Photographing the Ugandan capital after the sun goes down.

There is one photo that Michele Sibiloni regrets taking out of his book just before it went to print: a selfie. The photographer says he was bored of seeing himself, all serious and wide-eyed, among his photos of Kampala. But he has since changed his mind.

“It was a mistake,” he told me last week in New York. “I think that it would have been good to show I was part of the story.” Even without the selfie, though, it’s not hard to imagine the wild adventures Sibiloni experienced while working on Fuck It. And because the book contains very little information about what is happening and who appears in the pictures, flicking through it can sometimes feel like looking at your phone the morning after a night of heavy drinking. I met Sibiloni to try and piece together the story.

Roads & Kingdoms: When did you take the first picture for this project?

Michele Sibiloni: The project started with a picture I took in the first year that I was living in Kampala, in the end of 2010. Like many of my colleagues, I covered part of the Arab Spring at the time, as well as the war in Congo, and there was a period where I was in a bit of a crisis with photography because I was taking the same pictures as all the other photographers. So I started to look for a project that I could do that was more related to myself and to the life I was living, and the night is something that has always been a big part of my life.

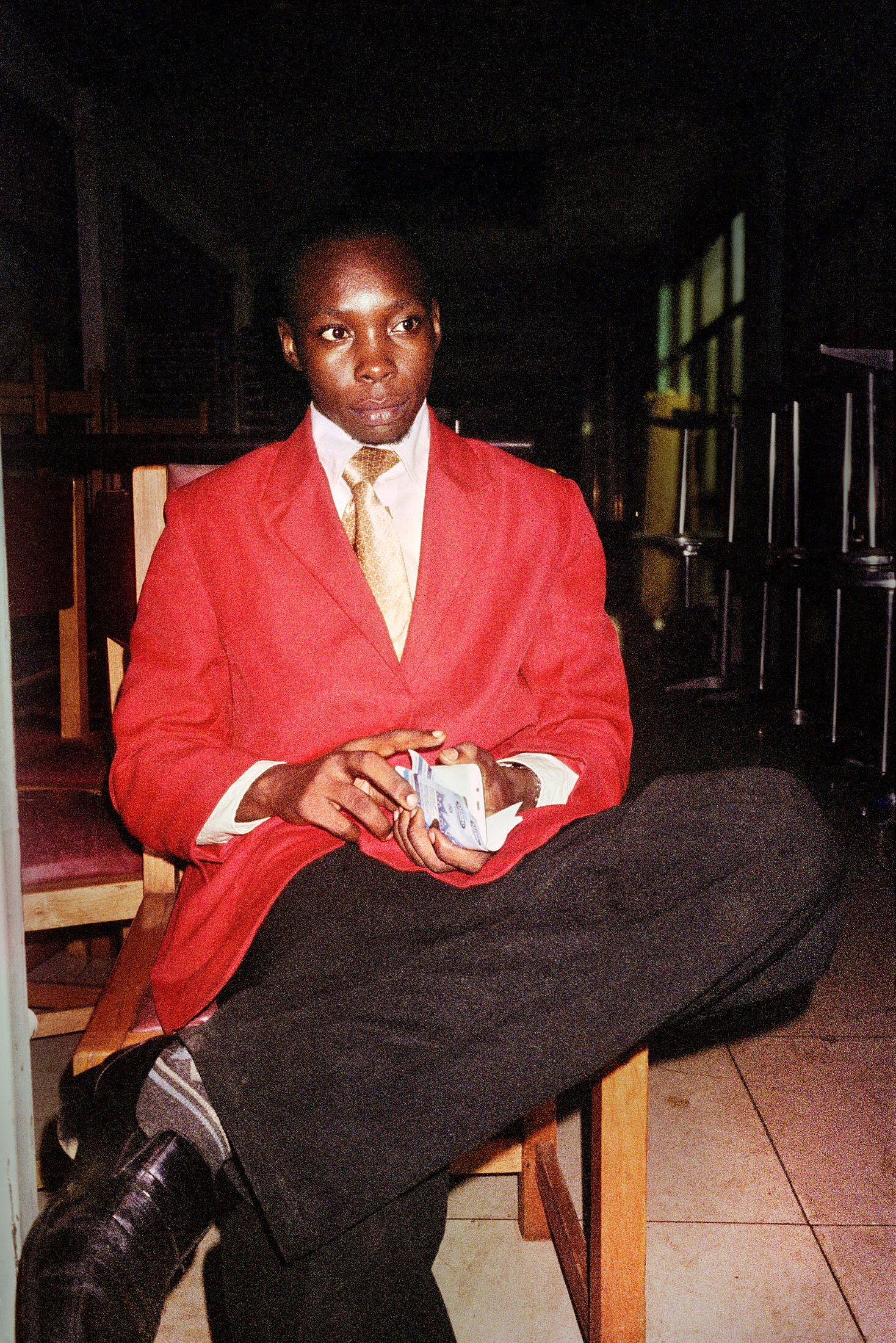

R&K: Who is the person in that photo?

