Remembering the era when Mexico’s music reigned supreme in the Balkans.

Marina de Ita had dreamed of travelling Europe for years. Her band, Polka Madre, was heavily influenced by Balkan and Roma folk music and, back in the late nineties in Mexico City, she’d fallen in love with the music of Goran Bregović. “I used to have parties in a clandestine bar in my house in 1998 and people went crazy for those tunes,” she says. “It came as a relief for many of us who were tired of rock and the music offered by Western countries.”

In 2015, her band was invited to play at the International Circus Festival in Mardin, Turkey, and de Ita seized the chance for a quick trip to the region she’d long wished to visit.

Once she arrived in Belgrade, she decided to make some money busking. “At first, I played some Finnish polkas and some from our Balkan-influenced repertoire, but nobody paid much attention,” she says. “They just threw a few coins.” Yet when she played Bésame Mucho, a seventy-year-old Mexican bolero, a small crowd gathered around her. Some sang along. “An old man became very emotional and even shed a few tears,” de Ita says.

The warm reception took her by surprise, but half a century ago, such songs dominated Yugoslav airwaves. As a Croatian friend’s mother recalls, “It was always Mexican songs and Bollywood films.” Serbian music journalist Dragan Kremer agrees. “For a short period, it seemed showbiz here was dominated by Mexicans and their local reps.”

