The world saw the Gambia’s Yahya Jammeh as a brutal, eccentric dictator. But his hometown still loves him.

Kanilai, THE GAMBIA—

The billboards appear almost immediately after we exit the highway: First, the dictator gazes off in contemplation, then he smiles on a canvas that commemorates his 50th birthday, then assures us we are entering a “baby-friendly community.” So far, everywhere else I’ve been inside the Gambia, a tadpole-shaped West African country that clings to the banks of the river that gave it its name, I’ve struggled to find any public images of Yahya Jammeh, the army lieutenant turned autocrat who ruled the country for 22 years, building one of the world’s most extreme personality cults.

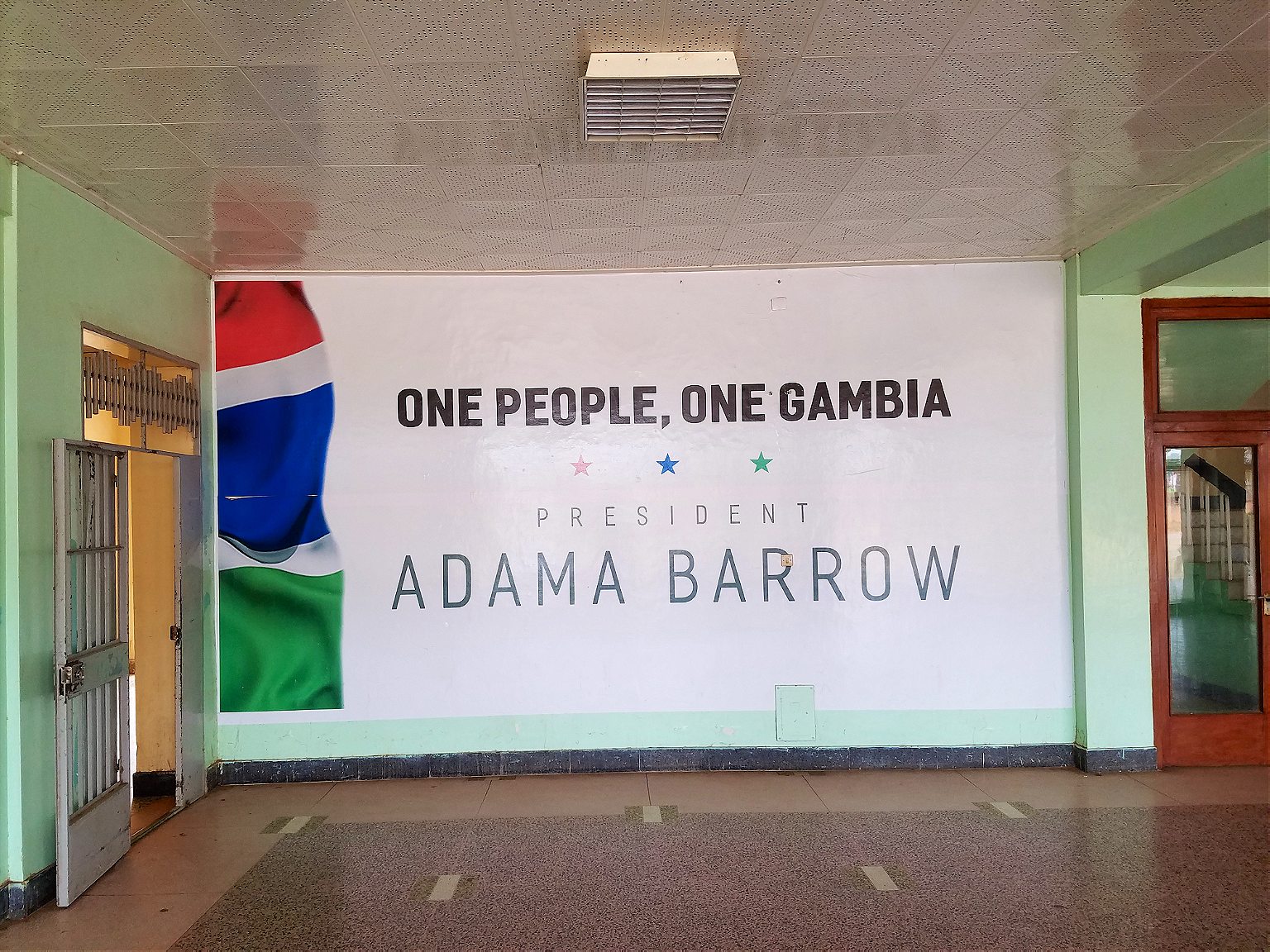

Jammeh, whose exploits as president included threatening to slit the throats of gay people, personally administering a dubious herbal remedy for HIV/AIDS, and claiming he’d rule for “a billion years,” fled the Gambia in January under the threat of regional military intervention after refusing to accept a surprise defeat by the property developer Adama Barrow in elections last December. In most of the country, once ubiquitous banners depicting the president in his trademark robe and cap had been taken down in favor of less Orwellian signage. The most popular refrain, on official billboards and graffiti scrawled across concrete walls, celebrated the country’s nascent democracy with the hashtag #GambiaHasDecided.

In Kanilai, though, I knew things would be different. Here, in the former president’s hometown, a village of a few thousand people set under the canopy of towering silk cotton trees, I’d been told to expect an acute sense of nostalgia for the departed son—and for good reason. Prior to 1994, when a 29-year-old Jammeh seized power in a bloodless coup, the town had been a quiet backwater, home to small-scale maize and groundnut farmers and little else. Under Jammeh, it boomed with the fruits of political patronage: an elaborate presidential palace, complete with a resort hotel, zoo, and sports stadium; free electricity and water for all villagers; and giant vats of stewed meat served up daily for anyone caring to feast.

As president, Jammeh spent much of his time in Kanilai, making the 80-mile trip from the capital, Banjul, several times a week and using the town to host many of the country’s most important functions. Samba Jawo, a reporter for Gambia’s leading newspaper, the Daily Observer, who’d agreed to tag along on my trip, had visited the town more than a dozen times to cover conferences, wrestling tournaments, cultural events showcasing the traditions of Jammeh’s minority tribe, the Jola—even special days of service where individuals from across the country would volunteer their labor on the former president’s sprawling farm. Samba’s editors, tasked with feeding the dictator’s ego, would invariably put these articles on the newspaper’s front page.

