A look at the grim reality of abusive Koranic schools in Senegal.

For six weeks last year, Mario Cruz photographed the grim reality of abusive Koranic schools in Senegal. But his investigation, which won the first prize for Contemporary Issues from World Press Photo, isn’t about education or religion. It’s about the tens of thousands of talibés, young boys who are exploited, beaten and sometimes even raped by a network of men that hide behind a tradition gone awry. Now, he’s raising funds to create a book that will help raise awareness about the widespread practice. He joined R&K from his home in Lisbon.

Roads & Kingdoms: What is the role of daaras, Koranic schools in Senegal?

Mario Cruz: The daara tradition used to be a good tradition. It was a respected way of teaching. But in the last decade, many daaras were transformed into places of torture. The talibé system is out of control. Nobody knows how many daaras are in Senegal and it’s really difficult to get access to them. The government always tries to do something about them when Senegal celebrates the National Day for Talibés, but nothing gets done. Right now, the proportions are very worrying because more than 30,000 talibés are subject to this kind of treatment in the Dakar region alone.

R&K: So traditionally, daaras were simply meant to be schools.

Cruz: Yes, and traditionally they were good schools. It is true that students would have to beg for one hour every day, but they would keep the money they collected and use it for their education, for their books. What happened was that these false Koranic teachers appeared, and now many students have to beg eight hours a day and are subject to physical abuse. Unfortunately though many parents still believe that the talibé system is still a good one. So they trust these teachers, called marabouts, and they never see their children again. You have to understand that they are poor families who cannot provide an education for their children. When I was researching this story, I realized that the lack of proof was an obstacle to creating change. That’s why I decided to go there and do this work, because collecting information was key to change the mentality of the Senegalese society and to make people understand what’s really going on.

These false teachers were using religion to mask a criminal network

R&K: The project actually started as a story about trafficking. How did it take you to the talibés?

Cruz: I was in Guinea-Bissau in 2009 when I first heard stories about missing children that were being trafficked to Senegal. To be honest, I didn’t feel prepared to dig into this kind of story at the time. After a couple of years documenting issues in my own country, I decided to try and find out what was really going on. I talked to some international NGOs to understand how the trafficking was happening, and that’s when I found out about the talibés. It really caught my attention because it was a story about these men, these false teachers, who were using religion to mask a criminal network.

R&K: Why are marabouts taking children from Guinea-Bissau into Senegal?

Cruz: They are neighboring countries, so it’s easy for them to traffic children into Senegal. But fortunately, things are changing a little bit. For instance, now you cannot leave Bissau, the capital, with a child unless you have the permission of both parents. Some measures have been taken to minimize this reality.

R&K: Are there daaras in Guinea-Bissau?

Cruz: Yes, there are good daaras. This kind of treatment tends to be concentrated in Senegal.

R&K: The access you got is incredible, can you talk about how you managed to get the proof you were looking for?

