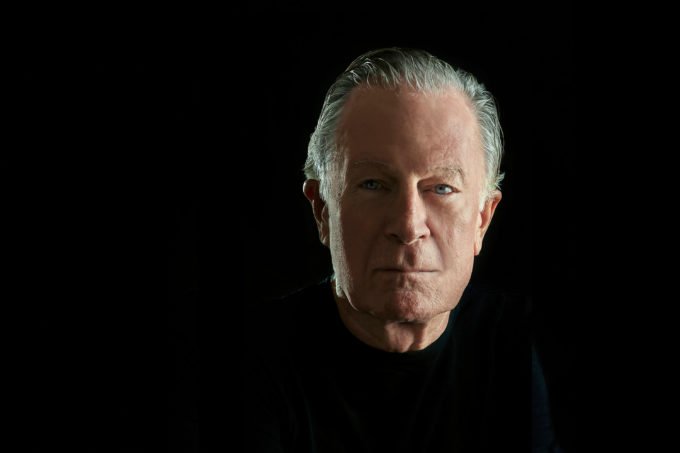

A Conversation with Jeremiah Tower

The star of The Last Magnificent on life at the beach, drinking with Russians, and what really happened to Stars.

Director Lydia Tenaglia’s excellent new film Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent looks at the life of one of the most pioneering and enigmatic chefs in U.S. culinary history. Before the documentary airs on CNN this Sunday, R&K co-founder Nathan Thornburgh spoke with Tower from his home in Mérida about Russian delicacies, learning to drink, and the foolproof kitchen equipment he can’t live without.

Nathan Thornburgh: Jeremiah, thank you for talking to us.

Jeremiah Tower: My pleasure. I was just reading Roads & Kingdoms this morning. I think it’s fabulous. Especially I was laughing over the Chinese camel milk mogul article.

NT: Ah yes, the famed Western Chinese hangover cure that wasn’t.

JT: You know, every region has some kind of white alcohol, all of which is poisonous. The one in Galicia, oh God.

NT: Yes, I know that one. Well, it’s an honor for little ol’ Roads & Kingdoms to be able to speak to someone who’s been around a lot of different places, a lot of different bad white liquors.

JT: That’s true (laughter).

NT: What has this been like for you to have your life up on the screen?

JT: I don’t know which is stranger, to have done it or to have to watch it. I think they’re both absurd. I hadn’t seen it until the day Lydia gave me a private showing the day before its premiere in New York. I didn’t even see it, I was so shocked watching myself on the screen. The next day it was in a big theater full of people and there was dead quiet for what seemed like 10 or 15 minutes. And I nudged Lydia, who was sitting next to me, and I was like ‘Lydia, we’ve gotta run for it, they hate this movie. Come on, let’s go.’ Somebody heard me say it and started to giggle, and then the whole theater burst out laughing. It got a big standing ovation at the end, it was wonderful.

NT: I can imagine without any feedback from the universe all the doubt might creep in for director and subject alike.

JT: Oh absolutely. I had not seen one second of it before so…

NT: Really.

JT: That was one of the conditions when I first talked to Lydia in San Francisco, she said she was going to do an hour-long interview and send it to CNN and see if they liked it. It turned into about a six-hour interview. But when we started I said, you know, I’ve got only two conditions: one that we take the high road with Alice Waters, and two that I have absolutely nothing to do with what’s in it or anything final. I don’t want to see it, I don’t want to know it. And she said well that’s interesting because those are the two things we were going to demand from you.

NT: What a dream for a director who needs to be able to tell your story in her way.

JT: Well I mean there was no point in doing it any other way. Full bore. Right between the eyes. Because otherwise, it would just be a fluff job, and not interesting.

NT: The film is astonishingly good, and at times very direct. I remember a specific challenge to the life you’ve built for yourself in Mexico after Stars, where someone says, “What is he doing, why isn’t he cooking? He stopped doing what he was meant to do in this life.”

