The vicious Boko Haram movement in northeastern Nigeria targets children and schools.

Part I: “We Will Not Stop Coming”

Boko Haram has staged hundreds of shooting rampages and suicide bombings at schools across northeastern Nigeria. The stories in this three-part series are those of the survivors. Words, images, design, and video by Rahima Gambo.

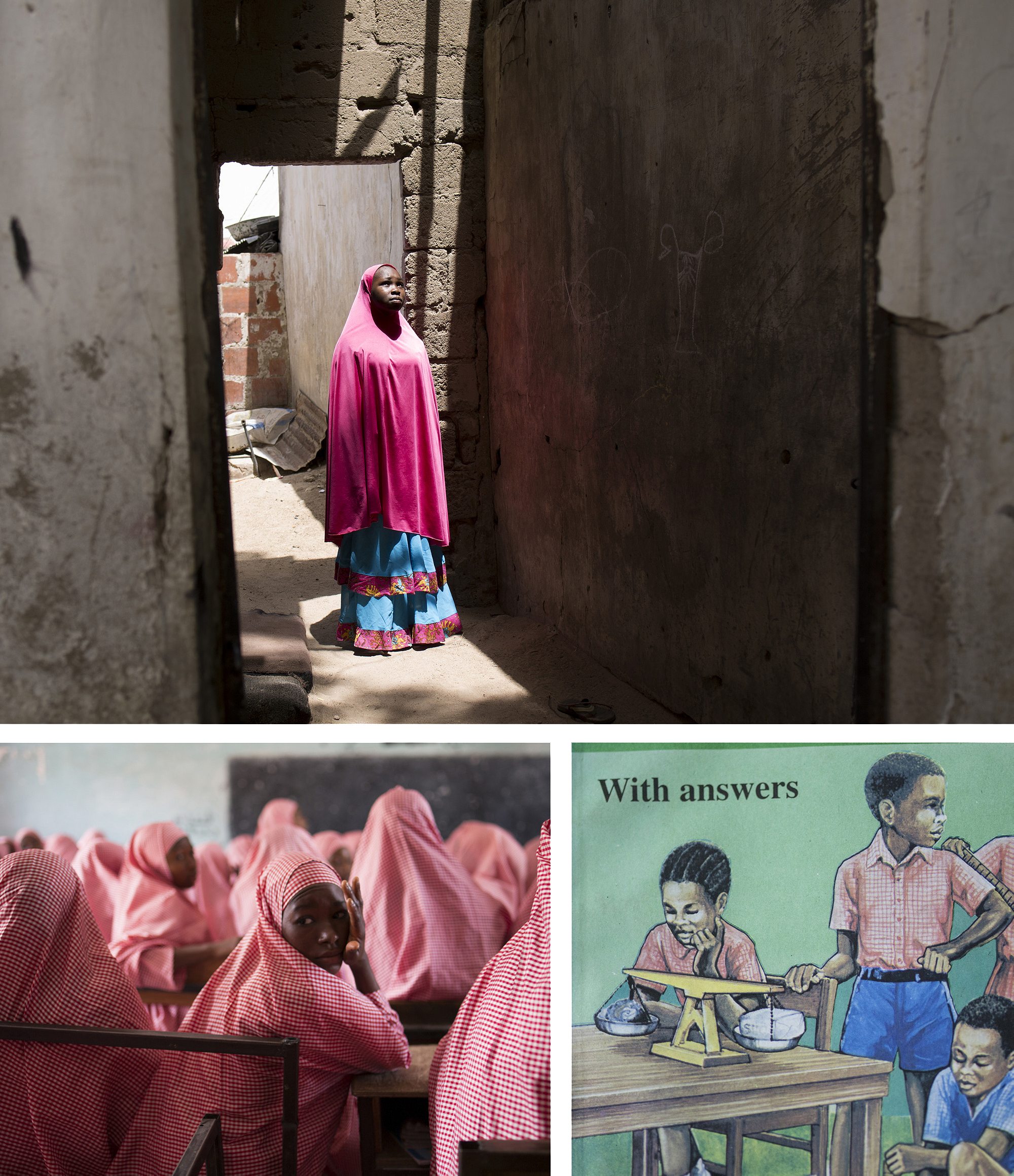

The school day in Maiduguri, Nigeria, begins at 7:30 a.m. At the entrance gate of Shehu Sanda Kyarimi Government School, a teenage boy stands with a metal detector in his hand, running it over fellow students’ bags and clothing to check for explosives. In their white-and-red uniforms, the students form two snaking lines, one for boys and the other for girls. With 2,800 pupils and a single gate, a bottleneck inevitably forms. Yet no skips or shortcuts are allowed.

