Finding Your Breakfast Home Halfway Across the World

Finding Your Breakfast Home Halfway Across the World

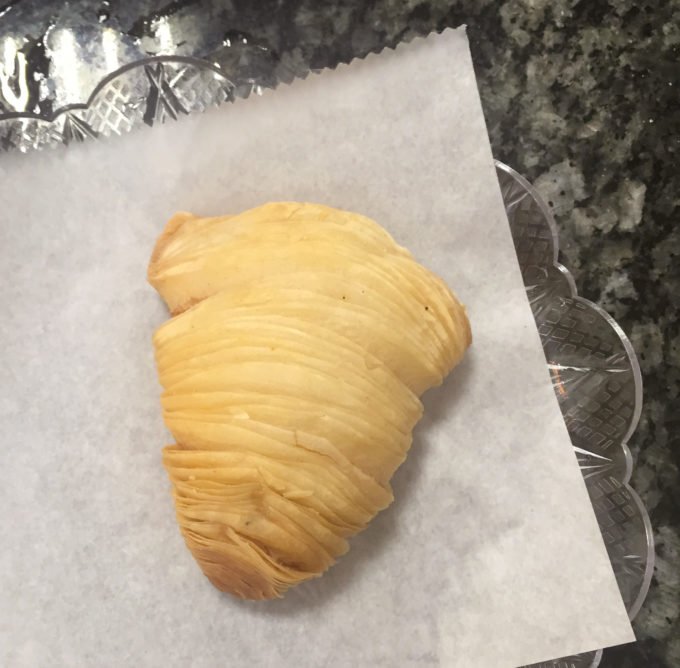

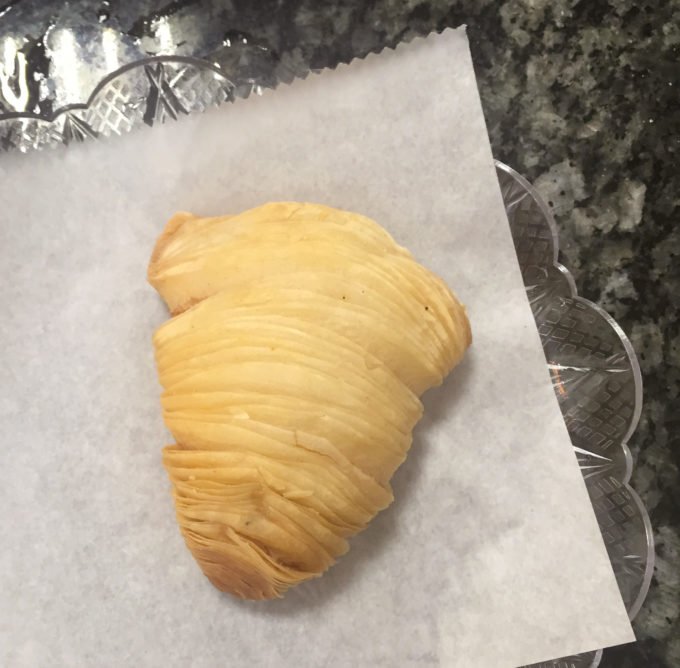

Sfogliatella in Naples

Napoli Centrale, 8 am, I order a sfogliatella from the train station bar even though I’m not hungry. Soon I’ll board the train to Milan then tomorrow fly back to New York. This pastry is the last taste, for now, of the city where I feel most at home.

The barista squints below her visor and asks, “riccia o frolla,” referring to the choice of flaky or smooth pastry wrapped around a soft mound of sweetened ricotta cheese.

“Riccia,” I reply, as though there isn’t really a choice, and her posture softens. Reaching under the counter with a square of wax paper folded against her palm, she tells me that my accent sounds foreign, but she is confused by my very Neapolitan face.

I always have this conversation in Naples. With my dark hair that does whatever it wants and heavy eyelids, only my New York accent betrays me as not a local. Neapolitan friends have picked apart my face to identify the regional mix of conquerors and oppressors: Greek, Spanish, a little French maybe. In America, I’m accused of having “resting bitch face,” but here among citizens whose philosophical musings are informed by the nearby volcano, I belong to them.

“Italo-Americana,” I say with a shrug.

“You chose the riccia, proof of good Neapolitan blood,” she says with approval, passing the sfogliatella across the marble counter. My fingertips press against the paper to feel its heat and hear the pastry crackle, proof of freshness that even in the Naples train station is assured.

Sfogliatelle have been my favorite sweet since childhood, when my grandparents would bring over a string-tied box of them fresh from the Bronx. When I started coming to Naples as an adult and discovered that these were not holiday treats, but what you eat here every single morning, it was like the 6-year old inside of me was told she could indeed have candy for breakfast.

But there are also rules. Like cappuccino, sfogliatelle are not something any Italian would dare consume after a big dinner, though Neapolitans find excuses like the merenda, or afternoon snack, which may come as late as twilight and is best enjoyed while swanning around the Piazza dei Martiri with friends.

Like Parthenope, the siren founder of Naples who died of heartbreak and washed up on the coast, the sfogliatella also arrived from the sea. One origin story, rote but beloved, describes a 16th century nun on the Amalfi coast experimenting with some cooked flour and milk during the dark early hours inside the convent’s kitchen. She formed the pastry to imitate the shape of a monk’s hood hanging along his back, thus inventing the smooth frolla version.

The recipe was made distinctly Neapolitan when a man named Pasquale Pintauro created a flaky shell that reminded of elaborate French pastries still fashionable in Naples, even after Marie Antoinette’s big sister had been deposed as queen. In the window of Pintauro’s pastry shop on the fashionable Via Toledo, the sfogliatelle were upended to resemble seashells, the new Rococo architectural motif in the city ruled by a Spanish Bourbon king.

Almost 200 years later, Pintauro’s pastry shop on the Via Toledo is still in place. Locals gather there for sfogliatelle on Sunday afternoons though legions loyal to “La Sfogliatella Mary” crowd around it in the Galleria Umberto.

Back at the train station bar, I wipe a galaxy of transparent crumbs off my scarf and take one last shot of caffé normale. I’ll creep back into my American skin tomorrow in Milan at the hotel’s continental breakfast.