JT: Yeah, that was Wolfgang [Puck].

NT: What do you think when you hear that?

JT: I think that if I had Wolfgang’s $50 million I would’ve headed to the beach a long time ago. You know? I can put that question back to him: When you’re that successful and you’ve got that much money you never have to work for another hour in your life, why are you working? Is that all your life is about? I mean, you should travel. Just read Roads & Kingdoms. Start at the beginning and just go.

NT: I love that. I have a thousand-story itinerary for him.

JT: It’s like: is your life Beverly Hills? Just think, you could be out in the middle of the Chinese desert, hungover on baijiu.

NT: Did other people say to you, you’re a man of luxury and attainment, why did you walk away?

JT: Merida [Mexico] is a very spiritual and very artistic place and I picked up on that the first time I saw it. Also, I had had enough of earthquakes, terrorists, hurricanes… I’d had enough of that for a while. So I just went to the beach.

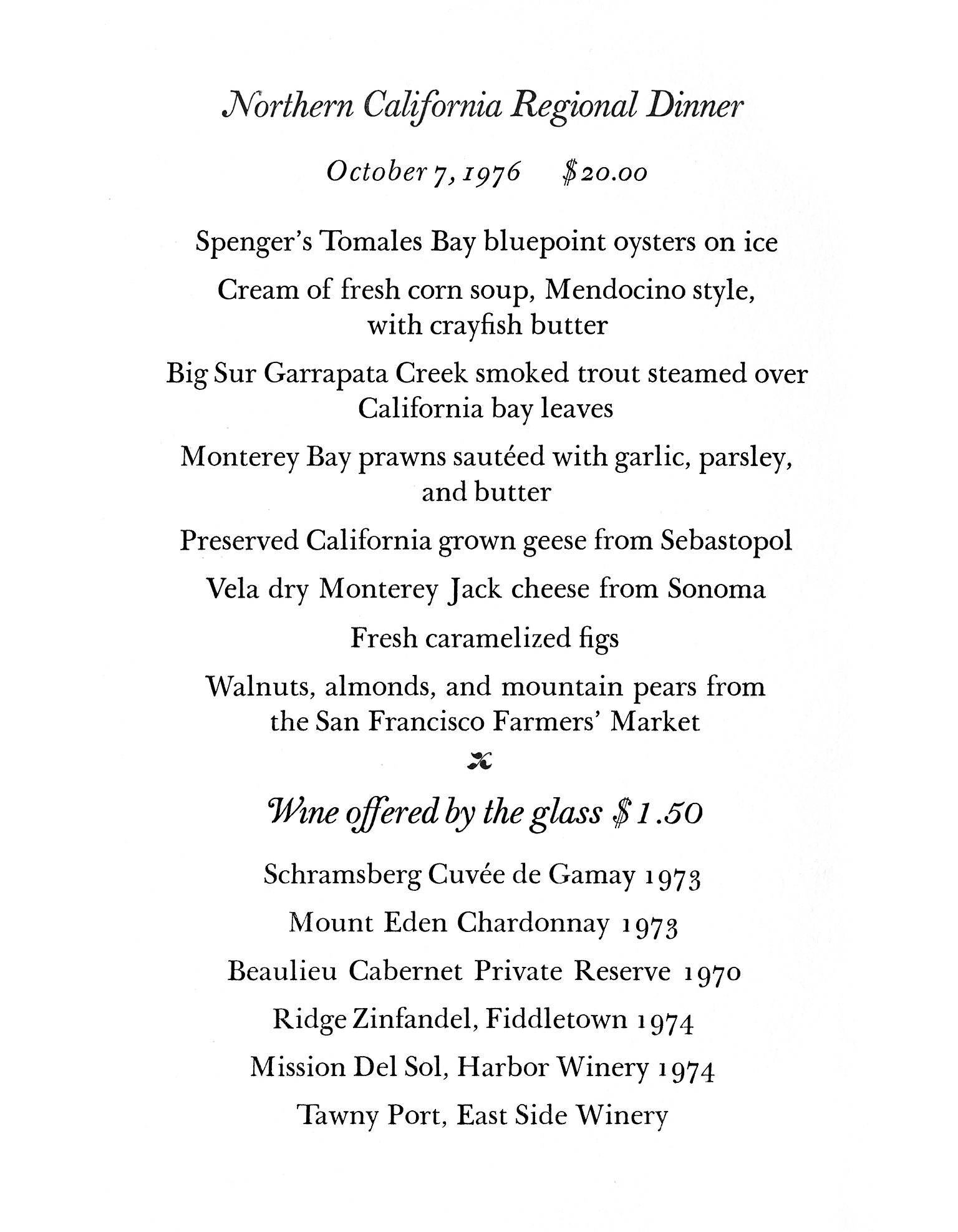

NT: At the beginning of your career, what were some of the dishes that for you made that connection between being a home cook and being a professional cook?

JT: I think actually the dishes I was cooking in college were much more adventurous because I was exploring. I was trying to cook my way through Julia’s first book, Every Dish, and then I had historical cookbooks that I was cooking. I was cooking a lot of things in the beginning in a little restaurant—it was just myself and Willy Bishop cooking—but when I made the first coulibiac, which I used to make when I was in college, that evening at Chez Panisse I thought, ok all the dots have been connected. And of course, no one who had ever cooked for me had ever seen a coulibiac, and I served it with frozen vodka and lots of sour cream and butter and everyone adored it, so I did it once a month from there on in.

NT: This is the baked salmon pastry?

JT: Yes. I did my version of it; salmon and mushrooms and rice, absolutely delicious—and then you pour melted butter and sour cream all over it.

NT: My grandmother used to cook coulibiac. There’s really nothing quite like it somehow.

JT: It’s unique.

NT: And this dish comes from your uncle?