“Any story from Kanilai had to be a lead story,” Samba tells me as we approach our first military checkpoint. “And you had to write good things. Even if you went to the farm and you saw only three people weeding, you had to say it was a ‘massive turnout.’ ”

I’d come to Kanilai as part of an attempt to get a fuller picture of the “new Gambia”—a country that had caught my attention following Barrow’s election victory because it struck me as a glaring exception to the retrenchment of liberal democracy occurring elsewhere across the globe. After a 2016 that had elicited the systemic shocks of Trump and Brexit, and the bend toward autocracy in once relatively liberal emerging market countries like the Philippines, South Africa, and Zambia, the Gambia’s trajectory seemed just the opposite. It is a place that, against all odds, has escaped from the grasp of a man who wielded absolute power and by the time I visited in May, was in the throes of a new, albeit messy, democratic order. In order to understand the Gambia taking shape in Jammeh’s wake, though, I wanted to see where he had come from, how “his” people had lived, and get a sense of where they saw their place in the new Gambia after the fall of their patron.

While nearly all modern African states are the creations of colonial powers, the Gambia is a particularly egregious example of European borders drawn with little concern for local inhabitants. Its thin, elongated geography, the result of an historical British presence on the river in a region otherwise dominated by the French, effectively divides neighboring Senegal in two. The partition also divided native communities: Jammeh’s Jola people, for example, constitute a small minority in the Gambia, but the bulk of the population resides in the southern Senegalese region of Cassamance, whose borders extend to the edge of his property in Kanilai.

Like any capable autocrat, Jammeh exploited this to his advantage. While in office, he exacerbated tensions between Cassamance and more-developed northern Senegal by supporting the Movement for Democratic Forces in Cassamance (MDFC), a low-grade Jola-led rebellion which began as a fight for independence but increasingly evolved into a racket smuggling timber, drugs, and weapons from which Jammeh is believed to have personally benefited.