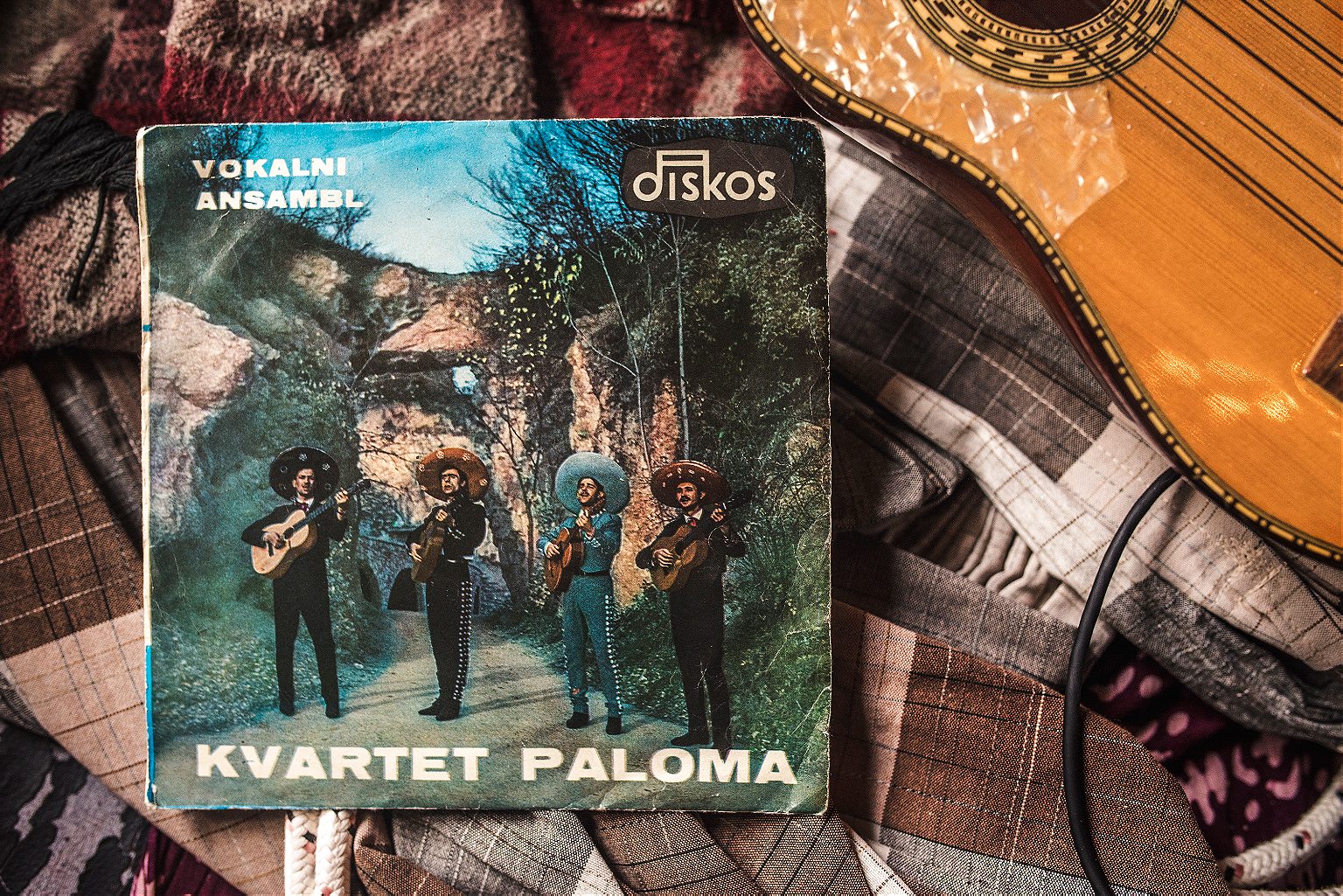

Explore the many shelves in Belgrade’s Yugovinyl store today and you can quickly amass a pile of ‘Yu-Mex’ records. The faded photographs on their sleeves depict men with names like Ljubomir Milić and Đorđe Masalović, proudly wearing sombreros and glittering charro suits. On the turntable, these records sound straight out of Guadalajara, except that the lyrics are in Serbo-Croat. For the Mexicans that ruled the radios here were, in fact, Yugoslav.

In director Miha Mazzini’s documentary Yu-Mex, Rade Teodosiljević remembers how his band Trio Paloma would drive from one gig to another, switching between radio stations in the car. “It’s hard to believe,” he says, “but we would drive for two hours or more and all the radio stations played nothing but our songs.” Croatian avant-garde poet Boro Pavlović penned lyrics for a track called Sombrero, and hits such as Kafu Mi Draga Ispeciswept across the nation.

In the early days of dictator Josip Broz Tito’s Communist rule, singing the wrong song could land you in jail. So how was it that mariachi gained such a following on the other side of the world, in a land separated by both language and the Atlantic Ocean?

Post-war Yugoslavia was, according to American diplomats in Belgrade, the “staunchest and most militant of all the Soviet satellite states.” Between 1945 and 1949, a total of 557 Soviet films were screened. British, French and American cinema were, however, considered tasteless. “Jazz, in my opinion, is not music,” decried Tito. “It is a racket!” Milovan Đilas, the Head of the Yugoslav Communist Party, declared America “our sworn enemy, and jazz, likewise, as [its] product.”

At the same time, however, tensions between Stalin and Tito were running high. As Stalin increasingly exploited Yugoslavia’s economy, Tito was looking to build a Balkan Federation with neighboring Albania and Bulgaria. When Stalin summoned the Yugoslav leader to Moscow to discuss the matter, Tito called in sick. On June 28, 1948, the Communist Information Bureau—the Soviet-dominated group in charge of coordinating with governments throughout the Eastern Bloc, better known as the Cominform—officially expelled Yugoslavia from its ranks.

Within a year, all films carrying Soviet propagandist messages were banned. Russian literature, once translated into Serbo-Croat en masse, was now deemed “a harmful waste of paper.” With the sudden shortage of Soviet imports and little arriving from the West, a cultural void opened up.

Popular legend has it that when the Yugoslav Agitprop department convened to discuss the matter, deputy head of state Moša Pijade thought of Mexico. Like Yugoslavia, it was a country of ‘workers and peasants’ living under a one-party system with a proud revolutionary past. It was also exotic and politically neutral. And while celluloid had grown hard to come by in the warring nations, Mexico’s cinema was experiencing a Golden Age. Not that there were many options. “Its import coincided with a lack of competitive stuff,” says Kremer.

“My parents like popular music, owned a gramophone, and had a decent varied collection of vinyl singles, including dozens of ‘our Mexicans’,” says Kremer. As a boy in the late 60s, his family would go to live concerts by the groups along the Dalmatian Coast. “It was always colorful, lively experience,” he says.

Another vehicle for the era’s Mexican music obsession were imported films. One beloved example is the 1950 melodrama Un Día de Vida, directed by Palme d’Or winner Emilio Fernández. A flop back in Mexico, it had played for less than a week before falling into obscurity, the original reels lost in a fire. Yet as Jedan Dan Života, it screened some 200 times in Zagreb and as often as four times a day for two decades in Belgrade. The only copy in existence today resides in the Yugoslav Film Archive, complete with Serbo-Croat subtitles.