JT: Yes, a Russian uncle. I couldn’t wait to try it as soon as I got back to college senior year because we had a house with a kitchen. But you know every cuisine has a turnover, a Cornish pasty, a whatever. It was originally the food you put in your knapsack when you went out into the field and you ate it cold for lunch. Coulibiac takes that tradition and puts it right up in the royal court. I love that.

NT: Lydia said I needed to ask you about your uncle, who didn’t make it into the film. Tell me about him.

JT: My aunt from high society Philadelphia met the young Russian who, when he was 18, commandeered a destroyer from the Russian Navy. He led his cadets at the age of 18—all of the officers had been shot—and he took them and captured the destroyer and sailed it to India and he presented it to the Americans, who said we don’t know what to do about you because we don’t know who we’re supporting. So he found his way to the United States, to Boston, not speaking a word of English. And he worked his way through MIT, learning English at the same time.

NT: My goodness.

JT: He designed the first jet helicopter to ever be able to take off. He was McDonnell’s partner in McDonnell Aircraft. And, of course, he was Russian, and he knew all these amazing Russians. I met [nobleman and alleged Rasputin assassin Felix] Yusupov’s childhood friend, for god’s sake, at lunch.

NT: Huh. Just men who casually lunch together.

JT: None of them had any money, of course, except for my uncle. So they’d all come to his apartment in Washington and every once in a while I was invited, as long as I was quiet. And it was at one of those lunches when they were talking about the time when Yusupov was at a dinner or lunch or something at a club with his mates, and the question of what was truly decadent came up, and everyone had their own version. Finally, Yusupov said, my dear, the only truly decadent thing is to drink Château d’Yquem and eat roast beef. So of course, I raced back to Cambridge and cooked that for my friends. And then I did it as a night at Chez Panisse which became sort of a legendary evening, so that’s how it all started and evolved.

NT: Your desire to find a golden strand from some conversation that’s happening on the outskirts of the social company of your aunt’s husband, and to race back home and build a new tradition out of it, first in college and then in the West—if there is a more classic story of your great talent, I’m not sure I’ve heard it. Do you have other stories of Russian cooking or Russian dishes?

