A Croatian photographer retraces the footsteps of a British writer in Yugoslavia to try to reassemble a country that no longer exists.

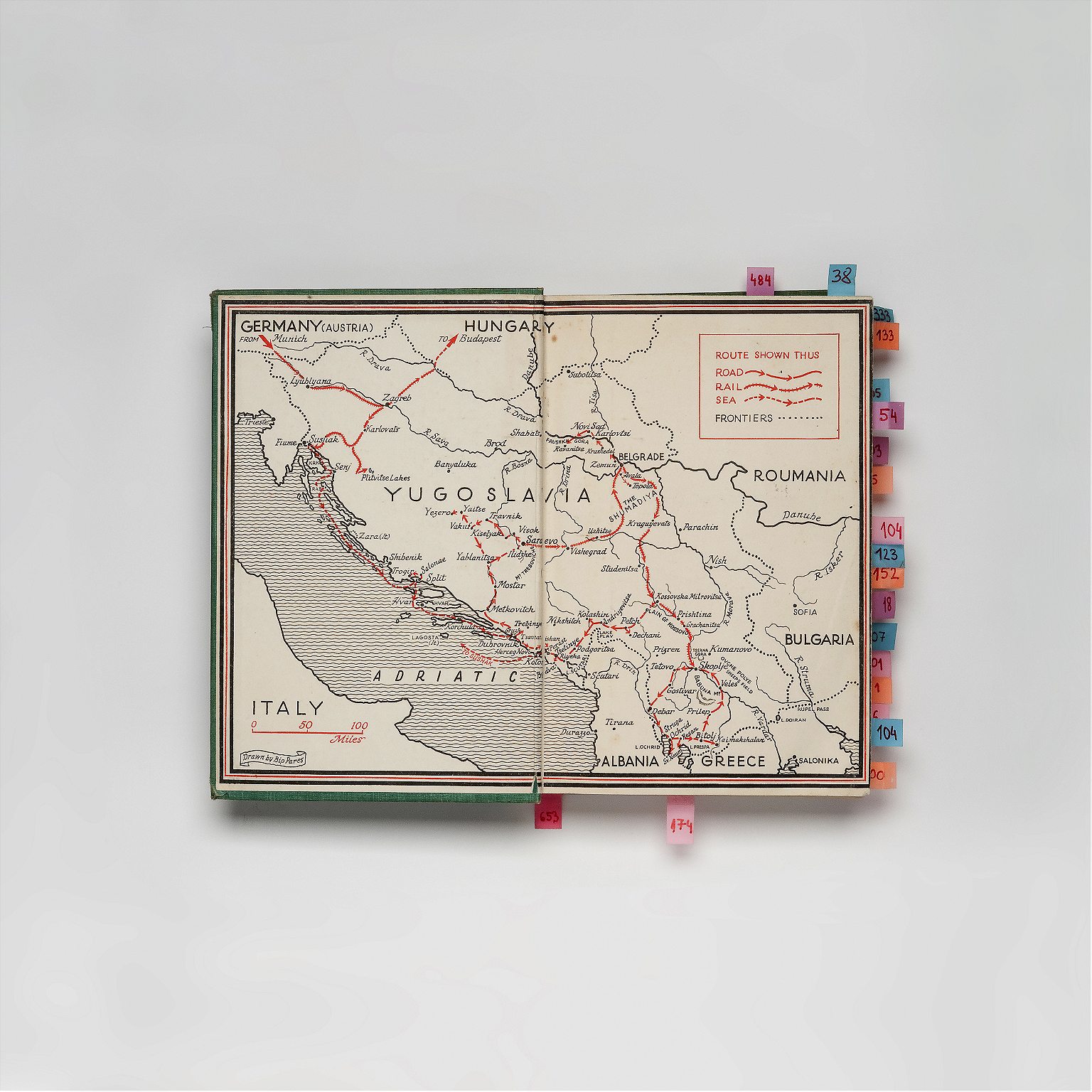

Eighty years ago, on Easter Monday in 1936, a writer named Rebecca West embarked on a journey throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It was the first of three trips that would make up the basis of her book, “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon,” an obsessively detailed chronicle of her wanderings and observations in a soon-to-be disappearing country. Decades later, the Croatian photographer Dragana Jurisic picked up the book when she moved from her home in ex-Yugoslavia to Dublin. It became a roadmap for her own examination into the country in which she was born, but which no longer exists. Part reportage, part memoir, “YU: The Lost Country” is her way of saying goodbye. She joined R&K from Dublin.

Roads & Kingdoms: You just came back from Sarajevo, can you tell us about your show there?

Dragana Jurisic: Yes, it’s the first time I’ve shown this work there. It’s not a regular gallery space, and I was working with such a constricted budget that I really needed to make a lot of allowances in the way things were presented, but it’s definitely good that people there can see it. Anyway, I don’t think this work will ever be shown in an institution in ex-Yugoslavia. They would not put funding into something that references what they have tried to obliterate. You know, the whole work is based on the idea of this forced amnesia among everyone—Serbs, Croats, Bosnians—they have all tried really hard to delete any memory that Yugoslavia ever existed.

