Call center jobs are providing hope for English-speaking Guatemalans deported from the United States.

GUATEMALA CITY—

At Guatemala City’s air base, William Rene España exits a commercial jet onto the tarmac as part of a group of about 130 migrants deported from the United States in October 2015. He walks single-file into a migrant processing center. He shuffles his feet, trying not to trip over his laceless shoes: Before the flight, officials confiscated the migrants’ shoelaces along with belts or any other personal item that could be used as a weapon against themselves or someone else—a precaution against the desperation some feel upon return.

Immigration officials hand him a brown-bagged lunch and water bottle. He takes his seat along with the other deportees, mainly men except for the front row filled with women. An official welcomes the migrants back with a quick pep-talk that earns him a round of applause.

España’s name blasts over a loudspeaker and he takes his turn at a counter that serves as the deportee version of customs where migrants’ identities are verified. After that, he’s on his own. España has no friends, family, or knowledge of the country he left when he was 14. “I had everything I needed: my own place, a job,” España said of living in Los Angeles for more than four decades. “But I came over here and I don’t have anything.”

Guatemala receives the second-highest number of deportees from the U.S. each year, second to only Mexico. More than 33,000 Guatemalans were deported from the U.S. in 2015, and 55,000 in 2014. In June 2014, a surge of migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras crossed the U.S. border. As many of these legal cases begin to wrap up, thousands will face deportation to their home countries, and many of these deportees will risk migrating again if their socioeconomic situation has not improved and violent conditions persist.

For years, España lived legally in the U.S. as a permanent resident but never took the extra steps to become a U.S. citizen. When he failed to renew his residency, his immigration status changed to undocumented. He never faced any trouble with the law that would call attention to his immigration status and suspects a neighbor reported him to Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

Now in Guatemala, España does have one thing going for him. After decades in the U.S., he speaks fluent English, a desirable skill that could land him a well-paying job in one of Guatemala’s growing number of call centers, a booming industry in Latin America worth billions of dollars. Every day, thousands of Guatemalans speak with customers from the U.S. and Canada to solve internet, cable, or banking issues. In Guatemala, English-speaking call center positions pay double to quadruple times the monthly minimum salary of about $350 with potential raises opportunities to advance.

As a furniture mover in Los Angeles, España made much more than a few hundred dollars a month and grew accustomed to a lifestyle of eating out and watching Netflix, splurges he might not be able to afford on a local salary. In Guatemala, more than 50 percent of the population lives in poverty according to the World Bank.

And the conditions that Guatemalans live in explain the desire to leave: lack of job opportunities, gang-related violence, and limited access to quality education. But deportees with new language skills, often learned through working in the U.S. for years or even decades, have a better chance of improving their situations in their home country.

At the air base, the migrants are all discharged at once, creating havoc outside the processing center as organizations try to catch their attention, offering them a free phone call or a one-night stay in a shelter.

Among those waiting outside the air base, dressed in a sleek gray suit, is entrepreneur and call center recruiter Jose Andres Ordoñez. Ordoñez tries to grab the attention of dozens of deportees as they exit. Some rush to reunite with their families. Others meet their coyotes—migrant smugglers—for round two. This is the cycle Ordoñez hopes to stop.

“These people have been out of the country for a lot of years. Many of them don’t have any friends or any family members and of course they don’t have a job,” said Ordoñez in near-perfect English, although he has never lived or studied outside of Guatemala. “These people need to find a job and get reinstated in society as soon as possible.”

Most migrants rush by, but España lingers. When Ordoñez hears how well España speaks English, he knows finding him a job will be easy.

Ordoñez comes to the air base every day to offer free job training for call center positions in Guatemala through the company he co-founded, Conexion Laboral (Labor Connection). After working as a call center recruiter for years, Ordoñez saw a gap in the skills of potential hires, even those who speak as fluently as España, and call center standards. Bilingual deportees can easily pass an oral exam based on their level of English but often struggle to pass the writing test and formal interview.

Conexion Laboral provides this training for free through a special recruitment effort for returning migrants called Te Conecta (“Connect You”), a program Ordoñez estimates helps 40 deportees find a job each month. Conexion Laboral is a for-profit business, which generates income from call centers that pay for recruitment services. NGOs have a strong presence in Guatemala, but suit-clad Ordoñez represents the private sector, which he considers an untapped resource for solving social issues in Central America.

“It’s very important that companies tackle these social issues in Guatemala. It needs to go beyond social responsibility,” Ordoñez said. “Small and big companies should try to solve a problem in society and find a way to make it sustainable.”

Ordoñez, who has an MBA, confronts this social issue in a business-savvy way. His company offers shared value—a business term for a win-win situation—to both deportees and call centers. Since undocumented migrants in the U.S. often work in the construction, landscaping, or restaurant industries, he suggests these markets could also find an untapped labor force at the air base while also having a positive social impact in Guatemala.

Conexion Laboral cannot solve all of the social issues in Guatemala that often lead to migration. It instead focuses on the niche market of call centers because Ordoñez has years of experience as a recruiter and knows the industry. But these jobs require advanced English language skills, something that can’t be learned in the organization’s two- to three-week training sessions. This limits the number of people Ordoñez can help.

On a cloudy morning, 22-year-old Heidi Molina arrives at the Guatemala City air base after only four days in the U.S., all spent at a detention center in Texas. She left her home in Petén, a Guatemalan province near the border with Belize, because she lost her job when the store she worked for closed. Helping pay for her mother’s medical expenses after a car accident was difficult for Molina.

