Two buildings in the Liberian capital reflect the country’s struggle to confront a history of violence, greed, and foreign interference.

Monrovia’s battered appearance belies its status as the capital of Africa’s oldest republic. The city center, a peninsula that stretches into the Atlantic with the Mesurado River at its rear, is defined by crumbling three story buildings disfigured by war and worn from relentless tropical rains. They line streets—named after white American men who have been dead for nearly two centuries—teeming with small time traders.

A handful of derelict structures, casualties of the 1989-2003 war, hint at remnants of grandeur. The most iconic is perhaps the abandoned Ducor Hotel, situated atop Snapper Hill in a remote corner of the peninsula. There, foreign aid workers hand over a few dollars to private security guards to tour the shell of the once-grand building that served as the seat of the interim wartime government only two decades ago.

The Ducor may be the best known, but it is the centrally located E.J. Roye Memorial Building that looms largest—both literally and figuratively—over the city that is the lifeblood of Liberia. The E.J. Roye served as the headquarters of the True Whig Party (TWP), one of Africa’s oldest political parties. The TWP’s rule, unbroken for more than a century, began and ended violently, laying the groundwork for one of Africa’s most gruesome wars. The now vacant structure is a vivid reminder of the unequal foundations on which the nation was built and which continue to haunt Liberia’s post-war reconstruction. And the struggle to reclaim the crumbling building also encapsulates the myriad problems that continue to confront Liberia as it battles to emerge from a complex history of violence, greed, and foreign interference.

The E.J. Roye is nestled in one of the most historic quarters of the capital. It towers over the Mesurado River and Providence Island, where the first group of black American settlers landed in 1822. The settlers were funded by the American Colonization Society, a private American enterprise backed by the U.S. Congress.

The site is bounded by several of the country’s most venerable nineteenth century churches, the original executive mansion, and the national museum. It opened in 1965, enjoying a 15-year heyday until indigenous enlisted soldiers led by Samuel Doe staged a bloody coup in 1980. This nominally ended the settlers’ economic and political domination. Known internationally as ‘Americo-Liberian’ but derisively referred to as ‘Congo’ by locals, the descendants of the pioneers continue to exhibit an outsized influence on Liberian affairs.

One of the few post-war additions to Monrovia’s topography lies adjacent to the E.J. Roye. Curiously, the Central Bank of Liberia’s new purpose-built edifice looks exactly like its neighbor. For Emmanuel Bowier, a former minister of information under Doe who worked in the E.J. Roye as a TWP functionary in the 1970s, the design is emblematic of Liberia’s tortuous political and cultural trajectory.

Bowier, a prominent oral historian and ardent advocate of Liberian cultural heritage, says that “even though the new order condemned the old order, when it came time to build a national landmark of economic prosperity, they built an exact replica. The height is exactly the same. These buildings constitute our twin towers.” Indeed, unlike other African nations that have pursued cultural decolonization by removing monuments and changing geographic place names, the imprint of Liberia’s settlers remains strong—cities, statues, and schools all commemorate Americo-Liberians whose power set the standard to which the masses continue to aspire.