It’s no surprise, then, that Senegal would jump at the chance to force Jammeh out of power—an opportunity that came following December’s electoral shock. Before the poll, few in the country believed that Jammeh, who’d won past elections handily, could ever lose a presidential ballot. Yet the opposition in 2016 was more united and better organized, and the incumbent was overconfident. Jammeh was so sure of his popularity, several Gambians tell me, that he did not even bother to tamper with the vote as he had in the past. Although Jammeh initially accepted Barrow’s victory, he later reneged on his promise to step down, sparking a six-week political impasse that continued as Barrow was sworn in as president at the Gambian embassy in the Senegalese capital, Dakar. The same day, Senegalese troops entered the Gambia as part of a military intervention coordinated by the Economic Community of West African States, backed by ground forces from Ghana and air and naval power from Nigeria. The Gambian army offered no resistance. Two days later, Jammeh and his wife boarded a private jet to Guinea, and later Equatorial Guinea, where they remain in exile. A cargo jet allegedly followed carrying bundles of cash and Jammeh’s fleet of exotic cars.

It’s been four months since these events when our beat-up Mercedes taxi rolls into the center of Kanilai, and the atmosphere has changed dramatically. Aside from a pair of roadblocks leading into town, the security presence is minimal compared to Jammeh’s days in power, and Kanilai itself is eerily quiet. Driving slowly to the end of the road, past baobab trees and a rows of dilapidated shops, we arrive at the palace entrance: a black-and-white iron gate, which sits slightly ajar, next to a wall adorned with another Jammeh billboard: this one commemorating the 22nd anniversary of the “revolution” that brought him to power. Just inside the wall, a group of Gambian soldiers occupy a shaded watchtower with a mounted machine gun pointing toward us.

Beyond the gate I see a concrete archway rising into the treetops. Beyond that lies the palace itself, the zoo, and the thousands of acres of irrigated land where the president, relying mainly on volunteer labor, farmed groundnuts, cashews, rice, maize, millet, and even fish. We attempt to enter but are rebuffed by the man in charge, a twenty-something civilian wearing a Chelsea jersey and flip-flops, who sits on a wooden bench brewing tea atop a small charcoal stove. His boss isn’t around, he says, so we’d better come back later.

As we wander off, I’m struck by how ordinary everything looks, at least on our side of the gates. The houses, made of mud or brick and iron sheets, are no more elegant than those I’d seen elsewhere in the country. At the midday call to prayer, men crowd inside a mosque that resembles a storage shed. (A more permanent mosque stands half-built with wooden scaffolding behind it—its Lebanese financiers, we would learn, had pulled out when Jammeh fled.) Even the village chief, an elderly man who tells us he’s Jammeh’s cousin, hardly resembles the beneficiary of a president who grew rich from pilfering the nation’s coffers: The week after my visit to Kanilai, Gambia’s minister of justice froze Jammeh’s domestic assets and announced he had stolen at least $50 million from the state over the previous decade. Yet when we arrive at the chief’s home, a mud brick dwelling no different from the others, he greets us with bare feet and a tank top. He only speaks the local language, Jola, which Samba does not, so he calls over another cousin, David Kujabi, to talk to us.

Kujabi, a slight man in his 40s who wears a green cap bearing the image of the former president, is willing to talk and quickly becomes our de-facto Kanilai tour guide. As the local head of Jammeh’s Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC) party, he’s spent much of his adult life spinning Jammeh’s record in power and is still adept at it. In an impassioned discussion that lasts over an hour, he does his best to counter the dominant narrative of Jammeh—that of a megalomaniac human-rights abuser who looted his country while its population suffered—that’s taken root in the wake of his downfall.

“No matter what bad you do, there must be something good you do,” Kujabi tells me, before describing Jammeh’s building of roads and hospitals, his bringing of electricity to rural communities. Above all else, he says, Jammeh kept crime to a minimum, enabling Gambians to move freely at all hours, tourists to flock to its Atlantic coast, and businesses to flourish. “He doesn’t joke with security at all,” Kujabi says, speaking in the present tense as if Jammeh were still president. “For the past 22 years, we have never gone to bed without peace of mind.”