“Three months without earning anything when you have debt is really difficult,” Molina said. “That’s why I left.”

The hope of finding work in her home country lures Molina to Ordoñez’s booth. But the only English she knows are the numbers one through 10.

“We would like to help all of them, but it’s really hard,” Ordoñez said. “If they learn how to speak English in the United States, it’s really easy for us to help them out.”

I know that the journey is hard, but the situation forces me to go.

Molina graduated high school, which could qualify her for a Spanish-language position at a call center, but Ordoñez can’t guarantee her a job. Molina takes a Conexion Laboral flier, uses her free phone call, and leaves the air base to stay with a family member in Guatemala City.

“If I don’t find work, I will try [to reach the U.S.] again and take the risk,” Molina said. “I know that the journey is hard, but the situation forces me to go.”

España had a similar mentality when he arrived in Guatemala, which feels like a foreign country to him. Having spent more time in the U.S. than Guatemala, even the perilous journey north seemed more bearable than staying in a country where he had nothing.

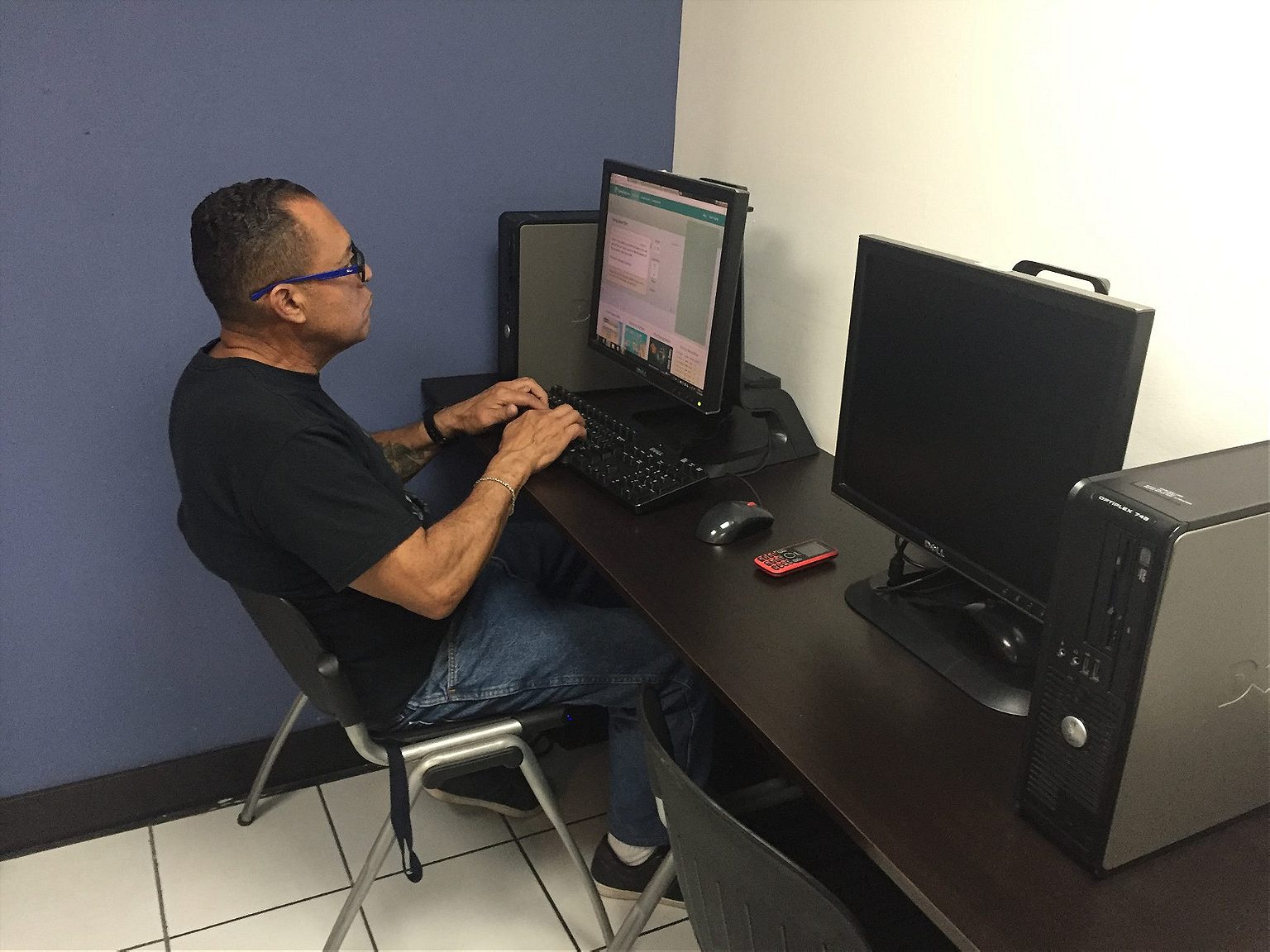

A few weeks after his deportation at the Conexion Laboral office in Guatemala City’s pristine Zone 10 neighborhood, España sits a computer to practice typing so he can pass the entrance exam to work at a call center. The potential job prospect has given him hope: With a stable job, he can imagine staying in Guatemala during the five-year probation period before he can apply to return to the U.S. legally.

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t want to stay here,” España said. “I wanted to go back, but if I get this job, I’m planning to stay.”

Weeks later, España signed his contract to work at a call center and staying in Guatemala became a viable option. For now, for at least one migrant, the cycle is broken.