A Little Rude, a Lot of Fun, and Looking for Excitement

A Little Rude, a Lot of Fun, and Looking for Excitement

Cocktails in Havana

Late in February, when a front of unseasonable coolness blanketed Cuba, I spent a night drinking with the young, good-natured punks of Havana. It was one of those blown-out evenings on the island when the city makes you want to drink your face off, and the backstreets of Vedado were suffused in the kind of light that would flatter jineteras and rumrunners.

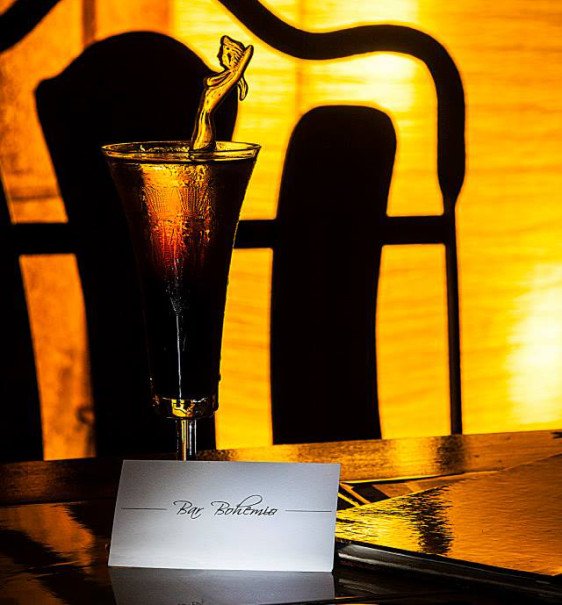

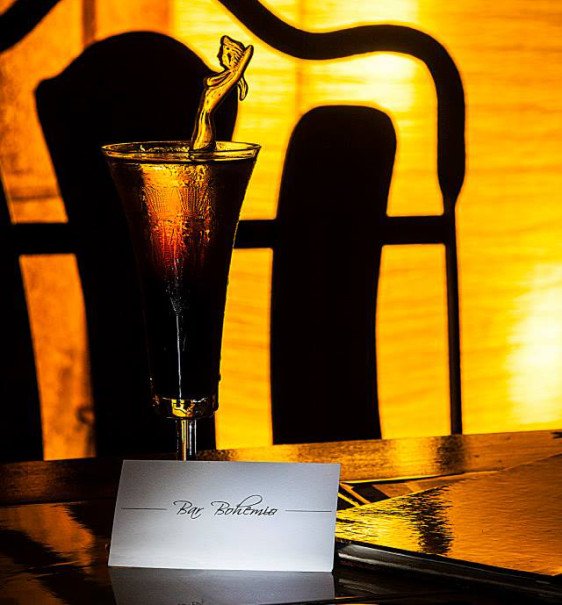

In the cool of the night, I began drinking at Bar Bohemio, a cocktail lounge operating out of a pre-revolutionary mansion in Vedado, the setting for contemporary Havana’s most vibrant nightlife. With a breeze sweeping in from Calle 21, Bar Bohemio felt like a place where ballerinas lounged on daybeds smoking cigarettes and drinking rum, which was apt, since the bar is owned and managed by ex-ballerinas from the Cuban National Ballet Company.

For an hour I drank glasses of calimocho and rum cocktails on the mansion’s quiet terrace, telling a friend of mine from the Bahamas about an email I received from a young Cuban novelist. In the email, the novelist claimed to be writing the “posthumous novel of the [Cuban] Revolution … the Cuban Book of the Dead … [which] must be finished before Fidel Castro dies, so he can officially order my assassination.” We drank to the novelist’s vigor and vainglory. And after a final drink of rum, we went searching for the captivating nightclubs of Vedado—King Bar, La Fábrica de Arte Cubano, and Bertolt Brecht Café Teatro—bars that were turning Havana into a destination for the Western hemisphere’s best parties.

It was well past midnight when we met a few friends at King Bar, and we found it brazenly alive with DJs and poets and sculptors and students. There were suburbanites from Siboney orbiting the dance floor and boho eccentrics from Miramar with cans of Cristal in their hands. Moving around from conversation to conversation I heard grad students talking shit on the Castros; twentysomethings denouncing the government’s minor reforms, alleging that the recent changes were merely a ploy to create a façade of progress for the international media; and filmmakers insisting that a transition to democracy was not ongoing, emphasizing that a transition could only occur when the regime allowed the public to participate in the government.

The young partygoers were a little rude, a lot of fun, and looking for an excitement that couldn’t be found in the uninteresting state-run bars that for decades had devastated Havana’s local soul. They bought cheap rums and vodkas, bent on getting smashed and moving on to the night’s next big thing.

In the likes of Bangkok or South Beach or Panama’s Casco Viejo, my night in Vedado would have seemed like any other Saturday night, but in Havana it was emblematic of a young generation who are reimagining what it means to be Cuban within a new global context. It felt as if the discontented brigades of Cuba’s youth were mobilizing their post-utopian rebellions towards something far more enjoyable than Castroism. And what that meant to me on that night in late February was that the Habaneros were throwing together a breathtaking party.