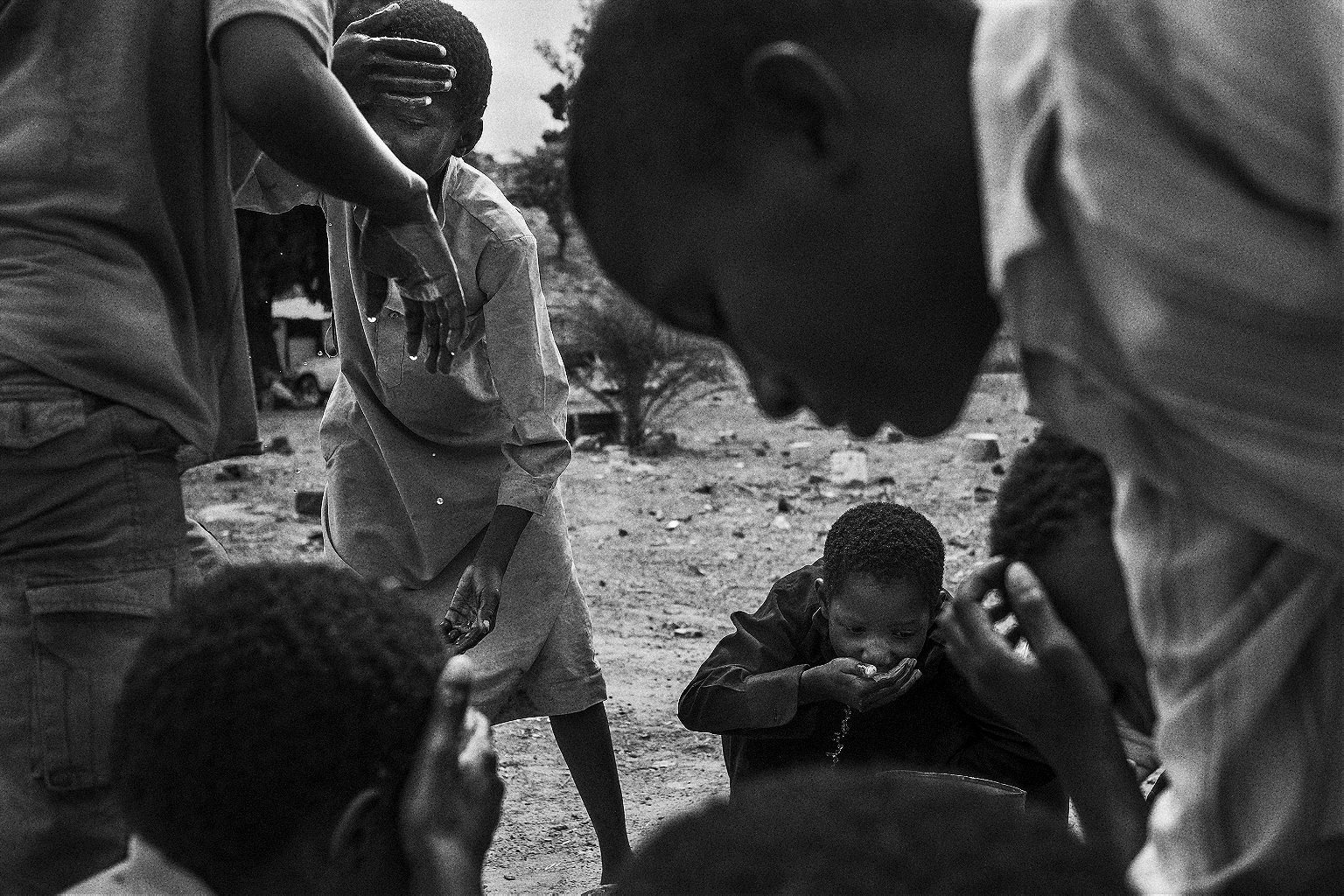

Cruz: That was the hardest part of course. During six months I did a lot of investigating and got in touch with people who could enable some access. I found local NGOs that were working with some of the daaras and one in particular helped me a lot. It was extremely difficult to get inside a daara and to see what was happening. The first time I saw a child being whipped in front of me, I wasn’t prepared for it. But this kind of treatment was so common that they kept doing it. So I just had to take the photo and act normally. It’s a reality that should never exist. I had to keep in my mind what I was doing and why. The marabouts are aware of the crimes they are committing and they know that my camera could damage their business, so it was just a matter of taking some risks and waiting for the right moment.

R&K: How much were you able to talk to the marabouts?

Cruz: Many didn’t want to talk to me, but the ones that did said that they know the talibés have a hard life, but they believe that it’s a good thing for them. They say they are preparing them for a life of work. But what they do instead is they beat the kids, they rape them, and so of course when you are talking to people with this kind of mentality you can’t say what you want to say. The best thing you can do is to do your job and take the photos that will serve as proof, as a testimony to the struggle of the more than 50,000 children in this situation. That was a thought that was always on my mind.

R&K: Why do you think some of the marabouts let you in?

