A film-maker’s snaps of a lavish wedding in Western Sahara confound stereotypes of one of Africa’s most poorly understood regions.

Dakhla juts out into the Atlantic, a windblown peninsula at the western edge of the Sahara. Until recently, the few people who wanted to make their way to this desert outpost had to travel by bus from Morocco, over interminable flatlands and through multiple military checkpoints

Today, a direct flight connects Casablanca and Dakhla, further contracting our world and strengthening Morocco’s grip on Western Sahara, a region it has occupied since 1976. Swiss windsurfers are welcome in what is known as “Africa’s last colony,” but journalists are not.

We arrived in Dakhla as guests of Salmou “Doueh” Baamar, a music vendor, electronics repairer, and family man widely considered the greatest musician in Western Sahara. He was hosting a massive wedding celebration for his eldest daughter, Oulaya, and we were there to make a film about it.

Over 500 guests were on their way, traveling along a new highway cut through the desert from Mauritania. Hundreds of chickens, dozens of goats, and at least one camel would lose their lives. A tent the size of a city block went up in a Dakhla square.

Doueh and his wife, Halima, are the leaders of the legendary family band Group Doueh. Their music is a mix of Sahrawi classical sounds and the electric distortion of the Jimi Hendrix tapes they grew up on. To achieve this, Doueh added pickups to a tidinit, the stringed lute common throughout the region. He plays his homemade hybrid instrument through distortion and phase pedals. Combined with Halima’s powerful voice and a relentless percussion section comprised of friends and family, this unique sound, blasted at top volume at weddings and parties throughout Western Sahara, has made them the most popular band in the region.

My friend Hisham Mayet heard an early Doueh track more than a decade ago on the radio in Morocco. There was no artist information, and local cassette vendors could only tell him the music came from the Sahrawis in the south. Obsessed, Hisham traveled through the desert to find the source. In Dakhla, he was led to Doueh’s cassette shop. He played his radio recording and Doueh laughed: “That’s me!” Four albums and multiple international tours later, Hisham has become family.

As famous entertainers, Doueh and Halima consider it a duty to host the biggest wedding Dakhla has ever seen. For a week in July, we filmed the preparation, daily life, and wedding itself: three days and nights of music, food, and dancing. Like all guests in Sahrawi homes, we were greeted without reservation or judgment.

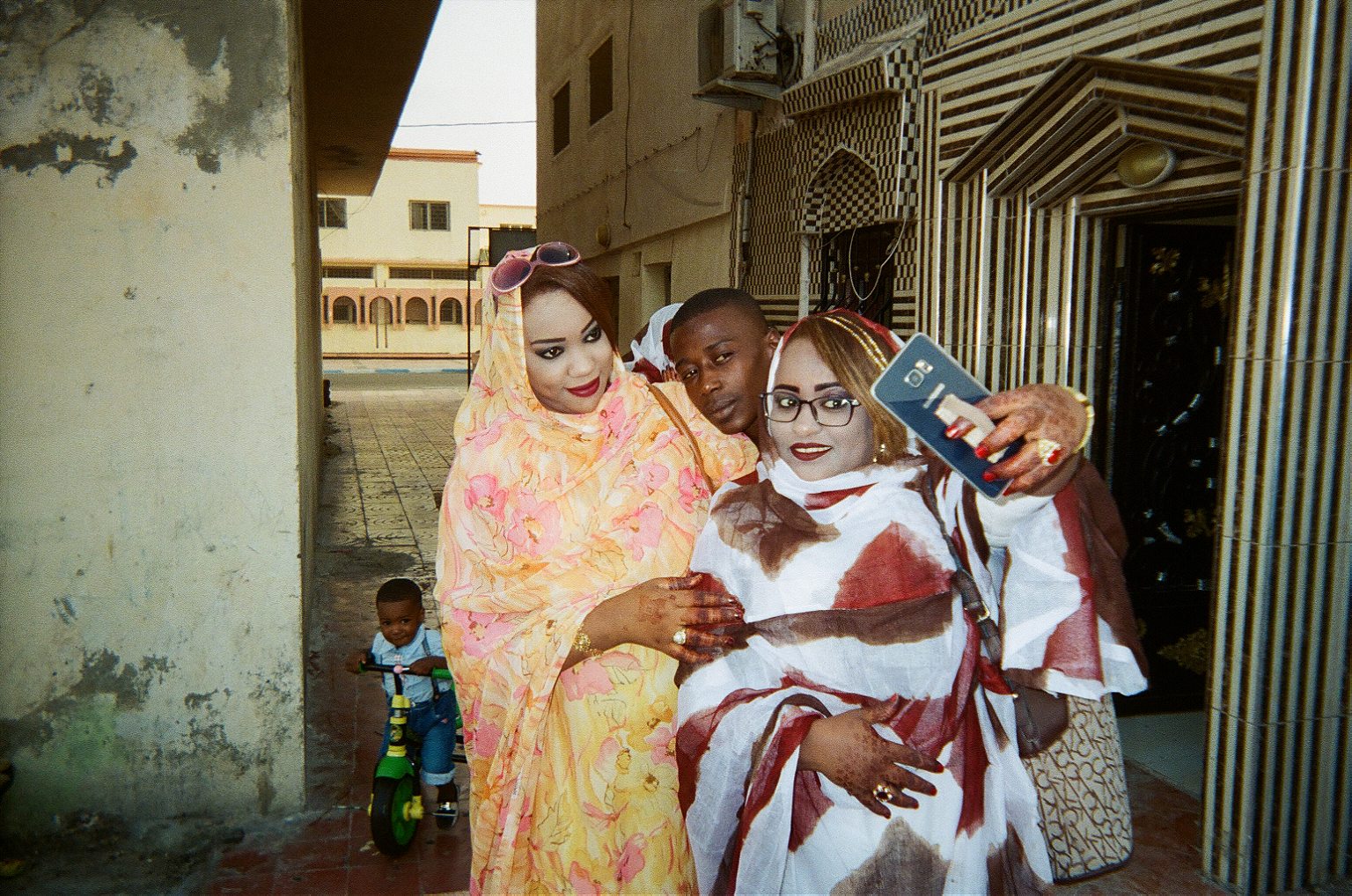

I picked up a disposable camera at a gift shop somewhere on the way to Dakhla. I wanted to use it to catch different perspectives and quiet moments during my downtime from filming. I worried our cameras would be intrusive, but the wedding finery was out in full force, and everyone was eager to pose.

Doueh’s world is one of deep religious devotion punctuated by bright colors, constant music, and comfortable interactions between men and women. Despite my Iranian background and my work throughout the Middle East, I had never come across this style of Islam. Halima ran the show, constantly on her phone, controlling the money and movement of this huge operation.

As artists, Doueh and his family are even more inclusive than most. Their compound serves as a sort of social free-zone. These disposable camera photos are a small glimpse into an exuberant, colorful, and artistic celebration that confounds most stereotypes about the religion and the region. It’s a feeling we hope to expand on in our forthcoming film about Oulaya’s wedding in the Western Sahara.