On YouTube, it has found a second life among people like Zora Novak, who remembers crying when she saw the film in Zagreb as a teenager in the 1960s. “This film was very near to the heart of Yugoslav people who were themselves not so long back fighting for freedom in World War Two,” she says. “I didn’t forget this film and music even after 50 years.”

The film tells the tragic tale of Colonel Reyes, awaiting the firing squad for his role in Mexico’s bloody ten-year revolution but whose captor turns out to be his childhood best friend, General Gómez. In his youth, Gómez would sing the folk song Las Mañanitas to Reyes’ mother each year on her birthday. Sure enough, the two men appear before her in the film’s finale and, accompanied by a full mariachi band, Gómez serenades his condemned friend’s mother one final time. Nary a dry eye is left in the room.

Retitled as Mama Huanita and translated into Serbo-Croat, the song quickly became a Yugoslav favorite and a staple at birthday parties. “I remember how I used to sing from the heart when the melody was on the radio,” says Novak. Seventy years after the film’s release, when Marina de Ita was travelling the Balkans, she says that wherever she went, she heard the song. “When I said that I’m Mexican, they sang Las Mañanitas to me,” she says.

The crossover appeal is not hard to see. In one particularly drawn-out scene, Mama Juanita gives a visiting journalist a tour of her living room, replete with portraits of her late husband and four sons, all of whom met grisly and noble ends in the revolution. This melodrama was similar to the popular “partisan films” in post-war Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav Partisans, under Tito, were one of the only military forces to liberate their own country from the Nazis, and were a fundamental pillar of the country’s cultural heritage. Partisan films became a genre in their own right; although a form of propaganda, they’re not overtly political and are more similar to the campy thrillers that came out of Hollywood and the U.K. during the same period. An estimated 1.8 million Yugoslavs died in the war; almost every family had lost a loved one. When Un Día de Vida and its soundtrack arrived, such memories still loomed large.

By the eighties, however, Tito was dead, Yugoslavia was competing in the Eurovision Song Contest, and Dire Straits and Eddy Grant were performing in Belgrade. Yu-Mex was relegated to history. “Much later, in the mid-80s,” says Kremer, “I was surprised how some of these bands were still surviving in provinces of Yugoslavia, playing in kafanas—loosely, the Balkan equivalent of the bar circuit.”

The genre is a curio lost in time

Today, the genre is a curio lost in time, living on mostly in small online fan forums or in piles of old records at local markets. But a few holdouts remain. Zagreb-based Mariachi Los Caballeros has, over the past eighteen years, toured internationally, performing live with Los Lobos and famed operatic tenor Ramón Vargas. Naturally, their repertoire includes Las Mañanitas. “The post-war period of the 1950s was a very fertile ground for Mexican revolutionary songs, with which many identified,” says trumpeter Franjo Vinković. Not only are the genre’s cadences similar to Dalmatian folk music, he says, but “many composers from Dalmatia in the 70s and later began to include certain segments of Mexican compositions in new songs that they composed.”

Like Marina de Ita, Bruno Bartra—who performs under the name DJ Sultán Balkanero—also identified with Balkan genres from his home in Mexico. When Goran Bregović toured Mexico in 2008, the young DJ had the opportunity to meet him. “He told me that he had been an ardent fan of mariachi music in his youth,” he says. “He told me that in Yugoslavia, mariachi music was very popular. This has been fascinating for me; I’ve started listening to some Yugoslav mariachi.”

The distinctive “oompah” sounds of Balkan brass date back half a millennium to the mehter bands who marched into battle with Ottoman janissaries. The Roma, meanwhile, had fled India for Europe, incorporating local melodies and instruments as they went, eventually arriving on the Balkan peninsula. This heady mix ultimately arrived in Mexico via the Spanish, where it morphed and mixed into the mariachi music we know today.

“A friend who visited Serbia told me that he brought examples of Mexican wind music,” says Polka Madre’s Carlos Toledo. “Serbs told him, ‘that’s our music.’ He had to correct them, ‘No, that’s Mexican music.’ There are bands like that in our country that at times would be very difficult to distinguish from a group of Balkan musicians.” Indeed, when Polka Madre performed in Mardin, he says locals told him, “This sounds and tastes like here, but with a twist.”

Top image: Polka Madre. Photo by Alexandra Mck.