Cruz: I think they saw me as a way to make money. They thought if I took some pictures, maybe some NGO will want to help financially. They only care about money. One of the conditions to get into some of the daaras was that I would only go in in the middle of the night or early in the morning. That way nobody could see me getting in. It gives you an idea of how the system is hidden from view. Some of these daaras are in the middle of nowhere, it’s true, but other daaras are in big cities, in unfinished buildings for example. You would never guess there are 50 children inside, crying for help. One thing I found was that some NGOs were contributing to the problem because they didn’t know which daaras were bad ones. Once they found out of course, they would cut the funding, but they have a big duality to solve because if they stop giving money, then nothing at all goes to the children.

Some of the older talibés become what they hate; they become marabouts

R&K: What happens when the children turn 16?

Cruz: It depends. One of the things that scares me most is that some of the older talibés become what they hate; they become marabouts. In the daaras some of them already control the younger talibés. It’s a very sad cycle. Others just try to run away. Saint Louis, a city up north of Senegal, is known as talibé city because you have so many there who live in the streets.

R&K: Because technically they can run away at any point when they’re out begging.

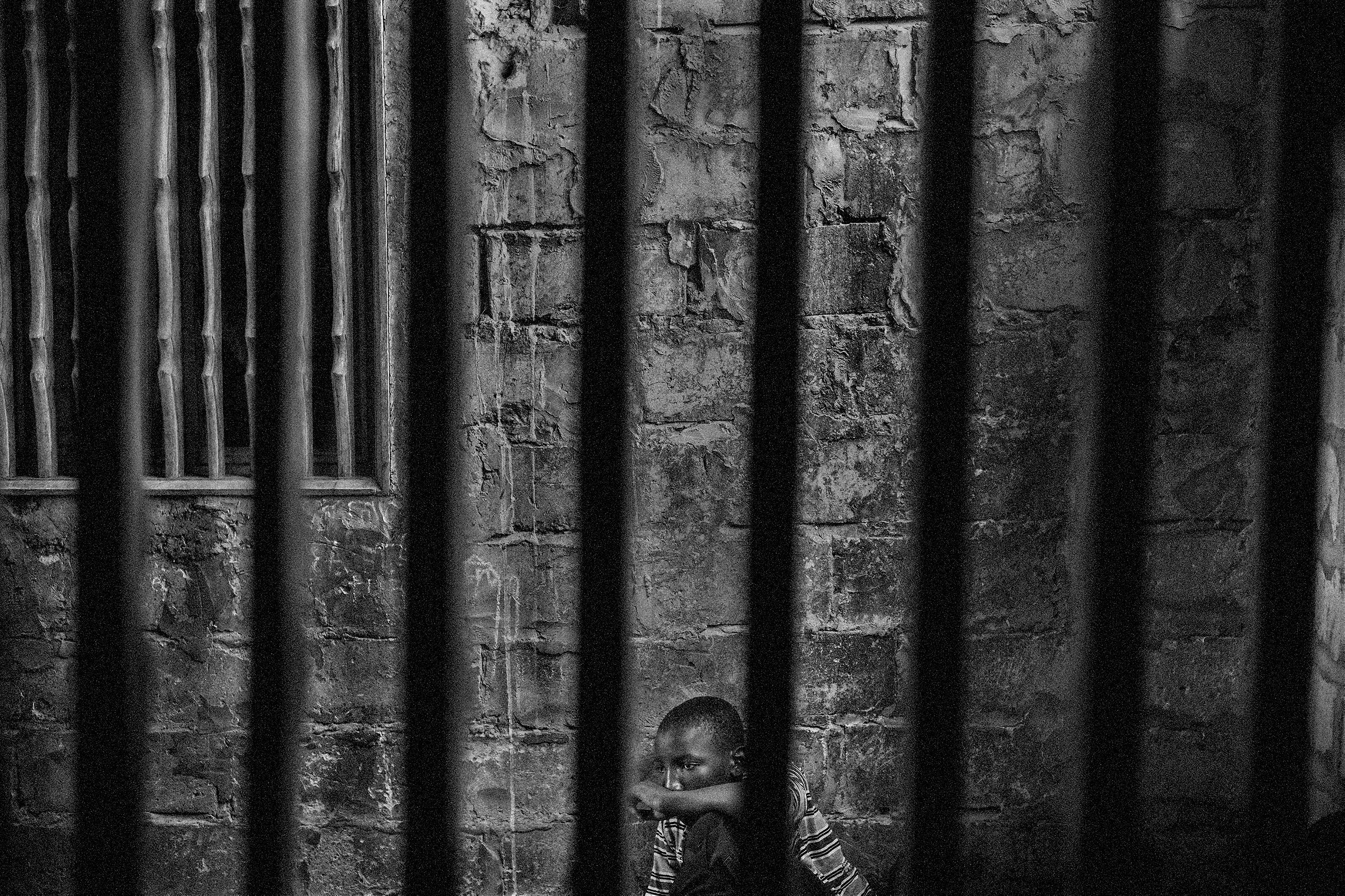

Cruz: Yes. But they are so afraid. It’s really sad because some of the talibés who run away go to the police, and the police sends them back because they don’t care. And if that happens, the punishment will be very hard. Inside the daaras, the children tremble with fear. You are never prepared to see this kind of thing. Many of them don’t even sleep during the night because they are afraid of getting raped so they end up sleeping in the streets.

R&K: It must have been extremely difficult to form a bond with the children you photographed. What were your interactions like?

Cruz: I spoke with a lot of talibés who had run away. Those who are still inside daaras have to follow a code of silence, so they are not allowed to speak with anyone except to ask for money. They are always being watched, if not by the marabout then by an older talibé. It was difficult to talk to them of course, but my fixer who worked with a local NGO knows all about this reality and he works 24/7 with these children so he knows how to talk to them, how to approach them. As for the talibés who ran away, they are well aware of the risks they take. Many of them get caught up in other networks of trafficking. Even after they are rescued, the reintegration process is really, really difficult. They don’t know which country they come from, or who their parents are.