R&K: How has the show been received so far?

Jurisic: There was an interview published in the liberal national newspaper Oslobođenje, and then I got an email from my dad and from my mother separately, telling me: how dare you say that the Croatian government is fascist? You don’t have to live there! Well, it is fascist, I was there through the 90s after the war, but I guess that because I live in Ireland now, I forget how you can get in trouble for saying stuff like that. I wasn’t considering my parents when I blurted that out, but I mean I stand behind it, it’s true.

R&K: You must be used to strong reactions to this work, since the book came out a few months ago.

Jurisic: I was very nervous when the book came out, but the feedback was positive. There was just this one article in a daily newspaper in Croatia by a political analyst who just went for it. But he never saw my book or my work, he was just using it to vent hatred basically. Also, Sean O’Hagan reviewed my book for the Guardian and the article was tweeted like 5-6,000 times, but there was no comments allowed. Usually in the Art and Design section there are comments, so when I met him later in Paris, I just thanked him for not allowing them. And he said that actually, they did allow comments for about an hour and then a shit-storm started and they closed them down. Anytime you have anything to do with ex-Yugoslavia, all these crazy nationalist idiots use it as a platform to vent hatred. With the Croatian article, I said to my dad: buy the print paper, do not go online. And of course he went online and he read all these horrible comments about his daughter. I’m 40 years old you know, but he was commenting back—in capital letters, because he’s like 70—and I was like please take everything down, it’s embarrassing. You don’t engage with crazy people.

R&K: Why did you decide to leave the region?

Jurisic: I grew up in Croatia and got a job as a psychologist straight out of college. But the politics in the 90s there were just absolutely abominable. I just couldn’t imagine myself living in this right-wing society, and you didn’t have to be very clever to figure out that this situation was not going away for the next 20 or 30 years. I couldn’t imagine wasting my life in this climate or bringing up a family or anything like that. So I decided to leave, I actually went to Prague first and there I met lots of runaways from the ex-Yugoslav Republics, but Prague was a crazy lifestyle that lasted for a year and I just wanted to find a place where I could speak English and could advance my career. Then, I visited some friends in Ireland and I really liked it.

R&K: Is that when you started photography?

Jurisic: I had to find a job first, so I ended up working at St John of God, one of the biggest psychiatric hospitals in Dublin. I worked there for eight years, with people with learning disabilities. But the whole this time I was going back to this book “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon” by Rebecca West. I read it for the first time when I arrived to Dublin because my boyfriend at the time was studying international relations and he told me I should read it. The book was fascinating, but it also made me angry because I thought she was over-romanticizing that whole region. I read it, I left it, and maybe three or four years later I went back to it. Every time I re-read it, I was like holy shit, how can this woman, a foreign woman who goes there on three relatively short journeys, nail down the essence of the place so well? I was thinking a lot about that and I started researching her life. She was Anglo-Irish but she never felt like she belonged to England or to Ireland. She always felt displaced. And when she goes to Yugoslavia in the 1930s, she feels that for the first time in her life, she has found a place where people are like her: they’re all displaced. She feels like she has finally found her motherland, and she has this prophetic moment where everything becomes clear to her: she sees the advent of the second World War, and she says the country is going to disappear.

R&K: Is that why she wanted to write about it in so much detail? To preserve its memory?

Jurisic: Exactly. And actually since she published her book in 1941, Yugoslavia disappeared twice, in 1941 and then in 1991. It really is a timeless book. I mean, people don’t walk around anymore in full costume, but the mannerisms she describes, the way people communicate, the essence of the place, it’s exactly the same. I think it was Geoff Dyer who once wrote that it was like a metaphysical Lonely Planet that never goes out of date. Lots of journalists in the 90s used this book as a guide.

R&K: Why do you think that initial read that made you angry?

Jurisic: I think I was just pissed off. I was angry that we allowed what happened to happen. I have a mixed background: a Serbian mother and a Croatian father, and I saw what these two sides were doing to each other, and I can definitely see what Croats and Serbs are doing to Muslims in Bosnia. Most of my father’s friends, who are liberal, intelligent people, were ignoring this at the time. It’s like it wasn’t happening. There was a concentration camp for women across the road from us on the Bosnian side, and everyone knew but no one said anything. It’s very scary actually, when you see that people can behave like total zombies.

R&K: Why did you choose to base your project on “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon” and not something more personal, like your family history?

