desk has even engaged with the technology that threatens its existence. The team uses Twitter to keep regular customers abreast of the changes occurring in Madrid and Spain. Martin knows that although he cannot go head-to-head with technological advancements, he can embrace them, and use the extra time they permit him and his team to specialize in other areas. Martin himself is always plugged in. He wears an earpiece like that of a Secret Service agent and is always talking to his team: giving feedback, relaying customer requests, and checking in for updates. Even when he is not working, at home with his wife and two children, he is always connected to WhatsApp, available should a regular guest ask for him specifically.

The job may be unremitting, but Martin matches his clients’ demands with an indefatigable stoicism, which hides any sense of exasperation that might result from his daily routine. He manages this, he says, because he enjoys the job.

He admits that the position has changed his ideas about wealth. “Money isn’t everything, but whether we like it or not, it does open many doors.” But he will confess little else. He insists that he is not jaded by the insatiability of his guests or cynical in the face of what, to some, could be considered self-indulgent and extravagant requests. “Most of the requests—getting opera tickets, reserving restaurants or closing down boutiques for private shopping—aren’t extravagant,” Martin says.

Martin is bound to diplomacy by the rigors of his job, and will not be tempted into criticizing his customers. What’s clear is that he is a man focused on results, a man focused on delivering the seemingly impossible in ever more nuanced ways, and a man uninterested in the word no.