Many of Kujabi’s arguments do match up with what others tell me about the Jammeh era. Despite Jammeh’s theft of public funds, several businessmen I speak with say the fear he inspired helped keep more systemic corruption in check, which is now beginning to resurface. Gambia’s security, made possible by the police state he commanded, had indeed attracted foreign investors and boosted the Gambia’s emergence as a tourism hotspot: one particularly popular with gray-haired men and women from the U.K., Netherlands, and Germany, who arrive in winter months for cheap sun or sex or both.

Although the atmosphere along the country’s main beachfront “strip” is as seedy as I’ve seen, tourism does bring critical jobs and foreign exchange to a country where formal economic opportunities remain limited. While Jammeh did built infrastructure, his country remains poor enough that thousands of young Gambians flee the country every year along the “backway:” a highly perilous journey that takes them across the Sahara, through a lawless Libya and, for the lucky ones, to an overcrowded boat across the Mediterranean into Europe.

The stability Jammeh fostered also came at a cost. During my two weeks in the country, Gambians from various walks of life describe the state of fear they lived in during Jammeh’s days in power: never sure whom they could and couldn’t trust; always careful to keep any thoughts of subversion hidden. Some of his moves came straight from a standard dictator’s playbook: carefully controlling the press; buying the loyalty of individuals in opposition strongholds and using them to infiltrate friends and neighbors; employing state security forces and a paramilitary group, the Jungulars, to stifle dissent and, if necessary, make the country’s undesirables “disappear.”

At times, though, his antics were just plain weird. In 2009, he believed his aunt’s death was caused by sorcerers. Jammeh’s security forces rounded up nearly 1,000 suspected witches from his home region and detained them in an abandoned building in Kanilai. According to a Human Rights Watch report based on interviews with men who took part in the operation, many of the suspects were beaten, tortured, raped, and forced to drink a hallucinogenic potion that caused six to die of kidney failure.

Kanilai, it turns out, was often a stage for the dictator’s dirty work. Foday Conta, Gambia’s police spokesman, later tells me that investigators have been scouring Jammeh’s farm for the bodies of two Gambian American businessmen who disappeared from a beachside resort in 2013 and are believed to be buried on his property. Authorities suspect the remains of other Jammeh victims, including a group of murdered Ghanaian migrants, were dumped inside a well adjacent to the ground of his palace, just over the border in Cassamance. Efforts to exhume them, however, have been compromised by landmines planted by rebels in the area. The previous month, Conta tells me, a father and two sons there were killed when their horse cart rolled over a mine as they searched for firewood.

“They were cut into pieces,” he says. “It was only the horse that survived. But the tail, everything else went off.”

Investigators have been scouring the grounds for bodily remains

Back in Kanilai, as Kujabi and I continue our discussion, he brings up the exhumations before I have a chance to ask, when I attempt to elicit his help getting access to the palace. Kujabi says he doesn’t have the authority to let us beyond the gates and tells me our prospects are doubtful, in part because investigators have been scouring the grounds for bodily remains—presumably those of the Gambian Americans. When I press him further, however, he insists he was never aware of any bodies being buried in Kanilai. He also does his best to dodge other questions about Jammeh’s human rights record, suggesting in a roundabout way that the president was simply doing what he had to do to maintain his grip on power. After all, as the survivor of at least four attempted coups—including, most recently, a failed 2014 attack on his other presidential palace in Banjul—Jammeh had good reason to be suspicious of possibly subversive elements in his midst.

Kujabi prefers to spend most of our conversation spelling out the difficulties that Kanilai’s residents are now facing. At the surface, there are the day-to-day hindrances: Water and electricity are no longer free; some households are claiming that their power has been cut off even though they’re making payments. Other residents tell me hunger has increased because locals are no longer receiving food handouts, which Jammeh often provided in exchange for labor on his farm. Suleiman Jarju, a tailor who runs a small shop a few miles up the road from Kanilai, says many locals were so reliant on Jammeh for sustenance that they neglected to keep up their own plots. A general lack of money all around, and the end to Kanilai’s former circuit of festivals and concerts, means business at his shop is almost nonexistent. A few of his neighbors have even abandoned their houses and fled the area.