JT: Well, for Orthodox Easter, all the Russians would get together and go to my uncle’s apartment because he was the only one who could afford the food and booze. One time, my uncle said, we should really get two or three of your best friends from Harvard and invite them down on the train. I knew what they were getting in for and I warned them, get some sleep, because this is gonna be a rite of passage. And he put them through all the vodka and then wonderful white wines and red wines and then he had a bottle of pre-Second World War something or other, and then he made them drink something to settle their stomachs—absinthe and soda. Well, of course, they nearly died, but they still talk about it.

NT: I can imagine. So the training was how to combine industrial quantities of fine Eastern alcohols and these heavy dishes.

JT: The point was that you couldn’t leave the table under any condition. I don’t care what state you are in at the end of the evening, but you have to stay at the table until the end, because that was true discipline and Old World manners. You knew you were dying, but you would never let anyone know. I’d been there a couple of times so I already knew what the sport was.

The 1989 earthquake cost me about $8 million dollars

NT: It was interesting in the movie to see the idea floated that the 1989 San Francisco earthquake shut down your legendary restaurant Stars. Was that the case?

JT: It’s told dramatically. The earthquake did ruin Stars, but not the event itself. We lost four bottles of booze off the bar or something, you know, that was it. But was most of the buildings in the Civic Center were damaged, and so they were boarded up and some of them shut down. The ballet and symphony and city hall and the courts and such, they kept going even though the buildings were condemned. They kept going for a couple of years, and then the civic center shut down, and as Michael, one of the people in the film said, Marc Francis, my chef de cuisine, one day was doing 325 lunches and the next day was doing none whatsoever. It was so bad that with all the massive construction trucks, somedays the suppliers couldn’t even get to Stars to deliver food. That earthquake cost me about $8 million dollars.

NT: My goodness.

JT: But then we did reopen. This is the long story, and the real one. We did reopen and it was fabulous again, and then I sold it in 1998 and it ran for two more years without me, with a new owner.

NT: What are you cooking now in Merida? And is there a piece of kitchen equipment you rely on?

JT: Well, you know the ingredients here are fish, pig, and chicken. The pig I leave to the locals because they turn it into cochinita and lechón, which make the most fabulous tacos in the world. So I don’t cook that much, I just go to the market every other morning, the main market, and pick up freshly shelled white beans when they’re in season, like right now, and morcilla, the blood sausage. This morning I had tacos and blood sausage.

As for equipment, there is no piece of equipment that is more versatile and wonderful and fool-proof than a live-fuel pizza oven. Now that’s impractical for everyone else, but if you do have a garden or terrace or something you can have one. You just put a big roast with lots of vegetables into the bread oven, go away, drink far too much, come back, and it’s perfect. It’s like a tagine, the Moroccan cooking utensil: you cannot go wrong. It won’t let you go wrong. I don’t know what the mystery is about a tagine, but that’s true.

NT: So there’s the film and you’re working on a book (Flavors of Taste, digital release scheduled for 2018). And what’s this rumor of you and [Mario] Batali and more restaurants?

JT: Oh, you know, that was after a week with Anthony [Bourdain] in New York and I got so tired of people saying, “well what are you doing next? Are you doing another restaurant?” So I finally just made that up. And Mario, of course, you know, is more perfect at PR than I am, so he said, ‘Of course it’s true.’ I think it blindsided him but he just said yes, of course.

NT: But what is actually next for you?

JT: I want to go diving and then figure out if it’s time for the next phase. You know I haven’t got that much time left so I want it to be spectacular.

NT: I really appreciate the time, Jeremiah. It’s very meaningful to me. Thank you.

JT: Likewise, to have someone like you on the other end of the phone is a privilege.

NT: Let’s meet in Western China sometime.

JT: [laughs] Sure. As long as we don’t have to drink that shit.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.