According to UNICEF, one in five suicide bombers for Boko Haram, the notorious terrorist group ravaging northeastern Nigeria, is a child. Explosives are strapped to tender young flesh and sent to wreak fatal havoc in crowded places, including schools. In 2015, Boko Haram carried out more than 150 suicide attacks. Shehu Sanda Kyarimi is taking no risks.

As students trickle through the gate, a teacher shouts orders about morning duties in rapid Hausa, the local language. A few boys pick up stick brooms and start sweeping the school’s property in the lackadaisical way teenagers do when forced to perform a task they don’t like. The dust and heat of the morning form a yellow haze that blankets everything in sight: the U-shaped, single-story classroom blocks, the spacious courtyard that they hug, and the students loitering around the edges.

Four years ago, on an unassuming morning just like this one, disaster struck. On March 18, 2013, six Boko Haram gunmen stormed into the school’s courtyard firing bullets in every direction. A teacher and student were killed; three other pupils were injured. Shehu Sanda Kyarimi was one of three schools in Maiduguri attacked that day.

“We were running against the wall,” Zara Bashir, 18, says of being trapped in the courtyard with her terrified peers. She speaks quietly, her kohl-lined eyes looking downward and rarely meeting mine.

“After that,” she adds, “we stayed at home.”

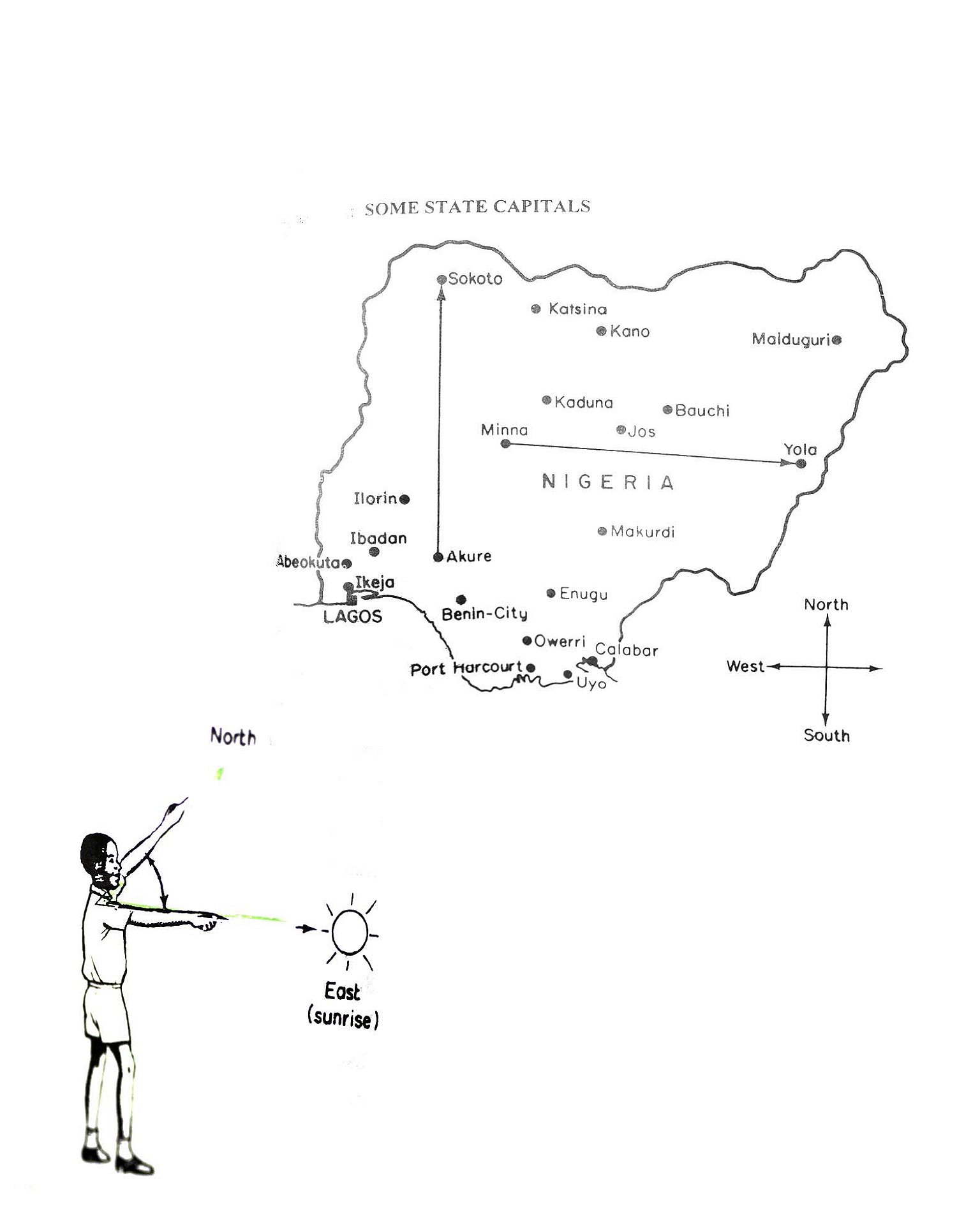

Boko Haram has targeted schools throughout its years-long rebellion against the Nigerian state. Traveling around the country’s northeast, the effects are plainly visible. Bombed and burned school veneers dot the landscape. Between 2009 and 2015, according to a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report, more than 900 schools were destroyed; another 1,500 were forced to close. Thousands of students were injured, abducted, or killed.

The attacks on schools are strategic, rooted in Boko Haram’s founding principles. It began in 2002 as a radical Islamic youth organization that denounced secular education. In Hausa, the group’s name means, “Western education is forbidden.” Fueling its anger was a series of half-baked development policies that left social inequality, mass unemployment, corruption, and poverty entrenched in Nigeria’s heavily Islamic north.

Mausi Segun, a researcher for HRW, says that in some cases Boko Haram has attacked schools to punish people for disobeying its religious philosophy. She also points out that the Nigerian military, which has been battling the group for several years, uses school buildings for military purposes—making them even more vulnerable to terror attacks.