For Kujabi, the most pressing concern is security: At President Barrow’s request, ECOWAS forces remain in the Gambia to help stabilize the country, including a unit of Senegalese troops stationed nearby, which Kujabi says feels like an occupying power. Like many other Gambians I’d speak with, he’s suspicious of Senegal’s motives and worries about Dakar’s leverage over Barrow—particularly given its role in Jammeh’s ouster.

A month before our visit, Senegalese forces had shot and wounded three Gambian soldiers in Kanilai as they attempted to gain access to the road leading to the palace. David tells me he worries the next confrontation could be a “bloodbath”—a statement that strikes me as hyperbole. However, two weeks later, during a protest against the ECOWAS mission in front of Jammeh’s palace, Senegalese troops shot and killed a 63-year-old Kanilai resident. Tensions in the town spiked again in July, when authorities began searching the palace for looted assets, which one local described to Reuters as “witch hunting.”

Elsewhere, other cracks had started to show though the veneer of the post-Jammeh euphoria. On my last day in the country, I attend a press conference in Banjul at the national police headquarters, arranged after residents of a coastal village attacked a group of officers who’d attempted to carry out court orders to demolish illegal dwellings—a turn of events that would have been unthinkable under Jammeh. In a speech to residents of the town who’d been summoned to the capital, the interior minister, Mai Fatty, delivers a plea to order that reminds me more of a high-school principal scolding misbehaving students than the words of a high-level national official.

“Yes, there is a new Gambia, and we want you to be free,” the minister, a slight bespectacled man, yells to the crowd as his voice begins cracking. “But anybody who feels that this is the new Gambia, and therefore you can go about flouting the law, you’d better think again.”

Sitting in the audience, I think back to the Jammeh billboards I saw upon our entrance to Kanilai: images that, in spite of his killings, abuses, and grand-scale theft, had still projected an image of strength—even respect—that the new democratic Gambia appeared to be lacking. Although Jammeh was unquestionably a tyrant, he had held things together—in that particular, unseemly way that dictators so often do. I wondered, moving forward, to what extent the glue would stick. Despite the arrest of nine Jammeh intelligence operatives, including his former spy chief, many loyalists suspected of crimes are still at large. Their presence, as well as that of rebels he once coddled just over the border in Cassamance, means the threat of unrest in the area remains.

But despite the tensions inspired by the Senegalese forces, the overarching impression of my visit is that Kanilai’s inhabitants have neither the resources, nor the appetite, to mobilize a true resistance. After finishing our chat on the chief’s doorstep, Kujabi leads Samba and me on a tour of the town that reveals its residents, for the most part, are settling into their new normal.

First, we stop at his extended family’s compound, where neighbors relax under the shade of a mango tree, teenage girls play a game of dice, and sheep meander past a circle of logs sticking out of the sandy ground, which Kujabi tells us is the grave of Jammeh’s grandfather. After that, we wander past the gates of the now-closed hotel, stop at Kanilai’s only restaurant for a lunch of lukewarm chicken yassa, and make one last effort to gain entry to the palace: This time, we’re turned down by a second gatekeeper, a middle-age man whose T-shirt is emblazoned with the slogan used by Jammeh to promote agrarian self-sufficiency: “Grow what you eat; eat what you grow.”

Anticipating we’d be unable to enter, Kujabi has brought us a memento from his house that strikes me as a sort of consolation prize: a campaign poster from last December’s election. Jammeh, in his robe and cap, poses proudly above an inscription of his official title: H.E. Sheikh Professor Alhagi Dr. Yahya A.J.J. Jammeh Babili Mansah. The last two words, which he adopted in 2015, loosely translate as “builder of bridges.”

At the bottom, in bigger font, the poster reads: “Gambia in Safe Hands. Vote for A.P.R.C. 2016.”

Maybe he’ll come back for the next election? I ask, unsure how to interpret the gift.

“You never know,” Kujabi says. “Anything is possible.”