Sibiloni: This is a night guard. In Uganda, there are private guards that you can hire to look after your shop or bank or whatever. Some of them have guns or different kinds of weapons, this one had a bow and arrow. First I decided to start a series of portraits of these night guards, and from there I felt like taking more portraits and spending more time photographing other things that were happening on the street at night. One thing led to another, and I decided to open the project to a sort of night adventure in Kampala based on my experience. It has sort of been an excuse to take pictures, to go out and to have encounters and explore the city.

R&K: So during the day you were on assignments and at night you did this?

Sibiloni: Yes, exactly. When I wasn’t very busy I was going out every day. I took it very seriously. Sometimes I would stay out until morning, sometimes it was just a walk or a couple of hours. When you do something every day, when you’re very committed, it’s something that pays off in the long term. It happened once that I went out and I took only two images even though I stayed out until five.

R&K: Were you alone most of the time?

Sibiloni: Sometimes I was alone, sometimes I was with a friend or two. It also happened that I went out with friends just to have fun, and I would snap a few pictures. Sometimes I was going out with a plan, like taking 10 portraits of night guards, and then other times I tried to explore a different part of the city I hadn’t been to before. I stopped and talked to people a lot, took phone numbers, gave my phone number to a lot of people who called me so we could meet again. It was kind of random.

R&K: That sounds pretty exhausting.

Sibiloni: Actually, I had quite a lot of energy at that time.

R&K: A lot of the people you photographed look drunk or unaware that there’s a camera around. How would you respond to people who think this is problematic?

Sibiloni: Not all of these people are drunk. I took photos at a boxing match, I took photos of a bouncer resting at the end of the night, I took photos of the Ugandan crane, the symbol of the country, of policemen. For me, the fact that there were so many things going on at night was really attractive. Not only in clubs and bars, but also people working, cooking, doing something on the side of the road. It’s completely different to where I come from, because I grew up in a quiet town in Emilia Romagna where there’s no one around at night. Everyone is locked in their houses and it’s just me and my dog walking around. So the fact that in Kampala you go out and you feel like there’s a lot of nightlife going on, that was really interesting to me and that’s what I photographed.

R&K: How did this project change your vision of the city?

Sibiloni: Kampala is quite unique because people mix pretty well. They are not separated in bars and in clubs, like maybe in Nairobi or Johannesburg. Of course, there are cheap places where people who have less will go, but it’s also easy for people to mix. And that’s something that makes your life better. You have a freedom in that city that you don’t have in many other African cities. For example, in Kigali, you are not allowed to play loud music, you’re not allowed to drink in the street or do a lot of things. This freedom that you have at night in Uganda is the opposite of what you have during the day: a religious and conservative society. There are these evangelical churches that are pushing anti-gay bills and morality laws, which politicians also have on their agenda. But when you try to force people to behave in a certain way, you get the opposite. At night, people drop their masks and go wild.

R&K: What do you think the nightlife says about Uganda today?

Sibiloni: Today, you don’t have any political freedom in Uganda. You cannot gather 10 people and talk about politics. But you are free to go out and drink as much as you want. I’m not saying that people replace the lack of freedom with drinking and dancing, but it’s something that they can do to forget, and to just say: “fuck it.” Also, the president is quite old, so we don’t know how long he will be around and what will happen after. If there is a coup like the one in Burundi, the country could go back 20 years. For me, it was important to document what people are doing during this specific time period. Maybe in 10, 20 or 30 years, it will say a lot about what life was like at the time.

R&K: Do you have a favorite bar or club that you photographed for this project?

Sibiloni: Many images were shot in this neighborhood called Kabalagala, which is very close to where I live. People always stop me and ask for pictures; people trust me there. There was a bar called Tilapia where I took some of the pictures, which was owned by the guy who wrote the introduction to my book. His name is David Cecil and he was actually deported from Uganda because he made a play where the actors were interpreting gay characters. The officials advised him not to do it, but he did and they kicked him out. When he wrote the introduction he was in the U.K. and now he’s back. His bar was one of my favorite places.

R&K: When I look at these images, I see a lot of people partying but it also makes me really sad.

Sibiloni: Yes. During a night out, you have these peaks of fun and these peaks of depression, and so that’s why there are these two phases in the book. Life is not easy for a lot of the people I photographed. For some of them, the night is how they make a living. Even for expats, sometimes people living in that part of the world are here because they’re running away from something. Everyone has his own issues and that’s also present in the book.

R&K: What did they think when you showed them the book?

Sibiloni: Some people laughed a lot because they had never seen anything like it. These are the places they live in, where they spend time. But others didn’t like it because they thought I wasn’t showing the beauty of Uganda. They said I should have gone to high-end clubs and parties. They thought I was trying to portray Uganda, but I was not. I was portraying my experience there. I was going where I would have gone anyway. The book launch there was really nice, we had a party in the neighborhood where I had taken a lot of the pictures.

R&K: Why did you decide to shoot in both black and white and color?

Sibiloni: I did both because for me, the project was based on freedom. Sometimes I was running out of color film, so I shot in black and white, which I could develop myself so I could see the pictures immediately. For the color, I had to wait to go back to Europe to develop the film. And then when I had all the pictures I was like, damn, I got black and white and color, and I should have done one or the other. Then I just thought: let’s put it together, fuck it.

This article has been edited and condensed.