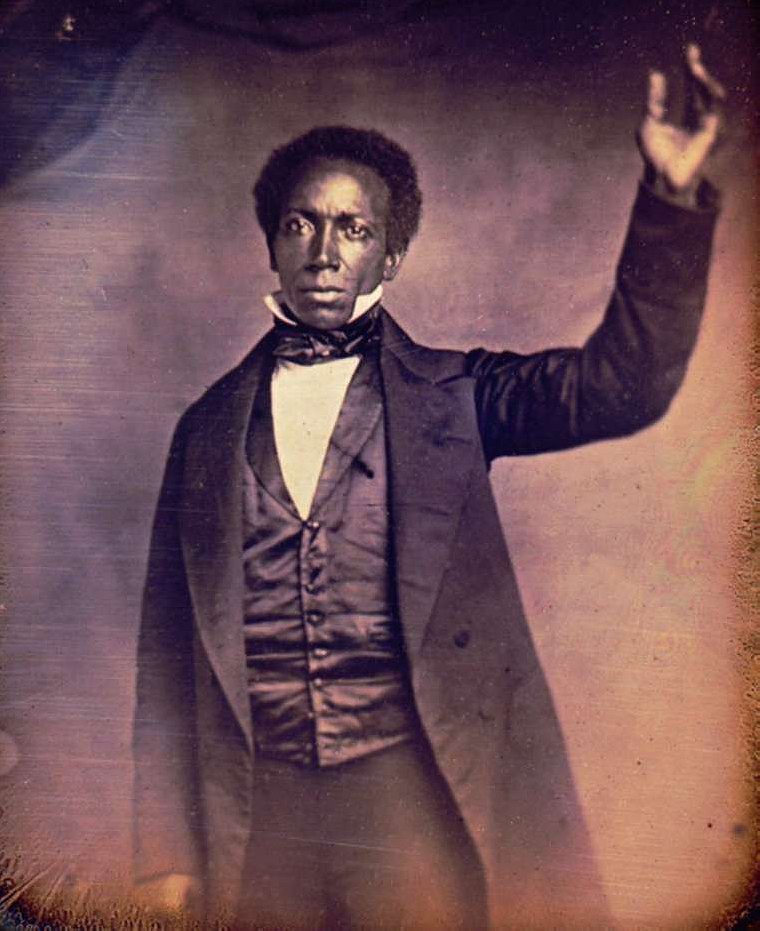

The story of the old order begins with the older building’s namesake, Edward James Roye, Liberia’s fifth president. An official pamphlet issued by the TWP notes that the party’s headquarters was constructed on the site where Roye was assassinated in 1872, amid mysterious circumstances several months after being removed from office following the negotiation of a controversial international loan.

Roye, who attended the University of Ohio in his native state before emigrating in 1846, was the TWP’s first national executive. A wealthy entrepreneur, he was supported by upriver farmers, frustrated by the domination of elitist coastal traders, who were often much lighter skinned and backed the Republican Party.

Roye’s fall from grace bears some resemblance to the travails of the current Liberian President, Harvard-trained Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who oversaw the construction of the new Central Bank. Although of indigenous extraction, Sirleaf assimilated into the settler class. She attended an elite high school next to the site of the future E.J. Roye building and was minister of finance when the last TWP government was overthrown.

A fellow minister in that government, Elwood Dunn, notes that Sirleaf has gone “to great lengths to spell out her own ethnic identity, distancing herself in the process from her settler-Liberian benefactors.” She came into office with much goodwill that has since been eroded amid allegations of corruption, nepotism (her son is a Central Bank governor), and a perceived penchant for indecision.

Roye’s contentious legacy was rehabilitated by President William Tubman, who governed from 1944 to 1971 and was Africa’s first president for life. Not only does the E.J. Roye structure face the Central Bank, but Roye remains economically relevant; his visage adorns the $5 Liberty note, the smallest denomination of the local currency (three of the five heads of state on Liberian bank notes were violently removed from office and murdered).

The highly influential Freemasons laid the cornerstone for the E.J. Roye on land originally owned by Gabriel Moore, one of the founders of the masonic craft in Liberia in 1867. The structure was designed by the local architectural firm, Milton and Richards. Richards is deceased, but his partner, Aaron Milton, who trained at MIT and Howard University, continues to conduct business from a dusty office despite being confined to a wheelchair.

Milton notes that the building was designed as an office building and entertainment center, and that it is home to the largest auditorium in the nation. In its heyday, it witnessed performances by international acts like James Brown, Mahalia Jackson, and Mariam Makeba. It was where Liberians attended graduation ceremonies, talent competitions, and traditional performances. The building housed some of Monrovia’s smarter restaurants, as well as the West Africa Rice Development Association, its primary tenant.