R&K: And for the families, at what point do they realize what is happening?

Cruz: In Guinea-Bissau, when a case of abuse makes it in the local newspapers, parents try to understand what’s happening, they try to find some help. But it’s difficult to find daaras, it’s difficult to find their sons. I think that now, many parents in Senegal try to know where the daara is first, and try to visit it before they allow their sons to go there. But the problem is that most people don’t believe that this old talibé tradition has changed so much. It’s a generation problem. Some of the parents had a good education in a daara themselves, but it was many years ago. The abuse is not everywhere, I realize that, but in many daaras this is happening right now and nobody cares. That was one of the things that really shocked me, the indifference from the Senegalese society. Because if you go to Dakar, it’s really common to see talibés begging in the streets. They are everywhere. And people don’t ask: why are there so many? Why are they begging all day? Why aren’t they studying something? I think it’s so common now that they just don’t see it anymore. But it’s really sad because it’s the future of the country we’re talking about. They are children.

R&K: Your project touches very little on religion. Is religion purely an excuse in this case?

Cruz: Yes, it’s an excuse. And that’s why I don’t want to talk about religion. I don’t want to use religion as an excuse like they do. The true Koranic teachers are the first ones to condemn these conditions. They are not schools, they are places of torture. Nothing to do with religion except that they have to memorize some parts of the Koran, but that’s just something to pass time really. It’s not an education in any way.

What’s absolutely necessary is the proof, and now they have it

R&K: What is the government doing to help?

Cruz: The law that is supposed to regulate daaras is yet to pass in Parliament. There are laws against child abuse of course, but things don’t move. I know the story of a marabout who was brought into court and a talibé was there to testify against him. The marabout stood up and said: if you say anything, I will punish you. He said that in front of the judge, in front of everybody. So the talibé went silent because he was afraid and the marabout walked free. After I won the World Press Photo award, I was surprised to get an email from the Senegalese government. They asked me for permission to use the photos. I was happy to receive the email of course, but I’m certain they can do a lot more than that. But I do understand that if this tradition has strong roots in Senegal, you have address people in a very careful way. One thing that is absolutely necessary is the proof, and now they have it. I sent them the photographs and told them to use them in the best way they could. There is no excuse now.