Maiduguri, a major economic hub, sits in Borno State near Nigeria’s borders with Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. At the height of Boko Haram’s insurgency, from 2013 to 2015, bombs and gunfire were common in the city’s soundscape. Militants sometimes stopped students on their way to school. “They were telling students in uniform, ‘Do not go to school, [or] we will kill you,’” says Sadu Mala, principal of Shehu Garbai Secondary School. Some children would put their uniforms in plastic bags and change into them after they arrived at school to avoid being harassed. Others stopped coming entirely. Mala, his beard graying and his eyes tinted red with weariness, remembers a drop in enrollment.

After a particularly intense spate of attacks, Borno State took drastic measures, closing almost all public schools in the spring of 2014. The neighboring states of Yobe and Adamawa followed suit. “It really affected us seriously,” Musa Inuwa Kabo, the Borno State commissioner for education, tells me. “It halted the determination we had to catapult the education sector to a higher pedestal.”

The government relocated some students to public boarding schools in less troubled areas. Many, though, were left behind. Some private schools stayed open, but even the students whose parents were able to afford the necessary fees weren’t safe. Zara Bashir attended a private school for a while, and Boko Haram regularly terrorized it. “They used to beat our teachers, and make us lie on the ground,” she recalls. “They would storm into the school frequently until finally they burned it.”

In 2015, a few months after Boko Haram pledged its allegiance to the Islamic State, President Muhammadu Buhari assumed power promising a more aggressive approach to dealing with the group. The Nigerian army pushed terrorist cells from northeastern cities. Maiduguri reopened several schools, including Shehu Sanda Kyarimi and Shehu Garbai. When I visited, they’d been operating again for about seven months.

Students are picking up the pieces of an education interrupted. Yet they have changed irrevocably: They have become reservoirs for the fears and uncertainty of an entire nation.

During recess at Shehu Garbai on a hot spring day, students gather in the dappled shade of a mango grove. The smaller ones climb branches to pluck fruit that for many will serve as a meal. Shehu Garbai now accommodates local students as well as ones displaced from rural areas by Boko Haram’s violence. After missing a year or two of school, some students have been placed in classes with children younger than they are. Resources are strained. Classrooms intended for just 35 students hold more than 100.

Four female friends in their late teens talk under the trees. For several years, they’ve wondered when setting out for school each day, What if I never return? In April 2014, more than 200 young girls were abducted from the town of Chibok, about 80 miles to the south. They were young women who spoke the same language as these four, who probably listened to the same music, and who whispered similar secrets to their friends. “I was afraid to go to school because of unexpected attacks,” says Rashida Musibau, 18. “In my neighborhood, Boko Haram killed a lot of people and burned a lot of houses.”