Jurisic: I wanted to deal in some way with the loss of national identity and the loss of a country. The idea was to reassemble the country through my work. I wanted to make a metaphysical home where my identity could reside. But it didn’t turn out that way. It totally felt like a funeral procession. I was following a ghost on her travels through ex-Yugoslavia, and I think for me it was a way to say goodbye as well. I used this book because this whole region is so complicated historically that if I didn’t have a road map, I would have gotten totally lost. I don’t think this project would ever have ended. I needed a start date and an end date, and she basically tells you: I start on the Easter eve in Zagreb in Croatia, or I got up at 6 in the morning and I went to the market and I met these friends. I was able to recreate it almost to the hour. It was kind of nuts in a way because she’s a writer, and she would go to one place and take it in and then go somewhere else to write about it. So I would arrive somewhere she had spent 20 minutes in, and there was so much more there to see or photograph, but because I was really specific about being quite regimented in following this itinerary, I just kept moving as she moved. I remember in Skopje, she stayed for two weeks. After three days there, I was just like what am I doing here? It was challenging for a photographer to follow a writer in that way.

R&K: Do you think that by following Rebecca West’s footsteps you were trying to protect yourself and your family?

Jurisic: Yes, although I did expose them quite a bit anyway. My father is this crazy eccentric person who doesn’t give a crap, and sometimes I’m scared for his safety, for the stuff that he shares and talks about, but I feel especially bad for my mother, who is a Serb living in Croatia. She had so much trouble in the 90s because of what she was. I think I did kind of expose her, but she had her revenge on me. There was a radio documentary made about “YU: The Lost Country” called “Journey To Yu,” and it was shown at the Belgrade Festival last year. My mom came from Croatia to see it and she invited like half of the Orthodox Church at the screening. I was like do you know what this is about? Are you trying to get me killed? But everything went OK in the end.

R&K: What did they say?

Jurisic: Nothing. There was a lot of silence. I mean, I actually had to walk out of the screening 15 minutes in because I could literally see my heart beating in my chest. It was shown in Sarajevo this year and people there really enjoyed it. They were laughing at the right spots, because I guess we have this shared experience. In Serbia, even young people who acknowledge the fact that what happened happened still don’t want to engage emotionally with this responsibility or shame. I think that really, after the war, they should have done to all of us what they did to Germans after the Second World War. Total reprogramming. Showing what exactly happened.

R&K: How difficult was it to engage with people about Yugoslavia during the project?

Jurisic: For me, the toughest place was Kosovo, because that was the last place touched by the war. I was not welcome from any side. The Serbs didn’t trust me because I had a Croatian passport, and the Albanians didn’t trust me because my first name is very Serbian. Actually, one nice Albanian man came up to me in Pristina after he overhead me talking to my assistant and he said just do yourself a service and call each other different names. People have been beaten to death basically because they spoke in the wrong accent. So that for me, was a very difficult place. Overall though, either people didn’t engage in conversations about Yugoslavia, or if they did engage with me, they would be very nostalgic. They would tell me that 20 years later, the situation is worst than it has ever been. When the war ends, you have this optimism that things will get better, and they didn’t get better. The whole economic system there is falling apart.

R&K: What were the differences you found between the countries you traveled through?

Jurisic: This is total generalizing, but I think Rebecca West describes it a little bit when she goes to ex-Yugoslavia. She favors Bosnians the most and then Serbs, and she thinks Montenegrins are very handsome, but Croatians are a bit dry. I find that very funny. When we have family birthdays where both sides of my family are there, the Croats will be there, sitting, looking stern and smoking cigarettes and my Serbian cousins will be singing and crying. There is a slight difference in the temperament, but to me they’re all the same people.

R&K: And do they talk about Yugoslavia the same way?

Jurisic: Yes. There is a lot of nostalgia. But it’s also a time of sobering up now, and understanding the extent of the crimes. I think that people are slowly taking on responsibility. But when I talk to my friends back home, they’re very worried. Older people are coming to terms with what happened, but then you have this generation born post-war who is ultra-nationalist, basically fascist. Why would you hate Serbs or Muslims if you never had to live with them?

R&K: How many trips did you take around the region?

Jurisic: It was three trips, just like Rebecca West. And you know, it’s very interesting because she kept diaries very consistently throughout her life, but from this period of 1936 to 1942, I couldn’t find her diaries. They just disappeared. I was in contact with Yale Library and the University of Tulsa and they have everything before and after, but not the period in question. And then, there are all these stories that she might have worked for British intelligence. I don’t think she was Mata Hari, but probably anyone who traveled at that time would have been in some way reporting back, so she must have provided some information. Also, she never went back to Yugoslavia after the Second World War.

R&K: How present was she throughout the whole project?

Jurisic: I was reading so much about her at the time. I just find her fascinating. And I find that we are similar as women. We were going through a similar period in our lives: we were both in the second part of our 30s and many personal things also clicked, like she had some kind of operation and I did too. Things were weirdly overlapping. I think she had a miscarriage and I also had a miscarriage in between the two trips. There were lots of life events crossing.

R&K: Is she still a big part of your life today?

Jurisic: She is like a silent companion of my life, but now I have to move on. My new project is also very immersive, so I would like to jump all the way in. Sometimes you have to leave your old friends behind and go back to them later on.