The E.J. Roye continues to showcase Liberia’s cultural heritage: Its front entrance features decorative concrete slabs showcasing political motifs that combine settler and indigenous designs. The work constitutes a lasting tribute to its creator, Vahnjah Richards (Winston’s brother), a Liberian educated at the Maryland Institute College of Art who was killed during the war.

Like many of Milton’s works, the 50-year-old E.J. Roye building only saw productive use for about two decades. It’s most recent practical application came at the end of the war in 2003, when the government deployed snipers to take advantage of its commanding heights and prevent rebels from crossing the Mesurado River.

Banned during the Doe years (1980-1990), the TWP claims that the interim wartime government of David Kpormakpor (1994-1995) decreed that its headquarters should be returned to its possession.

The TWP only formally reconstituted on the eve of the first post-war elections in 2005, under the leadership of Peter Vuku, a civil servant with no historical connections to the party.

The reconstituted TWP sought to capitalize on the E.J. Roye, its greatest asset. Around the time President Sirleaf assumed office in 2006, the party leased the building to a local outfit known as Westgate Management Realty. Westgate spent about $200,000 to rehabilitate the building before the Sirleaf government, eager to burnish its populist credentials, challenged the TWP’s ownership. Winston Tolbert, a key Westgate financier and the son of William Tolbert, the last TWP President, is pessimistic about the building’s future.

Tolbert notes that the former TWP Secretary-General, Clarence Simpson, in face-saving testimony before Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, urged the government to take possession of the structure as the TWP involuntarily deducted the salary of civil servants to fund its construction. The Westgate realtor doubts that the building will ever “be rehabilitated peacefully.”

An official touring permit of the E.J. Roye is $50.

In April 2013, the TWP entered into a memorandum of understanding with the ministers of finance, justice, and internal affairs that obligated the government to pay $225,000 (its leadership notes that in the 1990s the building was appraised at $13 million) to the TWP “in the spirit of national reconciliation” in return for vacating the building. According to the TWP’s current chair, Reginald Goodridge, the brash head of Liberia’s General Services Agency, Mayor Broh, then oversaw a team that sealed off access to the building, tore down the TWP sign, and harassed several squatters that the TWP had allowed to remain on the property.

One of the squatters, an elderly man named Pewee who served as a UN peacekeeper in the Congo in the 1960s, is the primary gatekeeper for access to the E.J. Roye. Eager to avoid additional confrontations with the state, he refers foreign visitors to the tourism office within the Ministry of Information, where the going rate for an “official touring permit” of the E.J. Roye is $50 with an optional guide available for $25 extra.

Goodridge, the nephew of a former TWP chair during the 1970s, sued the government and the Vuku leadership of the TWP as a “concerned partisan” seeking to retain the party’s historic headquarters. In the suit, Goodridge’s lawyers, Kemp & Associates, noted that Liberia’s Ministry of Justice was “vexatious, intimidating, and militaristic in nature and character” while engaging in “blatant attempt[s] to use scare tactics to take over the E.J. Roye building.”

Elected Chair of the TWP following an external mediation process that resulted in the party’s second post-war convention in 2015, Goodridge says that Italian, French, and Spanish investors have expressed interest in the E.J. Roye and that he would prefer a “long term lease agreement” for the party to maximize the building’s value. Meanwhile, Vuku, who remains influential in the party, notes that he favors “an amicable settlement with the government rather than going to court.”

In his inaugural address at the last TWP convention, Goodridge, citing the nation’s unique history, noted that “all of us in Liberia are still hurting from things in the past.” As the case of the E.J. Roye shows, the nation also remains mired in a fight over the spoils of the past, unable to pursue its few contemporary developments with an original twist.

Whatever the future may hold for the E.J. Roye, it seems unlikely to assume a role as the dignified elder statesman of Monrovia’s twin towers without a tortuous, expensive, and contested rehabilitation—just like the process the nation continues to face 36 years after the end of TWP rule, with a prominent former functionary of the TWP government still at its helm.

*CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story stated that Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s son was a former Central Bank governor. He is still serving as a Central Bank governor.