The Chibok incident, which sparked the international Bring Back Our Girls campaign, is the most famous crime that Boko Haram has committed against students. The specter of the abductions—most of the girls have never been found—is everywhere. Young people who are alive and back in school carry it, along with their own horrific experiences. Like hairline fractures, the impacts are invisible to the naked eye but painful deep within.

Ahmed Murfa, 18, survived a February 2014 massacre at the Federal Government College (FGC), a public boarding school, in the town of Buni Yadi. Boko Haram besieged the campus, killing 59 young boys. Murfa escaped and eventually made his way to another school in Damaturu, the capital of Yobe State. Once passionate about science, he now focuses on the arts because he doesn’t have a choice: His new school lacks properly maintained labs.

Abdulmumini Abba is a lanky teenager with a wide smile and dark shadows underneath his eyes. He was displaced from the town of Dikwa, near the Chadian border, in 2011. “I will never go back,” he tells me bluntly, remembering how the militants killed people indiscriminately in his poor agricultural community. Today, Abba lives with about 100 other boys in a Maiduguri tsangaya, a religious school where students learn to read the Quran. Many of his classmates are orphans, but Abba’s mother and siblings live nearby. He also attends classes as Shehu Sanda Kyarimi. Abba wants to be a doctor.

At 21, Babakura Shuwami is one of the oldest students in Shehu Sanda Kyarimi. He is originally from the town of Bama, where in 2014 Boko Haram gathered hundreds of local residents into a dormitory and executed them. Shuwami left after a different massacre, in which several of the teachers at his school were assassinated. His family moved to Maiduguri, and he turned to petty trading, pushing wheelbarrows at a local market for about 10 cents per customer. Although he’s studying again, Shuwami worries about his future all the time.

“I haven’t progressed in any way. There are so many things I don’t know,” he says, sitting at a wooden desk in one of Shehu Sanda Kyarimi’s classrooms. A clutch of curious peers watches him from outside the room’s windows. “I’m already too old to learn.”

Students aren’t the only ones who have struggled to adjust to the new educational order. Boko Haram killed more than 600 teachers between 2009 and 2015. When Maiduguri’s schools began to reopen, many instructors did not want to stand before their classes, says Mallam Kaka Isa Mohammed, principal of Shehu Sanda Kyarimi. “They were scared of the students,” he explains. “Everyone came to school in fear of being shot.”

They’d heard stories of male students recruited by Boko Haram who targeted former teachers. Andy Bwala, 46, a physics teacher at Shehu Sanda Kyarimi, recalls being threatened by Boko Haram at his home. “We just want to tell you that we know you by your name and we know your house,” an anonymous caller told him. “Most of your students are our members, but you don’t know them.” Now there are days when only a few teachers show up at a time—leaving many students with little to do but hang around school, waiting out the clock until they can leave.

A “fear of the unknown” guides decision-making, says Sadu Mala, the principal of Shehu Garbai. Schools no longer hold morning assemblies in their courtyards because the students would be sitting ducks for Boko Haram. There are uniformed security guards at the front and back of Shehu Garbai, and Mala has an agreement with traders who hawk their goods nearby to keep an eye out for suspicious men. He lets students go at the end of the school day (1:00 p.m.) in groups—girls first, then boys—“to avoid overcrowding at the gate.”

If a bomb detonates in a large group, more people will die, Mala explains. It’s better not to risk a higher victim count.

Mala remembers the morning of March 18, 2013, when he heard that other schools were under attack. He waited under a neem tree near his school’s entrance, ready to place himself between hundreds of students and any Boko Haram boys who showed up. Luckily, none did—Shehu Garbai was spared. Mala’s anxiety, though, held fast. Today, if a car runs over a plastic bag and pops it, “the sound it makes, psychologically we are feeling like it’s a bomb,” he tells me.

At Shehu Sanda Kyarimi, Zara Bashir is also nervous. The teenager is painfully aware of how brutal the world can be. Boko Haram hasn’t just threatened her life and education: While schools were closed, militants attacked her neighborhood, killed her brother, and threatened her 70-year-old father.

“But we made a decision,” Bashir says, referring to the students around her. They’ve all passed the security checkpoint, with nothing suspicious found. “No matter what, we will not stop coming to school.”

Reporting for this article was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation through the Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Continue reading to Part II: The Run of their Lives